by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Aug 23, 2020 |

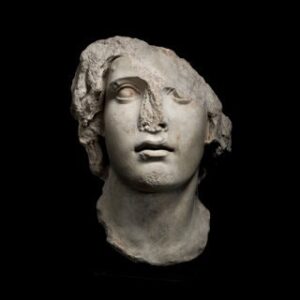

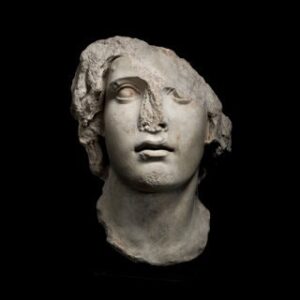

Last week, Amineddoleh & Associates LLC filed its second Motion to Dismiss in the case of Safani Gallery, Inc. v. The Italian Republic, Civil No. 19-10507 (SDNY), responding to Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint. Here, Plaintiff – an antiquities gallery –seeks redress from Italy for the seizure of a marble antiquity depicting a male bust. The seizure was made by the Manhattan District Attorney, not the Mediterranean republic. The object first gained public attention in 2018 when it was reported by the NY Times that the Manhattan DA seized the object described by the plaintiff art gallery as the “Head of Alexander.” This is a misnomer, as the marble likely depicts a Parthian “barbarian.” A filing by the DA in NY State Supreme Court describes the head as one that decorated the Basilica Emilia, a civil basilica in the heart of the Roman Forum. For information about the Basilica Emilia, the American Institute for Roman Culture’s onsite video offers a glimpse of the important historic site. (Ironically, one of the functions of the Basilica Emilia was as a law court.)

Last week, Amineddoleh & Associates LLC filed its second Motion to Dismiss in the case of Safani Gallery, Inc. v. The Italian Republic, Civil No. 19-10507 (SDNY), responding to Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint. Here, Plaintiff – an antiquities gallery –seeks redress from Italy for the seizure of a marble antiquity depicting a male bust. The seizure was made by the Manhattan District Attorney, not the Mediterranean republic. The object first gained public attention in 2018 when it was reported by the NY Times that the Manhattan DA seized the object described by the plaintiff art gallery as the “Head of Alexander.” This is a misnomer, as the marble likely depicts a Parthian “barbarian.” A filing by the DA in NY State Supreme Court describes the head as one that decorated the Basilica Emilia, a civil basilica in the heart of the Roman Forum. For information about the Basilica Emilia, the American Institute for Roman Culture’s onsite video offers a glimpse of the important historic site. (Ironically, one of the functions of the Basilica Emilia was as a law court.)

Ruins of Basilica Emilia Photo credit: @Roma_Wonder

Notably, this case bears certain similarities to the Barnet litigation, where our firm represented the Greek Ministry of Culture and recently secured a favorable decision in the Second Circuit. As in Barnet, here a foreign sovereign made a communication concerning an antiquity originating from within its borders. However, in Safani, a tip was made to U.S. law enforcement (the Manhattan DA) rather than to a private party. While the original Complaint focused on jurisdiction under the commercial activity exception of the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act (FSIA), the Amended Complaint altered its allegations to include the FSIA’s tort exception, expropriation exception and obligations under several international legal instruments. We are confident that the court will correctly interpret the FSIA’s exceptions. We are proud to represent Italy in this matter, particularly as the nation’s record for protecting cultural heritage has gained it international praise. As the nation with the most number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites (Italy boasts 55), our client actively protects its heritage for current and future generations.

Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to continue representing clients in high-profile antiquities cases which affect the international protection of heritage.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 20, 2020 |

For decades, art institutions have struggled to find a compelling response to concerns raised over owning and possessing art and antiquities taken and exported during periods of colonialism. Critics argue that it is unethical to continue holding works that were sourced during times of conflict or subjugation, and often taken as trophies of war or as symbols of power over foreign subjects. By doing so, it deprives the original owners of their rights. Critics also argue that displaying these objects in a foreign museum strips them of essential cultural context. While the debate over such works is nothing new (nations such as Greece, Egypt, India and China have been seeking repatriation of objects for decades), recent protests against racial injustice across the globe have brought the conversation out of museum boardrooms and into the spotlight.

One of the Benin Bronzes at the British Museum. Copyright: British Museum

As museums across Europe begin to reopen, Dan Hicks, a professor and senior curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, has begun the arduous tasking of evaluating the museum’s collection of more than 600,000 works representing almost every country across the globe. Hicks acknowledges that displaying works of cultural significance without proper context risks telling a revisionist version of history. The professor has received acclaim for his efforts to re-introduce the museum’s collection to the public from the perspective of the works’ countries of origin. “This is very specifically about a period of time when our anthropology museums were used for purposes of institutional racism, race science, the display of white supremacy. At this moment in history, it could not be more urgent to remove such icons from our institutions.” Hicks also believes in deaccessioning and returning works that were illicitly seized, including notable objects such as the Benin Bronzes. The bronzes, which are found in many prominent museums around the world, were seized by British soldiers during a punitive raid on the Kingdom of Benin in 1897 (modern day Nigeria). To Hicks, the decision is simple: “It is a matter of respect and being treated equally. If you steal people’s heritage, you’re stealing their psychology, and you need to return it.” It remains to be seen whether museums will adopt this approach as the public continues applying pressure on museums to reconcile with a troubling past.

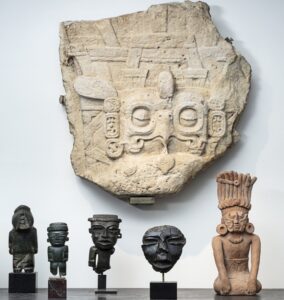

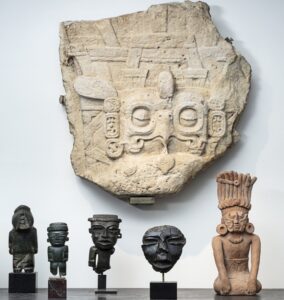

The large carved relief showing a Maya king’s headdress with an owl motif is among works to be sold at auction in Paris. Copyright: Millon and Assoc.

It is important to note that this problem is not exclusive to European countries with an imperialistic past; culturally significant works are still being looted and sold on the open market today. In particular, works from Africa and South America are becoming increasingly popular among art collectors, bringing stolen or looted works to the surface of the market. Amineddoleh & Associates LLC recently discussed two such works which were sold at auction in Paris despite claims that they were looted in violation of local law. In contrast, another French auction house recently pulled a Mayan sculpture from its sale after allegations that the piece was clearly stolen spurred public outcry. Archeologists had previously documented the piece at the ancient city of Piedras Negras, in modern day Guatemala, placing its export during the 1960s and virtually eliminating the possibility that it was exported legally. The Guatemalan Embassy in Paris released a statement once it was agreed the work would be withdrawn stating that negotiations with the sellers were underway. The close proximity of these two sales with different outcomes demonstrates that countries have not yet determined a reliable means of repatriating looted artwork. The significance of this issue was underscored recently as an Interpol sting led to the seizure of approximately 19,000 stolen artifacts, including pre-Columbian relics, suggesting the illicit market for such goods is thriving. In fact, just last year a French auction house sold dozens of Mexican artifacts, despite Mexico’s demand for their return. Hopefully, countries will find it easier to have culturally significant works returned as the public becomes more aware of the issue and ask institutions to be held accountable.

Collectors must also be aware that purchases of cultural artifacts may be legal at the time of sale, but subject to scrutiny and criticism later on. It is imperative to consult knowledgeable professionals before adding potentially questionable items to a collection, whether public or private. Amineddoleh & Associates prides itself on its knowledge of the art and cultural heritage market, and we assist collectors and purchasers in carrying out responsible transactions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 14, 2020 |

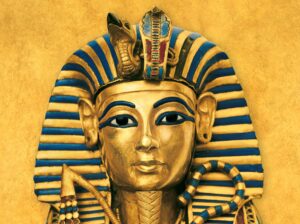

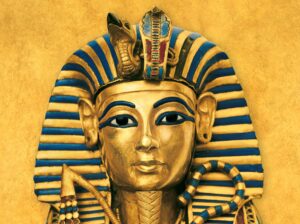

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, was interviewed by Turkish news channel, TRT, to discuss a controversial international exhibition of objects from the tomb of Egypt’s famed King Tutankhamen. (A video of the interview is below.) The discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 sparked a resurgence in the interest in ancient Egypt. Any exhibition related to his remains and treasures is sure to attract huge revenue and worldwide attention. The exhibition, Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh, features 150 objects owned by Egypt.

Nations enact cultural heritage laws to protect their heritage for the benefit of their citizens, future generations, and all mankind. Artifacts have a value greater than their commercial prices, and it is the responsibility of nations to protect these resources. In fact, Egypt has some of the world’s oldest laws protecting antiquities and regulating their trade. Egyptian antiquities have long been a source of fascination for Western collectors. Due to that market interest, Egypt has protected its artifacts with legal tools. The nation actively safeguards its antiquities with cultural heritage protection laws dating back nearly two centuries. The first law, an 1835 decree, banned the unauthorized removal of antiquities from the country. During the intervening nearly two centuries, the nation has periodically updated those laws to effectively protect ancient sites and prevent looting.

The Supreme Council of Antiquities (Egypt’s cultural ministry) may have broken the nation’s cultural heritage laws by engaging a private commercial company, IMG, to exhibit valuable artifacts in shows around the world. However, there are some vague terms in Egypt’s cultural heritage law that might make it difficult for an Egyptian lawyer to successfully sue the Supreme Council. (For example, the law does not define what makes certain artifacts “unique” and prohibited from loans.)

It is easy to understand how some Egyptians feel betrayed by the Supreme Council. The nation’s rich cultural heritage was not intended to be exploited by government officials for their own personal use or financial gain. The nation’s antiquities play a central role in its citizens’ identities and the identity of Egypt. Some Egyptians feel that artifacts from King Tut’s tomb are a national treasure and so they should not be touring internationally, but should remain in Egypt, their home. The Arab republic’s cultural heritage laws were passed with the purpose of protecting heritage for future generations and to protect the property from exploitation and destruction. In fact, the introduction (written by Zahi Hawass) of the 2010 amendment to Law 117 addresses the importance of heritage protection for the “honor of Egypt and Egyptian history.” It also states, “The memory of the homeland is the right of future generations, and our duty to them is to keep this memory alive and vibrant.”

Copyright: National Geographic

Whereas the Egyptian government touts the value of the international exhibition, stating that it has brought in millions of dollars to the country, there is potential harm. The objects from the exhibition will not be back in Egypt in time for the monumental opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum (a $1 billion project), and the exhibit may divert tourism revenue away from Egypt and instead to the commercial exhibition company, IMG. In addition, any international exhibition is accompanied by risks inherent in traveling and reinstallation.

Various elements addressed in the BBC documentary about the exhibition seem to suggest that the loan is the result of political corruption, with former and current members of the Supreme Council of Antiquities receiving financial benefits by agreeing to the loan. Private companies have hired former and current members of the Supreme Council to serve as tour guides, sell products, and engage in commercial activity related to Egyptian antiquities. The current exhibition schedule is indefinitely delayed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it will be interesting to see how the controversy is resolved and whether the artifacts from the “Boy King” will return home in time for the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 6, 2020 |

Readers may recall from a previous blog post that Facebook Marketplace has become the subject of criticism for playing host to antiquities traffickers selling looted cultural heritage items online. Employing Facebook’s sophisticated algorithms, traffickers quickly connect with buyers receptive to purchasing plundered goods or with less experienced buyers who do not recognize the red flags associated with looted antiquities. Red flags include an origin from a conflict zone (such as Syria or Iraq), lack of provenance or export documents, and comparatively low prices in relation to the object’s scarcity or true value. Online sales have flourished after the looting of cultural heritage sites during and after the Arab Spring, and illicit trafficking of antiquities has been recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has left many cultural heritage sites defenseless and ripe for plunder. Antiquities as varied as scrolls, coins, and even mummified human remains are sold through online groups. More troubling is the fact that members would discuss how to illegally excavate historical sites. Some members provide tips on how to avoid law enforcement officials, while others make specific “loot to order” requests, deliberately targeting specific objects. The smuggling of Middle Eastern antiquities has been linked to terrorist groups and other crime syndicates. While physical border security may be tightened, it is more difficult to tackle online transactions.

As a result, groups like the ATHAR Project have been demanding changes. “Athar” is the Arabic word for antiquities, but the name also stands for “Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research.” Co-Directors Prof. Amr Al-Azm and Katie A. Paul have dedicated the project to ascertaining relationships between the digital underworld, transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The founders have spoken to media outlets to assist investigations into the issue. In response to this outcry, Facebook announced a change in policy to ban from its marketplace any “content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts.” The change was made effective as of June 23, 2020.

As a result, groups like the ATHAR Project have been demanding changes. “Athar” is the Arabic word for antiquities, but the name also stands for “Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research.” Co-Directors Prof. Amr Al-Azm and Katie A. Paul have dedicated the project to ascertaining relationships between the digital underworld, transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The founders have spoken to media outlets to assist investigations into the issue. In response to this outcry, Facebook announced a change in policy to ban from its marketplace any “content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts.” The change was made effective as of June 23, 2020.

Although the ban is an encouraging step towards the eradication of antiquities trafficking, Facebook’s decision is indicative of a larger problem facing the art market: the move to online sales spurred by developments in technology, and more recently the pandemic, has rendered the market more vulnerable to traffickers selling loot. Closing the Facebook Marketplace to “historical artifacts” is perhaps a well-intentioned gesture, but it fails to adequately address the concerns in the larger market. An expert was quoted as suggesting that Facebook should invest in specialized teams to identify and remove criminal networks at their source rather than “playing whack-a-mole with individual posts.”

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately, our client was victorious in defending itself against jurisdiction in the U.S.

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately, our client was victorious in defending itself against jurisdiction in the U.S.

On its face, banning cultural heritage items from Facebook Marketplace appears to be a responsible choice. In truth, Facebook is relegating a problem that it helped foster to nations that are already struggling to police the market. Critics of the ban argue that Facebook’s role in the illicit market makes the works more visible and easier for countries to locate. By closing its doors, Facebook has likely pushed these sales deeper into the black market, making them more difficult to track and recover. Further, Facebook indicated that it will not preserve information associated with the sale of artifacts, citing privacy concerns. This means that any information on the site will be destroyed rather than shared with countries of origin. Noting that “theft, pillage or misappropriation of” cultural property violates international law and constitutes a war crime, critics assert that social media evidence has been used by the International Criminal Court to prosecute and convict war criminals as recently as 2017. Facebook is ready to wash its hands of the market for looted antiquities, but in doing so, is neglecting the possibility of using its already established position to counteract the presence of looting on a more effective and direct basis.

The wooden sculptures, one male and one female, represent deities from the Igbo community. Copyright: Christie’s

Facebook is not alone in playing a troubling role in the illicit market. Whereas some traffickers exploit the dark recesses of the internet, others turn to the its most prominent levels in an attempt to legitimize a looted artwork. Due diligence measures have slipped during the COVID-19 pandemic, as buyers and intermediaries have been unable to inspect works personally. Recently, Christie’s was called upon by a prominent art historian to pull two Nigerian statues from a sale in Paris, believing the works were looted during civil war in the 1960s. At the very least, more information would be necessary to determine if the works had been exported illegally. Yet despite these concerns, Christie’s proceeded with the auction. Defending the sale, Christie’s maintained that there wasn’t “any suggestion that these statues were subject to improper export,” prior to the academic’s request. Unfortunately, this response side-steps an inconvenient truth that doubts about provenance may only surface once a work enters the global spotlight, as in an auction house sale. For instance, the lack of prior ownership claims may be due to the item being held in a private collection prior to sale. An official for the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments said he “was saddened” by the sale, but the country has not yet made a formal demand for repatriation. Despite the controversy, and perhaps encouraged by the lack of action by Nigeria, the piece sold for just under $240,000 (£195,000). Only time will tell whether the statues become the subject of litigation.

It is important for collectors to understand the particularities of acquiring antiquities, and it is important consult knowledgeable professionals to avoid problems. Amineddoleh & Associates has a wealth of experience addressing the challenges faced by foreign nations and private owners. Our founder has served as an expert for a number of high-profile repatriations. (She served as a cultural heritage law consultant in the return of thousands of looted artifacts to Iraq in the “Hobby Lobby” forfeiture, and as a cultural heritage law expert in matters such as the return of an Achaemenid relief to Iran, a golden coffin and mummy parts to Egypt, and a mosaic from one of Caligula’s ships to Italy.) This firm has represented museums, foreign nations, collectors, and sellers in litigations and transactional matters. Moreover, we routinely aid our clients in conducting due diligence to ensure that their purchases are legally permitted and free from encumbrance. As the pandemic continues and online cases soar, savvy purchasers must be as cautious as possible and contact legal counsel familiar with the art market’s pitfalls.

Last week, Amineddoleh & Associates LLC filed its second Motion to Dismiss in the case of Safani Gallery, Inc. v. The Italian Republic, Civil No. 19-10507 (SDNY), responding to Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint. Here, Plaintiff – an antiquities gallery –seeks redress from Italy for the seizure of a marble antiquity depicting a male bust. The seizure was made by the Manhattan District Attorney, not the Mediterranean republic. The object first gained public attention in 2018 when

Last week, Amineddoleh & Associates LLC filed its second Motion to Dismiss in the case of Safani Gallery, Inc. v. The Italian Republic, Civil No. 19-10507 (SDNY), responding to Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint. Here, Plaintiff – an antiquities gallery –seeks redress from Italy for the seizure of a marble antiquity depicting a male bust. The seizure was made by the Manhattan District Attorney, not the Mediterranean republic. The object first gained public attention in 2018 when

As a result, groups like the

As a result, groups like the  As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately,

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately,