Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court released its highly anticipated decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al. Art law and intellectual property law attorneys and scholars had been anxiously awaiting the decision, in hopes it would provide some guidance for the application of the fair use test (a test used to determine whether the use of a copyrighted work may be used without permission). For a background on other recent copyright matters, as well as a look at the lower court decisions in AWF v. Goldsmith, read this earlier journal article or the array of articles written about this long-fought battle.

Unfortunately, the high court’s opinion has not provided much clarification. One problem is that the facts here are peculiar, involving a photographer (Goldsmith) who provided a limited license through Vanity Fair that allowed another artist (Warhol) to use her photograph to create a silkscreen work. Unfortunately, Andy Warhol violated the terms of the license, and then decades later his foundation (AWF) sold one of the violating works (“Orange Prince”) to Condé Nast (Vanity Fair’s parent corporation). Condé Nast had licensed the photograph from Goldsmith. In essence, both Goldsmith and AWF were licensing their works to the same publisher (Goldsmith’s license was $400 while AWF charged $10,000). As such, the unusual facts lead to an unusual application of copyright law, not providing helpful guidance (except for the fact that artists should abide by the terms of their licenses).

FACTUAL BACKGROUND

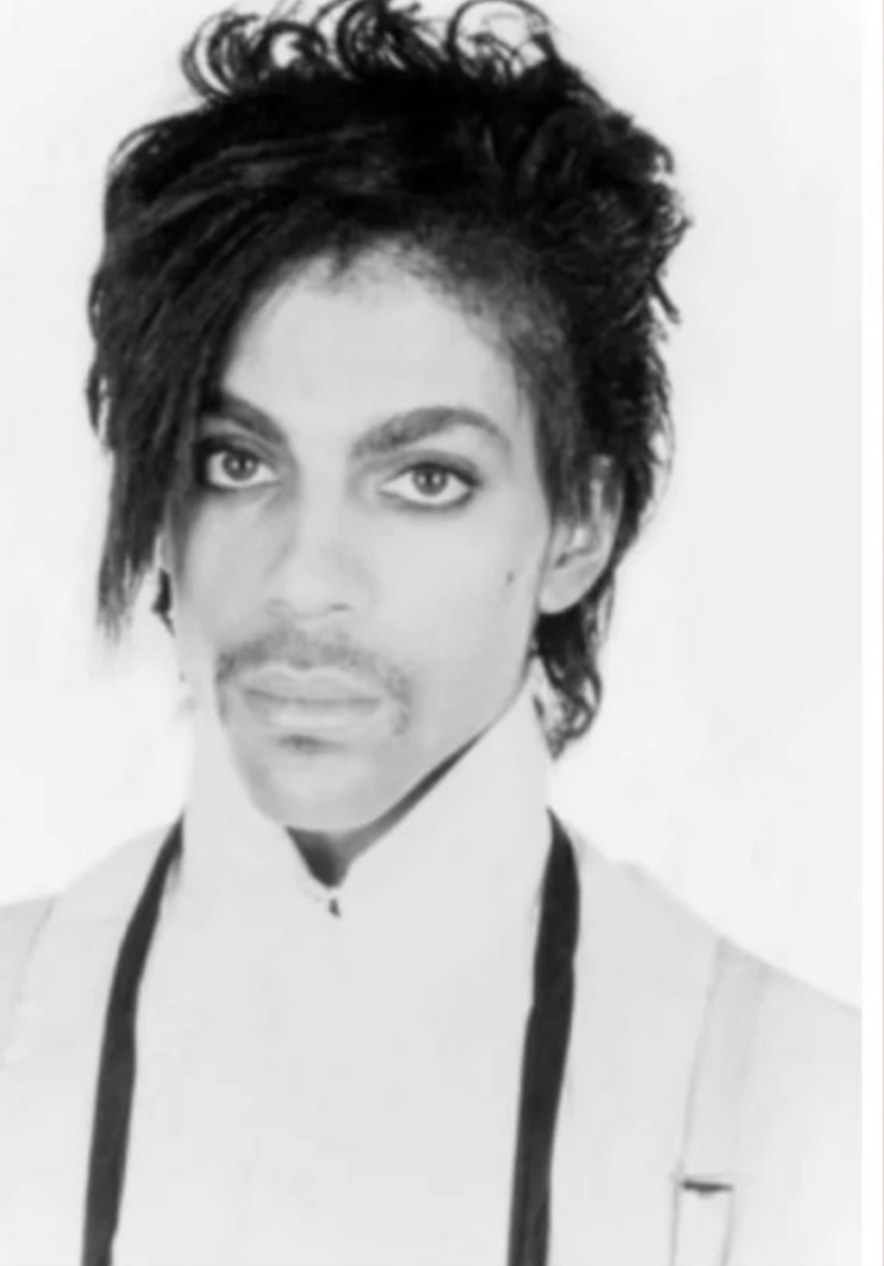

The original Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the artist. Image by Lynn Goldsmith.

As the court aptly noted, the litigation is a dispute between two artists. One of the artists (Warhol) is well known internationally, perhaps one of the best-known artists of the 20th century. The other (Goldsmith) is a trailblazing female photographer, although not a household name. The court’s decision noted that Goldsmith was a rock photographer at a time that the field was dominated by men, and that Goldsmith had “few female peers.” Although not enjoying the same level of fame as Warhol, Goldsmith was an artist in her own right. And while Warhol received a license to use Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince for a single use, he violated the terms and created an additional fifteen works without paying any additional fees. Decades later, the photographer learned of the misuse and informed AWF of the infringement. Rather than seeking a resolution with the spurned artist, AWF sued Goldsmith, filing a declaratory judgment of noninfringement, or alternatively, fair use.

The Southern District of New York granted summary judgment for AWF, finding there was fair use because all four factors of the fair use test (described below) favored AWF. The Second Circuit reversed, finding that all four factors actually weighed in favor of Goldsmith. AWF applied to the US Supreme Court for certiorari, which was granted. The only question before the Supreme Court was whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1), weighs in favor of AWF. On that narrow issue, the Supreme Court agreed with the Second Circuit: the first factor favors Goldsmith.

THE FAIR USE ANALYSIS

Fair use is an exception to copyright protection allowing someone to use a copyrighted work without receiving permission from the copyright holder. Fair use has generally been applied to uses for criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. In determining, courts apply a four-factor analysis outlined in Section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act:

“(1) purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” (17 U.S.C. §107.)

The challenge is that the fair use analysis involves subjective judgments, making some copyright determinations inconsistent.

LEGAL ANALYSIS IN ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION V. GOLDSMITH

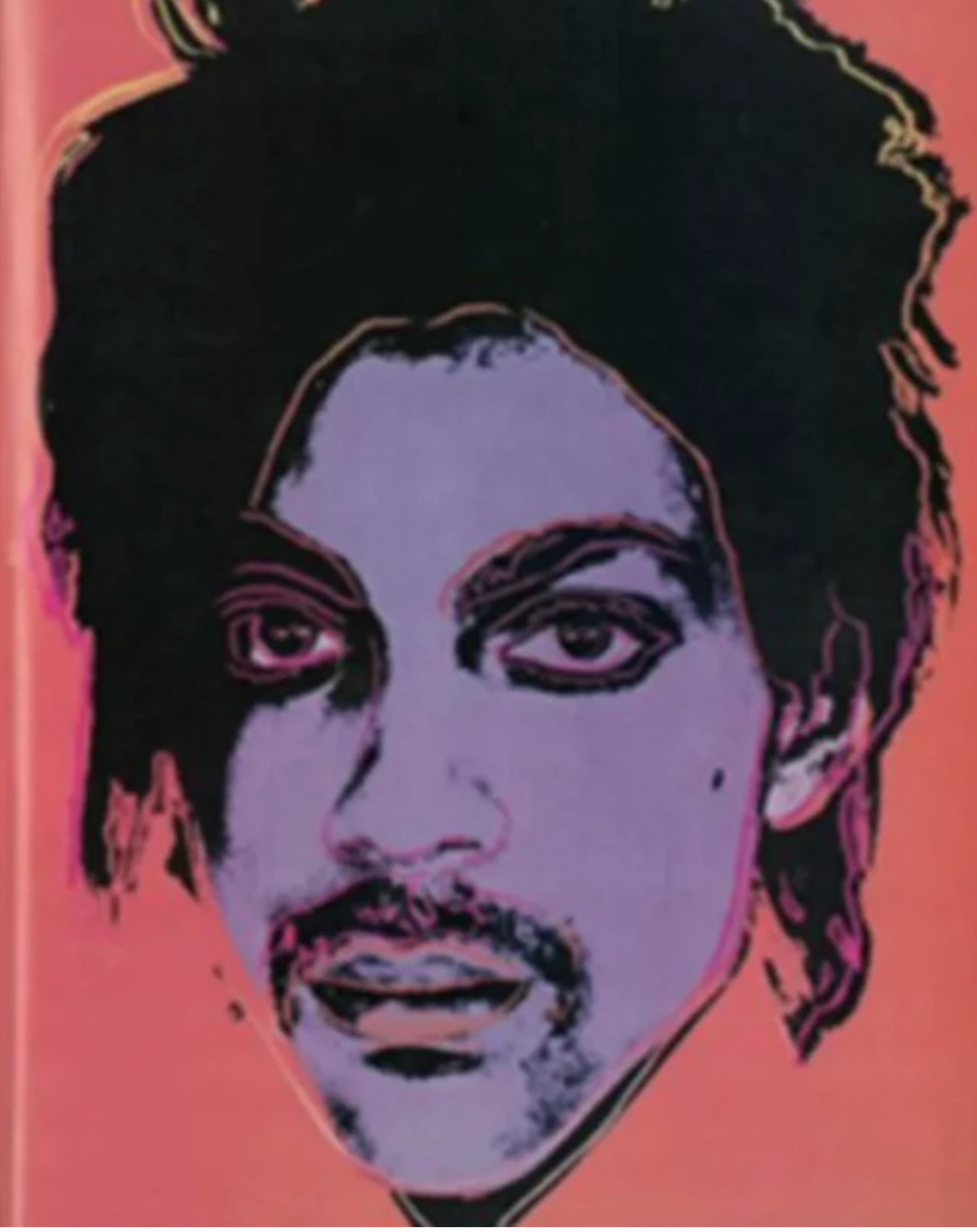

Andy Warhol’s image of the artist. Image via Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

In authoring the majority and dissenting opinions, the justices take off their gloves and grapple with the challenges inherent in the analysis of copyright law, balancing the benefits of incentivizing artists while not overly restricting followers to build off earlier artists. (One of our favorite jabs appears in Footnote 10, when the majority writes, “the dissent begins with a sleight of hand.”) But this goes to demonstrate the difficulty in making a ruling in this dispute. Fair use determinations have always been fraught with uncertainty, especially when relating to artists pushing the envelope, with appropriation artists creating particularly challenging scenarios.

Here, the justices had difficulty reviewing the first prong of the fair uses test. The majority ultimately balanced the degree of difference in character of the works (transformativeness) with other considerations, like commercialism. The Supreme Court dialed back the importance of “transformativeness” in the fair use analysis. A decade earlier, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals indicated that the most important factor in a fair use analysis is transformativeness. Essentially, in Prince v. Cariou, the Second Circuit made transformative use the primary test of fair use, allowing that consideration to outweigh the other factors in the four-part test. The decision was shocking at the time, providing more protection to appropriation artists, but leaving fewer options for those seeking the more traditional protections under copyright law.

Unlike the Second Circuit in Prince v. Cariou, the Supreme Court noted that the fair use test is a 4-factor balancing test, with transformativeness itself not enough to justify fair use. The Court remarked that “‘transformative use’ would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works…” The majority opinion also noted that Warhol’s silkscreen did not comment on Goldsmith’s photograph (commenting on the photo itself would likely be parody and considered a fair use), but rather, Warhol used the photo simply because it was helpful in the creation of the secondary silkscreen work. This was not enough to allow fair use because Goldsmith’s photo and Warhol’s silkscreen had similar commercial uses, illustrating a magazine story on Prince.

The Court instructs that fair use must balance between original and secondary works based in part on the purpose and character of use, including whether it is commercial and why there was copying. The Court warns that Goldsmith’s works are entitled to copyright protection, “even against famous artists.” As such, the Court held that it would be beneficial to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work, in part because these payments are incentives for artists to create original works.

The concurrence (authored by Gorsuch and joined by Jackson) agrees that the undisputed facts demonstrate that AWF used the silkscreen image as a commercial substitute for Goldsmith’s photograph.

THE FIERY DISSENT

The majority’s opinion is somewhat defensive while the dissent is fiery and oozes with art historical references. The majority jabs the dissenters by accurately (and painfully) stating, “The Lives of the Artists undoubtedly makes for livelier reading than the U. S. Code or the U. S. Reports, but as a court, we do not have that luxury.” However, the dissent seemingly enjoys this opportunity to reference art, music, and literature to argue that artists have always copied others.

Kagan’s dissent is artful and insightful with its impassioned pleas and fear for the future of the art world. She argues that the case “will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.” It is true that art history is full of creators building upon the work of others, and there is some fear that the holding in this case could stifle creativity, especially with appropriation art. However, the Court’s finding here is not a bar against appropriation art, but rather a decision deeming it unfair when the commercial purpose is so closely aligned between the original and secondary works.

The Copyright Act was passed to provide an author with a bundle of rights that includes the right to reproduce the work and create derivative works. This is balanced by the fair use test (17 U. S. C. §107), a 4-factor balancing test, that allows artists access to the use of an underlying work, under certain circumstances. But the fair use analysis does not allow other creators a free-for-all. (It’s also important to note once again that Goldsmith did not only rely on the Copyright Act to protect her rights, but she also negotiated and contracted to provide Warhol with a limited license to create one image. It is reasonable to assume that Andy Warhol could have complied with the terms of his license or paid an additional fee for the use of Goldsmith’s photographic works.)

It should also be acknowledged that Goldsmith did not initiate this lengthy legal battle. When she confronted AWF, the Foundation could have addressed the issue with the photographer, rather than filing for declaratory judgment.

At the end of the day, the Supreme Court itself struggled in the battle between transformativeness versus commercialism, something that has long faced judges in applying the fair use analysis.