by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 27, 2022 |

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing: fashion week. With New York Fashion Week already behind us, Milan Fashion Week coming to a close, and Paris Fashion Week mere days from kicking off, the intersection of art, high fashion, and daily life has come together in multiple shows celebrating streetwear as haute couture (although this isn’t the first time fashion brands have taken visual inspiration from art on the street).

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing: fashion week. With New York Fashion Week already behind us, Milan Fashion Week coming to a close, and Paris Fashion Week mere days from kicking off, the intersection of art, high fashion, and daily life has come together in multiple shows celebrating streetwear as haute couture (although this isn’t the first time fashion brands have taken visual inspiration from art on the street).

Looking rumpled, it turns out, is an art form. Custom, high-end designer streetwear is no new phenomenon. Take fashion designer Dapper Dan’s (Daniel Day’s) styling of hip-hop moguls in the 1980s. Through innovative silk-screening and layering techniques (and at a hefty price-point), Dapper Dan fused high fashion with an everyday wearability, heightening the drama of the growing hip-hop music scene. For Dapper Dan (who goes by “Dap”) and others who take guidance from his work, including Savile Row’s Rav Matharu of Clothsurgeon’s bespoke streetwear, the challenge of creating these garments lies in blending high-end luxury with the lifestyle the current wearer is already living. This sometimes involves the use of someone else’s corporate branding in the streetwear’s design. As a result, promoting and selling the final product can become nearly as tricky as the production of the garment itself.

Dapper Dan, for example, famously faced legal challenges from Italian fashion giants Gucci and Fendi, for screen-printing their logos on his leather pieces and outwear designs. In fact, Dapper Dan faced so many lawsuits from Fendi, Gucci, and other luxury brands after incorporating their logos into his designs that he was sued out of business in 1992 and forced to close his Harlem boutique.

The reason fashion houses are often quick to initiate lawsuits when they see their work being used elsewhere is because fashion is a billion-dollar global industry. Yes, artistic ingenuity, originality, and fame are at stake when a designer’s work or logo is being copied without authorization – but so is the potential for a large settlement.

Often, the exact amount that is paid in a settlement is kept private between the parties to the lawsuit, such as the case between Hell’s Angels and luxury designer Alexander McQueen. In 2010, Hell’s Angels sued McQueen for using its “winged skull” motif on bags and jewelry. Not only did McQueen settle with Hell’s Angels for an undisclosed amount, but the suit became so intense that the fashion house actually promised to destroy the merchandise that contained the Hell’s Angels winged skull design.

The secrecy element begs the question: how much is an undisclosed settlement worth in a fashion trademark lawsuit? Gucci’s lawsuit against fast-fashion brand Guess may provide some insights. In 2012, Guess paid Gucci $4.7 million dollars in damages for trademark infringement of Gucci’s interlocking “G” and diamond print logo that Guess used on shoes and other accessories. However, this settlement, astonishing as it was, was considered a blow to Gucci, because it was only a portion of what Gucci had requested in litigation (a staggering $221 million dollars). Gucci’s expectations in this case serve to illustrate both the motivation and the mindset of big fashion houses in their dogged pursuit of trademark claims.

While protecting artistic originality is certainly one of the benefits of fashion trademark lawsuits, along with preventing consumer confusion, there is a strong argument against initiating trademark-based lawsuits involving streetwear brands, specifically. This is because streetwear style can be traced to the intersectionality and collaboration behind the 1970s hip-hop movement. The community-building expression of the diasporic cultural narratives of Black, Latinx, and Caribbean histories continue to provide a foundation for the styles seen on this fall’s runways. The roots of streetwear, both on stage and in the audience, are principled on the sharing, refining, and reworking of culture. Thus, streetwear must reference (and sometimes infringe upon) our worship of consumeristic branding, in order to use those same brands to tell a new story.

Due to this process, Dapper Dan (“Dap”) is a good example of a streetwear designer whose artistic freedom thrives on appropriating other designers as a form of cultural commentary. In the words of rapper Darold Ferguson, Jr (“A$AP Ferg”), [w]hat Dap did was take what those major fashion labels were doing and made them better.” In doing so, “Dap curated hip-hop culture.” Through this lens of Dap as a “cultural curator,” Dap’s forced closure of his boutique in 1992 becomes even more heartbreaking, because it was the result of legal challenges brought against him by large fashion houses with significantly greater financial resources. This worked against his emergence as both an outstanding artistic talent and a cultural icon.

A framework for streetwear designers to cohabitate with luxury brands in the industry in a way that is artistically and economically beneficial to both sides is clearly required. Fortunately, for Dap, this came to fruition in the re-emergence of his Harlem boutique in 2018, reincarnated through his son’s opening of a new Harlem store. The joint venture was backed by none other than Gucci – the same Gucci whose legal challenges once threatened to ruin Dap.

Dap and Gucci’s collaboration provides a basis for streetwear designers to obtain artistic freedom to reinvent styles through commentary on current culture, the results of which construct a stage to effect social change. At the same time, streetwear brands are not forced to appropriate luxury trademarks to spark activism through fashion. Avoiding trademark infringement in streetwear is a tall order, but it can be done. At this year’s fashion week, it was done flawlessly.

Take Disco Inferno & 14N1’s Fall 2022 show entitled More Fashion, Less Gun Violence, to witness a stunning evocation of streetwear fashion’s ability to tell the story of humankind. The show brings hope to an incredibly dark shared history, and does so through an impeccable (if casual) fit.

When checking out the shows this year, keep an eye out for the intersection of streetwear and high-fashion, and how the combination references the roots of the American hip-hop cultural movement. Notice the dominance of luxury logos featured on runway models and front-row attendees, alike. Should brands be prevented from reworking luxury trademarks in their designs in order to criticize contemporary culture? When should the law protect the fashion houses, and their economic stakes, by protecting their marks?

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Mar 14, 2022 |

As practitioners working in the art and intellectual property realm, our team remains apprised of developments in these areas. Of course it is also a pleasure to publish articles on art and IP law topics for practitioners and others interested in these areas. Leila’s recent article for the Institute of Art & Law examines recent developments in copyright law. The landscape of copyright law has recently gone through unexpected developments with a number of cases that have left some artists uneasy about the Fair Use Exception and the use of copyrighted materials in appropriation art. Please contact the Institute of Art & Law for a copy of Leila’s informative article.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Dec 6, 2021 |

Last month our founder was honored to present a 3-hour lecture on the topic of NFTs and collectibles for the EXECUTIVE MASTER IN ART MARKET STUDIES the University of Zurich. During her lecture, she spoke about a high-profile litigation involving NFTs (a discussion of the case follows). Amineddoleh & Associates LLC had been at the forefront of the NFT market, working with platforms (including Nifty Gateway), automated contract providers (Monax), and minters, artists, and collectors.

As the popularity of NFTs continues to grow, legal questions and controversies have arisen in this emerging field. Several of these disputes concern artists’ rights over the minted material that is being sold, sometimes without their knowledge or consent. However, in other cases, copyright holders (who are not the creators of the source material) are alleging infringement and filing suit to prevent the sale and distribution of NFTs.

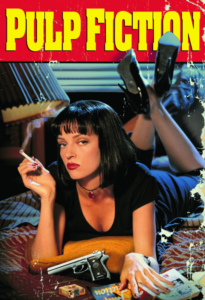

Copyright: Miramax

A recent case involves celebrated director Quentin Tarantino. Early last month, he announced he seven secret NFTs of uncut, exclusive scenes from his cult film, Pulp Fiction. The film, released in 1994, was written and directed by Tarantino, produced by Lawrence Bender and starred Hollywood heavyweights John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson, and Uma Thurman. It was Miramax’s first release after being acquired by Disney and it was completely financed by Miramax. Since its release, Pulp Fiction has earned critical acclaim. It has grossed over $213 million worldwide and Tarantino won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. The highly-anticipated Pulp Fiction NFT collection will consist of seven tokens, each of which will be a single, iconic scene “from the never-before-seen, handwritten screenplay” and will contain “personalized audio commentary” from Tarantino. The NFT announcement prompted Miramax to SUE Tarantino in California for breach of contract, as well as copyright and trademark infringement.

Pulp Fiction Secret NFTs

As part of the sale process for Mr. Tarantino’s NFTs, a WEBSITE HAS BEEN CREATED which provides information about secret NFTs generally and the Pulp Fiction series. The website also offers access to an interest form and waiting list, along with instructions on how to buy the NFTs. It explains that the NFTs are part of a new asset class, called secret NFTs. Secret NFTs have enhanced privacy and access controls and live on the Secret Network. This means that the “owner will enjoy the freedom of choosing between: 1. Keeping the secrets to themselves for all eternity. 2. Sharing the secrets with a few trusted loved ones. 3. Sharing the secrets publicly with the world.”

Miramax’s Legal Arguments

Miramax bringing out the “big guns”

Copyright: Miramax

Shortly after Tarantino’s announcement, Miramax served him with a CEASE-AND-DESIST LETTER on November 4. According to Miramax, Mr. Tarantino’s plan to sell “intensified and expanded” when @TarantinoNFTs tweeted that the Pulp Fiction NFTs will include scans of pages from Pulp Fiction script and the Artifacts Collection of iconic props from Mr. Tarantino’s major films including “one from Pulp Fiction.”

On November 16, Miramax filed a lawsuit against Tarantino in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. The complaint alleges breach of contract, copyright infringement, trademark infringement, and unfair competition. Miramax claims that Tarantino’s limited contractual rights over Pulp Fiction, which include interactive games, live performances, and other ancillary media, exclude NFTs linked to the screenplay. Tarantino has the right to publish portions of the screenplay, but the proposed sale of original pages or scenes in NFT format could be considered a one-time transaction rather than a publication. Moreover, the company argues that Tarantino’s use of Pulp Fiction branding and imagery will confuse buyers into thinking that the NFTs are official Miramax products. However, this has not deterred Tarantino from proceeding with the upcoming sale.

Miramax is seeking a jury trial, unspecified monetary damages, and injunctive relief, aiming to stop planned December sale, as well as frustrate any of Tarantino’s future efforts infringing on what Miramax believes to be its rights to Pulp Fiction. The company is concerned that if Tarantino prevails, this will set a PRECEDENT for other creators to “exploit Miramax films through NFTs and other emerging technologies, when in fact Miramax holds the rights for these films.” The effects of a ruling in favor of Tarantino could spill over to other film companies, placing them in direct competition with creators. For example, when a company releases and sells NFTs related to a film (as in the case of Space Jam: A New Legacy during July 2021), those profits may need to be shared.

The complaint outlined that Tarantino was subject to several agreements limiting his rights to reproduce certain content related to Pulp Fiction. This included a Rights Agreement between Tarantino, Bender, and Miramax, a transfer of rights agreement between Tarantino and B25 Productions with Miramax’s consent, an assignment agreement for the benefit of Miramax, as well as several other agreements.

Under these agreements, Miramax states that they were granted:

“all rights (including all copyrights and trademarks) in and to the Film (and all elements thereof in all stages of development and production) now or hereafter known including without limitation the right to distribute the Film in all media now or hereafter known (theatrical, non-theatrical, all forms of television, home video, etc.).”

However, the contracts also reserve rights to Tarantino, including: “soundtrack album, music publishing, live performance, print publication (including without limitation screenplay publication, ‘making of’ books, comic books and novelization, in audio and electronic formats as well, as applicable), interactive media, theatrical and television sequel and remake rights, and television series and spinoff rights.”

Given the rights granted to each party, Miramax believes that Tarantino is in breach of contract, as well as infringing on Miramax’s copyrights. The question turns on whether these NFTs are covered by the rights reserved by Tarantino.

In the complaint, Miramax distinguishes the language used to grant each party their rights. It characterizes Tarantino’s reserved right as a “narrowly-drafted, static exception to Miramax’s broad, catch-all rights” and “do[es] not contain any forward-looking language.” By contrast, the language used to describe Miramax’s rights is labeled as broad and forward looking. It grants Miramax “all rights . . . now or hereafter known . . . in all media now or hereafter known”.

Regardless of the specific forward-looking language in the contracts, the rights do not specifically address NFTs. Over three decades ago, the parties to the agreements did not contemplate the existence of NFTs. Thus, this gives either party arguments as to why the rights in the contracts may or may not allow the sale of these NFTs.

Tarantino’s Legal Argument

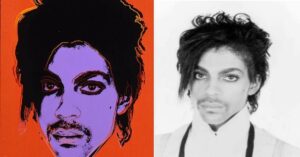

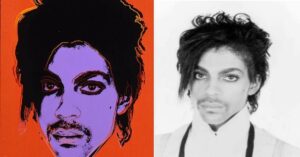

Image from Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith litigation

Tarantino’s counsel stated in an email to Miramax that he and his client believe that the NFTs are covered under Tarantino’s reserved “print publication” or “screenplay publication” right. Under copyright law, a small distribution of a protected good, to a limited pool is not considered a “publication” and the complaint argues Tarantino’s proposed sale is of a “few original script pages or scenes” and an NFT is only a “one-time transaction.” However, given the novelty of NFTs, it is unclear whether a court would consider them a “publication.” But, since NFTs can be openly shared and produced, this may undermine Miramax’s argument.

Another legal defense that may be available to Tarantino is the Fair Use Doctrine. This allows courts to “avoid the rigid application of the Copyright Act when such application would stifle the very creativity the law was designed to foster” and can be used as an affirmative defense in copyright and trademark infringement cases. Under this doctrine, criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research are listed as purposes for which the use of copyrighted work may be considered fair.A court may also find that the use is fair if the work is deemed transformative.

To determine fair use, courts balance four considerations: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for the copyrighted work. Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694, 705 (2d Cir. 2013). Transformative use must “communicat[e] something new and different from the original or expan[d] its utility.” Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., 804 F.3d 202, 214 (2d Cir. 2015). Simply transposing a work from one medium to another does not necessarily qualify as transformative fair use. See Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 992 F.3d 99 (2021).

It is clear that NFTs are creating a new art market and reconfiguring conceptions of copyright for intangible assets. In the sale of NFTs, the Fair Use Doctrine may protect against constant copyright lawsuits. While some NFTs are parodies or commentaries on popular culture or other well-known images or videos, the Pulp Fiction NFTs are directly related to the product for which Miramax holds the copyrights. However, unlike other NFTs, Tarantino is building on and adding to the copyrighted work. By adding commentary and exclusive material, he is arguably “transforming” the stills encapsulated in the NFT series.

A work used for commercial activity, as compared to non-commercial activity, generally weighs against a finding of fair use. Tarantino’s NFT website states that he is selling the Pulp Fiction NFTs because he “is enamored with Pulp Fiction, a timeless creation, and as such wanted to give the public a new glimpse into the iconic scenes from the screenplay of the film.” Further, the website notes that Tarantino sees himself “as an artist” and these NFTs explore “new, exciting mediums to express his artistic style and ideas.” This suggests that he believes that these NFTs are his artistic expression that builds on this cult classic.

However, it could also be argued that Tarantino’s use of the copyrighted material falls within the scope of commercial use, if one considers the broader NFT market. There is a very large value that could be derived from the sale of these NFTs. The fact that people have been selling NFTs for a monetary benefit may suggest that Tarantino’s sale is commercial and it will weigh against his fair use defense. In terms of financial gain, one of Miramax’s attorneys stated that: “This one-off effort devalues the NFT rights to Pulp Fiction, which Miramax intends to maximize through a strategic, comprehensive approach.” In the company’s opinion, the NFTs are considered economic, rather than artistic, assets and Tarantino has deprived Miramax of this revenue stream.

Nonetheless, it could also be argued that the NFTs are not “simply transposing a work from one medium to another,” which supports Tarantino’s fair use defense. The NFTs will include scenes from the Miramax’s copyrighted material, but they will also include “personalized audio commentary from Quentin Tarantino”. Commentary on major scenes in a critically acclaimed movie from the man that wrote and directed the film is certainly a way of adding to the existing material in a way that could be considered transformative when compared to the original.

As the purpose of the Fair Use Doctrine states, intellectual property laws exist to allow freedom of expression. While Tarantino may have entered into a contractual agreement with Miramax, and Miramax may hold copyrights “to the Film (and all elements thereof in all stages of development and production)” as well as to the “right to distribute the Film in all media now or hereafter known (theatrical, non-theatrical, all forms of television, home video, etc.),” Tarantino is arguably creating new content and is entitled to benefit from his artistic output.

Conclusion

As the NFT market continues to boom, many lawyers are considering novel legal arguments related to digital assets, especially in connection with copyright laws. Miramax v. Pulp Fiction is a lawsuit that is receiving and will continue to attract attention. Both sides have arguments and legal theories in their respective favor. It will certainly be interesting to follow the court’s analysis as it considers this landmark controversy, which will likely serve as a model for future claims, both in and beyond the entertainment industry. It is also possible that new regulations or guidelines will be created to address the specific legal issued posed by NFTs, given the volatility of the crypto market and increased scrutiny by legislators.

It is important for both creators and copyright holders interested in making, buying, and selling NFTs to be aware of their remedies and consult legal professionals where appropriate. Read more on NFTs and the work carried out by Amineddoleh & Associates in this field, INCLUDING a cutting-edge template agreement for Monax, on our BLOG.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 9, 2021 |

Nyan Cat

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, have taken the art world by storm during the last month. With these works raking in millions of dollars in sales, collectors are eyeing digital art and collectibles as viable investments. So what exactly are NFTs? They are crypto assets created by minting a digital file on a blockchain, which serves as an indelible record of ownership, authorship, and other attributes of an associated artwork. Once minted, NFTs can be bought and sold across a variety of platforms, with each subsequent transaction recorded on the blockchain, creating a provenance in real-time with each transaction. These digital files, or tokens, can be associated with both physical and digital art and offer many exciting benefits. For example, the near limitless flexibility in coding these tokens has allowed artists to ensure they receive a fraction of all future sales of an artwork, a remedy artists have been seeking for years and which is known as the Artist’s Resale Right (ARR). For these reasons, NFTs may be found for sale at more than just tech start-ups, and they are making their way into preeminent art institutions. Christie’s recently auctioned its first purely digital work (Beeple’s EVERYDAY-THE FIRST 5000 DAYS) with an accompanying NFT, shattering the record for a price paid for a digital work, with a stunning final hammer price of over $69 million.

Purchasers around the world are now competing to buy an unprecedented amount of digital artwork, memes, and GIFs minted as NFTs. This includes the famous Nyan Cat meme, which sold for nearly $600,000 in February 2021. In total, these sales have amounted to approximately $200,000,000 in the month of March 2021 alone, compared to $250,000 during the entire year of 2020. There is no limit to what can become an NFT; for example, a digital artwork based on Salvator Mundi (the painting controversially attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that shattered auction records when it sold for $450 million in 2017), called Salvator Metaversi, was recently turned into an NFT and placed on the market. It looks as though NFTs are here to stay, and some art market participants are hopeful that they will usher in a brave new era of digital and crypto-based art, helping the market recover from the pandemic-related recession.

Amineddoleh & Associates has been at the forefront of this burgeoning market, working on several cutting-edge matters involving NFTs. We have provided legal counsel to market leader NIFTY Gateway and MONAX, a digital contract management solution, which is launching a feature to wrap legal agreements around NFTs. Although NFTs present exciting new possibilities for artists and collectors, it is unclear how they will interact with existing legal regulations drafted with more traditional objects in mind. This is especially true of intellectual property (IP) law, including copyright and moral rights.

VARA Rights

Intellectual property rights are divided into economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights seek to protect a content creator’s ability to generate revenue based on their creations. For example, a publisher may be prohibited from selling copies of an author’s book without a license, thus depriving the author of revenue he or she is entitled to under copyright law. Moral rights seek to protect the intrinsic aspects of an artist’s creation and are more closely associated with honor and integrity rather than profit. For example, the French Supreme Court ruled in favor of director John Huston’s heirs, who argued that airing a colorized version of the classic silver screen film “The Asphalt Jungle” violated Huston’s moral rights. See Consorts John Huston vs Turner Entertainment Co., Cass., Ch. Civ. 1, May 28, 1991, n°89-19.522, n°89-19.725. In the United States, economic rights are protected by the Constitution and the Copyright Act, while moral rights are protected by the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), an act that was only passed in 1990. VARA solely applies to works of visual art and includes the following moral rights for artists: (1) the right to claim authorship of a work they created; (2) the right to disclaim authorship for a work they did not create; (3) the right to prevent the use of their name on any work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that is prejudicial to the artist’s honor or reputation; and (4) the right to prevent the distortion, mutilation, or modification of a work that would prejudice the artist’s honor or reputation.

Intellectual property rights are divided into economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights seek to protect a content creator’s ability to generate revenue based on their creations. For example, a publisher may be prohibited from selling copies of an author’s book without a license, thus depriving the author of revenue he or she is entitled to under copyright law. Moral rights seek to protect the intrinsic aspects of an artist’s creation and are more closely associated with honor and integrity rather than profit. For example, the French Supreme Court ruled in favor of director John Huston’s heirs, who argued that airing a colorized version of the classic silver screen film “The Asphalt Jungle” violated Huston’s moral rights. See Consorts John Huston vs Turner Entertainment Co., Cass., Ch. Civ. 1, May 28, 1991, n°89-19.522, n°89-19.725. In the United States, economic rights are protected by the Constitution and the Copyright Act, while moral rights are protected by the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), an act that was only passed in 1990. VARA solely applies to works of visual art and includes the following moral rights for artists: (1) the right to claim authorship of a work they created; (2) the right to disclaim authorship for a work they did not create; (3) the right to prevent the use of their name on any work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that is prejudicial to the artist’s honor or reputation; and (4) the right to prevent the distortion, mutilation, or modification of a work that would prejudice the artist’s honor or reputation.

One can imagine how NFTs may help enforce an artist’s economic rights: providing a record of ownership and the opportunity to attach specially contracted rights and obligations into the token (such as royalty rates) could make enforcement more efficient. However, it is less clear how NFTs will facilitate the enforcement of moral rights. In particular, the ability for NFTs to serve as incontrovertible proof of authorship, a chief benefit of NFTs, appears to be incompatible with rights allowing for conditional disavowal of an artist’s work.

Conventional VARA Rights Application

The third and fourth VARA rights, providing for the disavowal of a work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that is prejudicial to the artist’s honor or reputation and for the prevention of such treatment, are sometimes the source of controversial litigation. In the US, moral rights are often seen as competing with traditional norms in property law, especially a subsequent owner’s ability to control his or her own property. Courts often face difficulty balancing intangible artists’ rights against real-world property rights, which has produced surprising results. Just as importantly, the art market is free to render its own decision concerning authorship and value, regardless of what a court of law might determine. The following examples illustrate how moral rights can be a double-edged sword in litigation.

Cady Noland, Log Cabin

Cady Noland, Log Cabin

Photo courtesy of Artnet

Celebrated American artist Cady Noland initiated a string of lawsuits against a collector and German gallery, most recently alleging that her rights under VARA were violated in a matter evoking a modern ship of Theseus. See Noland v. Janssen, No. 17-CV-5452 (JPO), 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 95454 (S.D.N.Y. June 1, 2020). The work in question, Log Cabin, is a facade of a traditional log cabin created using pre-cut lumber ordered from a manufacturer in Montana. In 1955, the work’s then owner, Wilhelm Schürmann, loaned the work to a German museum, where it was displayed outdoors. Years later, several pieces of lumber began to rot and were replaced by conservators using lumber sourced from the same Montana manufacturer. Schürmann would go on to sell the work to Ohio collector Scott Mueller for $1.4 million, who had the foresight to include a buy-back option in the event the work was disavowed. Noland had already achieved some notoriety for disavowing works, which proved to be well-earned when she disavowed Log Cabin in a hand-written fax after learning of the conservation measures.

As one might expect when tempers run as high as sale prices, litigation ensued. Mueller sued the gallery for failing to return the purchase price, and the case was dismissed. See Mueller v. Michael Janssen Gallery PTE. Ltd., 225 F. Supp. 3d 201 (S.D.N.Y. 2016). But then Noland initiated a lawsuit of her own alleging the work infringed upon her copyright. Noland was granted leave to amend her complaint twice, with VARA violations added to her final amended complaint, but the litigation was ultimately dismissed. The judge concluded that Log Cabin was not entitled to copyright protection, and therefore not entitled to protections under VARA; and that in any case, any alleged violation occurred outside the United States. However, the case is just as notable for what it did not decide; namely, whether the unauthorized conservation of Log Cabin constituted a distortion, mutilation, or modification prejudicial to Noland’s honor as an artist. The absence of an answer has led some to question where the line might be drawn and may inspire future artists to make novel arguments along similar lines. As of 2020, Noland’s attorney was considering an appeal.

Richard Prince & Ivanka Trump

Appropriation artist Richard Prince, who has infamously tested the limits of copyright law on several occasions, ironically chose to exercise his VARA rights when he disavowed a work he sold to Ivanka Trump, apparently for political reasons. In a 2017 tweetreading, “This is not my work. I did not make it. I deny. I denounce. This fake art.” Prince publicly disavowed a work featuring his comment on one of Ivanka’s Instagram posts as part of his series “New Portraits.” The tweet followed a series of public statements criticizing Ivanka’s father, then presidential candidate, Donald Trump. The language of the tweet also appears to mimic Trump’s staccato speaking style and reference to “fake” claims. It is not clear whether the tweet would have become the subject of litigation, as Prince later confirmed in an interview that he voluntarily returned the $36,000 he initially received for the piece. Unfortunately, this leaves questions unanswered about under which conditions an artist may disavow an artwork and a disavowal’s effect on the market. In the absence of litigation, Prince’s actions set a non-legal precedent that an artist may disavow a work for political reasons if he or she has the cash on hand to reimburse the purchase price. In the end, Prince may have only increased the value of the work, still held by Ivanka, and whose creation by the artist is well-documented on Instagram.

5Pointz and Aerosol Art

5Pointz murals. Photo Pelle Sten, via Flickr.

Perhaps the most famous case involving the application of VARA involves graffiti mecca, 5Pointz. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals sent shockwaves through the world of copyright when it upheld a staggering $6.75 million damages award based on VARA violations for temporary works of street art. See Castillo v. G&M Realty L.P., 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020). An abandoned warehouse in Queens was transformed into a graffiti mecca colloquially referred to as 5Pointz, a place where some of the city’s most notable (or notorious) street artists vied to make their own contributions to its decorated halls. The building’s owner, Gerald Wolkoff, initially welcomed their attention, and allowed artists to paint the walls under the direction of Jonathan Cohen, a graffiti artist known as Meres One, serving in a curatorial role. The matter was taken to court when Wolkoff wanted to take advantage of rising real estate prices and demolish the building to make way for condominiums. The artists, led by Cohen, protested the destruction, arguing that their works had achieved “recognized stature,” warranting protection under VARA. Then in 2013, while litigation was still pending, Wolkoff whitewashed the entire warehouse under the cover of night.

In 2018, Brooklyn Supreme Court Judge Frederick Block awarded the maximum statutory penalty under VARA, $150,000 per artwork, totaling nearly $7 million in damages. See Cohen v. G&M Realty L.P., 320 F. Supp. 3d 421 (E.D.N.Y. 2018).The 32-page decision was precedential in several ways. First, Judge Block vindicated street artists everywhere when he determined that these artworks had achieved a level of stature meriting copyright protection; in his analysis, he looked beyond the conventional art world for a group that venerated these works, and in doing so, opened the door for a dearth of unconventional art to receive legal protection. Perhaps most notably, the case was under close observation for its potential to establish a precedent for damages under VARA. Clearly influenced by Wolkoff’s surreptitious behavior, Judge Block’s decision to award the maximum penalty was still shocking. The case would work its way up the appellate ladder until finally being rejected for certiorari by the United States Supreme Court in 2020. The case now signals that VARA rights are not to be treated lightly and foretells the dire consequences that can result from a violation.

The above-mentioned disputes illustrate that moral rights cases are complex, and NFTs could further muddy the waters for judges unaccustomed to the peculiarities of the art market and crypto assets. At the moment, there is nothing preventing unscrupulous actors from minting NFTs of works and selling them as their own despite lack of good title, ownership, or IP rights. For instance, a so-called “market disruptor,” GlobalArtMuseum, carried out a “digital art heist” by creating NFTs of famous works held in top-tier museums, such as the Rijksmuseum. GlobalArtMuseum then placed the NFTs for sale on popular marketplace OpenSea. This was a publicity stunt, but nevertheless left the museums rattled. Similar acts could violate copyright law. Tracking down those responsible could prove complicated and the enforcement of legal remedies is not necessarily guaranteed. Online platforms operate across borders, so it may be difficult to determine which law applies, and countless transactions may occur in the meantime. Moreover, some lawyers are not convinced that NFTs qualify for copyright protection because it is an open question as to whether they are original works of authorship. Artists will need to keep this possibility in mind when minting NFTs and exerting moral and economic rights.

Another issue with NFTs pertains to ownership and the integrity of works. A self-proclaimed group of “tech and art enthusiasts” recently purchased a Banksy print, minted it as an NFT – and then burned the original. The group circulated the video of the burning print on YouTube, stating that “by removing the physical piece from existence and only having the NFT, [this]… will ensure that no one can alter the piece and it is the true piece that exists in the world.” This certainly raises the question of authenticity for NFTs when a physical work is also present; which is the original? If the physical work is mutilated or destroyed, but the NFT survives, how will this affect the damages an artist is entitled to receive under VARA? Hypothetically, Banksy could have a viable cause of action under VARA against the group, as his work is certainly of a recognized stature, but no court has ruled on the matter yet.

Conclusion

What does the NFT frenzy tell us? Art is constantly evolving, and the market is quick to adapt once supply and demand for new forms are established. NFTs are operating as a herald of such change, albeit at a much faster pace than anticipated. But this means that current legal and regulatory frameworks are not equipped to deal with some of the issues related to NFTs, including economic and moral rights. Artists entering the world of NFTs should be aware of these issues and consult legal professionals familiar with the pitfalls in this field. Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to represent and advise artists and collectors creating, selling, and purchasing all types of artwork and collectibles – NFTs included.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 8, 2021 |

It’s safe to say that many people are all trying to rebrand themselves after 2020, one of the most challenging years in recent memory. It is no surprise that Burger King is jumping in on the ‘new year, new me’ bandwagon. The company made waves with popular branding strategies in the past– it previously made it possible to “smell like a Whopper,” it released a Whopper air-freshener, it served black burger buns for Halloween, and it even released an absurd yule log sweater for Christmas. Now, the food giant has announced a fresh new logo to kick off the New Year. The fast food chain recently announced it would be rebranding after retiring its current logo of over 20 years. The new logo has a retro style, paying homage to BK’s branding used from 1969-1999, as it aims to “seamlessly meet the brand evolution of the times.” The logo stars a new custom-made font, appropriately titled “Flame.” It is inspired by the rounded and bold shapes of the chain’s signature food. The design has been welcomed as a return to Burger King’s origins while revamping the company’s visual identity.

It’s safe to say that many people are all trying to rebrand themselves after 2020, one of the most challenging years in recent memory. It is no surprise that Burger King is jumping in on the ‘new year, new me’ bandwagon. The company made waves with popular branding strategies in the past– it previously made it possible to “smell like a Whopper,” it released a Whopper air-freshener, it served black burger buns for Halloween, and it even released an absurd yule log sweater for Christmas. Now, the food giant has announced a fresh new logo to kick off the New Year. The fast food chain recently announced it would be rebranding after retiring its current logo of over 20 years. The new logo has a retro style, paying homage to BK’s branding used from 1969-1999, as it aims to “seamlessly meet the brand evolution of the times.” The logo stars a new custom-made font, appropriately titled “Flame.” It is inspired by the rounded and bold shapes of the chain’s signature food. The design has been welcomed as a return to Burger King’s origins while revamping the company’s visual identity.

You too can smell flame-grilled!

Many people wonder what happens behind the scenes of a company’s branding transition, especially business owners looking to do the same. The process may include one of two possible routes: (1) trademark registration or (2) amendment of a currently registered trademark. Either option allows for a quick refresh or rebranding of a logo. However, the requesting party should ensure that it is choosing the best option for its needs. If the current logo is not “materially altered,” an amendment to trademark registration of the company’s logo should suffice to protect the company’s branding for trademark purposes. If, on the other hand, a company is making more than just a simple facelift to the currently registered logo, the best option to ensure protection may be to file a new trademark application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Additionally, companies should be mindful of third parties to whom they may have previously licensed logos. An amendment to, or new registration of, a company’s logo means that current licenses to third parties will be revoked, and a new license may need to be executed. Furthermore, the new logo’s distinctive elements (like BK’s Flame font), may be entitled to additional intellectual property protection, such as copyright.

Although rebranding can be beneficial for a company’s ambitious strategy to create a new visual identity and embrace an appealing philosophy, practical matters are just as important when it comes to trademarks. Failing to comply with USPTO requirements could leave a company vulnerable to costly litigation or the need to amend its logo, if it is unable to register its new logo in time to prevent other parties from using it. The USPTO uses specific criteria when considering trademark applications. To increase your chances of success, you should always consult a legal professional with experience in trademarks. At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, our team has years of practice prosecuting trademark applications and working with clients to actively protect their intellectual property.

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing: fashion week. With New York Fashion Week already behind us, Milan Fashion Week coming to a close, and Paris Fashion Week mere days from kicking off, the intersection of art, high fashion, and daily life has come together in multiple shows celebrating streetwear as haute couture (although this isn’t the first time fashion brands have taken visual inspiration from art on the street).

As everyone in the fashion industry knows, September means one thing: fashion week. With New York Fashion Week already behind us, Milan Fashion Week coming to a close, and Paris Fashion Week mere days from kicking off, the intersection of art, high fashion, and daily life has come together in multiple shows celebrating streetwear as haute couture (although this isn’t the first time fashion brands have taken visual inspiration from art on the street).

Intellectual property rights are divided into economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights seek to protect a content creator’s ability to generate revenue based on their creations. For example, a publisher may be prohibited from selling copies of an author’s book without a license, thus depriving the author of revenue he or she is entitled to under copyright law. Moral rights seek to protect the intrinsic aspects of an artist’s creation and are more closely associated with honor and integrity rather than profit. For example, the French Supreme Court

Intellectual property rights are divided into economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights seek to protect a content creator’s ability to generate revenue based on their creations. For example, a publisher may be prohibited from selling copies of an author’s book without a license, thus depriving the author of revenue he or she is entitled to under copyright law. Moral rights seek to protect the intrinsic aspects of an artist’s creation and are more closely associated with honor and integrity rather than profit. For example, the French Supreme Court

It’s safe to say that many people are all trying to rebrand themselves after 2020, one of the most challenging years in recent memory. It is no surprise that Burger King is jumping in on the ‘new year, new me’ bandwagon. The company made waves with popular branding strategies in the past– it previously made it possible to “

It’s safe to say that many people are all trying to rebrand themselves after 2020, one of the most challenging years in recent memory. It is no surprise that Burger King is jumping in on the ‘new year, new me’ bandwagon. The company made waves with popular branding strategies in the past– it previously made it possible to “