Anyone who has been a student knows that the fastest way to capture someone’s attention in a noisy cafeteria is to start a food fight. Last summer and fall, something similar happened in the art world, as museums became the backdrop for messy protests. Now, after a short repose, the culprits are at it again. This time, the action is taking place in Italy, with the most recent attack on art having occurred on March 17th in Florence.

Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy. Image via JoJan through Wikimedia Commons.

Wait, What’s Going On?

The targets are priceless pieces of art and cultural heritage. The culprits are climate activists from several distinct groups with the same singular message: pay attention to climate change. The settings are (formerly) peaceful, as in this last attack in Florence.

In Florence, climate activists disrupted an ordinary day by spraying paint over the outer walls of Palazzo Vecchio. That attack on cultural heritage comes on the heels of the destructive actions taken against artwork in museums around the globe. Soup, cake, ink, and even super glue have been haphazardly applied to the most famous works of art in museums’ prized collections within the past year.

Many of these attacks occurred last summer and fall. Then, around the New Year, there was a brief repose. Art world insiders were optimistic that this trend would stop entirely. Time Magazine reported earlier this year that one major group, Extinction Rebellion, had announced a shift away from flashy civil resistance tactics to gain support for their cause. Instead, the group stated their plan to devote energy to large-scale protests that do not break the law. If other climate change groups followed suit, this would mean a dramatic departure from the ink-splattering and soup-slinging tactics directed at fragile pieces of art and cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, a change in tactics does not seem to be the cards. Not only was the fear that these attacks would continue realized by the recent protest in Italy, a quick check-in with the notorious Just Stop Oil climate activist group – of art attack fame – confirmed their general intention to carry on with the practices of last year. The group, in response to Extinction Rebellion’s statement, promised to “escalate” their actions of civil resistance and public disruption. The group even threatened to begin slashing famous paintings – yikes!

First Rule of Fight Climate-Change Club: Talk as Much as You Can About Fight Climate-Change Club

Van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. On view at The National Gallery, London.

The purpose of these art attacks is to get people talking. One recent attack last November was from a group called Last Generation Austria, in protest of Austria’s reliance on fossil fuels. Two activists threw black liquid (presumably representing oil) at the delicate 1915 painting Death and Life (1915) by Gustav Klimt. One activist was promptly removed from the scene by security. The second succeeded in gluing his hand to the glass panel encasing Klimt’s valuable painting. This gluing action was a serious risk both to the safety of the dizzyingly priceless piece of cultural heritage behind the glass, and to the climate activist’s personal hand health. It seems the activist cared very much for climate change, but very little for his hand.

The above attack was likely inspired by the group that finds itself the major instigator of this global operation. Just Stop Oil (the O.G. art attack tribe of climate protestors) has been at this game since earlier last summer. The most publicized attack by Just Stop Oil featured a pair of activists throwing tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers. During the attack, two 21-year old activists leaped over the velvet ropes stationed in front of Van Gogh’s painting, removed their jackets to reveal matching “Just Stop Oil” t-shirts, and slapped soup onto the painting. Not only is this display of wanton disregard shocking, but it boggles the mind that the target of the soup-based attack was not a Warhol work!

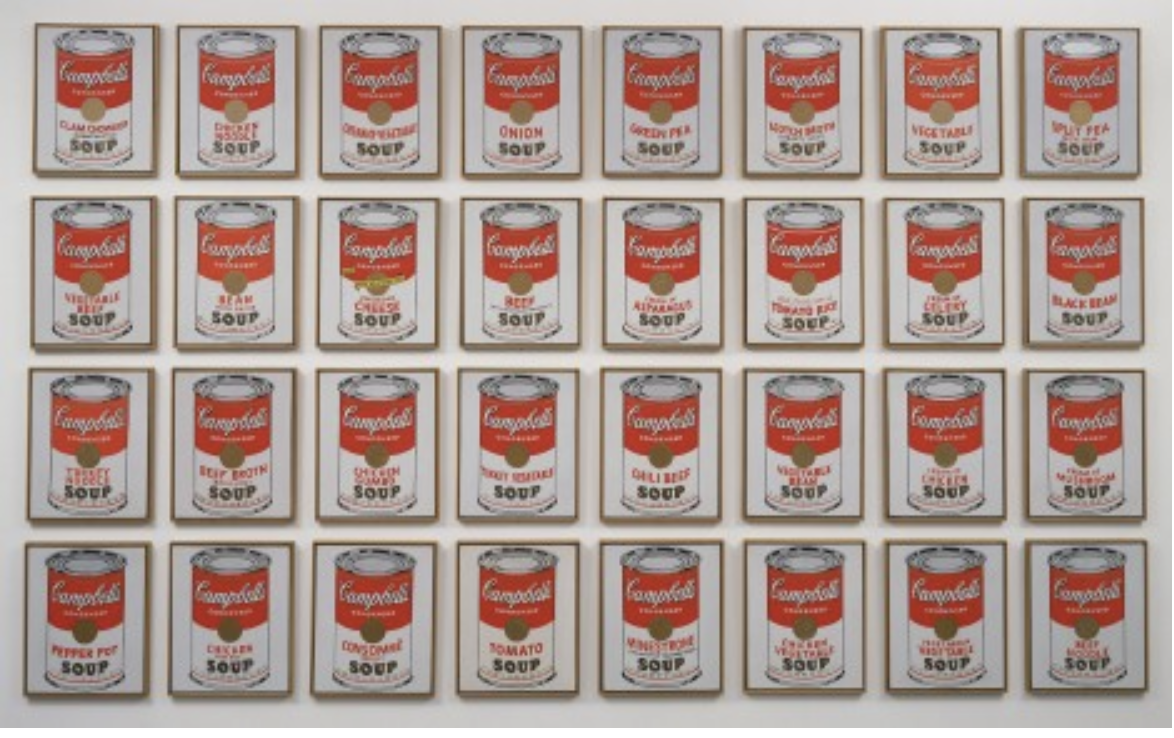

The attack seems to be connected to another recent event of art vandalism that took place that same month in the National Gallery of Australia. That incident involved members of a different group, Stop Fossil Fuels, scribbling ink on Andy Warhol’s screen prints of soup cans. The similarities cannot be ignored, as they follow a similar attention-mongering logic. However, why Just Stop Oil applied soup to varnish, while Stop Fossil Fuels applied varnish to soup, is a total mystery.

The above examples are merely a sampling of the demonstrative protests that have occurred in major museums since the beginning of the summer. They all follow a similar pattern: either a defacing with food or liquid, or protestors gluing themselves to a frame or glass. The latter is an imitation of the form of “locking” protest, in which activists will chain themselves to a stationary object to make it more difficult to be removed by authorities.

Fortunately, it seems that the works involved were unharmed, since they are protected by glass and other protective casings applied by art conservators. In the case of Just Stop Oil and Sunflowers, it was publicly known that the tomato soup would not damage the painting (according to Emma Brown, the founder of Just Stop Oil). Brown asserts that her group’s motivation has never been to destroy art. Rather, it is to engage in a conversation about why damaged artwork incites rage, while news reports of climate change do not.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Image via AP News.

This is not an illogical question, when framed in the proper context. However, when news reports of food being thrown in national galleries are splayed across individual computer screens, the intentions of Just Stop Oil’s efforts are lost in the absurdity of the situation. Food throwing, it seems, is better left in the era of summer camp hijinks.

It seems that the message may have been lost on the public, and that the method of protest may be too radical. In this way, they may be ostracizing potential friends of the cause by turning them off with their flamboyant and messy displays of passion. This would result in the activists seeming to be more like vandals to be avoided, rather than potential friends to be admired.

In fact, these stunts create animosity with museums and the public. By using art to stage protests, museums are now heightening security, leading to a less personal experience at art institutions. Increased security measures and the temporary removal and cleaning of artworks is an added expense for our public institutions. After significant drops in revenue during COVID pandemic, the last thing museums need is to waste funds cleaning up after these messy stunts.

Iconoclasm and Art Vandalism

Just Stop Oil’s flashy protests are not the first instances of art vandalism, nor will they be the last, as art vandalism has a long history of activists using destruction to send a political message. Dr. Stacy Boldrick, author of Iconoclasm and the Museum, explores the history of iconoclasm, which she defines as “image-breaking.” Public perception of iconoclasm influences how the broken image enters a culture’s consciousness, which can result in an almost secondary, separate work of art that begins a life of its own. Even if the piece is restored to its original glory, photos of the work in its defaced form become famous symbols of a particular political movement.

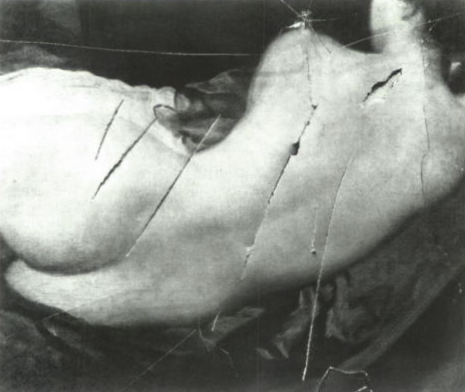

An example of this is none other than the famous Rokeby Venus, and its slashing by suffragette Mary Richardson in protest of the oppression of women. Readers of the blog will recall our firm’s piece on work (for a refresher, click here), and its haunted provenance. The history of the work influenced newspapers of the time to claim Richardson was acting from psychosis induced by Venus’s beauty. Boldrick, on the other hand, makes an argument for Richardson as a legitimate defender of the rights of women, though one who took her message to the extreme. Setting Richardson’s mental state aside, the images of the slashed Rokeby Venus are nearly as impactful as the restored version. The photos of the slashed painting draw the eye toward the ostentatiousness of Venus’s body, framing the voluptuous woman in a context of forced femininity.

The slashed Rokeby Venus. Image via artinsociety.com

Another example of a defaced work sparking its own conversation occurred following artist Tony Shafrazi’s 1974 defacing of Picasso’s Guernica. Shafrazi strode up to Guernica and spray painted “KILL LIES ALL” across the piece, in protest of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Fortunately, the painting itself was protected by a heavy coat of varnish. Museum curators were able to quickly clean off the spray paint. Even so, the photos of the defaced work, prior to the cleaning, became political messages. Moreover, Shafrazi himself went on to use the fame garnered by his demonstration to fuel his own artistic career. He is currently still doing well as a successful gallery owner and art dealer in New York.

Shafrazi proves that images of defaced art can send a cultural message by spreading the agenda of the activist who vandalized the work. However, sending a message does not always result in actual change on an individual level. If activists truly desire to change public behavior, there are more effective ways to evoke such action – ways that do not involve defacing fragile, famous works of art. Additionally, museums themselves can take action to promote sustainable, collaborative conversations with activist groups, all while keeping the art safe (and away from tomato soup).

Special Exhibitions

The North Carolina Museum of Art put on an exhibition this past summer that would have appealed to Just Stop Oil’s team of activists, because the show featured artists whose work brings attention to the dangers of climate change. The show, Fault Lines: Art and the Environment, featured artists such as Willie Cole, who did a site-specific installation of a chandelier made entirely out of single-use plastic water bottles. Another artist, Richard Mosse, exhibited works that used infrared technology applied to aerial photographs of geological locations to raise awareness of issues such as deforestation. Featured works of Mosse included: Aluminum Refinery, Paraguay; Burnt Pantanal III; Juvencio’s Mine, Paraguay; and Subterranean Fire, Pantanal.

Richard Mosse, Girl From the North Country, 2015. Image via artsy.net.

Also shown in the exhibit were works created by sisters Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim, whose whimsical crocheted coral reef draws attention to the devastating impact of climate change and plastic trash on the lives of coal reefs. The sisters also did an installation called The Midden, which was constructed of the trash the duo collected walking on the beach over a period of four years.

This writer, a visitor of the exhibit, was particularly influenced by the Wertheim’s trash collecting piece and by the plastic bottle chandelier by Cole. As the writer herself was sipping from a single-use plastic bottle, she was made aware of her personal impact on climate change as a visitor of the exhibit. The writer immediately vowed to use reusable water bottles from that moment on. She joined others on the way out of the exhibit in pledging to reduce all single-use plastics by dropping a recyclable token into the glass canister provided by the front door.

The purpose of the exhibit was to use video, photography, sculpture, and mixed-media works to offer new perspectives in addressing urgent environmental issues. The exhibit highlighted the consequences of inaction, while providing opportunities for patrons to take their own steps towards sustainable environmental stewardship and restoration. This resulted in a celebration of the creation, rather than the destruction, of art in its fullest capacity to send a message to society. By focusing on creation, patrons were encouraged to be part of a constructive solution to climate change alongside the artist activists who produced the pieces shown in the gallery. When asked how about the public response to the exhibit, Virginia Ambar, Assistant Director of Ticketing and Visitor Experience at NCMA said this: “Many people commented on how important it is to highlight our collective roles in affecting our environment and that the exhibit did that in ways that were both startling and beautiful.”

Museum Joint Statement

One way museums have been guarding themselves against art attacks has been to increase private security methods on museum grounds. These increased security measures have taken the form of additional guards, added cameras, and metal detectors – which all come with their own costs. Increasing security is a pricey endeavor, and not one that most museums have the budget for, particularly coming out of the hardships museums faced during the pandemic lockdowns.

Another option is for major public institutions to continue releasing joint statements concerning these matters. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) released a statement signed by over 90 museum leaders. Included among the high-profile supporters were figures from the Prado, the Guggenheim, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The statement explains the precariousness of the art being targeted, and highlights the vulnerability of delicate works of art, even when they are protected behind glass. While the statement does not address the issues raised by climate change, it does draw a clear line in the sand to draw attention to the riskiness of targeting these fragile and irreplaceable treasures.

Climate protestors march through city centers, causing traffic delays. Image via juststopoil.org

It is a showing of museum solidarity against protests. Its impact is yet to be seen, but there is hope that the statement will have an impact on protestors. The breadth of the ICOM statement, combined with the released statement by the American Association of Museum Directors on the same topic, last year, might speak to the protestors in a way that results in fewer art attacks. Taken together, the statements serve to highlight the damage caused by targeting art and the vulnerability of objects used in protests, without casting judgment on the protestors’ message. Rather, these statements encourage compassion on a global scale. Being good stewards of art and advocates for the environment both involve recognizing ways to nurture our shared humanity.

Conclusion

Collaboration is a better way forward than flashy protests. The lifespan of a shocking protest is only that of the flash-in-the-pan clickbait headline. As such, the political messaging of Just Stop Oil continues to be lost in the noise of the internet. Moreover, the fact of the matter is that throwing food at art to send a message is not sustainable. The shock value wears off eventually. It also wastes food and paint, not to mention the environmental impact of cleaning up the destruction. Remember the Italian climate activists’ recent activity in Florence? Ironically, even their spray painting seems to have caused more environmental harm than good. Nardella, the mayor of Florence, reported that “more than 5,000 liters of water were consumed to clean up Palazzo Vecchio” following the destructive protest.

Art, on the other hand, is constantly reinventing itself in sustainable ways that are fresh and exciting. Because of art’s evolving nature, activists who choose to work with artists and museums in a constructive, rather than a destructive, way, have the potential to sustainably effect real social change.

It’s a framework for elevated discourse. It smells like progress, not tomato soup.