by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 27, 2023 |

We are thrilled to announce the newest publication from associate Maria T. Cannon. Her latest article, “The Need for Speed: Why Recovery of Missing Art Needs an Upgrade,” was published in the ABA’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Newsletter, Spring 2023 Edition.

The Dutch Room with empty frame at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, site of the most notorious art theft in modern history (2016). Image via

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo Credit: Sean Dungan.

The piece discusses a new take on art crime and looting. She highlights how recovering artwork is a race against time. Art, once stolen, is uniquely difficult to find. Moreover, because stolen art is often delicate, it is subject to physical deterioration. Legal channels to recover artwork often slow down the process. Another issue can come from law enforcement. To recover major stolen works of art, the U.S. often relies on FBI agencies that lack crucial insider knowledge of local crime organizations. She acknowledges these difficulties, an offers creative solutions.

Want to read Maria’s article? Contact the ABA Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee for a full copy of this season’s great newsletter.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 22, 2023 |

Anyone who has been a student knows that the fastest way to capture someone’s attention in a noisy cafeteria is to start a food fight. Last summer and fall, something similar happened in the art world, as museums became the backdrop for messy protests. Now, after a short repose, the culprits are at it again. This time, the action is taking place in Italy, with the most recent attack on art having occurred on March 17th in Florence.

Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy. Image via JoJan through Wikimedia Commons.

Wait, What’s Going On?

The targets are priceless pieces of art and cultural heritage. The culprits are climate activists from several distinct groups with the same singular message: pay attention to climate change. The settings are (formerly) peaceful, as in this last attack in Florence.

In Florence, climate activists disrupted an ordinary day by spraying paint over the outer walls of Palazzo Vecchio. That attack on cultural heritage comes on the heels of the destructive actions taken against artwork in museums around the globe. Soup, cake, ink, and even super glue have been haphazardly applied to the most famous works of art in museums’ prized collections within the past year.

Many of these attacks occurred last summer and fall. Then, around the New Year, there was a brief repose. Art world insiders were optimistic that this trend would stop entirely. Time Magazine reported earlier this year that one major group, Extinction Rebellion, had announced a shift away from flashy civil resistance tactics to gain support for their cause. Instead, the group stated their plan to devote energy to large-scale protests that do not break the law. If other climate change groups followed suit, this would mean a dramatic departure from the ink-splattering and soup-slinging tactics directed at fragile pieces of art and cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, a change in tactics does not seem to be the cards. Not only was the fear that these attacks would continue realized by the recent protest in Italy, a quick check-in with the notorious Just Stop Oil climate activist group – of art attack fame – confirmed their general intention to carry on with the practices of last year. The group, in response to Extinction Rebellion’s statement, promised to “escalate” their actions of civil resistance and public disruption. The group even threatened to begin slashing famous paintings – yikes!

First Rule of Fight Climate-Change Club: Talk as Much as You Can About Fight Climate-Change Club

Van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888. On view at The National Gallery, London.

The purpose of these art attacks is to get people talking. One recent attack last November was from a group called Last Generation Austria, in protest of Austria’s reliance on fossil fuels. Two activists threw black liquid (presumably representing oil) at the delicate 1915 painting Death and Life (1915) by Gustav Klimt. One activist was promptly removed from the scene by security. The second succeeded in gluing his hand to the glass panel encasing Klimt’s valuable painting. This gluing action was a serious risk both to the safety of the dizzyingly priceless piece of cultural heritage behind the glass, and to the climate activist’s personal hand health. It seems the activist cared very much for climate change, but very little for his hand.

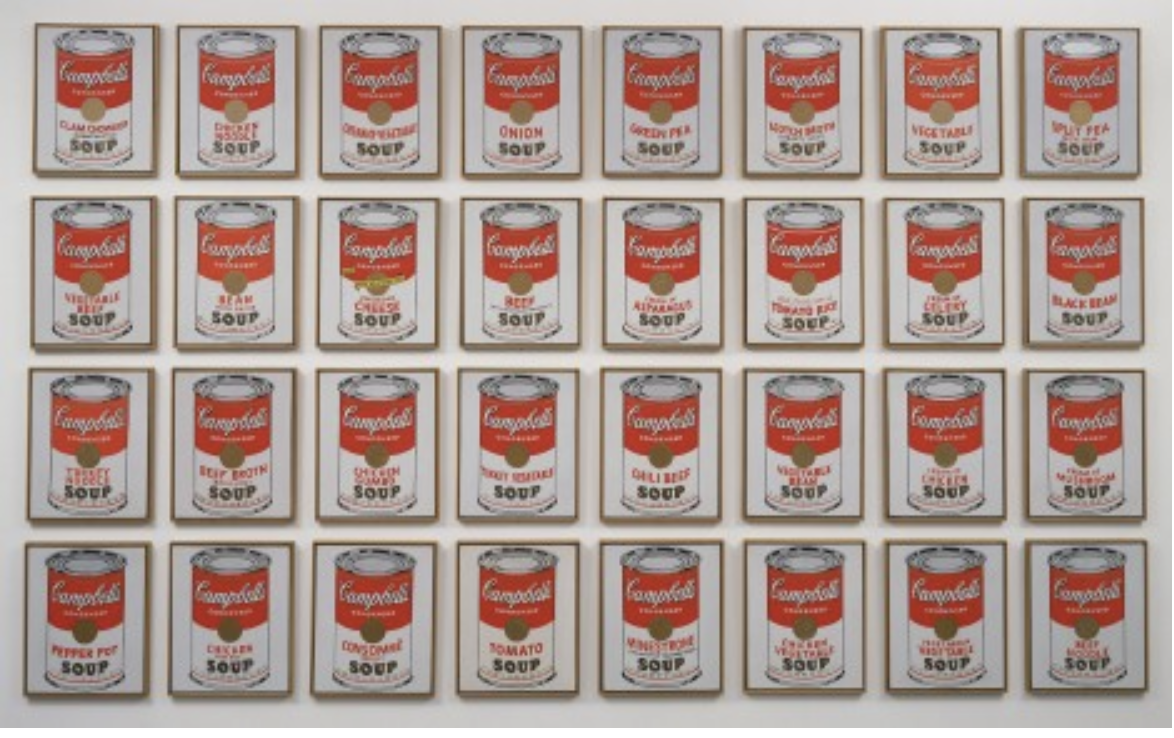

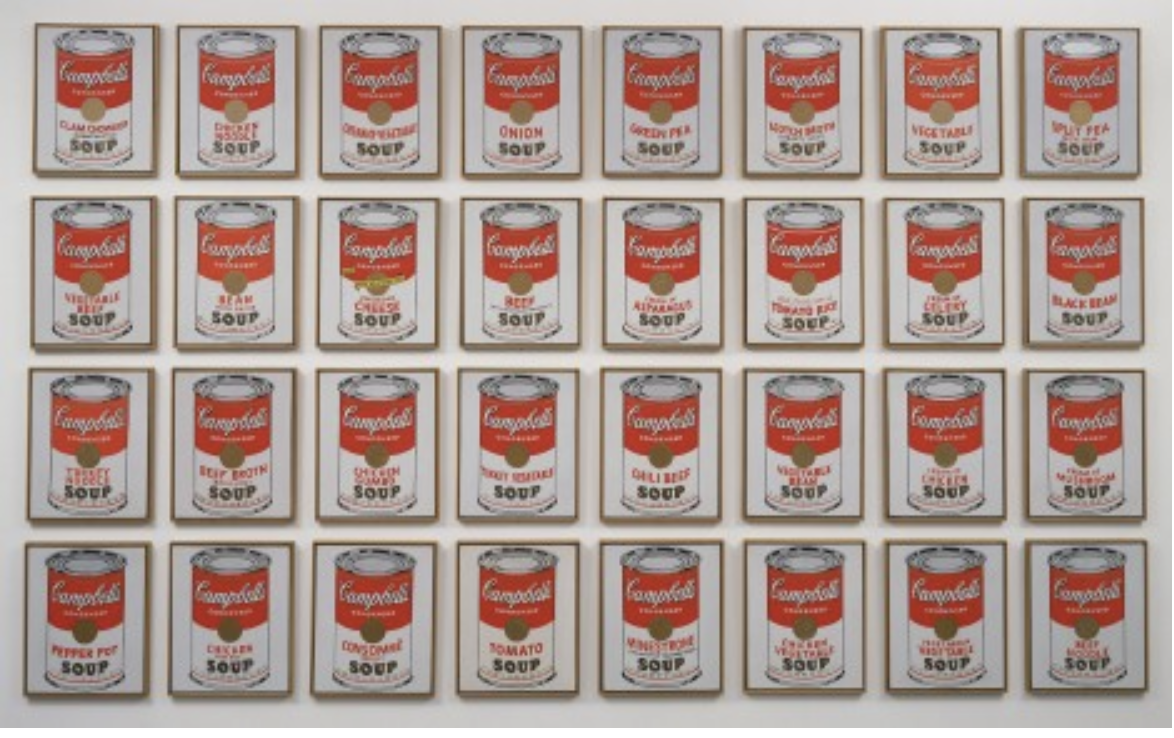

The above attack was likely inspired by the group that finds itself the major instigator of this global operation. Just Stop Oil (the O.G. art attack tribe of climate protestors) has been at this game since earlier last summer. The most publicized attack by Just Stop Oil featured a pair of activists throwing tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers. During the attack, two 21-year old activists leaped over the velvet ropes stationed in front of Van Gogh’s painting, removed their jackets to reveal matching “Just Stop Oil” t-shirts, and slapped soup onto the painting. Not only is this display of wanton disregard shocking, but it boggles the mind that the target of the soup-based attack was not a Warhol work!

The attack seems to be connected to another recent event of art vandalism that took place that same month in the National Gallery of Australia. That incident involved members of a different group, Stop Fossil Fuels, scribbling ink on Andy Warhol’s screen prints of soup cans. The similarities cannot be ignored, as they follow a similar attention-mongering logic. However, why Just Stop Oil applied soup to varnish, while Stop Fossil Fuels applied varnish to soup, is a total mystery.

The above examples are merely a sampling of the demonstrative protests that have occurred in major museums since the beginning of the summer. They all follow a similar pattern: either a defacing with food or liquid, or protestors gluing themselves to a frame or glass. The latter is an imitation of the form of “locking” protest, in which activists will chain themselves to a stationary object to make it more difficult to be removed by authorities.

Fortunately, it seems that the works involved were unharmed, since they are protected by glass and other protective casings applied by art conservators. In the case of Just Stop Oil and Sunflowers, it was publicly known that the tomato soup would not damage the painting (according to Emma Brown, the founder of Just Stop Oil). Brown asserts that her group’s motivation has never been to destroy art. Rather, it is to engage in a conversation about why damaged artwork incites rage, while news reports of climate change do not.

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Image via AP News.

This is not an illogical question, when framed in the proper context. However, when news reports of food being thrown in national galleries are splayed across individual computer screens, the intentions of Just Stop Oil’s efforts are lost in the absurdity of the situation. Food throwing, it seems, is better left in the era of summer camp hijinks.

It seems that the message may have been lost on the public, and that the method of protest may be too radical. In this way, they may be ostracizing potential friends of the cause by turning them off with their flamboyant and messy displays of passion. This would result in the activists seeming to be more like vandals to be avoided, rather than potential friends to be admired.

In fact, these stunts create animosity with museums and the public. By using art to stage protests, museums are now heightening security, leading to a less personal experience at art institutions. Increased security measures and the temporary removal and cleaning of artworks is an added expense for our public institutions. After significant drops in revenue during COVID pandemic, the last thing museums need is to waste funds cleaning up after these messy stunts.

Iconoclasm and Art Vandalism

Just Stop Oil’s flashy protests are not the first instances of art vandalism, nor will they be the last, as art vandalism has a long history of activists using destruction to send a political message. Dr. Stacy Boldrick, author of Iconoclasm and the Museum, explores the history of iconoclasm, which she defines as “image-breaking.” Public perception of iconoclasm influences how the broken image enters a culture’s consciousness, which can result in an almost secondary, separate work of art that begins a life of its own. Even if the piece is restored to its original glory, photos of the work in its defaced form become famous symbols of a particular political movement.

An example of this is none other than the famous Rokeby Venus, and its slashing by suffragette Mary Richardson in protest of the oppression of women. Readers of the blog will recall our firm’s piece on work (for a refresher, click here), and its haunted provenance. The history of the work influenced newspapers of the time to claim Richardson was acting from psychosis induced by Venus’s beauty. Boldrick, on the other hand, makes an argument for Richardson as a legitimate defender of the rights of women, though one who took her message to the extreme. Setting Richardson’s mental state aside, the images of the slashed Rokeby Venus are nearly as impactful as the restored version. The photos of the slashed painting draw the eye toward the ostentatiousness of Venus’s body, framing the voluptuous woman in a context of forced femininity.

The slashed Rokeby Venus. Image via artinsociety.com

Another example of a defaced work sparking its own conversation occurred following artist Tony Shafrazi’s 1974 defacing of Picasso’s Guernica. Shafrazi strode up to Guernica and spray painted “KILL LIES ALL” across the piece, in protest of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Fortunately, the painting itself was protected by a heavy coat of varnish. Museum curators were able to quickly clean off the spray paint. Even so, the photos of the defaced work, prior to the cleaning, became political messages. Moreover, Shafrazi himself went on to use the fame garnered by his demonstration to fuel his own artistic career. He is currently still doing well as a successful gallery owner and art dealer in New York.

Shafrazi proves that images of defaced art can send a cultural message by spreading the agenda of the activist who vandalized the work. However, sending a message does not always result in actual change on an individual level. If activists truly desire to change public behavior, there are more effective ways to evoke such action – ways that do not involve defacing fragile, famous works of art. Additionally, museums themselves can take action to promote sustainable, collaborative conversations with activist groups, all while keeping the art safe (and away from tomato soup).

Special Exhibitions

The North Carolina Museum of Art put on an exhibition this past summer that would have appealed to Just Stop Oil’s team of activists, because the show featured artists whose work brings attention to the dangers of climate change. The show, Fault Lines: Art and the Environment, featured artists such as Willie Cole, who did a site-specific installation of a chandelier made entirely out of single-use plastic water bottles. Another artist, Richard Mosse, exhibited works that used infrared technology applied to aerial photographs of geological locations to raise awareness of issues such as deforestation. Featured works of Mosse included: Aluminum Refinery, Paraguay; Burnt Pantanal III; Juvencio’s Mine, Paraguay; and Subterranean Fire, Pantanal.

Richard Mosse, Girl From the North Country, 2015. Image via artsy.net.

Also shown in the exhibit were works created by sisters Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim, whose whimsical crocheted coral reef draws attention to the devastating impact of climate change and plastic trash on the lives of coal reefs. The sisters also did an installation called The Midden, which was constructed of the trash the duo collected walking on the beach over a period of four years.

This writer, a visitor of the exhibit, was particularly influenced by the Wertheim’s trash collecting piece and by the plastic bottle chandelier by Cole. As the writer herself was sipping from a single-use plastic bottle, she was made aware of her personal impact on climate change as a visitor of the exhibit. The writer immediately vowed to use reusable water bottles from that moment on. She joined others on the way out of the exhibit in pledging to reduce all single-use plastics by dropping a recyclable token into the glass canister provided by the front door.

The purpose of the exhibit was to use video, photography, sculpture, and mixed-media works to offer new perspectives in addressing urgent environmental issues. The exhibit highlighted the consequences of inaction, while providing opportunities for patrons to take their own steps towards sustainable environmental stewardship and restoration. This resulted in a celebration of the creation, rather than the destruction, of art in its fullest capacity to send a message to society. By focusing on creation, patrons were encouraged to be part of a constructive solution to climate change alongside the artist activists who produced the pieces shown in the gallery. When asked how about the public response to the exhibit, Virginia Ambar, Assistant Director of Ticketing and Visitor Experience at NCMA said this: “Many people commented on how important it is to highlight our collective roles in affecting our environment and that the exhibit did that in ways that were both startling and beautiful.”

Museum Joint Statement

One way museums have been guarding themselves against art attacks has been to increase private security methods on museum grounds. These increased security measures have taken the form of additional guards, added cameras, and metal detectors – which all come with their own costs. Increasing security is a pricey endeavor, and not one that most museums have the budget for, particularly coming out of the hardships museums faced during the pandemic lockdowns.

Another option is for major public institutions to continue releasing joint statements concerning these matters. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) released a statement signed by over 90 museum leaders. Included among the high-profile supporters were figures from the Prado, the Guggenheim, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The statement explains the precariousness of the art being targeted, and highlights the vulnerability of delicate works of art, even when they are protected behind glass. While the statement does not address the issues raised by climate change, it does draw a clear line in the sand to draw attention to the riskiness of targeting these fragile and irreplaceable treasures.

Climate protestors march through city centers, causing traffic delays. Image via juststopoil.org

It is a showing of museum solidarity against protests. Its impact is yet to be seen, but there is hope that the statement will have an impact on protestors. The breadth of the ICOM statement, combined with the released statement by the American Association of Museum Directors on the same topic, last year, might speak to the protestors in a way that results in fewer art attacks. Taken together, the statements serve to highlight the damage caused by targeting art and the vulnerability of objects used in protests, without casting judgment on the protestors’ message. Rather, these statements encourage compassion on a global scale. Being good stewards of art and advocates for the environment both involve recognizing ways to nurture our shared humanity.

Conclusion

Collaboration is a better way forward than flashy protests. The lifespan of a shocking protest is only that of the flash-in-the-pan clickbait headline. As such, the political messaging of Just Stop Oil continues to be lost in the noise of the internet. Moreover, the fact of the matter is that throwing food at art to send a message is not sustainable. The shock value wears off eventually. It also wastes food and paint, not to mention the environmental impact of cleaning up the destruction. Remember the Italian climate activists’ recent activity in Florence? Ironically, even their spray painting seems to have caused more environmental harm than good. Nardella, the mayor of Florence, reported that “more than 5,000 liters of water were consumed to clean up Palazzo Vecchio” following the destructive protest.

Art, on the other hand, is constantly reinventing itself in sustainable ways that are fresh and exciting. Because of art’s evolving nature, activists who choose to work with artists and museums in a constructive, rather than a destructive, way, have the potential to sustainably effect real social change.

It’s a framework for elevated discourse. It smells like progress, not tomato soup.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Mar 6, 2023 |

“Continue to take all the risks and forever be curious.” – Shannon Riley, Co-founder of Building 180

In celebration of International Women’s Day, we are highlighting women in art history. Some readers may be unaware of the sheer number of working female artists during male-dominated artistic eras. If, for example, the Italian Renaissance only calls to mind the names of Ninja Turtles, and leaves out Italian Renaissance pioneer Fede Galizia, then this is a post to bookmark.

Fede Galizia (Italian, 1578–d. ca. 1630); Still life of peaches on a fruit stand with jasmine flowers and a tulip. Image obtained via artnet.com

Who was Fede? Not only the holder of an unusual name, which Microsoft Word is currently attempting to autocorrect to “FedEx,” but she was a female painter making strides in the art world alongside other Italian Renaissance greats. Her contribution to the still life genre may be compared with that of Caravaggio’s. Both were composing still lifes of fruit within the same decade – a rarity for this artistic era.

Details about Fede’s early life are few and far between, but it is likely that she faced societal pressures to prioritize domesticity over artistic training. But her knowledge of the household, gained by living with family throughout her childhood and early life, may have worked in her favor. It could be argued that her intimacy with domestic life gave her an edge in creating her iconic still lifes, over male counterparts like Caravaggio. If the men in her life thought that her obsession with making precise, detailed studies was “cute,” they were in for a surprise. Unbeknownst to them, this powerhouse of an artist was creating works that some critics today say surpass the skill and precision of her male counterparts. Her still life of peaches on a fruit stand with jasmine flowers and a tulip? Stunning. Take that, Caravaggio!

Fede also created distinctive miniatures, portraits, and altarpieces with incredible dedication to detail gleaned from her daily life. Her rendition of Judith with the Head of Holofernes, for example, purportedly features Judith as the self-portrait of the artist. The boldness required to use her own visage as inspiration speaks to the internal fortitude required for her to make art despite any societal pressures to engage more fully in domestic life.

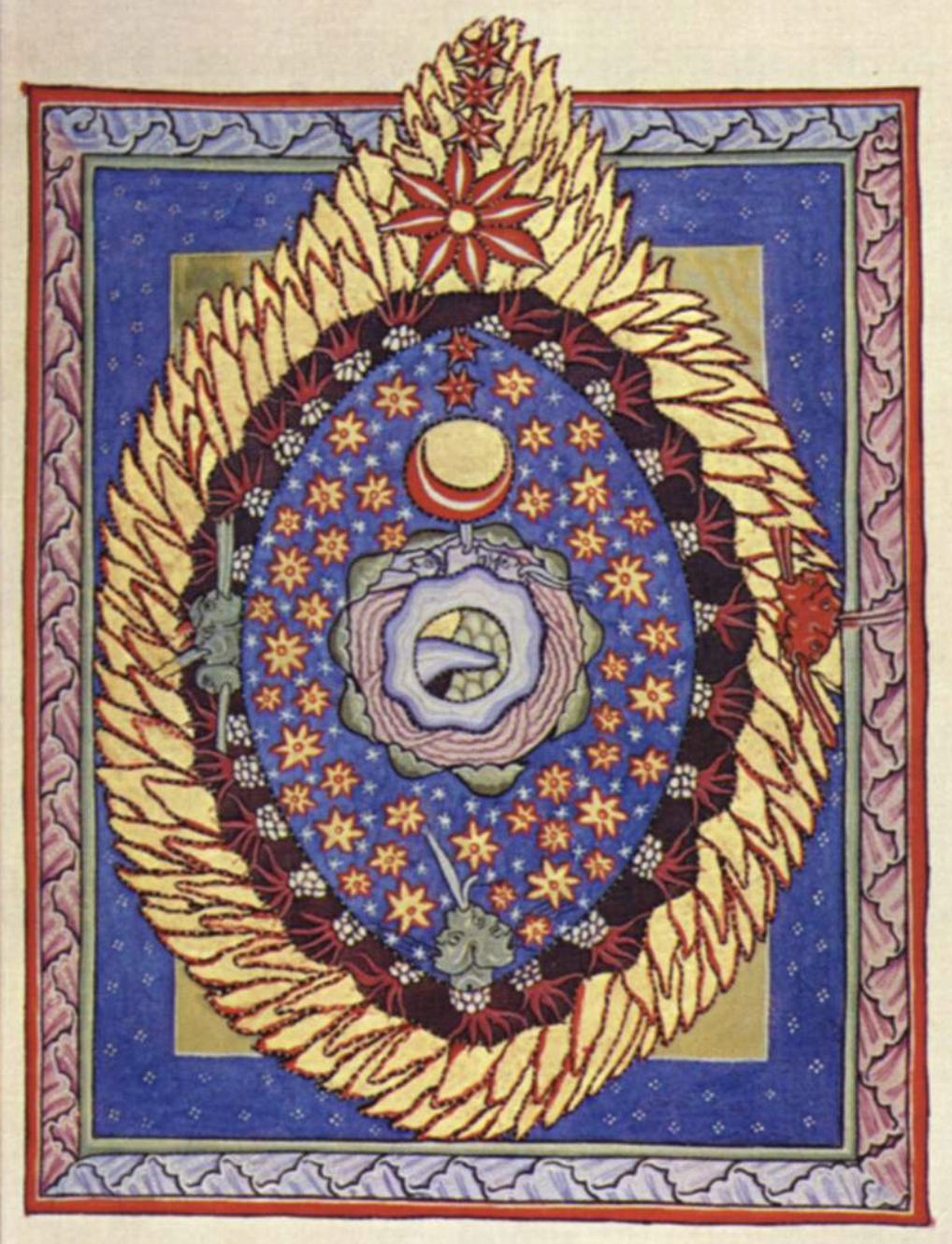

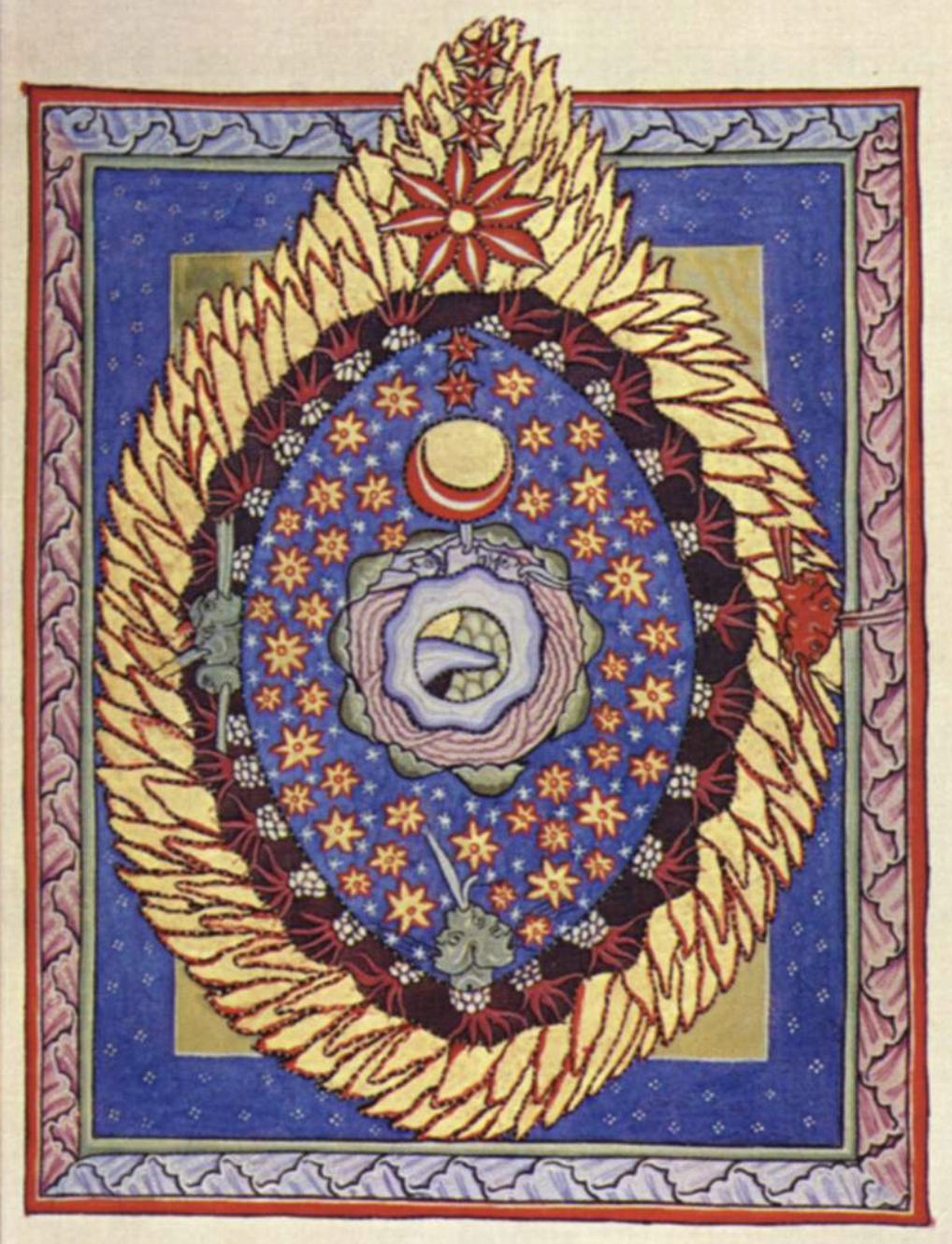

Hildegard von Bingen, Scivias, 1151. Image distributed via DIRECTMEDIA in public domain.

Another historical standout is the one-and-only Hildegard von Bingen, largely regarded as the original female artist. Hildegard von Bingen was a woman in possession of the ultimate multi-hyphenate of a bio. Ready? She was an artist/composer/writer/Catholic mystic/scholar/modern-day Catholic saint/ and one of four female Catholic Doctors of the Church. She was a busy woman. In terms of her artwork, she is particularly known for her illuminated manuscript Scivias, (or “Know the Ways”), created around 1150. This manuscript contains illustrations of a mystical vision she had. The vision revealed the universe to her as a “round and shadowy” composition that was sheathed in an “outermost layer of a bright fire.” To Hildegard, this vision spoke to the breath of life awakening the universe. Her use of dramatic themes, and her openness with her own mystical visions, reveal a tenacity of a woman who was bold beyond the cultural norms of women of the time.

If either of the above artists’ stories are new to readers, join the club – many women artists have been written out of traditional art canons. As a result, even art history majors may not know of as many female artists as they do male ones. Sadly, many female artists simply failed to gain recognition, despite their talent and genius.

Sculpture in SoMo Village. Artists: Joel Dean Stockdill and Yustina Salnikova. Located in Rohnert Park, CA. Image via Building 180.

Fortunately, today, tides are turning, and there has been a renewed, concentrated effort to remember women in art across the ages. Our firm previously wrote an in-depth post on women and the rediscovery of women artists. Read it here. The efforts to recognize previous women artists are essential in crafting a more complete and cohesive global artistic narrative across genres, genders, and stereotypes.

As important as it is to remember those women artists of yesterday, we also celebrate women in the art world today. Women are making bold moves in the art world, as artists, scholars, patrons, and business entrepreneurs. Included in this group is the standout women-owned business Building 180.

Building 180: Finding a Space & Filling a Need

Bee Line sculpture installed for Piatt Park. Artist: Inflatabill. Located in Cincinnati, OH. Image via Building 180.

Building 180 is a full-service global art production and consulting agency. The company fills the gap between artists and businesses to create public and private art installations in the form of murals, sculptures, and interiors. “Full-service” here means “full-service”: Building 180 handles the design, curation, and production of art installations from conception to completion. This includes budgeting, contracting, artist selection, fabrication, shipping, and management. Building 180 really shines in its role as intermediary, by streamlining communication between artists and site owners to make a smooth installation of the artwork (whether permanent or temporary).

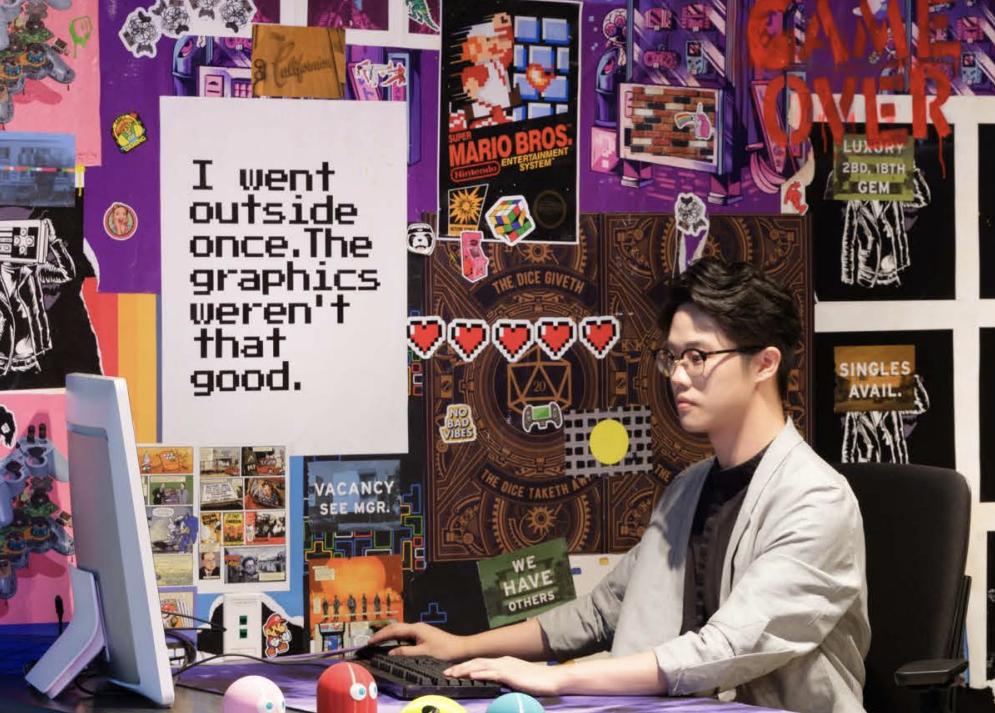

IT interior created for Twitch. Muralist: The Tracy Piper. Located in Los Angeles, CA. Image via Building 180.

Think of Building 180 as the Fairy Godmother of Cinderella’s art world: giving oft-overlooked artists their Glass Slippers and sparkly pumpkin carriage to arrive at the ball. Building 180 provides artists with the essentials needed to bring forth their best work, while simultaneously handling the often overwhelming logistical and business aspects of large-scale installations. The result is an open, approachable, communal experience of art living alongside viewers in the everyday.

The need for a business such as Building 180 cannot be undervalued. Contrary to popular belief, murals, sculptures, and gorgeous interiors do not simply appear overnight. They require attention to detail at all stages of the transaction. Because Building 180 orchestrates the installation from start-to-finish, working with both artists and business owners, the company makes the murky waters of bringing art to life in unexpected places not only possible, but peacefully navigable.

Bringing Art to the Community

Muralists stand back to gauge their work for Paint the Void. Image via Building 180.

At the heart of Building 180’s mission is to bring art to the community through strategic efforts to foster engagement and inclusivity. These goals are achieved through educational programming, invitations for project volunteers, and panel discussions aimed at identifying the needs and desired outcomes for the community.

The premier example of Building 180 bringing art to the community in an effective and mindful way occurred in the early stages of the pandemic lockdowns of March 2020. Paint the Void, Building 180’s non-profit, is the public mural initiative founded in early 2020. The goal of the organization? Commission artists to complete public murals using the plywood covering closed storefronts and windows of boarded-up businesses. The result has been a completion of over 230 murals. Building 180 partnered with over 35 different neighborhoods to install the works. In doing so, Building 180’s brilliant team has supported over 175 small businesses, engaged the help of over 2,000 volunteers, and seen 250 artists paid for their work.

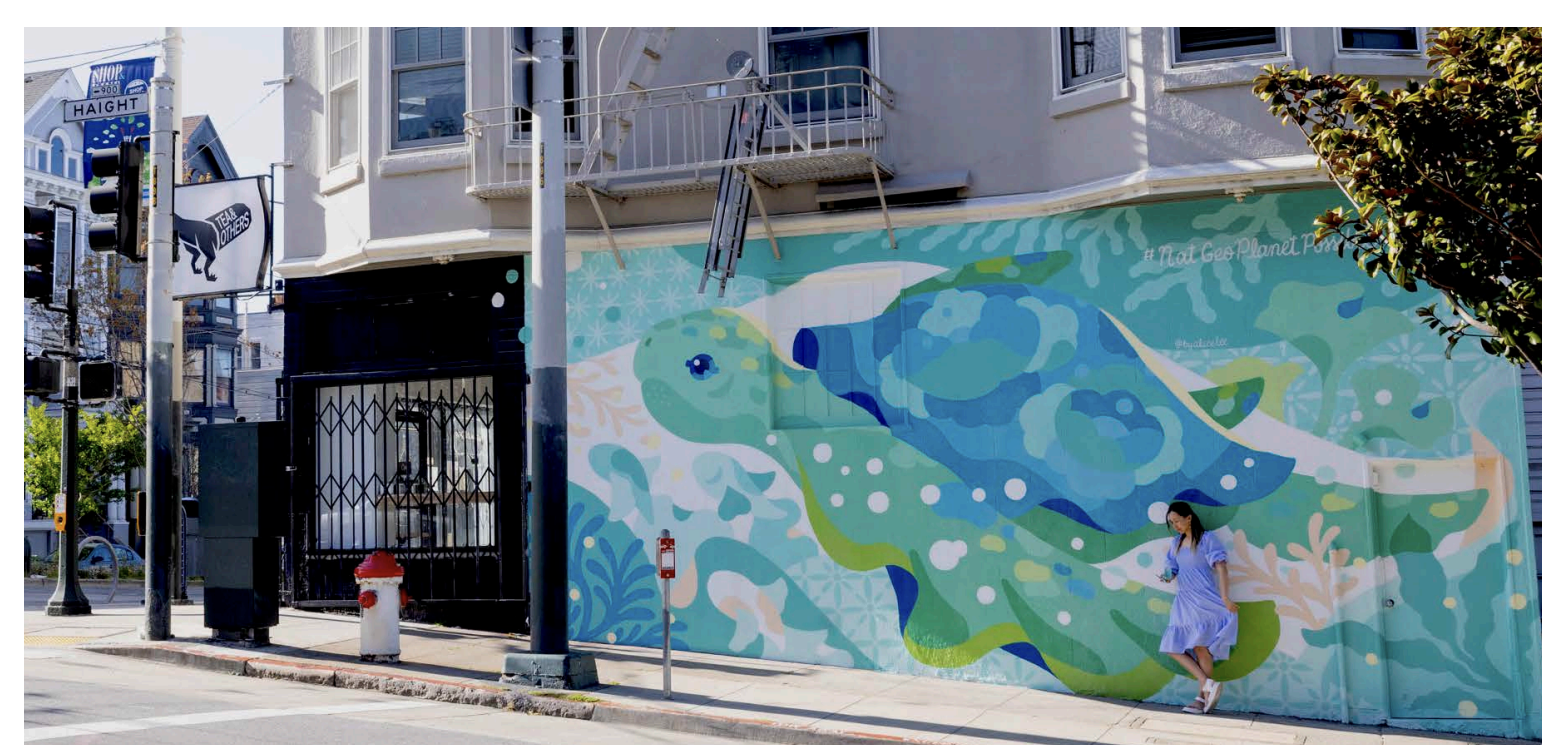

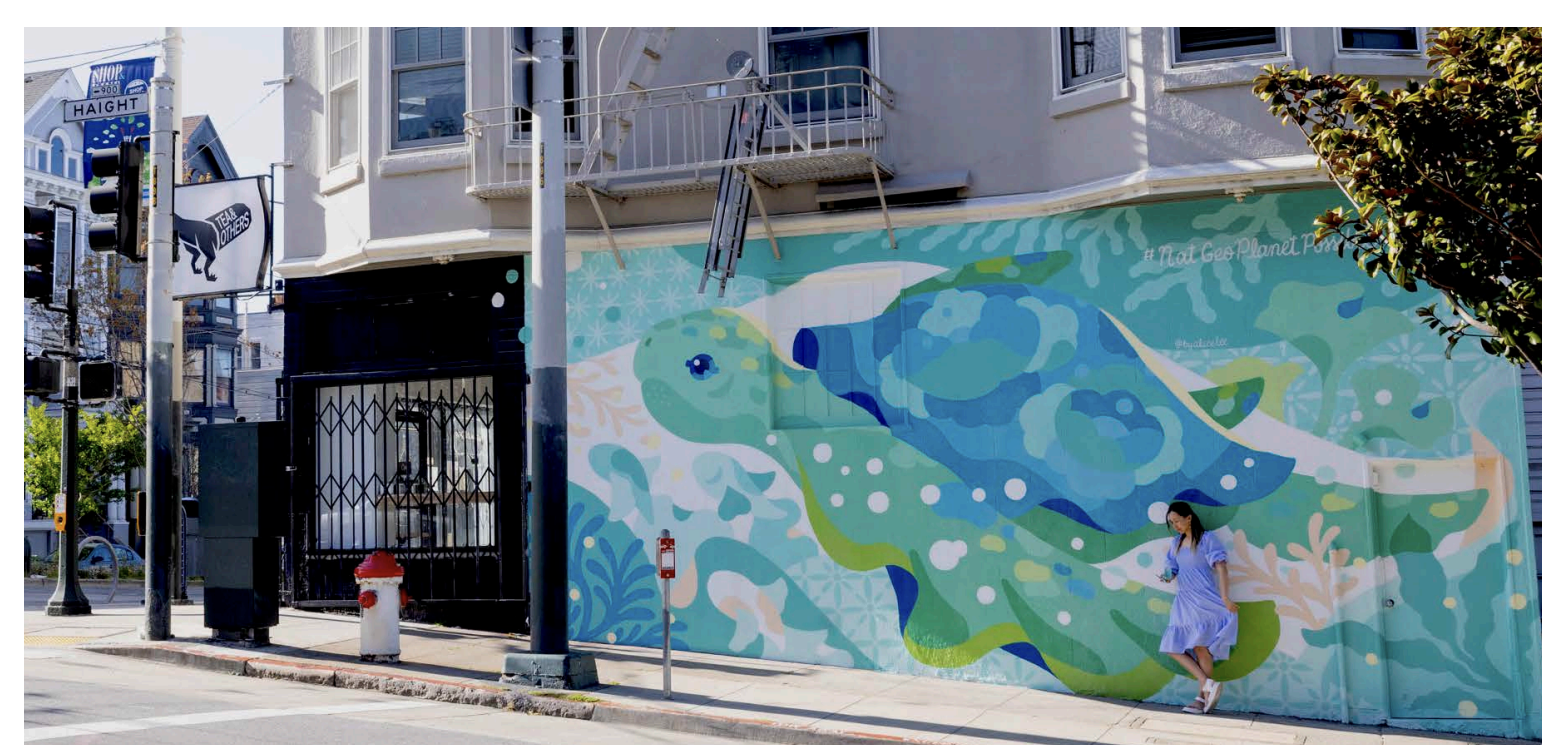

A ”snapshot” of this mural movement was recently on display in San Francisco, in the form of a retrospective. The City Canvas: A Paint the Void Retrospective featured 49 pieces from Paint the Void, including Nora Bruhn’s Keep Blooming, a pastel-colored floral that covered the boarded-up storefront of restaurant Chez Maman.

Save the Turtles painted for National Geographic. Artist: Alice Lee. Mural located in San Francisco, CA. Image via Building 180.

Bruhn’s piece is a fantastic example of the fundamental impact of the mural movement, and of Building 180 as a whole: to release the artistic power held within the daily lives of local communities. Building 180 accomplishes this impeccably, by marrying artists with businesses to find available space for art. These creative solutions employ artists and create economic opportunities for business owners – all while serving to spark the imaginations of all who encounter the works. The result? Communal resiliency and a deeper fascination with the power of art.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 1, 2022 |

A visit to the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto, MArTA) reminded me why I love museums so much. It is an inspiring place, a valuable educational resource, and an underappreciated repository for art and heritage.

Taranto, Italy

Greek ruins (Temple of Poseidon)

MArTA is located in Taranto, a city located along the inside of the “heel” of Italy in the region of Puglia. It was founded by Spartans in 706 BC, and it became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia (the Roman-given name for the coastal areas in the south of Italy — Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily — heavily populated by Greek settlers). Two centuries after its founding, it was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of around 300,000 people. Taranto (called Tarentum by the Ancient Romans) was subject to a series of wars, culminating in its fall to Rome in 272 BC. The city fell to Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but was recaptured (and subsequently plundered) by Rome in 209 BC. The following centuries marked the city’s decline.

Cathedral of San Cataldo

Taranto’s mix of architecture and rich cultural heritage is due, in part, to subsequent changes in leadership between the 6th and 10th centuries AD, during which time it was ruled by diverse groups: Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Arabs. Later, during the Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century AD, the city served as a French naval base, but it was ultimately returned to the Kingdom of Two Sicilies for a few decades before it officially became part of the Republic of Italy in 1861.

Due to its strategic location on the inlet of the Gulf of Taranto, the city has great naval importance. Taranto served the Italian navy during both World Wars. As a result, it was heavily bombed by British forces in 1940 (the bombing of Taranto and was even noted to have “set the stage for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor” the following year). The city was also briefly occupied by British forces during WWII.

Evidence of the city’s various iterations is evident throughout its streets with impressive cultural sites, including the Greek Temple of Poseidon, the Spanish Castello Aragonese (built in 1496 for the then-king of Naples, Ferdinand II of Aragon), and the 11th century Cathedral of San Cataldo (Taranto Cathedral), where the remains of the city’s patron saint, Saint Catald, lie (he is believed to have protected the city against the bubonic plague). More recent architectural gems include Palazzo Galeota and Palazzo Brasini.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MArTA)

Like the city where it is located, MArTA is a rich institution full of incredible treasures. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit MArTA in person. Sadly, the museum, and the city itself, tend to fall under the radar of tourists. It is unfortunate that this site escapes attention, because both Taranto and its vaunted museum are incredible.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

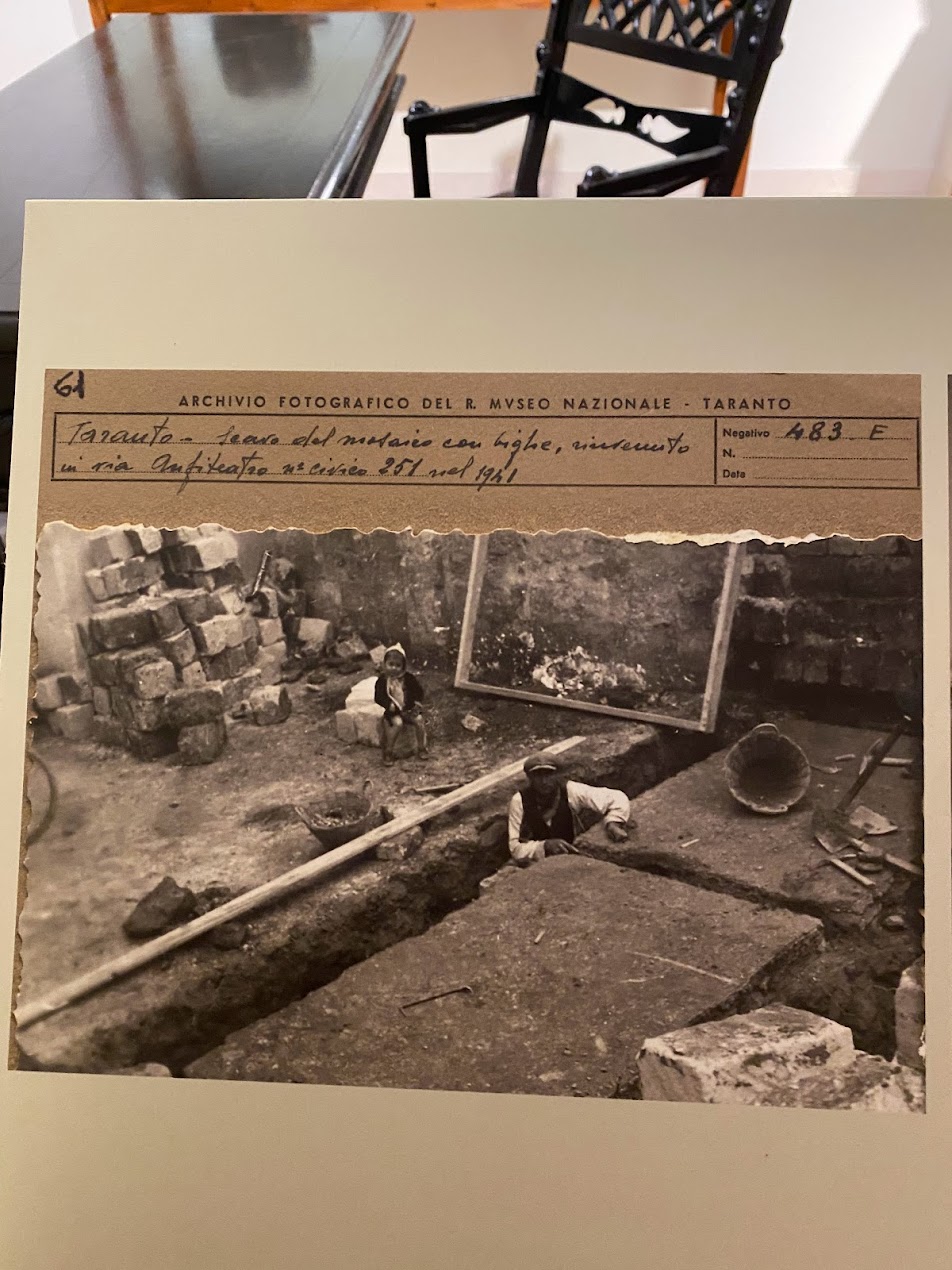

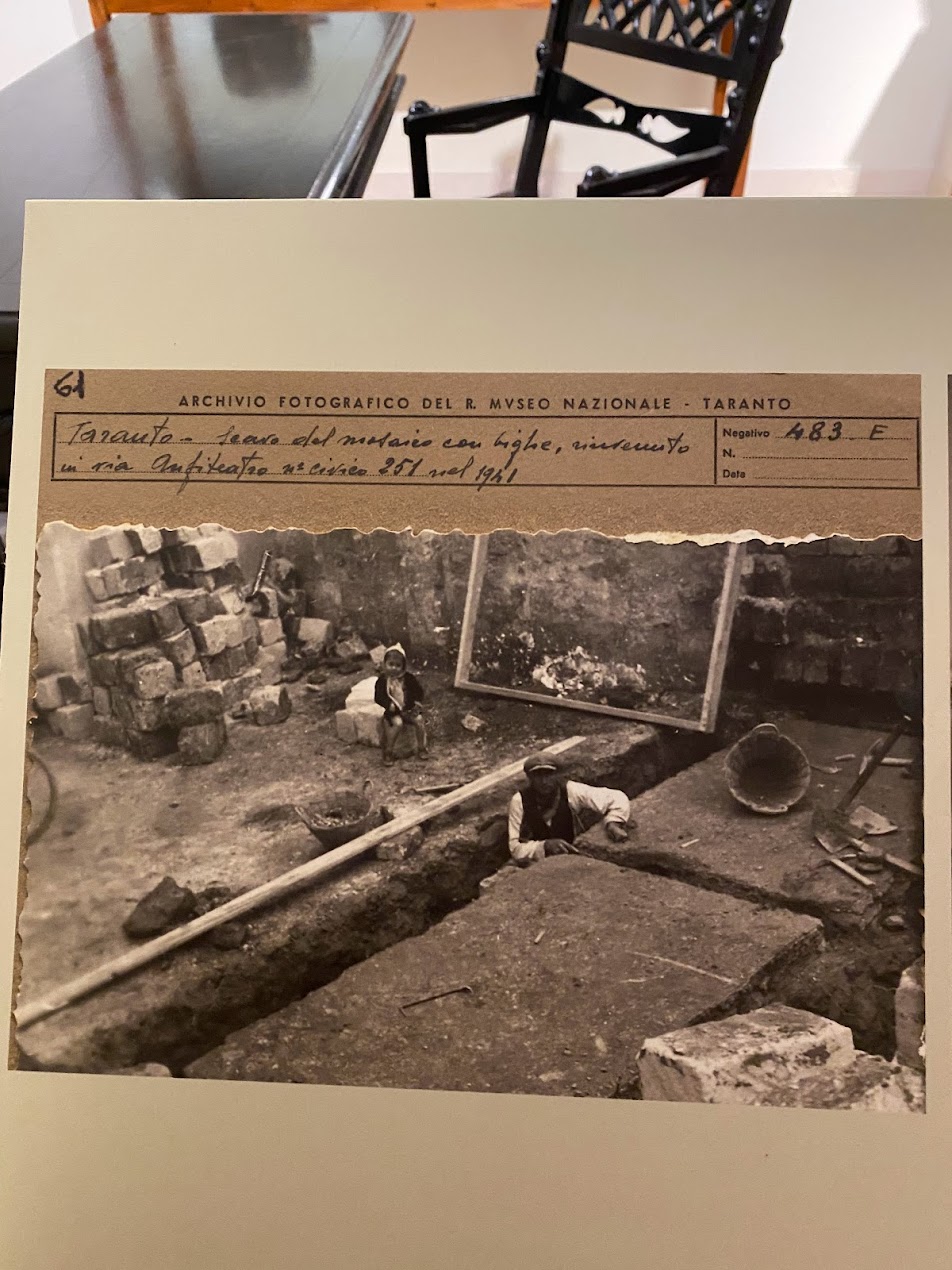

Amongst other treasures in MArTA are beautifully preserved mosaics, ornate golden jewelry, and ancient gold-covered snake skins. Another museum highlight are the informative displays positioning objects in creative contexts. For example, some objects are displayed along with photographic evidence and documentation about their excavation.

Tomb of the Athlete

The museum presents objects in beautiful vitrines. Some of the highlights on the first floor include thematic displays, such as a wall depicting Medusa’s face on antefixes found in Taranto. The curation includes information about the figure of Medusa in mythology and details on how her portrayal evolved over time. Another engaging display involves #italianmuseums4olympics, the Ministry of Culture’s campaign to support Italian sport and culture during the Olympic games. That particular display includes the sarcophagus of an athlete from Taranto, complete with amphorae found in his tomb that include images of athletic competitions, celebrating Italy’s long tradition of participating in the Olympics since antiquity.

An Apulian krater by the Darius painter returned from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2009

Looting of Objects on Display

As visitors enter the next floor of the museum’s route, they are confronted with a large restituted antiquity. A large Apulian krater by the Darius painter was returned to Italy in 2009 from the Cleveland Museum of Art after it was recovered by the Carabinieri’s TPC (the nation’s famed “Art Crime Squad”). The work was among fourteen artifacts returned from the Ohio museum after a two-year negotiation resulting from the investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici and Gianfranco Becchina, two well-known dealers of looted materials who sold antiquities at auction and through dealers to supply coveted objects to collectors and museums around the world.

Loutrophoros restituted by the J. Paul Getty Villa in Malibu in California

MArTA also acknowledges some of the people responsible for the development of its exquisite collection, including past directors and donors. The displays note that the illicit or unknown sale of antiquities has led to the loss of knowledge about their historical and cultural value (when artifacts are illicitly excavated and divorced from their contexts, valuable information is lost in the process). However, the development of patrimony laws has allowed the Italian government to control more of the archaeological discoveries taking place, and other legislation has also encouraged collectors to donate their property to the museum and Italian State. The display also notes the important work by law enforcement and its success in having works repatriated to Italy, as well as its success in confiscating looted artifacts from private owners and collectors during the 20th and 21st centuries in Italy. Part of this display features works returned from major museums abroad, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum in Malibu, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Labels and Information

The labels and information offered to visitors at the museum is exceptional, providing valuable information about the historic significance of items on display. Clearly, the museum places great importance on provenance, providing detailed information on where objects were excavated (this information includes exact find spots, with cross streets included for some of the objects), how they entered the museum’s collection, and ways in which the museum has evolved over the decades. Additional information is available to visitors about looting and criminal acts related to the objects, providing useful context.

Copy of the Goddess on Her Throne (the original is in Berlin)

One of the first objects to greet visitors upon their entry is a copy of a goddess on her throne. The original 5th century BC statue is “considered one of the greatest artworks from Magna Graecia.” It was found in 1912 in Taranto, but illegally exported out of Italy. It was then put on the Swiss art market, and finally purchased by the German government. It is currently on display at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Information like this is valuable, because it forces visitors to confront the political, societal, and cultural pressures facing museums, as well as the challenges and realities of the art and antiquities markets. It also provides a practical example of how works can wind up in international museums divorced from their original historical and cultural context.

As the museum’s website states, “The Museum also lends artefacts to other museums to allow global citizens to enjoy. We are aimed at providing first-hand information to all of our visitors so that they understand Europe’s prehistoric period.”

Castello Aragonese

A visit to this museum, and the gorgeous city of Taranto, with its sweeping coastal views, its rich cultural history, and its stunning architectural masterpieces, is essential for anyone visiting Puglia.

Copyrights in all photographs in this post belong to Leila Amineddoleh

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Objects from the museum’s early collection

Documentation of excavations

Vitrine (provenance information for each object is provided in a side panel)

Provenance on view

Beautiful entryways on each floor

Context with a photograph

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Aug 10, 2022 |

Museum dell’Arte Salvata (Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh)

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is proud to work as a leading law firm in the cultural heritage sector. We have worked with collectors, dealers, museums, law enforcement agencies, and even foreign governments. One of our clients is the Republic of Italy, a nation paradoxically blessed with an abundance of artistic and cultural treasures, but cursed with the solemn responsibility of protecting those treasures. Properly monitoring antiquities and archaeological sites, regulating the market, and protecting cultural heritage is a costly and heavy burden. Every region of the Italian nation is famed worldwide for its cultural treasures, and so the country has developed means to actively protect its heritage through various channels. For instance, Italy is the first nation in the world to have a military unit responsible for the protection of art and heritage.

The Carabinieri Headquarters for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, or TPC) was instituted in 1969. The TPC is a part of the Ministry of Culture and plays an important role regarding the safety and protection of the heritage. The TPC is renowned for its efforts and works with law enforcement agencies around the world to recover stolen and illicitly exported artifacts, assists in heritage protection and management globally, recovers stolen art within Italy and abroad, and works to monitor and regulate the art market for looted or illicitly removed art and antiquities.

The TPC has had tremendous success over the decades, recovering hundreds of thousands of objects worth billions of dollars. In a thrilling recent escapade during 2020, the TPC tracked down a 500-year-old painting stolen from a museum in Naples. Jesus Christ in his “Savior of the World” (Salvator Mundi) aspect. The work is a copy of the infamous Salvator Mundi that sold for over $450 million in 2017 (considered the world’s highest-selling painting to date). The police found this copy stashed in the cupboard of an apartment and arrested the 36-year-old property owner. It was probably easy to spot among the inhabitant’s mismatched cutlery.

Castel Sant’Angelo (Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh)

The elite and highly specialized force has celebrated its successes in countless repatriation ceremonies and with art exhibitions. In particular, 2009 marked one of the most high-profile returns resulting from TPC investigations. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (the “Met”) returned the Euphronios Krater (infamously known as the “Hot Pot”) to Italy once the TPC and Swiss authorities uncovered an extensive looting network selling black market antiquities from Italy. These objects wound up in the hands of reputable collectors and museums, including the Met, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum, Harvard University, and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In the wake of this return, hundreds of other items from that network were returned. These restituted works were exhibited in the Colosseum with much pomp, circumstance, and celebration.

At the United Nations in January 2020

A decade later, in 2019, in honor of the TPC’s 50 anniversary, the Carabinieri, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, and the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities organized a comprehensive exhibition of recovered art. “Recovered Treasures: the Art of Saving Art” was on view in Paris and then displayed at the United Nations in New York in January 2020. Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, was invited to attend this exclusive event to open this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition. At the opening, Secretary-General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres aptly stated that the “exhibition not only comprises priceless works of art, it also paints a picture of the power of international cooperation.”

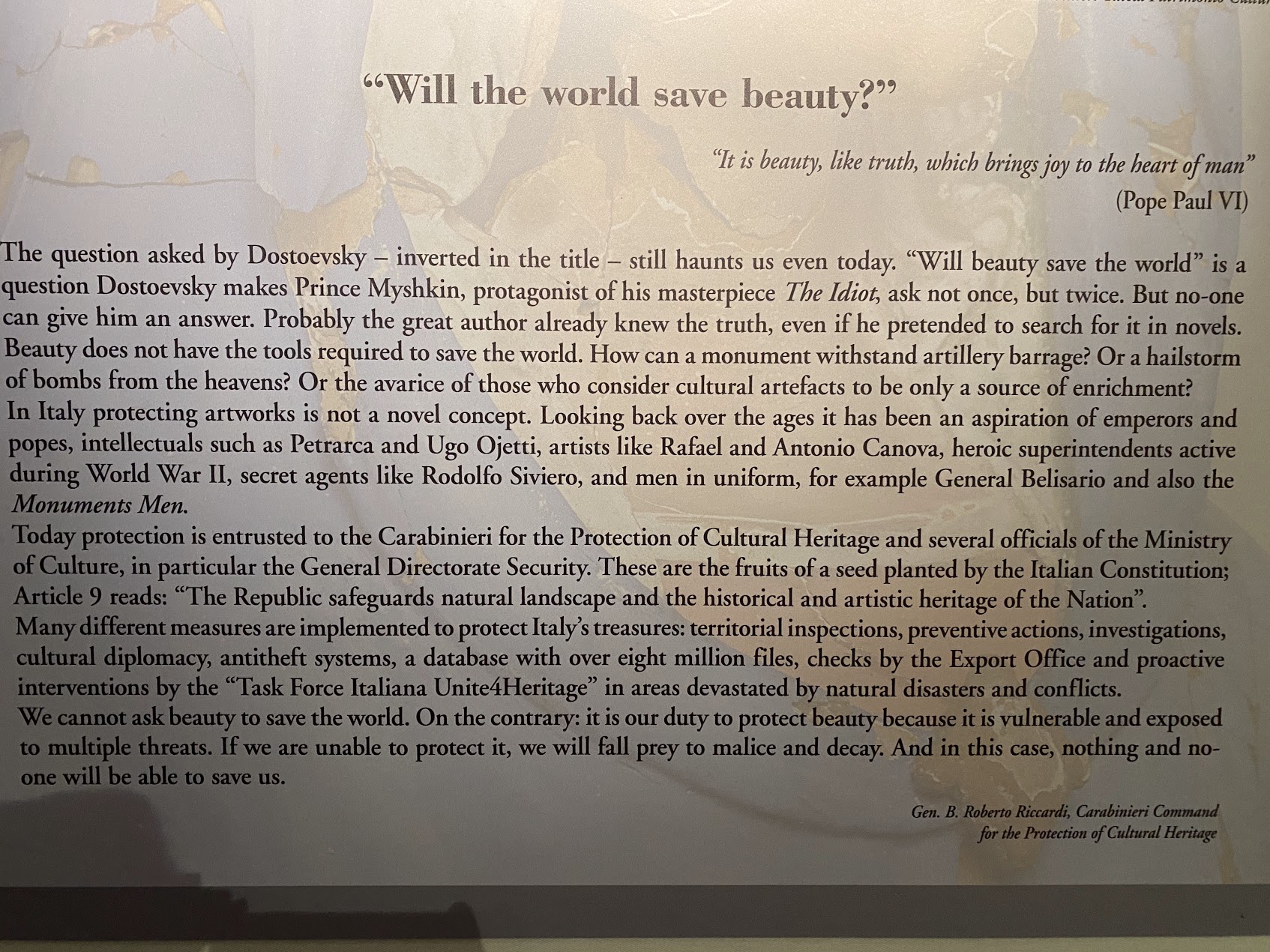

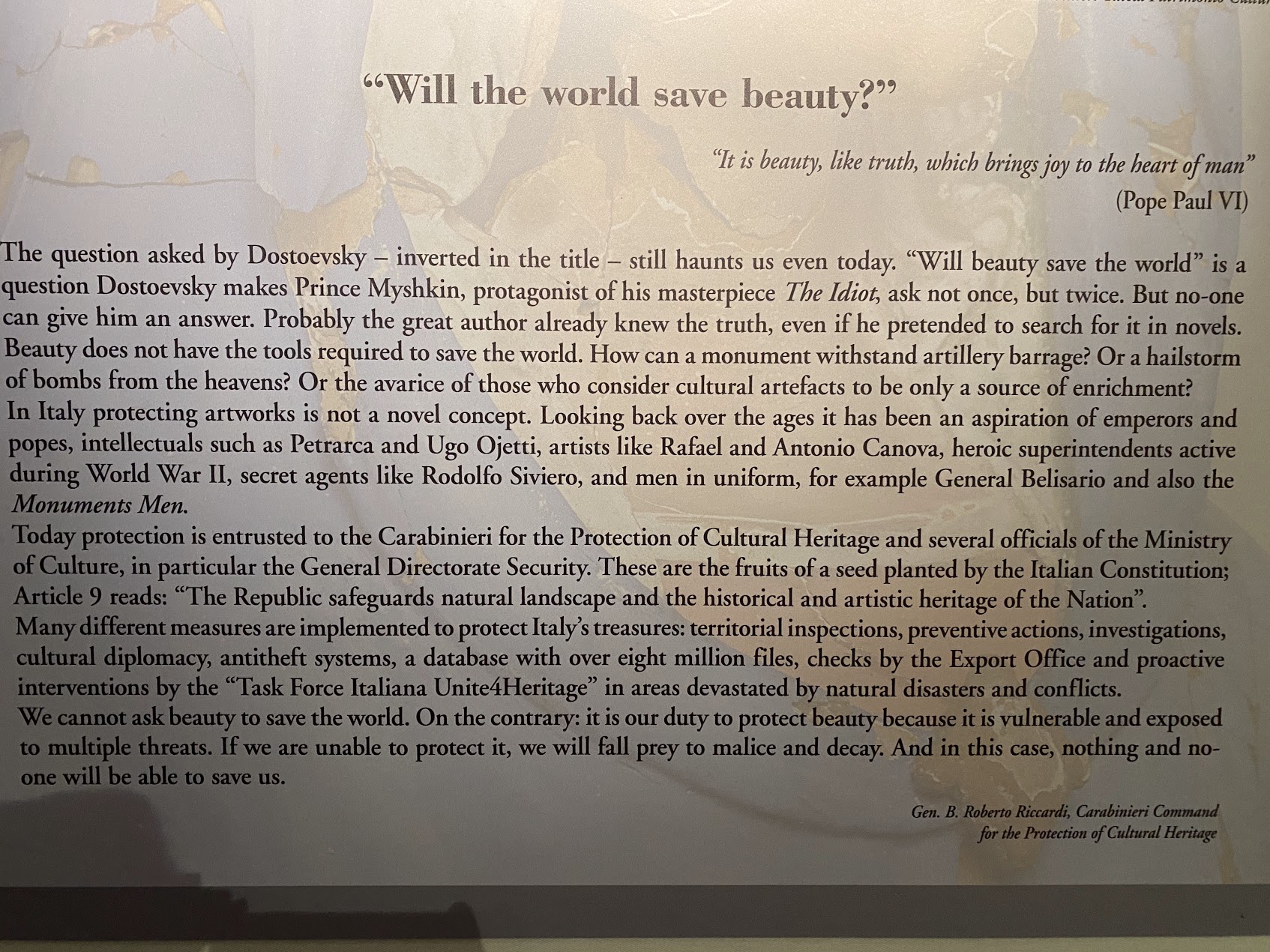

Sign at the entry of “Will the world save beauty?” exhibition

When Italian museums finally reopened after the Covid pandemic, the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome hosted an exhibition entitled “Will the World Save Beauty?,” a show dedicated to exhibited repatriated antiquities, items recovered after natural disasters, works stolen from churches and private institutions, the prevalence of forgeries, and even stolen instruments. Leila also received an invitation from the Carabinieri to view this jaw-dropping show. The juxtaposition of recovered antiquities in a building with nearly 2,000 years of history was both ethereal and moving. This historic site had survived sacking and plundering, and so it was particularly effective to experience repatriated artwork in such a historically rich setting.

Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh

At the start of this summer, Minister of Culture Dario Franceschini announced the opening of the Museo dell’Arte Salvata (“Museum for Rescued Art”), a new museum displaying looted works returned to the Mediterranean nation. The concept for this museum is innovative and appealing – hundreds of smuggled, and now repatriated, artworks will be displayed for public view. But the particular items on display will rotate, with the next group of pieces to be presented after October 15, 2022. Once the displayed works are removed, they will be returned to the respective regions of Italy from where they were originally stolen. The museum’s noble aim is to return objects to the collections of small museums that have suffered from the loss of artwork, giving them and the nation of Italy as a whole a boost to aid in post-pandemic recovery for the culture sector.

Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh

Our founder had the pleasure of visiting the museum shortly after its fabulous opening. The museum is intimate (the objects are all displayed in one large room), and the exhibition is excellent. The repatriated objects on display are organized in glass vitrines featuring information about the works’ significance, the ways in which they were smuggled, and the importance of repatriation. The museum notes that the objects on display are “mainly from the United States of America.” The United States (in particular, New York) is the center of the art market and so items are sold both legally on the market and illicitly. But US authorities have also been instrumental in recovering stolen and illicitly exported objects linked to Italy.

Franceschini stated: “Stolen works of art and archaeological relics that are dispersed, sold or exported illegally is a significant loss for the cultural heritage of the country…. Protecting and promoting these treasures is an institutional duty, but also a moral commitment: it is necessary to take on this responsibility for future generations.” Stéphane Verger, director of the National Roman Museum, poignantly noted: “I think of this as a museum of wounded art, because the works exhibited here have been deprived of their contexts of discovery and belonging.”

Just a month after this exhibition’s opening, another 142 Italian antiquities seized by the Manhattan DA are headed home to Italy. This included 48 items recovered from private collector Michael Steinhardt during a high-profile seizure in December 2021, where the former hedge fund manager agreed to surrender $70 million worth of antiquities. The most valuable work returned to Italy is a fresco depicting an infant Hercules strangling a snake, valued at $1 million and looted from Herculaneum. Officials revealed that another 60 of the items were recovered from Royal-Athena Galleries in Manhattan.

Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh

As this law firm is currently representing the Republic of Italy in an ongoing antiquities dispute, and our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert for the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office regarding the seizure of items from Michael Steinhardt, traveling to Rome and visiting such an impressive and important exhibition was – in Ms. Amineddoleh’s word – both powerful and gratifying. This highlights the impact of cultural heritage looting and trafficking at the global level and close to home.

The Museo dell’Arte Salvata is located in the Aula Ottagona, a building that had previously been closed for a number of years. The structure is part of the Baths of Diocletian complex, located a few minutes away from Termini Train Station (Rome’s main railway station), and across the street from the Repubblica subway station, in the heart of the Eternal City. Since it is part of the network of national Roman museums, visitors can purchase one ticket and see all five museums for one relatively inexpensive entry price. It is well worth the trip – and visitors can wrap up their visit with a large bowl of cacio e pepe and a hearty glass of Chianti Classico for a true Italian experience.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4