For decades, art institutions have struggled to find a compelling response to concerns raised over owning and possessing art and antiquities taken and exported during periods of colonialism. Critics argue that it is unethical to continue holding works that were sourced during times of conflict or subjugation, and often taken as trophies of war or as symbols of power over foreign subjects. By doing so, it deprives the original owners of their rights. Critics also argue that displaying these objects in a foreign museum strips them of essential cultural context. While the debate over such works is nothing new (nations such as Greece, Egypt, India and China have been seeking repatriation of objects for decades), recent protests against racial injustice across the globe have brought the conversation out of museum boardrooms and into the spotlight.

One of the Benin Bronzes at the British Museum. Copyright: British Museum

As museums across Europe begin to reopen, Dan Hicks, a professor and senior curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, has begun the arduous tasking of evaluating the museum’s collection of more than 600,000 works representing almost every country across the globe. Hicks acknowledges that displaying works of cultural significance without proper context risks telling a revisionist version of history. The professor has received acclaim for his efforts to re-introduce the museum’s collection to the public from the perspective of the works’ countries of origin. “This is very specifically about a period of time when our anthropology museums were used for purposes of institutional racism, race science, the display of white supremacy. At this moment in history, it could not be more urgent to remove such icons from our institutions.” Hicks also believes in deaccessioning and returning works that were illicitly seized, including notable objects such as the Benin Bronzes. The bronzes, which are found in many prominent museums around the world, were seized by British soldiers during a punitive raid on the Kingdom of Benin in 1897 (modern day Nigeria). To Hicks, the decision is simple: “It is a matter of respect and being treated equally. If you steal people’s heritage, you’re stealing their psychology, and you need to return it.” It remains to be seen whether museums will adopt this approach as the public continues applying pressure on museums to reconcile with a troubling past.

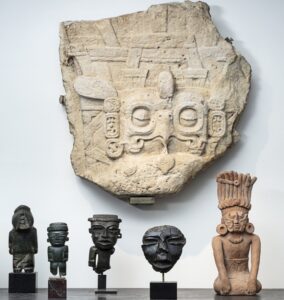

The large carved relief showing a Maya king’s headdress with an owl motif is among works to be sold at auction in Paris. Copyright: Millon and Assoc.

It is important to note that this problem is not exclusive to European countries with an imperialistic past; culturally significant works are still being looted and sold on the open market today. In particular, works from Africa and South America are becoming increasingly popular among art collectors, bringing stolen or looted works to the surface of the market. Amineddoleh & Associates LLC recently discussed two such works which were sold at auction in Paris despite claims that they were looted in violation of local law. In contrast, another French auction house recently pulled a Mayan sculpture from its sale after allegations that the piece was clearly stolen spurred public outcry. Archeologists had previously documented the piece at the ancient city of Piedras Negras, in modern day Guatemala, placing its export during the 1960s and virtually eliminating the possibility that it was exported legally. The Guatemalan Embassy in Paris released a statement once it was agreed the work would be withdrawn stating that negotiations with the sellers were underway. The close proximity of these two sales with different outcomes demonstrates that countries have not yet determined a reliable means of repatriating looted artwork. The significance of this issue was underscored recently as an Interpol sting led to the seizure of approximately 19,000 stolen artifacts, including pre-Columbian relics, suggesting the illicit market for such goods is thriving. In fact, just last year a French auction house sold dozens of Mexican artifacts, despite Mexico’s demand for their return. Hopefully, countries will find it easier to have culturally significant works returned as the public becomes more aware of the issue and ask institutions to be held accountable.

Collectors must also be aware that purchases of cultural artifacts may be legal at the time of sale, but subject to scrutiny and criticism later on. It is imperative to consult knowledgeable professionals before adding potentially questionable items to a collection, whether public or private. Amineddoleh & Associates prides itself on its knowledge of the art and cultural heritage market, and we assist collectors and purchasers in carrying out responsible transactions.