by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 24, 2023 |

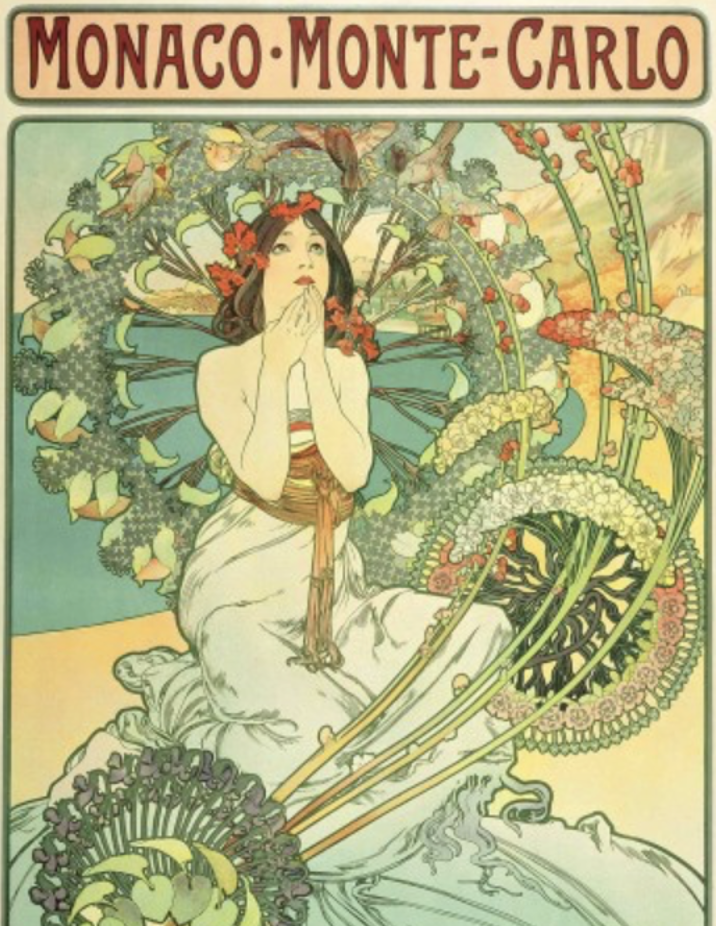

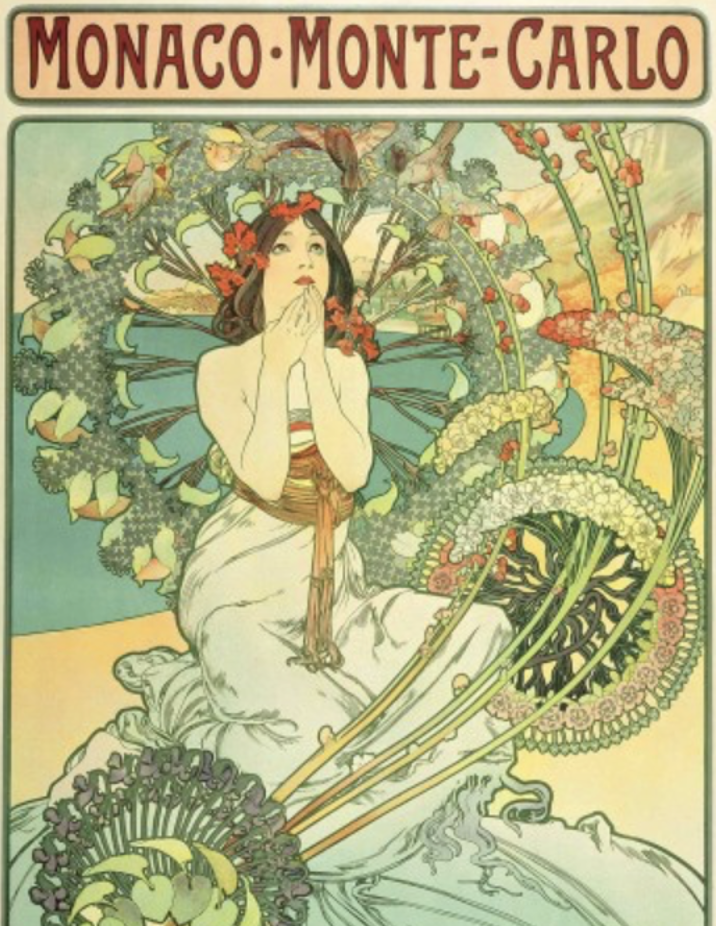

Art Nouveau fans rejoice: July 24th is the late Alphonse Mucha’s birthday. This year’s anniversary comes with a bit less fanfare than his 150th in 2010, when Google created a doodle on the artist’s behalf.

But even without a doodle from Google, Mucha’s legacy continues to influence art and artists around the world. One aspect of his enduring legacy is how his work influenced the rise of celebrity art. This phenomenon has been popping up more and more frequently in American culture, and no one (not even celebrities themselves) are immune from the draw of star power.

Modern Celebrities Embrace Art

No longer playing the role of pirate, actor Johnny Depp has swapped his sword for a paintbrush in real-life. It seems to have been a sound business move. The actor made a staggering $3.6 million selling works from his first “Friends & Heroes” art collection in 2022. His second, entitled “Friends & Heroes II” was released in February. It is comprised of four portraits of artists that have inspired Depp throughout his life: Bob Marley, Health Ledger, River Phoenix, and Hunter S. Thompson. An unbelievable answer to the classic “Dream guests at a dinner party?” question, if ever one existed. Almost already entirely sold out – all that remains on the Castle Fine Art website is a pack of all four prints, priced at a swashbuckling $20,416.67.

Depp’s foray into celebrity art highlights modern culture’s fascination with all-things celebrity. Are Depp’s works prized due to his creative talent as an artist? Or are the pieces selling because they are exclusively of famous celebrities? Or, possibly, Depp is able to sell out faster than Taylor Swift tickets because he, himself, is a celebrity? Which points to the threshold question: when did artists begin to feature celebrities in art? Many art historians look no further than the incredibly gifted Alphonse Mucha, who skyrocketed his own career to greater heights through his collaboration with a famous actress.

Rise of Celebrity Art

“If you have to explain to someone you’re famous, then you’re technically not that famous.”- David Spade.

The beauty of Alphonse Mucha‘s work stems from his deep passion as an artist. Many artists are known for having a lot of gusto, but Mucha really takes the cake. He was master of the Art Nouveau style of art, so masterful in fact that many credit his career for influencing major tenants of the age – politics, religion, philosophy, and – of all things – the career of one very famous actress named Sarah Bernhardt.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘La Plume’ magazine (1897). Image via muchafoundation.org.

Before we get to Sarah, a little more about our man Mucha. He was born on July 24, 1860, in a quiet town in Moravia. In his youth, Mucha was – in his own words – “preoccupied with observing.” This tendency to notice things around him manifested in a profound artistic talent. Young Mucha could be found making sketches and drawings for friends, family, and fellow townsfolk. His drawings were so prodigious that he collected quite a few fans, even in his early days. One fan was the town’s shopkeeper, who often slipped Mucha free sheets of a paper – a luxury of the day – in order for him to make his creations.

As Mucha grew older, his artistic talent also matured. When he was 18, he was ready to apply to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Unfortunately, he was rejected. The admissions office even went as far to suggest he take up a different, “less artistic” career. I’m not sure what they had in mind (medical school?), but fortunately for us, Mucha was not discouraged for long. He decided to simply carry on and continued to make art in whatever way he could.

A year later, Mucha had a bit of luck – an opportunity arose for an artist to work with a Vienna newspaper making advertisements. The pay was pitiful, and Vienna is freezing cold in winter. However, Mucha forged ahead, desperate to create. He applied, scored the gig, and packed his bags for his journey to the big city.

This was a turning point in Mucha’s development as an artist. He spent two years in Vienna, creating advertisements for the paper by day and taking art classes by night. What this did was cement in him a love for creating artwork that was accessible to the average, everyday person. He thrived on creating beauty in pamphlets, posters, and advertisements that most companies and institutions did not have the time or talent to make elaborate. We can start to see, from this period, the development of certain curvature in his lines, and repetition of old world-inspired motifs come up again and again in works that would inevitably become a part of an ordinary person’s daily life.

Mucha retained this love of creating beautiful and accessible work, while still seeking to enhance his skill as an artist through more formal training. Eventually, he applied to – and was accepted to enroll in – the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in September of 1885. This provided Mucha with formal artistic skills, though it is important to note that Mucha is still believed to be largely self-taught as an artist (which could also mean that he ignored much of what was taught in school). From Munich, he made his way to Paris: the art capital of the world at the time.

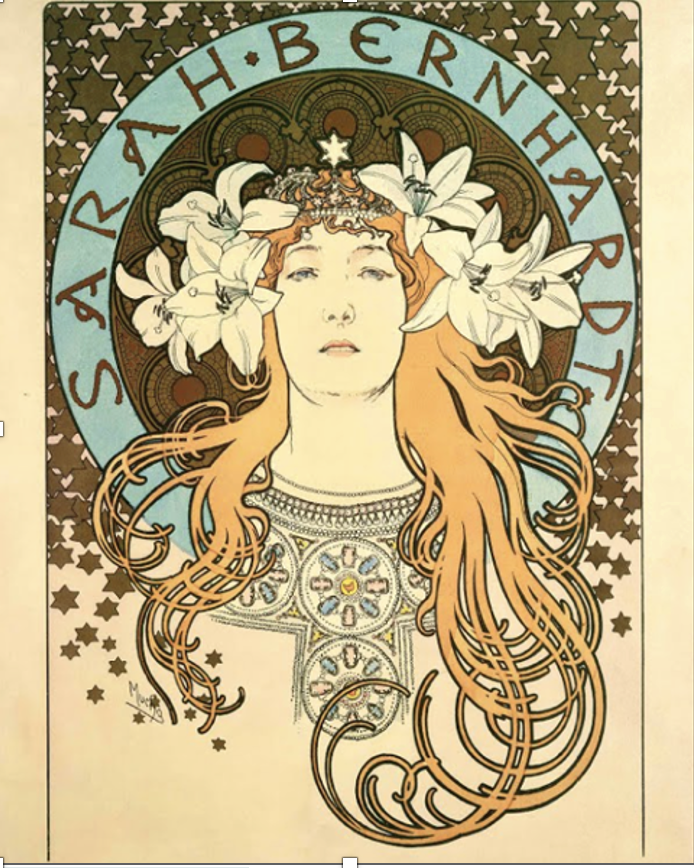

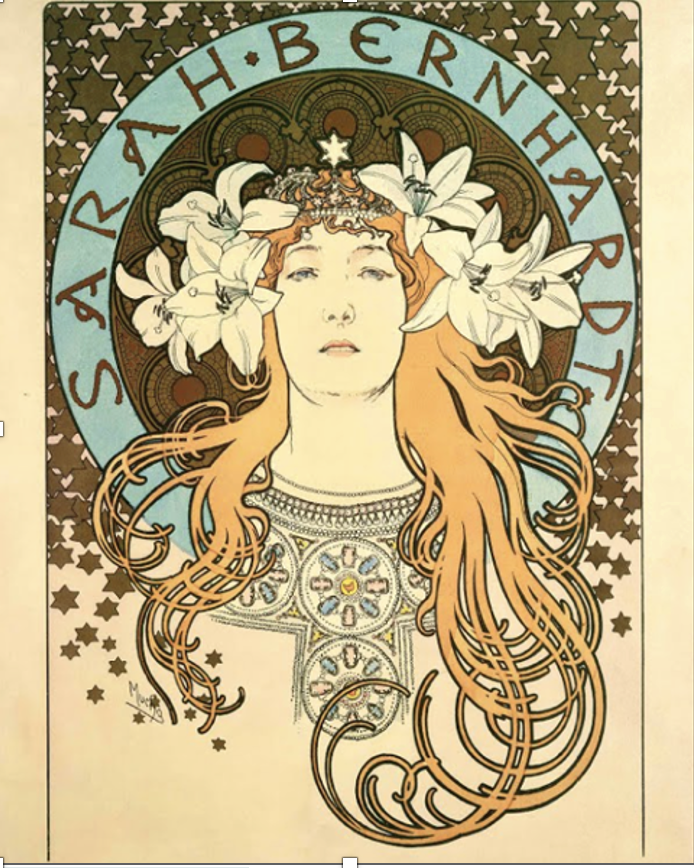

In the City of Lights, he established himself as a “reliable” illustrator (as noted by his biographers). The Paris theater scene is where the lives of Mucha and the phenom Sarah Bernhardt intersect. Sarah Bernhardt is often touted as the original “true superstar.” This is before the current fame-cycle of Hollywood starlets, who now can be seen as a dime a dozen, splashed across the covers of People magazine.

Sarah Bernhardt was the real-deal – a woman with the poise, charisma, and gumption to make a name for herself as an actress against the backdrop of a politically tumultuous city. Not only is she remembered as a strikingly impactful actress, known for her talent, she is also regarded as the first superstar known to personally exploit her own image and likeness for economic gain, and to raise her own fame. This is an important piece of the puzzle of a topic referred to as “publicity,” which we’ll address later.

Mucha began working with Bernhardt in December 1894, in a serendipitous sort of meeting that can only be attributed to fate. Bernhardt’s play, Gismonda, was set to open on January 4th, 1895. On December 26th, 1894 – just a few short days before opening night – the starlet decided that her show needed a new poster to publicize the play. Something dazzling. Something that would leave Paris speechless.

She turned to the manager of a Parisian printing firm for a new poster, pronto. Given the short notice, and the fact that Bernhardt approached the firm in the middle of the Christmas break, Maurice was short on options for the commission. In desperation, he turned to Mucha – truly the only option at hand – and begged him to take on the job. Ever the flexible type, Mucha agreed. And, in doing so, a true collaboration between two legendary artists was born.

The success of Mucha and Bernhardt’s eventual career-long collaboration is likely because the two saw eye-to-eye on Sarah’s talent.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ’Gismonda’ (1894). Image via muchafoundation.org.

In other words, Mucha was a fan. In creating the poster for Gismonda, he relied on his personal knowledge of the play itself, as well as his fascination with how Bernhardt depicted the title role. The result? A stunningly ethereal piece that focused the viewer of the poster on the actress herself, rather than on fussy knickknacks in the background. The poster was truly a spotlight on Sarah, in all her glory – and Sarah loved it.

Thus, the two kicked off a mutually beneficial partnership. Bernhardt became Mucha’s artistic muse and mentor in the industry. They also became very good friends. Each seemed impressed by the other’s commitment to creativity, and fervent refusal to be fenced in by artistic norms of the day. Sarah, for her part, pushed the boundaries of Parisian theater by lobbying for politically impactful roles. Mucha, on his end, blazed a trail as a high-end artist for the lower strata of society.

Much of the work Mucha did for Sarah was accessible to the everyday Parisian, because her giant posters were displayed on the street. And, he created many posters of Bernhardt in her various roles throughout the remainder of her career. Because Mucha continued to make Bernhardt the star of each new poster, his work served to elevate her career to even greater heights. In this way, Bernhardt was able to exploit her own image and likeness to increase her status as a public figure – and was one of the first known celebrities to ever do so.

The upside for Mucha was that, because of his work that featured Sarah, he became higher-in-demand as an artist for other jobs. Mucha became more famous and earned more money because he painted someone famous.

Collaboration v. Exploitation

Mucha’s portrayals of Sarah Bernhardt in his artwork were clearly a collaboration. But, using a celebrity’s image in a work of art does bring forth a question: when can an artist legally make use of a person’s image or likeness in a work of art, if use of that image increases the economic value of the work itself?

Modern Legal Framework & Application

To answer this question, two rights come into play. Both come from state, rather than federal law, and are mostly understood through case law.

The first right is called the right of privacy. This means is that private people have the right to prevent the public disclosure of their name and likeness by others. For example, if a company started using a private person’s face as the logo for a brand of salad dressing, that person could bring an action against that company claiming the right of privacy.

The second right, which sounds similar, but functions very differently, is called the right of publicity. That right means that a person has the right to exploit her own image and likeness for her own economic gain. Using the salad dressing example, this is why “Newman’s Own” salad dressing uses his face on the label. His company profits from the use of his public image on its products. The right belongs to Newman’s heirs, because the value of his image is the fruit of his own hard work as a famous actor. (Confusingly, what is referred to as the right of privacy in New York is, in fact, the right of publicity).

Sometimes, the aforementioned rules change if, instead of, as in the example, an advertiser using the celebrity’s image, the person using the celebrity’s image is an artist creating a work of art.

Some courts have held that any work created by an artist, even if it uses a celebrity’s image, is a form of free expression. The First Amendment protects free speech. Included in the many categories of free speech is art – it’s speech, even if it doesn’t make noise.

Courts that have broadly interpreted the First Amendment free speech protection in cases where an artist uses a celebrity’s image in their art have generally permitted it. According to these courts, if artist’s use of the celebrity image is a form of free speech, it is allowed. However, the application of this principle is not as straightforward as it might appear. While some courts have given artists broad discretion under the First Amendment to use celebrities in their works, other courts have sided with celebrity defendants, under the theory that the artist’s work violates the celebrity’s right of publicity.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 27, 2023 |

We are thrilled to announce the newest publication from associate Maria T. Cannon. Her latest article, “The Need for Speed: Why Recovery of Missing Art Needs an Upgrade,” was published in the ABA’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Newsletter, Spring 2023 Edition.

The Dutch Room with empty frame at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, site of the most notorious art theft in modern history (2016). Image via

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo Credit: Sean Dungan.

The piece discusses a new take on art crime and looting. She highlights how recovering artwork is a race against time. Art, once stolen, is uniquely difficult to find. Moreover, because stolen art is often delicate, it is subject to physical deterioration. Legal channels to recover artwork often slow down the process. Another issue can come from law enforcement. To recover major stolen works of art, the U.S. often relies on FBI agencies that lack crucial insider knowledge of local crime organizations. She acknowledges these difficulties, an offers creative solutions.

Want to read Maria’s article? Contact the ABA Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee for a full copy of this season’s great newsletter.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 12, 2023 |

Our client, Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, with his work “Point of Infinity” in San Francisco. Image via Jessica Chou/The New York Times.

Our firm is proud to announce the public art unveiling of the newest sculpture installation from our esteemed client Hiroshi Sugimoto. Entitled Point of Infinity, Sugimoto’s breathtaking sculpture stands as contemplative sentinel over the San Francisco Bay. The stunning work – intended to draw the eye upwards to an indefinite point – is 69-feet of stainless steel construction. Its very physicality relies on Sugimoto’s precise artistic eye and meticulous engineering skills. The sculpture is 23-feet at its base, yet less than one inch across at its top. To construct such a gravify-defying sculpture, while still maintaining the optical illusion that the two points will (eventually, even if only in the viewer’s minds’ eye) meet, reveals the genius of Sugimoto as an artistic force. It is truly an honor to work with him and represent his work.

Sugimoto began this project in 2017, and our firm has been at his side to protect his artistic and intellectual property in the work. Sugimoto won an open call for artists in order to produce the piece. The Treasure Island Art Program selected his work from an astonishing pool of 495 talented artists.

Manhattan Apartment designed by Hiroshi Sugimoto. Image via Anthony Cotsifas/New York Times.

Our firm is thrilled to call attention to the incredible work and expansive lexicon of Sugimoto. His success across multiple mediums speaks to his innate talent, pure vision, and clear artistic voice. Sugimoto is continually producing new, fresh work and drawing upon past experiences to refine and hone his talent.

In 2019, Sugimoto was featured in The New York Times for designing one of T’s Best Interiors of 2019. The ethereal space included a bathroom that is notably devoid of boxes or clutter of any kind. The cedar ceiling abuts Towada stone walls. Drawing from his heritage, Sugimoto even incorporated salved stones from a now-defunct Kyoto tram station to lay under the cypress tub.

Our client Hiroshi Sugimoto’s collaboration with luxury fragrance house Diptyque, entitled Fragrance of Infinity. Imaga via Diptyque.

In 2021, Sugimoto joined a host of other prominent artists to participate in French cosmetics brand Diptyqe’s limited edition perfume bottles to celebrate the fragrance house’s 60th anniversary. The finished product was inspired by Sugimoto’s childhood memories of seeing the ocean for the first time. Drawing inspiration from the Japanese province of Kankitsuzan, the completed piece evokes an exploration between man and nature. Read more about the collection here.

Moving into 2022, Sugimoto continued to leap across mediums and grow as one of strongest artistic voices of the modern age. In 2022, Sugimoto broke ground on another major installation – a highly-anticipated sculpture garden gracing the Smithsonian Institution. Prominent artists Jeff Koons and Laurie Anderson were in attendance for the ceremony, as was none other than First Lady Jill Biden. The presence of these esteemed guests should come as no surprise. Sugimoto is a superbly talented artist, photographer, architect, and visionary. It is a true honor and privilege to call him a long-time client and for Amineddoleh & Associates to have represented his legal needs for so many valuable art projects, including the above-referenced works.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 22, 2023 |

Anyone who has been a student knows that the fastest way to capture someone’s attention in a noisy cafeteria is to start a food fight. Last summer and fall, something similar happened in the art world, as museums became the backdrop for messy protests. Now, after a short repose, the culprits are at it again. This time, the action is taking place in Italy, with the most recent attack on art having occurred on March 17th in Florence.

Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy. Image via JoJan through Wikimedia Commons.

Wait, What’s Going On?

The targets are priceless pieces of art and cultural heritage. The culprits are climate activists from several distinct groups with the same singular message: pay attention to climate change. The settings are (formerly) peaceful, as in this last attack in Florence.

In Florence, climate activists disrupted an ordinary day by spraying paint over the outer walls of Palazzo Vecchio. That attack on cultural heritage comes on the heels of the destructive actions taken against artwork in museums around the globe. Soup, cake, ink, and even super glue have been haphazardly applied to the most famous works of art in museums’ prized collections within the past year.

Many of these attacks occurred last summer and fall. Then, around the New Year, there was a brief repose. Art world insiders were optimistic that this trend would stop entirely. Time Magazine reported earlier this year that one major group, Extinction Rebellion, had announced a shift away from flashy civil resistance tactics to gain support for their cause. Instead, the group stated their plan to devote energy to large-scale protests that do not break the law. If other climate change groups followed suit, this would mean a dramatic departure from the ink-splattering and soup-slinging tactics directed at fragile pieces of art and cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, a change in tactics does not seem to be the cards. Not only was the fear that these attacks would continue realized by the recent protest in Italy, a quick check-in with the notorious Just Stop Oil climate activist group – of art attack fame – confirmed their general intention to carry on with the practices of last year. The group, in response to Extinction Rebellion’s statement, promised to “escalate” their actions of civil resistance and public disruption. The group even threatened to begin slashing famous paintings – yikes!

First Rule of Fight Climate-Change Club: Talk as Much as You Can About Fight Climate-Change Club

Van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. On view at The National Gallery, London.

The purpose of these art attacks is to get people talking. One recent attack last November was from a group called Last Generation Austria, in protest of Austria’s reliance on fossil fuels. Two activists threw black liquid (presumably representing oil) at the delicate 1915 painting Death and Life (1915) by Gustav Klimt. One activist was promptly removed from the scene by security. The second succeeded in gluing his hand to the glass panel encasing Klimt’s valuable painting. This gluing action was a serious risk both to the safety of the dizzyingly priceless piece of cultural heritage behind the glass, and to the climate activist’s personal hand health. It seems the activist cared very much for climate change, but very little for his hand.

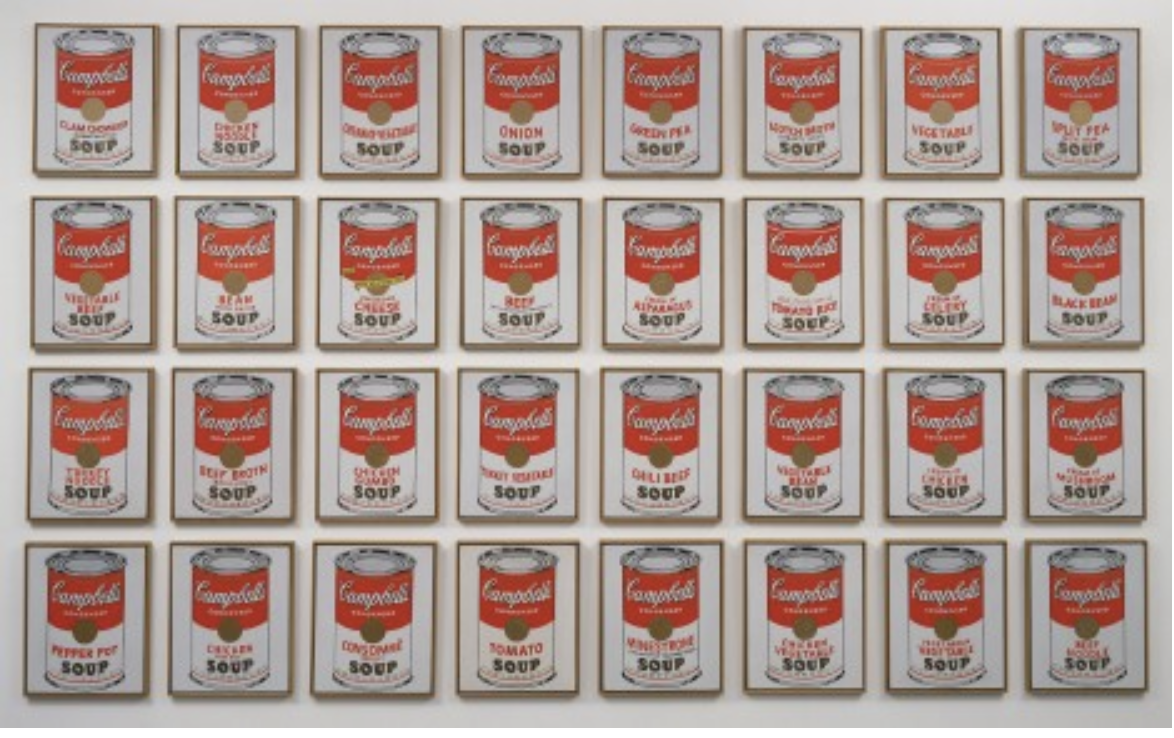

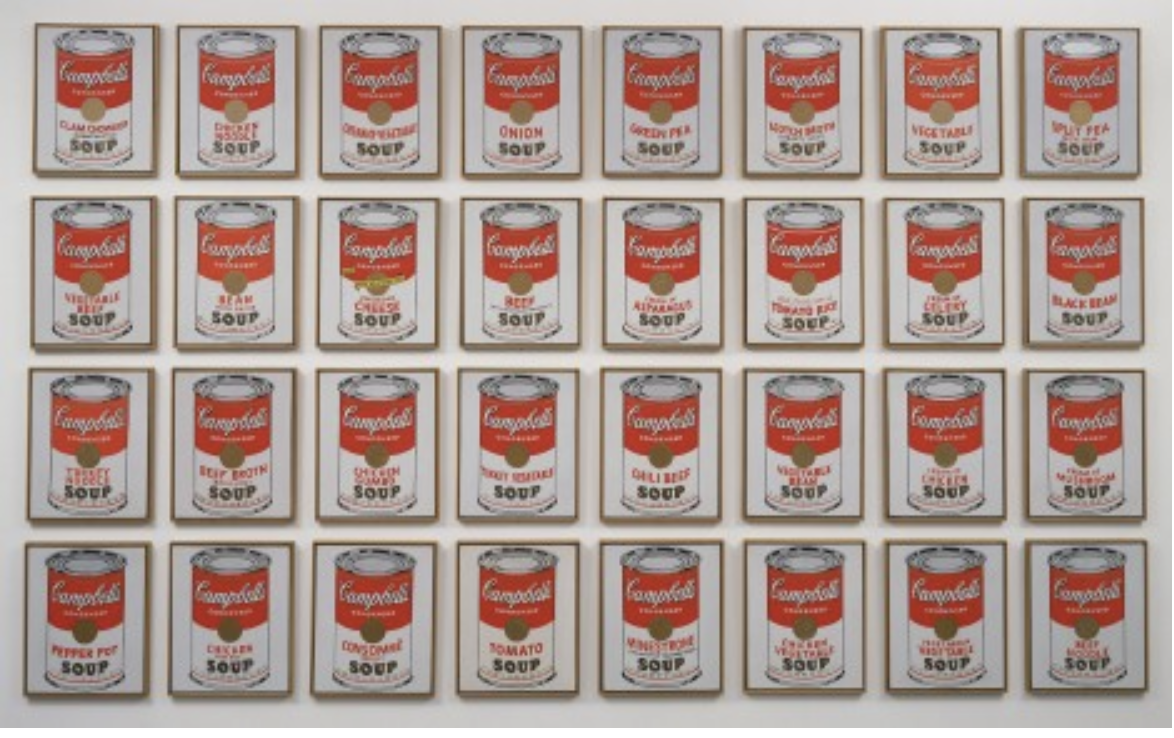

The above attack was likely inspired by the group that finds itself the major instigator of this global operation. Just Stop Oil (the O.G. art attack tribe of climate protestors) has been at this game since earlier last summer. The most publicized attack by Just Stop Oil featured a pair of activists throwing tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers. During the attack, two 21-year old activists leaped over the velvet ropes stationed in front of Van Gogh’s painting, removed their jackets to reveal matching “Just Stop Oil” t-shirts, and slapped soup onto the painting. Not only is this display of wanton disregard shocking, but it boggles the mind that the target of the soup-based attack was not a Warhol work!

The attack seems to be connected to another recent event of art vandalism that took place that same month in the National Gallery of Australia. That incident involved members of a different group, Stop Fossil Fuels, scribbling ink on Andy Warhol’s screen prints of soup cans. The similarities cannot be ignored, as they follow a similar attention-mongering logic. However, why Just Stop Oil applied soup to varnish, while Stop Fossil Fuels applied varnish to soup, is a total mystery.

The above examples are merely a sampling of the demonstrative protests that have occurred in major museums since the beginning of the summer. They all follow a similar pattern: either a defacing with food or liquid, or protestors gluing themselves to a frame or glass. The latter is an imitation of the form of “locking” protest, in which activists will chain themselves to a stationary object to make it more difficult to be removed by authorities.

Fortunately, it seems that the works involved were unharmed, since they are protected by glass and other protective casings applied by art conservators. In the case of Just Stop Oil and Sunflowers, it was publicly known that the tomato soup would not damage the painting (according to Emma Brown, the founder of Just Stop Oil). Brown asserts that her group’s motivation has never been to destroy art. Rather, it is to engage in a conversation about why damaged artwork incites rage, while news reports of climate change do not.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Image via AP News.

This is not an illogical question, when framed in the proper context. However, when news reports of food being thrown in national galleries are splayed across individual computer screens, the intentions of Just Stop Oil’s efforts are lost in the absurdity of the situation. Food throwing, it seems, is better left in the era of summer camp hijinks.

It seems that the message may have been lost on the public, and that the method of protest may be too radical. In this way, they may be ostracizing potential friends of the cause by turning them off with their flamboyant and messy displays of passion. This would result in the activists seeming to be more like vandals to be avoided, rather than potential friends to be admired.

In fact, these stunts create animosity with museums and the public. By using art to stage protests, museums are now heightening security, leading to a less personal experience at art institutions. Increased security measures and the temporary removal and cleaning of artworks is an added expense for our public institutions. After significant drops in revenue during COVID pandemic, the last thing museums need is to waste funds cleaning up after these messy stunts.

Iconoclasm and Art Vandalism

Just Stop Oil’s flashy protests are not the first instances of art vandalism, nor will they be the last, as art vandalism has a long history of activists using destruction to send a political message. Dr. Stacy Boldrick, author of Iconoclasm and the Museum, explores the history of iconoclasm, which she defines as “image-breaking.” Public perception of iconoclasm influences how the broken image enters a culture’s consciousness, which can result in an almost secondary, separate work of art that begins a life of its own. Even if the piece is restored to its original glory, photos of the work in its defaced form become famous symbols of a particular political movement.

An example of this is none other than the famous Rokeby Venus, and its slashing by suffragette Mary Richardson in protest of the oppression of women. Readers of the blog will recall our firm’s piece on work (for a refresher, click here), and its haunted provenance. The history of the work influenced newspapers of the time to claim Richardson was acting from psychosis induced by Venus’s beauty. Boldrick, on the other hand, makes an argument for Richardson as a legitimate defender of the rights of women, though one who took her message to the extreme. Setting Richardson’s mental state aside, the images of the slashed Rokeby Venus are nearly as impactful as the restored version. The photos of the slashed painting draw the eye toward the ostentatiousness of Venus’s body, framing the voluptuous woman in a context of forced femininity.

The slashed Rokeby Venus. Image via artinsociety.com

Another example of a defaced work sparking its own conversation occurred following artist Tony Shafrazi’s 1974 defacing of Picasso’s Guernica. Shafrazi strode up to Guernica and spray painted “KILL LIES ALL” across the piece, in protest of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Fortunately, the painting itself was protected by a heavy coat of varnish. Museum curators were able to quickly clean off the spray paint. Even so, the photos of the defaced work, prior to the cleaning, became political messages. Moreover, Shafrazi himself went on to use the fame garnered by his demonstration to fuel his own artistic career. He is currently still doing well as a successful gallery owner and art dealer in New York.

Shafrazi proves that images of defaced art can send a cultural message by spreading the agenda of the activist who vandalized the work. However, sending a message does not always result in actual change on an individual level. If activists truly desire to change public behavior, there are more effective ways to evoke such action – ways that do not involve defacing fragile, famous works of art. Additionally, museums themselves can take action to promote sustainable, collaborative conversations with activist groups, all while keeping the art safe (and away from tomato soup).

Special Exhibitions

The North Carolina Museum of Art put on an exhibition this past summer that would have appealed to Just Stop Oil’s team of activists, because the show featured artists whose work brings attention to the dangers of climate change. The show, Fault Lines: Art and the Environment, featured artists such as Willie Cole, who did a site-specific installation of a chandelier made entirely out of single-use plastic water bottles. Another artist, Richard Mosse, exhibited works that used infrared technology applied to aerial photographs of geological locations to raise awareness of issues such as deforestation. Featured works of Mosse included: Aluminum Refinery, Paraguay; Burnt Pantanal III; Juvencio’s Mine, Paraguay; and Subterranean Fire, Pantanal.

Richard Mosse, Girl From the North Country, 2015. Image via artsy.net.

Also shown in the exhibit were works created by sisters Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim, whose whimsical crocheted coral reef draws attention to the devastating impact of climate change and plastic trash on the lives of coal reefs. The sisters also did an installation called The Midden, which was constructed of the trash the duo collected walking on the beach over a period of four years.

This writer, a visitor of the exhibit, was particularly influenced by the Wertheim’s trash collecting piece and by the plastic bottle chandelier by Cole. As the writer herself was sipping from a single-use plastic bottle, she was made aware of her personal impact on climate change as a visitor of the exhibit. The writer immediately vowed to use reusable water bottles from that moment on. She joined others on the way out of the exhibit in pledging to reduce all single-use plastics by dropping a recyclable token into the glass canister provided by the front door.

The purpose of the exhibit was to use video, photography, sculpture, and mixed-media works to offer new perspectives in addressing urgent environmental issues. The exhibit highlighted the consequences of inaction, while providing opportunities for patrons to take their own steps towards sustainable environmental stewardship and restoration. This resulted in a celebration of the creation, rather than the destruction, of art in its fullest capacity to send a message to society. By focusing on creation, patrons were encouraged to be part of a constructive solution to climate change alongside the artist activists who produced the pieces shown in the gallery. When asked how about the public response to the exhibit, Virginia Ambar, Assistant Director of Ticketing and Visitor Experience at NCMA said this: “Many people commented on how important it is to highlight our collective roles in affecting our environment and that the exhibit did that in ways that were both startling and beautiful.”

Museum Joint Statement

One way museums have been guarding themselves against art attacks has been to increase private security methods on museum grounds. These increased security measures have taken the form of additional guards, added cameras, and metal detectors – which all come with their own costs. Increasing security is a pricey endeavor, and not one that most museums have the budget for, particularly coming out of the hardships museums faced during the pandemic lockdowns.

Another option is for major public institutions to continue releasing joint statements concerning these matters. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) released a statement signed by over 90 museum leaders. Included among the high-profile supporters were figures from the Prado, the Guggenheim, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The statement explains the precariousness of the art being targeted, and highlights the vulnerability of delicate works of art, even when they are protected behind glass. While the statement does not address the issues raised by climate change, it does draw a clear line in the sand to draw attention to the riskiness of targeting these fragile and irreplaceable treasures.

Climate protestors march through city centers, causing traffic delays. Image via juststopoil.org

It is a showing of museum solidarity against protests. Its impact is yet to be seen, but there is hope that the statement will have an impact on protestors. The breadth of the ICOM statement, combined with the released statement by the American Association of Museum Directors on the same topic, last year, might speak to the protestors in a way that results in fewer art attacks. Taken together, the statements serve to highlight the damage caused by targeting art and the vulnerability of objects used in protests, without casting judgment on the protestors’ message. Rather, these statements encourage compassion on a global scale. Being good stewards of art and advocates for the environment both involve recognizing ways to nurture our shared humanity.

Conclusion

Collaboration is a better way forward than flashy protests. The lifespan of a shocking protest is only that of the flash-in-the-pan clickbait headline. As such, the political messaging of Just Stop Oil continues to be lost in the noise of the internet. Moreover, the fact of the matter is that throwing food at art to send a message is not sustainable. The shock value wears off eventually. It also wastes food and paint, not to mention the environmental impact of cleaning up the destruction. Remember the Italian climate activists’ recent activity in Florence? Ironically, even their spray painting seems to have caused more environmental harm than good. Nardella, the mayor of Florence, reported that “more than 5,000 liters of water were consumed to clean up Palazzo Vecchio” following the destructive protest.

Art, on the other hand, is constantly reinventing itself in sustainable ways that are fresh and exciting. Because of art’s evolving nature, activists who choose to work with artists and museums in a constructive, rather than a destructive, way, have the potential to sustainably effect real social change.

It’s a framework for elevated discourse. It smells like progress, not tomato soup.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 13, 2023 |

At 6:30pm on Monday evening, April 15, 2019, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris began to burn.

Notre-Dame Cathedral’s spire on fire on April 15, 2019. Image courtesy Antoninnnnn via Wikimedia Commons.

Considered a jewel of Gothic architecture, the inferno began in what has been referred to as the “forest” of wooden beams inside the Cathedral’s roof. These beams caught fire and collapsed – a big issue, because the wooden forest of beams had provided much-needed support for the entire structure. After the beams disintegrated, the Cathedral crumbled. Onlookers, who yearned for the building to be saved from disaster, lost hope. As the Cathedral sank, smoke and dust rose to overtake the horizon.

Four years later, the darkness has cleared and hope abounds. The shock felt by millions around the world has softened, and the Cathedral’s on-going renovation is chugging along like the Little Engine that Could.

The inner framework of Notre-Dame, just months before the 2019 fire. Image courtesy SamuelPrr14 via Wikimedia Commons.

However, this chugging along is certainly that – a slow, steady pace. Originally, an anticipated re-opening date was set for April 19, 2024. This date would have been ideal as it is the fifth anniversary of the fire. Yet, due to delays, that plan has been scrapped. Several things have gotten in the way of the original timeframe (two major ones being a global pandemic and the outbreak of war in Ukraine).

Renovators, seeing that the finish line was not quite in sight to make that deadline, made adjustments. “Plan B” was to have the project finished by the summer of 2024. This would have meant that the reveal of refreshed cathedral would coincide with Paris’s highly anticipated 2024 Summer Olympic Games. Unfortunately, that plan has also been scrapped and tossed in the rubble. The newest official re-opening goal date is set for December 2024.

However, it is important to understand what “re-opening” entails. December 2024 is unlikely to mark the completion of all necessary renovations. Total completion by this date is not the goal; rather, it is to have the space ready to celebrate Catholic Mass by that time. As Culture Minister Rima Abdul-Malak explained, while tourists will be able to visit the site in late 2024 and attend Mass, renovations will continue into 2025.

Does it seem strange to celebrate Catholic liturgy in a half-finished construction site? Perhaps, but the French are the ultimate authority on the “chic, messy effortlessness” that results from a project left not-quite-done. Plus, those feeling impatient may quench their thirst for Notre-Dame de Paris by arriving in Paris, post-haste! A new exhibition has opened, entitled “Notre-Dame de Paris: at the heart of the construction site.” Visitors can expect to reap the inside scoop of the on-going renovation, plus view some remains from the fire, as well as salvaged artwork from the Cathedral.

In truth, the delays that have pushed back the opening, and made the aforementioned exhibit possible, are likely a good sign. The extended time for renovations signifies the seriousness and care being put into this renovation by the expert team on the ground in Paris. This is not surprising, seeing that the Cathedral is a highlight along tourists’ itineraries, and the structure has inspired generations of artists and writers.

The situation is as poet Mary Oliver wrote: “Things take the time they take. Don’t worry. How many roads did St. Augustine travel, before he became St. Augustine?”

One of the classic gargoyles atop Notre-Dame, photographed in 2016. Image courtesy Marcok via Wikimedia Commons.

Who is the genius leading this team of experts? The man entrusted with this special renovation project is none other than famed architect Philippe Villeneuve. According to Paris’s Official Tourism site, Villeneuve’s plan from the get-go has been to “rebuild the cathedral identically, including the spire.” The architect’s mission to retain the building’s original structure seems to be the foundation from which all other decisions are made. Even so, some of the plans have departed from the Cathedral’s original design. This has caused quite a bit of drama. The reason for the drama is that, unsurprisingly, there have been a lot of opinions about how the phoenix of Notre-Dame de Paris should rise from the ashes.

The online rumor mill has added fuel to the fire. Last year, rumors surfaced regarding plans to depart from the Cathedral’s original plans, sacrificing austerity for new tech and additional features. This caused widespread concern among art experts and historians that the Diocese of Paris was attempting its own “woke Disney revamp.” Plans to create features such as “emotional spaces” and “a discovery tour” sparked French academics to doom the proposals as an example of “inanity [meeting] kitsch.”

A contemplative gargoyle on the North Bell Tower in 2018, perhaps foreseeing the coming fire. Image courtesy Mari Doucet via Wikimedia Commons.

The “woke Disney revamp” comments ironically threw serious shade on the media powerhouse that brought new fame to Notre-Dame in the 1990s with the release of the animated film The Hunchback of Notre Dame. When approached for comment about the unfavorable comparison, Mr. Mickey Mouse chose not to respond. Those familiar with the matter claim that Mr. Mouse had suggested sending a “poop emoji” to the art historians’ to counter the vitriolic attack, but was dissuaded by publicity experts from doing so.

Despite criticism of any change from the original design, France’s National Heritage and Architecture Commission has approved several proposals integrating modern updates. These include installing modern lighting and contemporary works. Strong adherents to the traditional Gothic integrity of the space oppose such changes; on the other side, the Cathedral’s pastoral staff claim that some changes to the original plan will make the experience of visiting the Cathedral more enjoyable overall.

Additional controversial proposed changes favored by the Diocese include moving the tabernacle and other sacred objects. The purpose behind these changes is to encourage more of a dialogue between the visitor and the Gothic architecture of the sacred space when walking through the space. French authorities hope that these changes will retain the traditional feel of the original layout, while “bringing more a little more sense to the visitor.” As these changes seem directed at easing crowd flow for when the Cathedral is once again a major tourist site, they have faced fewer critics.

Lookout for the Spire

When word broke loose that there were plans to significantly change the monument’s overall architecture, the French Government got involved, to make sure that crucial elements of the Cathedral remain the same. At one point, a change to the iconic look of Notre-Dame was suggested in the form of a new, more modern spire. In response, President Emmanuel Macron intervened. He had been approached by cultural heritage experts who convinced him that a dramatic overhaul in design would drastically alter the integrity of the globally recognized monument. Macron stepped in to nix the change and prevent the 19th-century spire from being replaced with a more contemporary update. Reconstruction of the spire did not start until last year, because the monument itself had to undergo significant reconstruction to be able to support the 315 ft spire. True to his word, Macron has ensured that the new spire will match the one lost by fire. Those scanning the Parisian skyline will once again see the fabled towers in renewed glory.

A History of Renovations

Many people will be surprised to learn that the so-fought-for spire was not, in fact, part of the original 12th century Gothic design. The iconic Notre-Dame de Paris spire that the world knows and loves was added in the 19th century, by architect Eugène Voillet-le-Duc. Voillet-le-Duc’s involvement was the result of a major renovation effort at that time, spurred into life by renewed interest in the Cathedral following Victor Hugo’s famed tale.

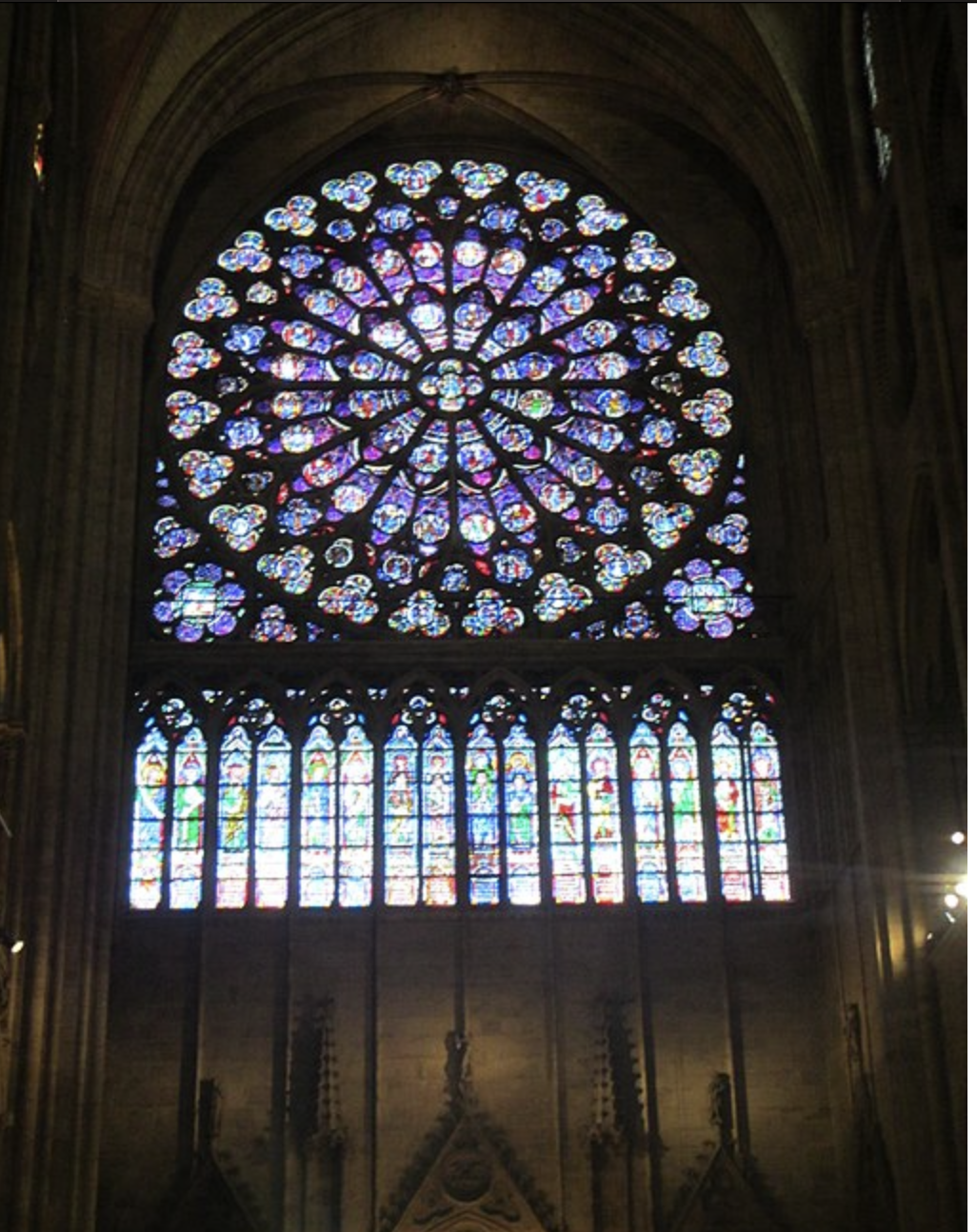

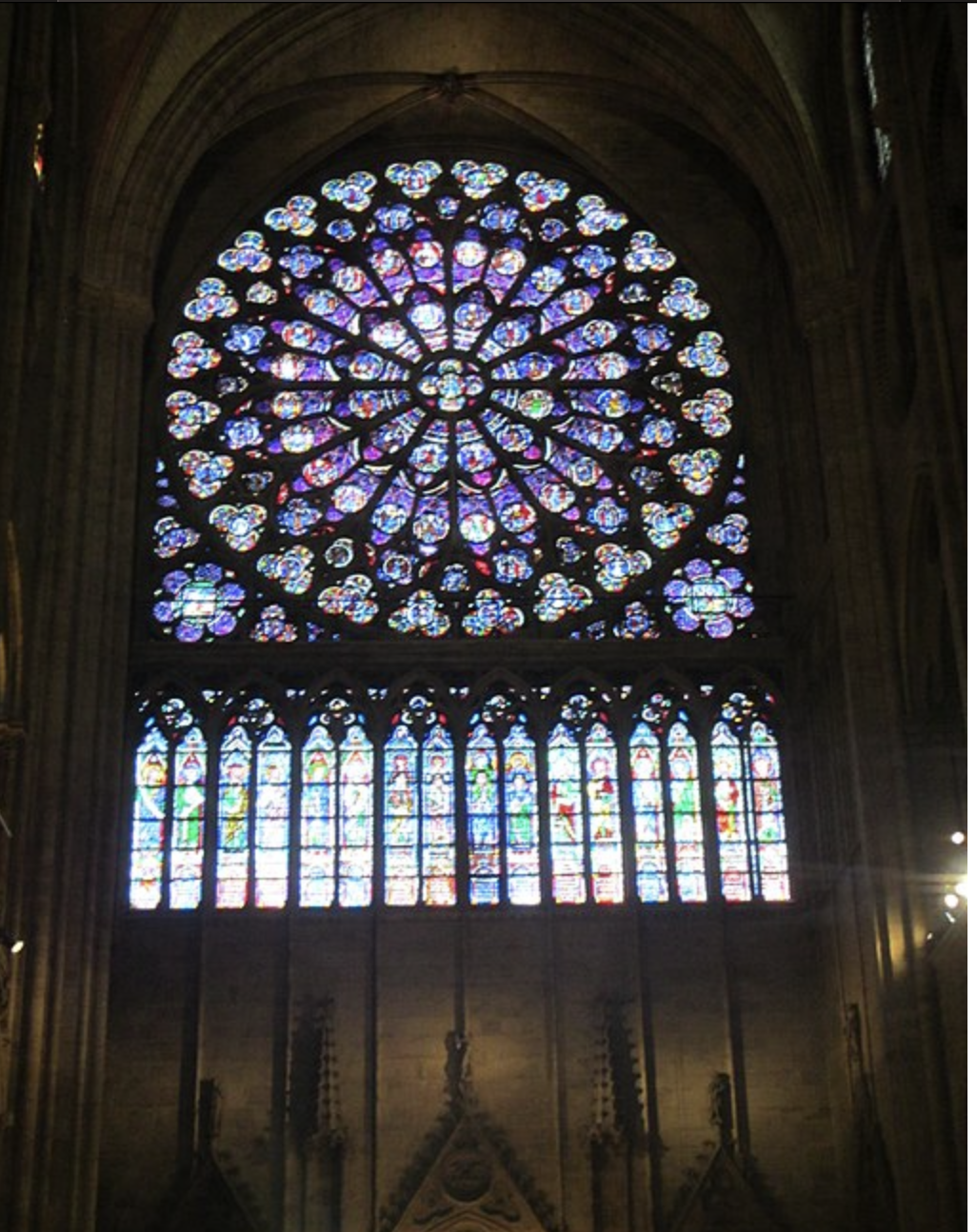

Notre Dame Rose Window in 2014. Image courtesy Jeremy Hylton via Wikimedia Commons.

That effort led by Voillet-le-Duc marked the most recent major renovation of Notre-Dame de Paris, but not its first major revamp. In 1699, the Cathedral received a major facelift in 1699, courtesy of the redecoration effort led by Hardouin Mansart and Robert de Cotte. Prior to that, several reconstruction and renovation efforts occurred, including the installment of the north and south rose windows.

In fact, the entire conception of Notre-Dame de Paris as we know it was the result of a major reconfiguration of sacred space. The original construction of Notre-Dame de Paris, commissioned by Bishop Maurice de Sully in 1163, replaced a demolished 4th century Cathedral of Saint Étienne. In that sense, one could argue that Notre-Dame de Paris has been an HGTV special from Day One.

The Future of Notre-Dame

Will this next reveal mark the final glow-up of this storied monument’s life? Or is this version of Notre-Dame de Paris simply another notch in the belt of this hero’s journey? If anything, this is a cathedral that has proved it knows how to reinvent itself and start anew. Plus, with the aid of new technology, the state-of-the-art Cathedral will be even more regal than before. Hopefully, 2019 was the last time Notre-Dame de Paris will face a fire. A renewed and refreshed cathedral will be worth the wait – and will stand for many centuries to come as a symbol of courage and resilience in the face of inferno.