Nyan Cat

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, have taken the art world by storm during the last month. With these works raking in millions of dollars in sales, collectors are eyeing digital art and collectibles as viable investments. So what exactly are NFTs? They are crypto assets created by minting a digital file on a blockchain, which serves as an indelible record of ownership, authorship, and other attributes of an associated artwork. Once minted, NFTs can be bought and sold across a variety of platforms, with each subsequent transaction recorded on the blockchain, creating a provenance in real-time with each transaction. These digital files, or tokens, can be associated with both physical and digital art and offer many exciting benefits. For example, the near limitless flexibility in coding these tokens has allowed artists to ensure they receive a fraction of all future sales of an artwork, a remedy artists have been seeking for years and which is known as the Artist’s Resale Right (ARR). For these reasons, NFTs may be found for sale at more than just tech start-ups, and they are making their way into preeminent art institutions. Christie’s recently auctioned its first purely digital work (Beeple’s EVERYDAY-THE FIRST 5000 DAYS) with an accompanying NFT, shattering the record for a price paid for a digital work, with a stunning final hammer price of over $69 million.

Purchasers around the world are now competing to buy an unprecedented amount of digital artwork, memes, and GIFs minted as NFTs. This includes the famous Nyan Cat meme, which sold for nearly $600,000 in February 2021. In total, these sales have amounted to approximately $200,000,000 in the month of March 2021 alone, compared to $250,000 during the entire year of 2020. There is no limit to what can become an NFT; for example, a digital artwork based on Salvator Mundi (the painting controversially attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that shattered auction records when it sold for $450 million in 2017), called Salvator Metaversi, was recently turned into an NFT and placed on the market. It looks as though NFTs are here to stay, and some art market participants are hopeful that they will usher in a brave new era of digital and crypto-based art, helping the market recover from the pandemic-related recession.

Amineddoleh & Associates has been at the forefront of this burgeoning market, working on several cutting-edge matters involving NFTs. We have provided legal counsel to market leader NIFTY Gateway and MONAX, a digital contract management solution, which is launching a feature to wrap legal agreements around NFTs. Although NFTs present exciting new possibilities for artists and collectors, it is unclear how they will interact with existing legal regulations drafted with more traditional objects in mind. This is especially true of intellectual property (IP) law, including copyright and moral rights.

VARA Rights

Intellectual property rights are divided into economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights seek to protect a content creator’s ability to generate revenue based on their creations. For example, a publisher may be prohibited from selling copies of an author’s book without a license, thus depriving the author of revenue he or she is entitled to under copyright law. Moral rights seek to protect the intrinsic aspects of an artist’s creation and are more closely associated with honor and integrity rather than profit. For example, the French Supreme Court ruled in favor of director John Huston’s heirs, who argued that airing a colorized version of the classic silver screen film “The Asphalt Jungle” violated Huston’s moral rights. See Consorts John Huston vs Turner Entertainment Co., Cass., Ch. Civ. 1, May 28, 1991, n°89-19.522, n°89-19.725. In the United States, economic rights are protected by the Constitution and the Copyright Act, while moral rights are protected by the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), an act that was only passed in 1990. VARA solely applies to works of visual art and includes the following moral rights for artists: (1) the right to claim authorship of a work they created; (2) the right to disclaim authorship for a work they did not create; (3) the right to prevent the use of their name on any work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that is prejudicial to the artist’s honor or reputation; and (4) the right to prevent the distortion, mutilation, or modification of a work that would prejudice the artist’s honor or reputation.

Intellectual property rights are divided into economic rights and moral rights. Economic rights seek to protect a content creator’s ability to generate revenue based on their creations. For example, a publisher may be prohibited from selling copies of an author’s book without a license, thus depriving the author of revenue he or she is entitled to under copyright law. Moral rights seek to protect the intrinsic aspects of an artist’s creation and are more closely associated with honor and integrity rather than profit. For example, the French Supreme Court ruled in favor of director John Huston’s heirs, who argued that airing a colorized version of the classic silver screen film “The Asphalt Jungle” violated Huston’s moral rights. See Consorts John Huston vs Turner Entertainment Co., Cass., Ch. Civ. 1, May 28, 1991, n°89-19.522, n°89-19.725. In the United States, economic rights are protected by the Constitution and the Copyright Act, while moral rights are protected by the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), an act that was only passed in 1990. VARA solely applies to works of visual art and includes the following moral rights for artists: (1) the right to claim authorship of a work they created; (2) the right to disclaim authorship for a work they did not create; (3) the right to prevent the use of their name on any work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that is prejudicial to the artist’s honor or reputation; and (4) the right to prevent the distortion, mutilation, or modification of a work that would prejudice the artist’s honor or reputation.

One can imagine how NFTs may help enforce an artist’s economic rights: providing a record of ownership and the opportunity to attach specially contracted rights and obligations into the token (such as royalty rates) could make enforcement more efficient. However, it is less clear how NFTs will facilitate the enforcement of moral rights. In particular, the ability for NFTs to serve as incontrovertible proof of authorship, a chief benefit of NFTs, appears to be incompatible with rights allowing for conditional disavowal of an artist’s work.

Conventional VARA Rights Application

The third and fourth VARA rights, providing for the disavowal of a work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that is prejudicial to the artist’s honor or reputation and for the prevention of such treatment, are sometimes the source of controversial litigation. In the US, moral rights are often seen as competing with traditional norms in property law, especially a subsequent owner’s ability to control his or her own property. Courts often face difficulty balancing intangible artists’ rights against real-world property rights, which has produced surprising results. Just as importantly, the art market is free to render its own decision concerning authorship and value, regardless of what a court of law might determine. The following examples illustrate how moral rights can be a double-edged sword in litigation.

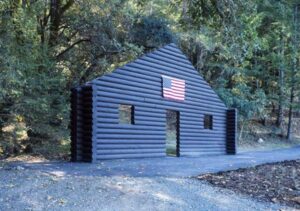

Cady Noland, Log Cabin

Cady Noland, Log Cabin

Photo courtesy of Artnet

Celebrated American artist Cady Noland initiated a string of lawsuits against a collector and German gallery, most recently alleging that her rights under VARA were violated in a matter evoking a modern ship of Theseus. See Noland v. Janssen, No. 17-CV-5452 (JPO), 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 95454 (S.D.N.Y. June 1, 2020). The work in question, Log Cabin, is a facade of a traditional log cabin created using pre-cut lumber ordered from a manufacturer in Montana. In 1955, the work’s then owner, Wilhelm Schürmann, loaned the work to a German museum, where it was displayed outdoors. Years later, several pieces of lumber began to rot and were replaced by conservators using lumber sourced from the same Montana manufacturer. Schürmann would go on to sell the work to Ohio collector Scott Mueller for $1.4 million, who had the foresight to include a buy-back option in the event the work was disavowed. Noland had already achieved some notoriety for disavowing works, which proved to be well-earned when she disavowed Log Cabin in a hand-written fax after learning of the conservation measures.

As one might expect when tempers run as high as sale prices, litigation ensued. Mueller sued the gallery for failing to return the purchase price, and the case was dismissed. See Mueller v. Michael Janssen Gallery PTE. Ltd., 225 F. Supp. 3d 201 (S.D.N.Y. 2016). But then Noland initiated a lawsuit of her own alleging the work infringed upon her copyright. Noland was granted leave to amend her complaint twice, with VARA violations added to her final amended complaint, but the litigation was ultimately dismissed. The judge concluded that Log Cabin was not entitled to copyright protection, and therefore not entitled to protections under VARA; and that in any case, any alleged violation occurred outside the United States. However, the case is just as notable for what it did not decide; namely, whether the unauthorized conservation of Log Cabin constituted a distortion, mutilation, or modification prejudicial to Noland’s honor as an artist. The absence of an answer has led some to question where the line might be drawn and may inspire future artists to make novel arguments along similar lines. As of 2020, Noland’s attorney was considering an appeal.

Richard Prince & Ivanka Trump

Appropriation artist Richard Prince, who has infamously tested the limits of copyright law on several occasions, ironically chose to exercise his VARA rights when he disavowed a work he sold to Ivanka Trump, apparently for political reasons. In a 2017 tweetreading, “This is not my work. I did not make it. I deny. I denounce. This fake art.” Prince publicly disavowed a work featuring his comment on one of Ivanka’s Instagram posts as part of his series “New Portraits.” The tweet followed a series of public statements criticizing Ivanka’s father, then presidential candidate, Donald Trump. The language of the tweet also appears to mimic Trump’s staccato speaking style and reference to “fake” claims. It is not clear whether the tweet would have become the subject of litigation, as Prince later confirmed in an interview that he voluntarily returned the $36,000 he initially received for the piece. Unfortunately, this leaves questions unanswered about under which conditions an artist may disavow an artwork and a disavowal’s effect on the market. In the absence of litigation, Prince’s actions set a non-legal precedent that an artist may disavow a work for political reasons if he or she has the cash on hand to reimburse the purchase price. In the end, Prince may have only increased the value of the work, still held by Ivanka, and whose creation by the artist is well-documented on Instagram.

5Pointz and Aerosol Art

5Pointz murals. Photo Pelle Sten, via Flickr.

Perhaps the most famous case involving the application of VARA involves graffiti mecca, 5Pointz. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals sent shockwaves through the world of copyright when it upheld a staggering $6.75 million damages award based on VARA violations for temporary works of street art. See Castillo v. G&M Realty L.P., 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020). An abandoned warehouse in Queens was transformed into a graffiti mecca colloquially referred to as 5Pointz, a place where some of the city’s most notable (or notorious) street artists vied to make their own contributions to its decorated halls. The building’s owner, Gerald Wolkoff, initially welcomed their attention, and allowed artists to paint the walls under the direction of Jonathan Cohen, a graffiti artist known as Meres One, serving in a curatorial role. The matter was taken to court when Wolkoff wanted to take advantage of rising real estate prices and demolish the building to make way for condominiums. The artists, led by Cohen, protested the destruction, arguing that their works had achieved “recognized stature,” warranting protection under VARA. Then in 2013, while litigation was still pending, Wolkoff whitewashed the entire warehouse under the cover of night.

In 2018, Brooklyn Supreme Court Judge Frederick Block awarded the maximum statutory penalty under VARA, $150,000 per artwork, totaling nearly $7 million in damages. See Cohen v. G&M Realty L.P., 320 F. Supp. 3d 421 (E.D.N.Y. 2018).The 32-page decision was precedential in several ways. First, Judge Block vindicated street artists everywhere when he determined that these artworks had achieved a level of stature meriting copyright protection; in his analysis, he looked beyond the conventional art world for a group that venerated these works, and in doing so, opened the door for a dearth of unconventional art to receive legal protection. Perhaps most notably, the case was under close observation for its potential to establish a precedent for damages under VARA. Clearly influenced by Wolkoff’s surreptitious behavior, Judge Block’s decision to award the maximum penalty was still shocking. The case would work its way up the appellate ladder until finally being rejected for certiorari by the United States Supreme Court in 2020. The case now signals that VARA rights are not to be treated lightly and foretells the dire consequences that can result from a violation.

The above-mentioned disputes illustrate that moral rights cases are complex, and NFTs could further muddy the waters for judges unaccustomed to the peculiarities of the art market and crypto assets. At the moment, there is nothing preventing unscrupulous actors from minting NFTs of works and selling them as their own despite lack of good title, ownership, or IP rights. For instance, a so-called “market disruptor,” GlobalArtMuseum, carried out a “digital art heist” by creating NFTs of famous works held in top-tier museums, such as the Rijksmuseum. GlobalArtMuseum then placed the NFTs for sale on popular marketplace OpenSea. This was a publicity stunt, but nevertheless left the museums rattled. Similar acts could violate copyright law. Tracking down those responsible could prove complicated and the enforcement of legal remedies is not necessarily guaranteed. Online platforms operate across borders, so it may be difficult to determine which law applies, and countless transactions may occur in the meantime. Moreover, some lawyers are not convinced that NFTs qualify for copyright protection because it is an open question as to whether they are original works of authorship. Artists will need to keep this possibility in mind when minting NFTs and exerting moral and economic rights.

Another issue with NFTs pertains to ownership and the integrity of works. A self-proclaimed group of “tech and art enthusiasts” recently purchased a Banksy print, minted it as an NFT – and then burned the original. The group circulated the video of the burning print on YouTube, stating that “by removing the physical piece from existence and only having the NFT, [this]… will ensure that no one can alter the piece and it is the true piece that exists in the world.” This certainly raises the question of authenticity for NFTs when a physical work is also present; which is the original? If the physical work is mutilated or destroyed, but the NFT survives, how will this affect the damages an artist is entitled to receive under VARA? Hypothetically, Banksy could have a viable cause of action under VARA against the group, as his work is certainly of a recognized stature, but no court has ruled on the matter yet.

Conclusion

What does the NFT frenzy tell us? Art is constantly evolving, and the market is quick to adapt once supply and demand for new forms are established. NFTs are operating as a herald of such change, albeit at a much faster pace than anticipated. But this means that current legal and regulatory frameworks are not equipped to deal with some of the issues related to NFTs, including economic and moral rights. Artists entering the world of NFTs should be aware of these issues and consult legal professionals familiar with the pitfalls in this field. Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to represent and advise artists and collectors creating, selling, and purchasing all types of artwork and collectibles – NFTs included.