by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 24, 2023 |

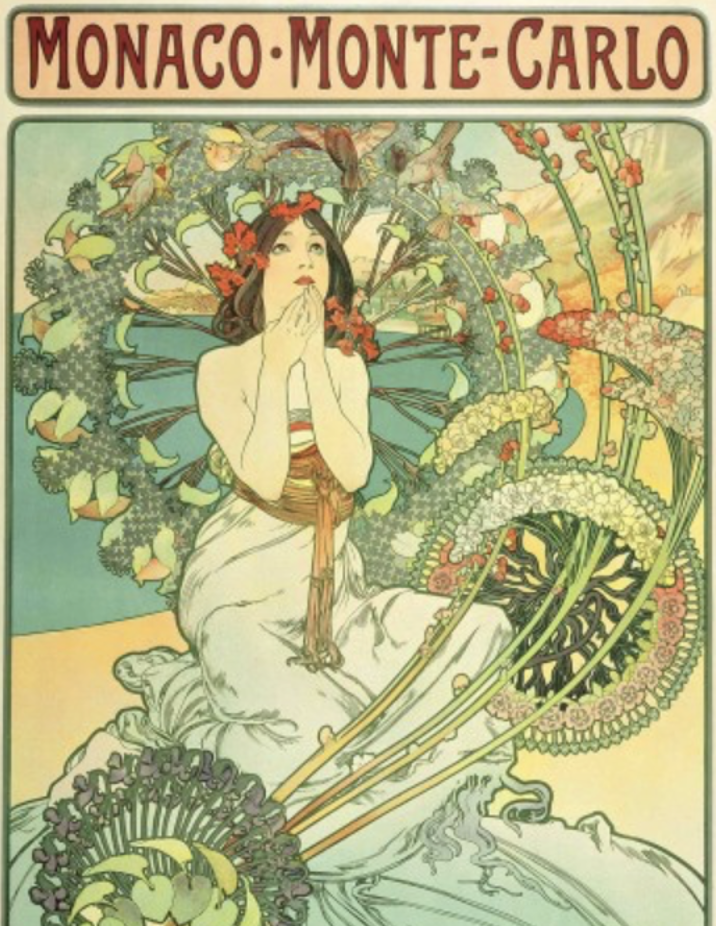

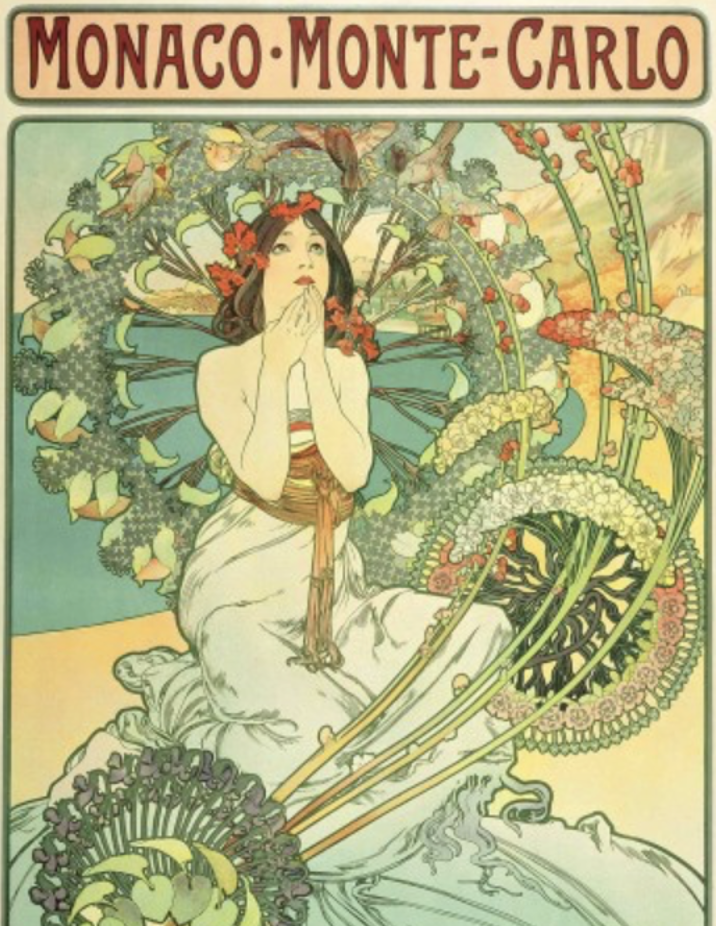

Art Nouveau fans rejoice: July 24th is the late Alphonse Mucha’s birthday. This year’s anniversary comes with a bit less fanfare than his 150th in 2010, when Google created a doodle on the artist’s behalf.

But even without a doodle from Google, Mucha’s legacy continues to influence art and artists around the world. One aspect of his enduring legacy is how his work influenced the rise of celebrity art. This phenomenon has been popping up more and more frequently in American culture, and no one (not even celebrities themselves) are immune from the draw of star power.

Modern Celebrities Embrace Art

No longer playing the role of pirate, actor Johnny Depp has swapped his sword for a paintbrush in real-life. It seems to have been a sound business move. The actor made a staggering $3.6 million selling works from his first “Friends & Heroes” art collection in 2022. His second, entitled “Friends & Heroes II” was released in February. It is comprised of four portraits of artists that have inspired Depp throughout his life: Bob Marley, Health Ledger, River Phoenix, and Hunter S. Thompson. An unbelievable answer to the classic “Dream guests at a dinner party?” question, if ever one existed. Almost already entirely sold out – all that remains on the Castle Fine Art website is a pack of all four prints, priced at a swashbuckling $20,416.67.

Depp’s foray into celebrity art highlights modern culture’s fascination with all-things celebrity. Are Depp’s works prized due to his creative talent as an artist? Or are the pieces selling because they are exclusively of famous celebrities? Or, possibly, Depp is able to sell out faster than Taylor Swift tickets because he, himself, is a celebrity? Which points to the threshold question: when did artists begin to feature celebrities in art? Many art historians look no further than the incredibly gifted Alphonse Mucha, who skyrocketed his own career to greater heights through his collaboration with a famous actress.

Rise of Celebrity Art

“If you have to explain to someone you’re famous, then you’re technically not that famous.”- David Spade.

The beauty of Alphonse Mucha‘s work stems from his deep passion as an artist. Many artists are known for having a lot of gusto, but Mucha really takes the cake. He was master of the Art Nouveau style of art, so masterful in fact that many credit his career for influencing major tenants of the age – politics, religion, philosophy, and – of all things – the career of one very famous actress named Sarah Bernhardt.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ‘La Plume’ magazine (1897). Image via muchafoundation.org.

Before we get to Sarah, a little more about our man Mucha. He was born on July 24, 1860, in a quiet town in Moravia. In his youth, Mucha was – in his own words – “preoccupied with observing.” This tendency to notice things around him manifested in a profound artistic talent. Young Mucha could be found making sketches and drawings for friends, family, and fellow townsfolk. His drawings were so prodigious that he collected quite a few fans, even in his early days. One fan was the town’s shopkeeper, who often slipped Mucha free sheets of a paper – a luxury of the day – in order for him to make his creations.

As Mucha grew older, his artistic talent also matured. When he was 18, he was ready to apply to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. Unfortunately, he was rejected. The admissions office even went as far to suggest he take up a different, “less artistic” career. I’m not sure what they had in mind (medical school?), but fortunately for us, Mucha was not discouraged for long. He decided to simply carry on and continued to make art in whatever way he could.

A year later, Mucha had a bit of luck – an opportunity arose for an artist to work with a Vienna newspaper making advertisements. The pay was pitiful, and Vienna is freezing cold in winter. However, Mucha forged ahead, desperate to create. He applied, scored the gig, and packed his bags for his journey to the big city.

This was a turning point in Mucha’s development as an artist. He spent two years in Vienna, creating advertisements for the paper by day and taking art classes by night. What this did was cement in him a love for creating artwork that was accessible to the average, everyday person. He thrived on creating beauty in pamphlets, posters, and advertisements that most companies and institutions did not have the time or talent to make elaborate. We can start to see, from this period, the development of certain curvature in his lines, and repetition of old world-inspired motifs come up again and again in works that would inevitably become a part of an ordinary person’s daily life.

Mucha retained this love of creating beautiful and accessible work, while still seeking to enhance his skill as an artist through more formal training. Eventually, he applied to – and was accepted to enroll in – the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in September of 1885. This provided Mucha with formal artistic skills, though it is important to note that Mucha is still believed to be largely self-taught as an artist (which could also mean that he ignored much of what was taught in school). From Munich, he made his way to Paris: the art capital of the world at the time.

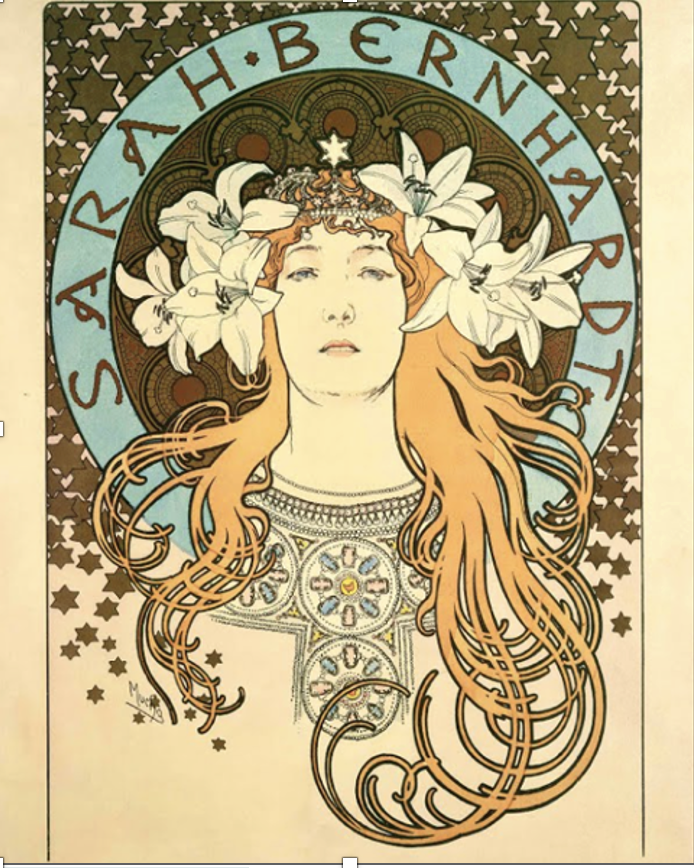

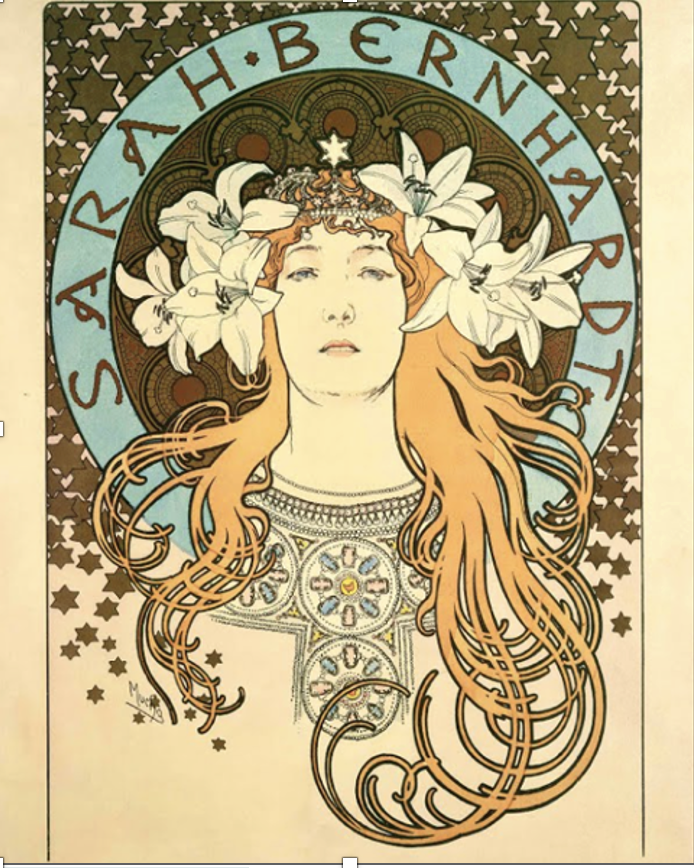

In the City of Lights, he established himself as a “reliable” illustrator (as noted by his biographers). The Paris theater scene is where the lives of Mucha and the phenom Sarah Bernhardt intersect. Sarah Bernhardt is often touted as the original “true superstar.” This is before the current fame-cycle of Hollywood starlets, who now can be seen as a dime a dozen, splashed across the covers of People magazine.

Sarah Bernhardt was the real-deal – a woman with the poise, charisma, and gumption to make a name for herself as an actress against the backdrop of a politically tumultuous city. Not only is she remembered as a strikingly impactful actress, known for her talent, she is also regarded as the first superstar known to personally exploit her own image and likeness for economic gain, and to raise her own fame. This is an important piece of the puzzle of a topic referred to as “publicity,” which we’ll address later.

Mucha began working with Bernhardt in December 1894, in a serendipitous sort of meeting that can only be attributed to fate. Bernhardt’s play, Gismonda, was set to open on January 4th, 1895. On December 26th, 1894 – just a few short days before opening night – the starlet decided that her show needed a new poster to publicize the play. Something dazzling. Something that would leave Paris speechless.

She turned to the manager of a Parisian printing firm for a new poster, pronto. Given the short notice, and the fact that Bernhardt approached the firm in the middle of the Christmas break, Maurice was short on options for the commission. In desperation, he turned to Mucha – truly the only option at hand – and begged him to take on the job. Ever the flexible type, Mucha agreed. And, in doing so, a true collaboration between two legendary artists was born.

The success of Mucha and Bernhardt’s eventual career-long collaboration is likely because the two saw eye-to-eye on Sarah’s talent.

Alphonse Mucha, Poster for ’Gismonda’ (1894). Image via muchafoundation.org.

In other words, Mucha was a fan. In creating the poster for Gismonda, he relied on his personal knowledge of the play itself, as well as his fascination with how Bernhardt depicted the title role. The result? A stunningly ethereal piece that focused the viewer of the poster on the actress herself, rather than on fussy knickknacks in the background. The poster was truly a spotlight on Sarah, in all her glory – and Sarah loved it.

Thus, the two kicked off a mutually beneficial partnership. Bernhardt became Mucha’s artistic muse and mentor in the industry. They also became very good friends. Each seemed impressed by the other’s commitment to creativity, and fervent refusal to be fenced in by artistic norms of the day. Sarah, for her part, pushed the boundaries of Parisian theater by lobbying for politically impactful roles. Mucha, on his end, blazed a trail as a high-end artist for the lower strata of society.

Much of the work Mucha did for Sarah was accessible to the everyday Parisian, because her giant posters were displayed on the street. And, he created many posters of Bernhardt in her various roles throughout the remainder of her career. Because Mucha continued to make Bernhardt the star of each new poster, his work served to elevate her career to even greater heights. In this way, Bernhardt was able to exploit her own image and likeness to increase her status as a public figure – and was one of the first known celebrities to ever do so.

The upside for Mucha was that, because of his work that featured Sarah, he became higher-in-demand as an artist for other jobs. Mucha became more famous and earned more money because he painted someone famous.

Collaboration v. Exploitation

Mucha’s portrayals of Sarah Bernhardt in his artwork were clearly a collaboration. But, using a celebrity’s image in a work of art does bring forth a question: when can an artist legally make use of a person’s image or likeness in a work of art, if use of that image increases the economic value of the work itself?

Modern Legal Framework & Application

To answer this question, two rights come into play. Both come from state, rather than federal law, and are mostly understood through case law.

The first right is called the right of privacy. This means is that private people have the right to prevent the public disclosure of their name and likeness by others. For example, if a company started using a private person’s face as the logo for a brand of salad dressing, that person could bring an action against that company claiming the right of privacy.

The second right, which sounds similar, but functions very differently, is called the right of publicity. That right means that a person has the right to exploit her own image and likeness for her own economic gain. Using the salad dressing example, this is why “Newman’s Own” salad dressing uses his face on the label. His company profits from the use of his public image on its products. The right belongs to Newman’s heirs, because the value of his image is the fruit of his own hard work as a famous actor. (Confusingly, what is referred to as the right of privacy in New York is, in fact, the right of publicity).

Sometimes, the aforementioned rules change if, instead of, as in the example, an advertiser using the celebrity’s image, the person using the celebrity’s image is an artist creating a work of art.

Some courts have held that any work created by an artist, even if it uses a celebrity’s image, is a form of free expression. The First Amendment protects free speech. Included in the many categories of free speech is art – it’s speech, even if it doesn’t make noise.

Courts that have broadly interpreted the First Amendment free speech protection in cases where an artist uses a celebrity’s image in their art have generally permitted it. According to these courts, if artist’s use of the celebrity image is a form of free speech, it is allowed. However, the application of this principle is not as straightforward as it might appear. While some courts have given artists broad discretion under the First Amendment to use celebrities in their works, other courts have sided with celebrity defendants, under the theory that the artist’s work violates the celebrity’s right of publicity.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 21, 2023 |

Leila has been recognized by Chambers & Partners for her work in art and cultural property law. Image via Chambers & Partners.

Amineddoleh & Assoc., LLC is proud to announce that our firm’s founder has been listed for the second consecutive year by Chambers & Partners in the latest edition of its High Net Worth Guide for her accomplishments in Art and Cultural Property Law.

Chambers indicated that Leila “is very active in this space and in the litigation area. She has a lot of expertise in the cultural property space. . . a great person in this area.” A source for Chambers went on to say, “She impresses me. She is very practically minded and has a great courtroom manner.”

We are pleased to see our founder recognized in the 2023 HNW Guide rankings for the second consecutive year. These rankings reflect not only the quality of the services our firm provides for our clients, but also our team’s fundamental commitment to providing the highest level of service to our clients.

We extend our sincerest thanks to our clients and colleagues for their confidence in our firm and in recognition of our founder’s work and expertise.

Congrats Leila!

View the ranking below:

Amineddoleh & Assoc., LLC is a premier art law practice based in NYC that advises domestic and international collectors, art dealers, galleries, artists, museums and other cultural institutions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 12, 2023 |

Our client, Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, with his work “Point of Infinity” in San Francisco. Image via Jessica Chou/The New York Times.

Our firm is proud to announce the public art unveiling of the newest sculpture installation from our esteemed client Hiroshi Sugimoto. Entitled Point of Infinity, Sugimoto’s breathtaking sculpture stands as contemplative sentinel over the San Francisco Bay. The stunning work – intended to draw the eye upwards to an indefinite point – is 69-feet of stainless steel construction. Its very physicality relies on Sugimoto’s precise artistic eye and meticulous engineering skills. The sculpture is 23-feet at its base, yet less than one inch across at its top. To construct such a gravify-defying sculpture, while still maintaining the optical illusion that the two points will (eventually, even if only in the viewer’s minds’ eye) meet, reveals the genius of Sugimoto as an artistic force. It is truly an honor to work with him and represent his work.

Sugimoto began this project in 2017, and our firm has been at his side to protect his artistic and intellectual property in the work. Sugimoto won an open call for artists in order to produce the piece. The Treasure Island Art Program selected his work from an astonishing pool of 495 talented artists.

Manhattan Apartment designed by Hiroshi Sugimoto. Image via Anthony Cotsifas/New York Times.

Our firm is thrilled to call attention to the incredible work and expansive lexicon of Sugimoto. His success across multiple mediums speaks to his innate talent, pure vision, and clear artistic voice. Sugimoto is continually producing new, fresh work and drawing upon past experiences to refine and hone his talent.

In 2019, Sugimoto was featured in The New York Times for designing one of T’s Best Interiors of 2019. The ethereal space included a bathroom that is notably devoid of boxes or clutter of any kind. The cedar ceiling abuts Towada stone walls. Drawing from his heritage, Sugimoto even incorporated salved stones from a now-defunct Kyoto tram station to lay under the cypress tub.

Our client Hiroshi Sugimoto’s collaboration with luxury fragrance house Diptyque, entitled Fragrance of Infinity. Imaga via Diptyque.

In 2021, Sugimoto joined a host of other prominent artists to participate in French cosmetics brand Diptyqe’s limited edition perfume bottles to celebrate the fragrance house’s 60th anniversary. The finished product was inspired by Sugimoto’s childhood memories of seeing the ocean for the first time. Drawing inspiration from the Japanese province of Kankitsuzan, the completed piece evokes an exploration between man and nature. Read more about the collection here.

Moving into 2022, Sugimoto continued to leap across mediums and grow as one of strongest artistic voices of the modern age. In 2022, Sugimoto broke ground on another major installation – a highly-anticipated sculpture garden gracing the Smithsonian Institution. Prominent artists Jeff Koons and Laurie Anderson were in attendance for the ceremony, as was none other than First Lady Jill Biden. The presence of these esteemed guests should come as no surprise. Sugimoto is a superbly talented artist, photographer, architect, and visionary. It is a true honor and privilege to call him a long-time client and for Amineddoleh & Associates to have represented his legal needs for so many valuable art projects, including the above-referenced works.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 25, 2023 |

Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court released its highly anticipated decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al. Art law and intellectual property law attorneys and scholars had been anxiously awaiting the decision, in hopes it would provide some guidance for the application of the fair use test (a test used to determine whether the use of a copyrighted work may be used without permission). For a background on other recent copyright matters, as well as a look at the lower court decisions in AWF v. Goldsmith, read this earlier journal article or the array of articles written about this long-fought battle.

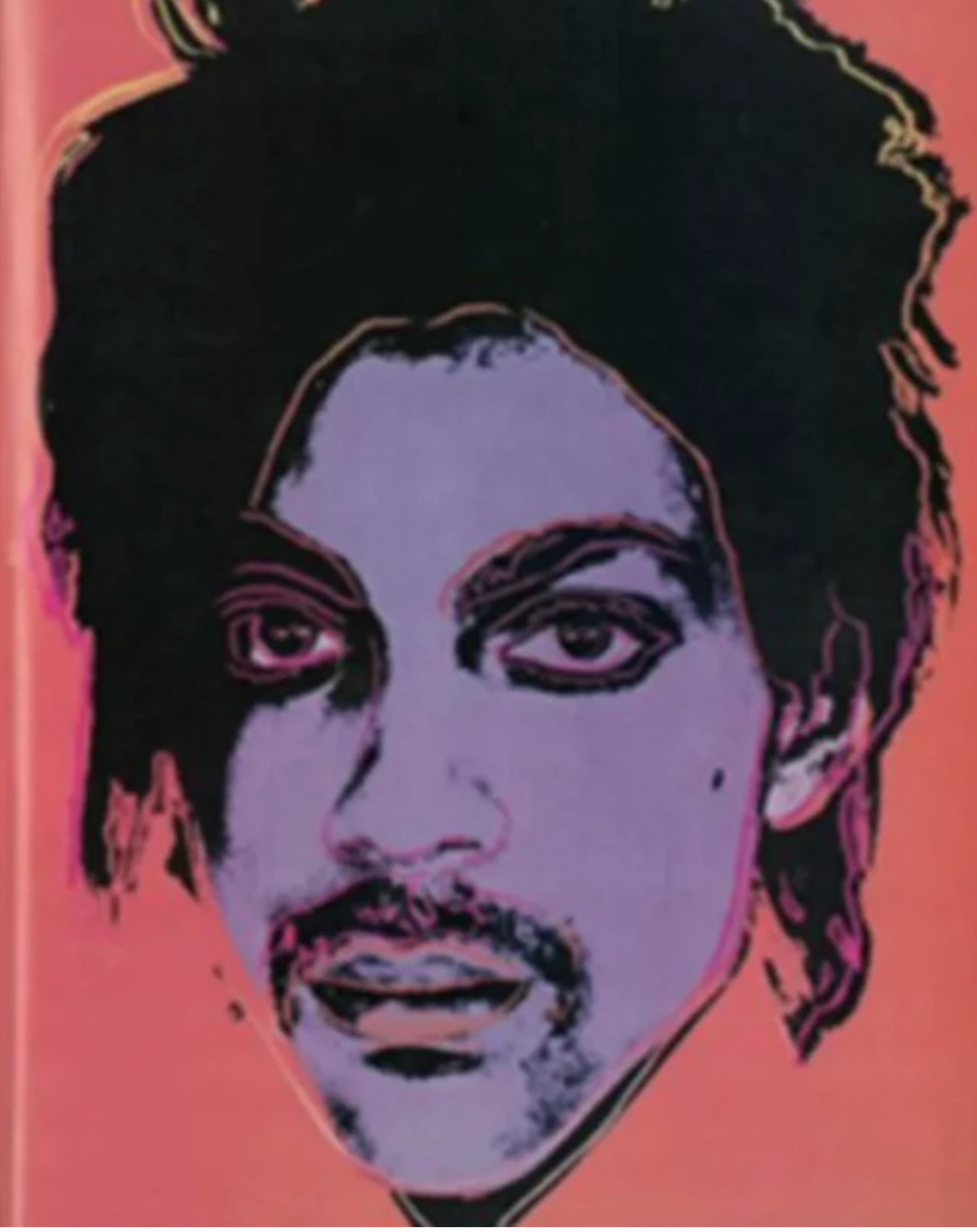

Unfortunately, the high court’s opinion has not provided much clarification. One problem is that the facts here are peculiar, involving a photographer (Goldsmith) who provided a limited license through Vanity Fair that allowed another artist (Warhol) to use her photograph to create a silkscreen work. Unfortunately, Andy Warhol violated the terms of the license, and then decades later his foundation (AWF) sold one of the violating works (“Orange Prince”) to Condé Nast (Vanity Fair’s parent corporation). Condé Nast had licensed the photograph from Goldsmith. In essence, both Goldsmith and AWF were licensing their works to the same publisher (Goldsmith’s license was $400 while AWF charged $10,000). As such, the unusual facts lead to an unusual application of copyright law, not providing helpful guidance (except for the fact that artists should abide by the terms of their licenses).

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

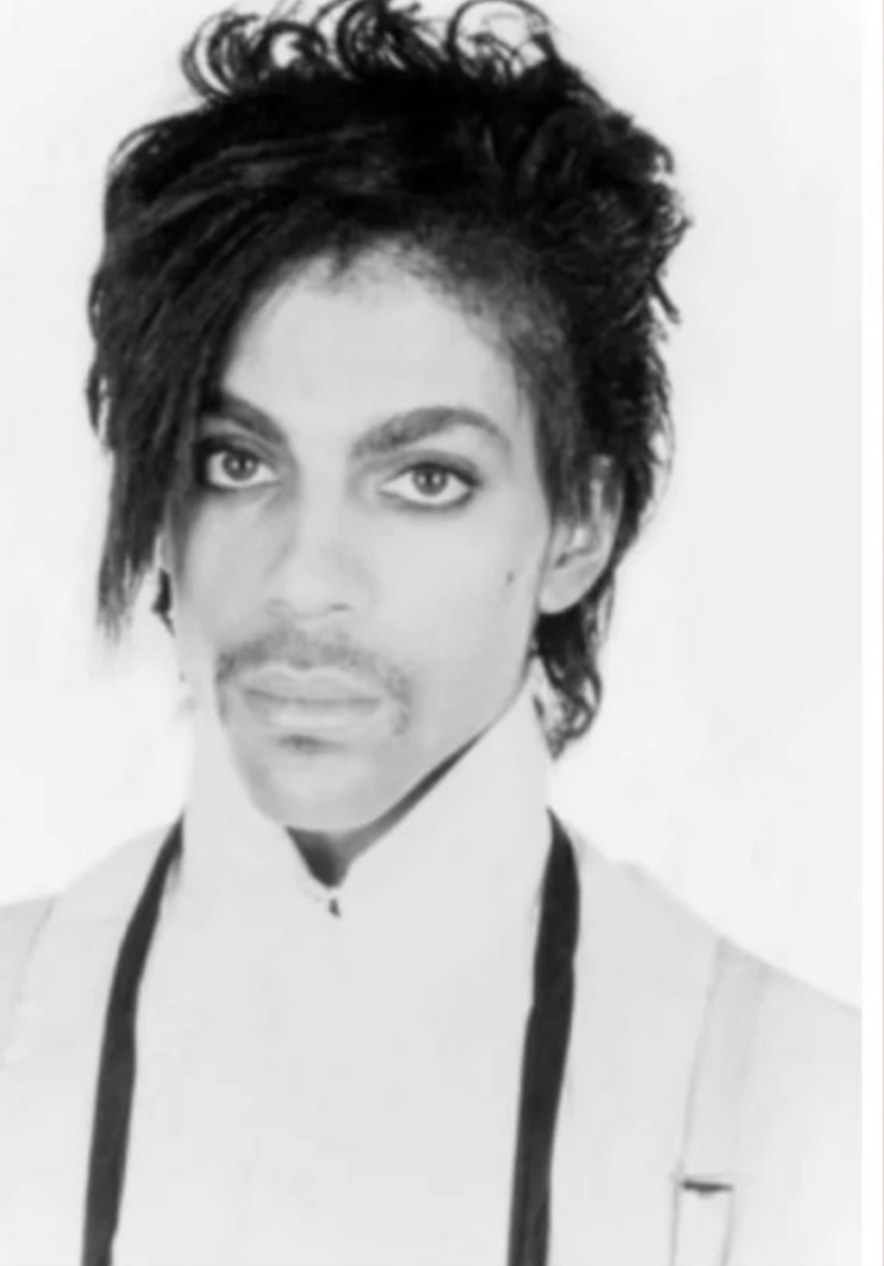

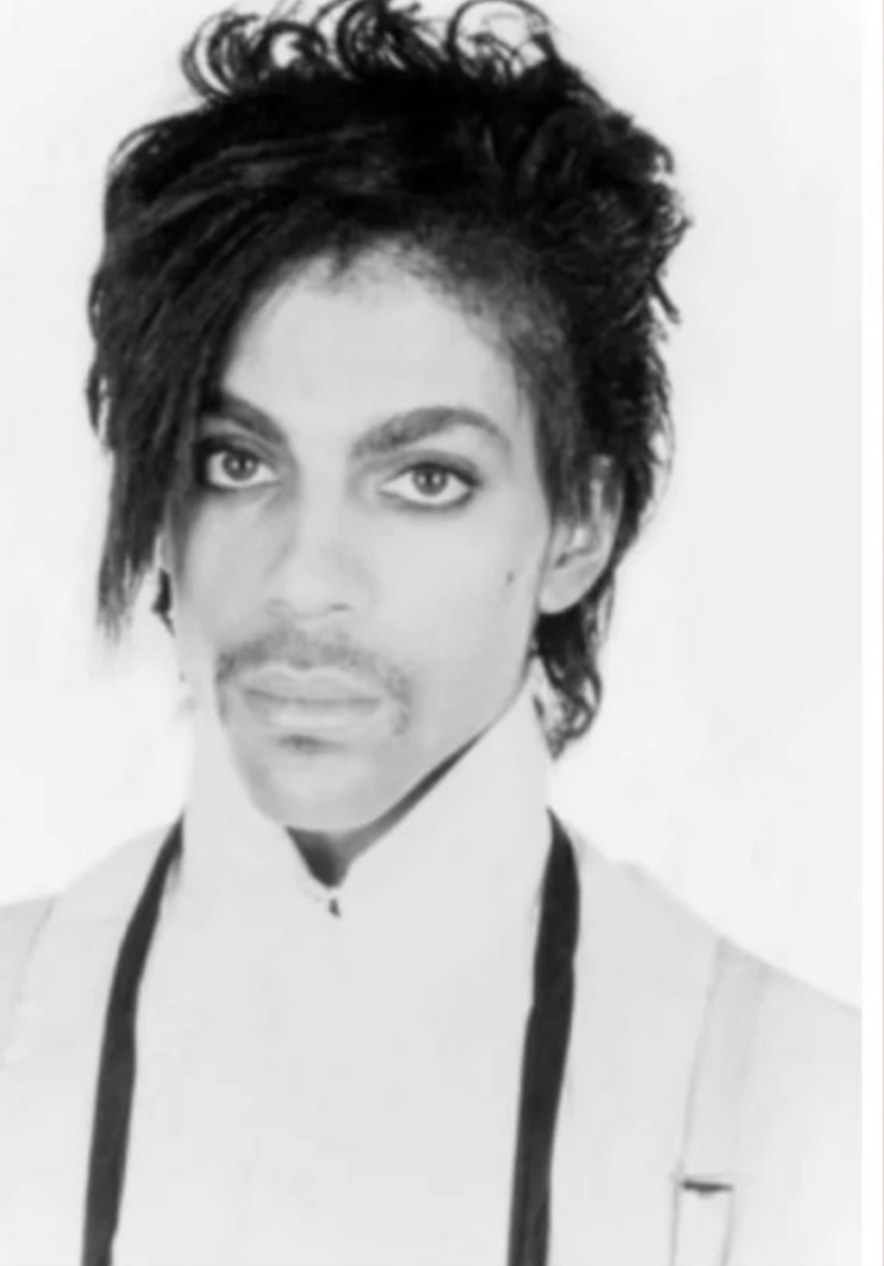

The original Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the artist. Image by Lynn Goldsmith.

As the court aptly noted, the litigation is a dispute between two artists. One of the artists (Warhol) is well known internationally, perhaps one of the best-known artists of the 20th century. The other (Goldsmith) is a trailblazing female photographer, although not a household name. The court’s decision noted that Goldsmith was a rock photographer at a time that the field was dominated by men, and that Goldsmith had “few female peers.” Although not enjoying the same level of fame as Warhol, Goldsmith was an artist in her own right. And while Warhol received a license to use Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince for a single use, he violated the terms and created an additional fifteen works without paying any additional fees. Decades later, the photographer learned of the misuse and informed AWF of the infringement. Rather than seeking a resolution with the spurned artist, AWF sued Goldsmith, filing a declaratory judgment of noninfringement, or alternatively, fair use.

The Southern District of New York granted summary judgment for AWF, finding there was fair use because all four factors of the fair use test (described below) favored AWF. The Second Circuit reversed, finding that all four factors actually weighed in favor of Goldsmith. AWF applied to the US Supreme Court for certiorari, which was granted. The only question before the Supreme Court was whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1), weighs in favor of AWF. On that narrow issue, the Supreme Court agreed with the Second Circuit: the first factor favors Goldsmith.

THE FAIR USE ANALYSIS

Fair use is an exception to copyright protection allowing someone to use a copyrighted work without receiving permission from the copyright holder. Fair use has generally been applied to uses for criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. In determining, courts apply a four-factor analysis outlined in Section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act:

“(1) purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” (17 U.S.C. §107.)

The challenge is that the fair use analysis involves subjective judgments, making some copyright determinations inconsistent.

LEGAL ANALYSIS IN ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION V. GOLDSMITH

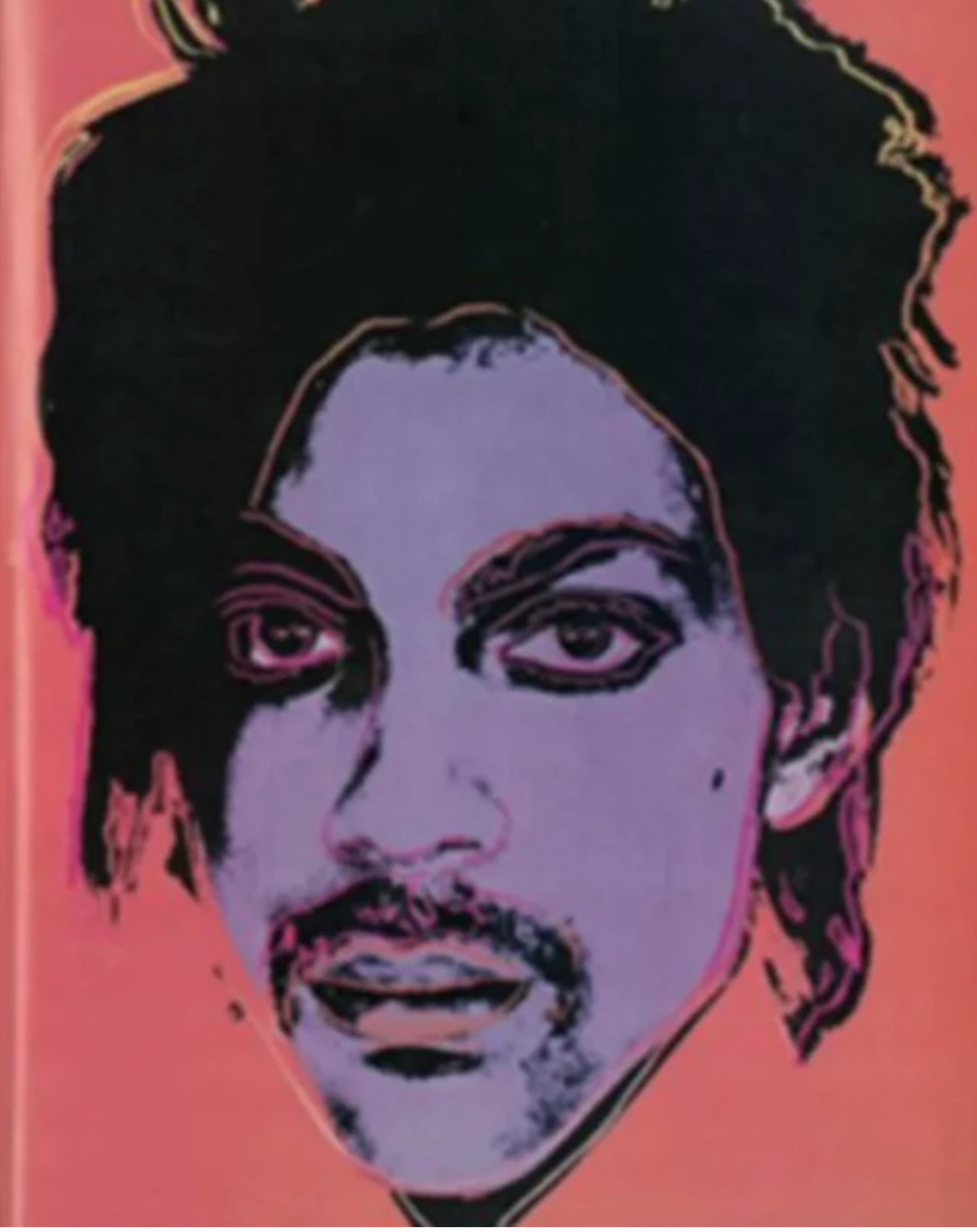

Andy Warhol’s image of the artist. Image via Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

In authoring the majority and dissenting opinions, the justices take off their gloves and grapple with the challenges inherent in the analysis of copyright law, balancing the benefits of incentivizing artists while not overly restricting followers to build off earlier artists. (One of our favorite jabs appears in Footnote 10, when the majority writes, “the dissent begins with a sleight of hand.”) But this goes to demonstrate the difficulty in making a ruling in this dispute. Fair use determinations have always been fraught with uncertainty, especially when relating to artists pushing the envelope, with appropriation artists creating particularly challenging scenarios.

Here, the justices had difficulty reviewing the first prong of the fair uses test. The majority ultimately balanced the degree of difference in character of the works (transformativeness) with other considerations, like commercialism. The Supreme Court dialed back the importance of “transformativeness” in the fair use analysis. A decade earlier, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals indicated that the most important factor in a fair use analysis is transformativeness. Essentially, in Prince v. Cariou, the Second Circuit made transformative use the primary test of fair use, allowing that consideration to outweigh the other factors in the four-part test. The decision was shocking at the time, providing more protection to appropriation artists, but leaving fewer options for those seeking the more traditional protections under copyright law.

Unlike the Second Circuit in Prince v. Cariou, the Supreme Court noted that the fair use test is a 4-factor balancing test, with transformativeness itself not enough to justify fair use. The Court remarked that “‘transformative use’ would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works…” The majority opinion also noted that Warhol’s silkscreen did not comment on Goldsmith’s photograph (commenting on the photo itself would likely be parody and considered a fair use), but rather, Warhol used the photo simply because it was helpful in the creation of the secondary silkscreen work. This was not enough to allow fair use because Goldsmith’s photo and Warhol’s silkscreen had similar commercial uses, illustrating a magazine story on Prince.

The Court instructs that fair use must balance between original and secondary works based in part on the purpose and character of use, including whether it is commercial and why there was copying. The Court warns that Goldsmith’s works are entitled to copyright protection, “even against famous artists.” As such, the Court held that it would be beneficial to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work, in part because these payments are incentives for artists to create original works.

The concurrence (authored by Gorsuch and joined by Jackson) agrees that the undisputed facts demonstrate that AWF used the silkscreen image as a commercial substitute for Goldsmith’s photograph.

THE FIERY DISSENT

The majority’s opinion is somewhat defensive while the dissent is fiery and oozes with art historical references. The majority jabs the dissenters by accurately (and painfully) stating, “The Lives of the Artists undoubtedly makes for livelier reading than the U. S. Code or the U. S. Reports, but as a court, we do not have that luxury.” However, the dissent seemingly enjoys this opportunity to reference art, music, and literature to argue that artists have always copied others.

Kagan’s dissent is artful and insightful with its impassioned pleas and fear for the future of the art world. She argues that the case “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.” It is true that art history is full of creators building upon the work of others, and there is some fear that the holding in this case could stifle creativity, especially with appropriation art. However, the Court’s finding here is not a bar against appropriation art, but rather a decision deeming it unfair when the commercial purpose is so closely aligned between the original and secondary works.

The Copyright Act was passed to provide an author with a bundle of rights that includes the right to reproduce the work and create derivative works. This is balanced by the fair use test (17 U. S. C. §107), a 4-factor balancing test, that allows artists access to the use of an underlying work, under certain circumstances. But the fair use analysis does not allow other creators a free-for-all. (It’s also important to note once again that Goldsmith did not only rely on the Copyright Act to protect her rights, but she also negotiated and contracted to provide Warhol with a limited license to create one image. It is reasonable to assume that Andy Warhol could have complied with the terms of his license or paid an additional fee for the use of Goldsmith’s photographic works.)

It should also be acknowledged that Goldsmith did not initiate this lengthy legal battle. When she confronted AWF, the Foundation could have addressed the issue with the photographer, rather than filing for declaratory judgment.

At the end of the day, the Supreme Court itself struggled in the battle between transformativeness versus commercialism, something that has long faced judges in applying the fair use analysis.