by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Aug 13, 2024 |

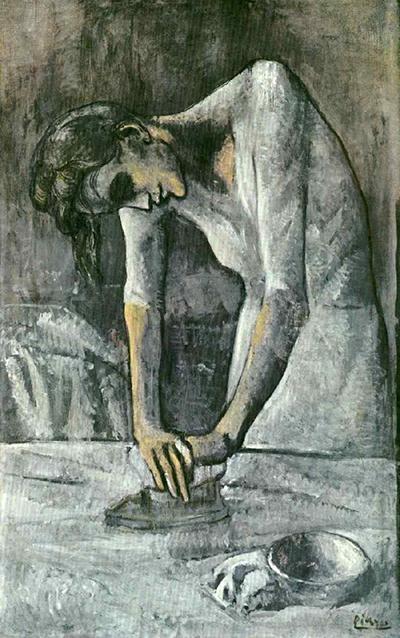

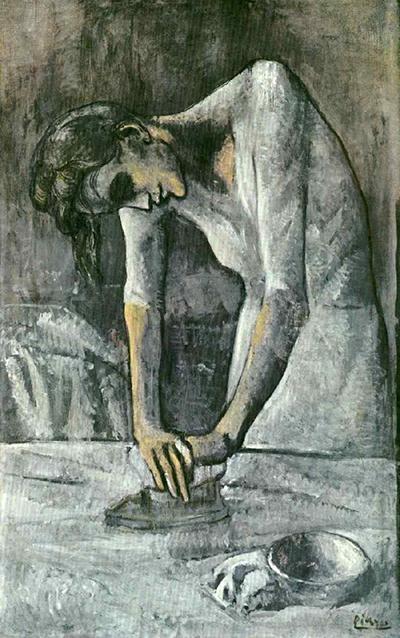

Woman Ironing, Pablo Picasso (1904).

Earlier this summer, Leila A. Amineddoleh was quoted in an article in ARTnews about a recently dismissed case in the Southern District of New York. The dispute involved claims that the painting in question, a Picasso work (Woman Ironing) valued at $150 million, was sold under duress during the Nazi Era.

Unfortunately, courts have not had clear guidance on what constitutes a “duress sale” because judges have been punting that question for years. Thus, Nazi-era cases are often decided on technical grounds, like jurisdictional determinations or time limitations. As Leila predicted last January, Bennigson v. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Found., 1013 N.Y. Slip Op. 24164, one of the most recent Nazi-looted art litigations, was dismissed on technical grounds, namely laches. In Bennigson, the Southern District of New York found that the heirs of Karl Adler (a German Jewish man) had waited too long to file a claim because the family had known about the location of the Picasso painting for decades.

The court granted the Guggenheim Motion to Dismiss, primarily based upon the affirmative defense of laches. Judge Andrew Borrok found that laches is still a relevant defense, even after the passage of the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act (the HEAR Act). The Act was passed to prevent Nazi-looted art restitution claims from being barred on statute of limitations grounds. The court stated, “not only does laches continue to be an appropriate defense [even after the passage of the HEAR Act]…, it may also be resolved as a matter of law at the motion to dismiss stage where the original owner’s lack of diligence and prejudice to the party currently in possession are apparent.” The court cited a number of recent cases, stating, “The HEAR Act explicitly precludes application of “defense[s] at law relating to the passage of time” but does not interfere with the application of defenses at equity, such as laches (Pub L. No. 114-308, 130 Stat. 1524, § 5[a]; Zuckerman v Metro. Museum of Art, 928 F3d 186, 196 [2d Cir 2019]; Reif v Art Inst. of Chicago, 2023 WL 8167182, at *1 [SDNY Nov. 24, 2023], reconsideration denied sub nom. Timothy Reif, et al., Plaintiffs, v The Art Institute of Chicago, Defendant, 2024 WL 838431 [SDNY Feb. 28, 2024]). The court found that the heirs had demonstrated “over 40 years distinct lack of diligence in not raising any concerns.”

However, while the court dismissed the matter based on laches, the opinion ultimately does address duress as a secondary basis for dismissal and it provides guidance for future disputes. Here, Judge Borrok found that the Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint failed to allege any actionable duress under NY law. Amongst other considerations, the opinion pointed to a letter from the Guggenheim to Eric Adler (the eldest son of the seller, Karl Adler). The museum’s letter explained that it was researching the provenance of the painting as it was preparing a catalogue for a collection within the institution. In response, Eric Adler confirmed that the painting was purchased by his parents in 1916 and sold in 1939, but he did not allude to a duress sale or anything else concerning the disposition of the painting. There was no reference in his letter to demanding the restitution of the painting. This, among other reasons, led the court to find that the sale was not made under duress.

Still, the court acknowledges the horrors of WWII and extensively quotes language from the Amended Complaint that recounts the tragedies that occurred during that period. One particularly heartbreaking paragraph was:

“On September 15, 1935, with the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws (“The Laws for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor”), the Nazis consolidated and extended the existing exclusionary measures against Jews. The Nuremberg Laws deprived all German Jews, including Karl and Rosa, of the rights and privileges of German citizenship, ended any normal life or existence for them and relegated them to a marginalized existence, a pivotal step toward their mass extermination.”

While dismissal of Bennigson was primarily based on laches, the court also took the opportunity to examine the duress claims and it provide guidance for future litigations involving Nazi-era takings and war-era transactions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 2, 2022 |

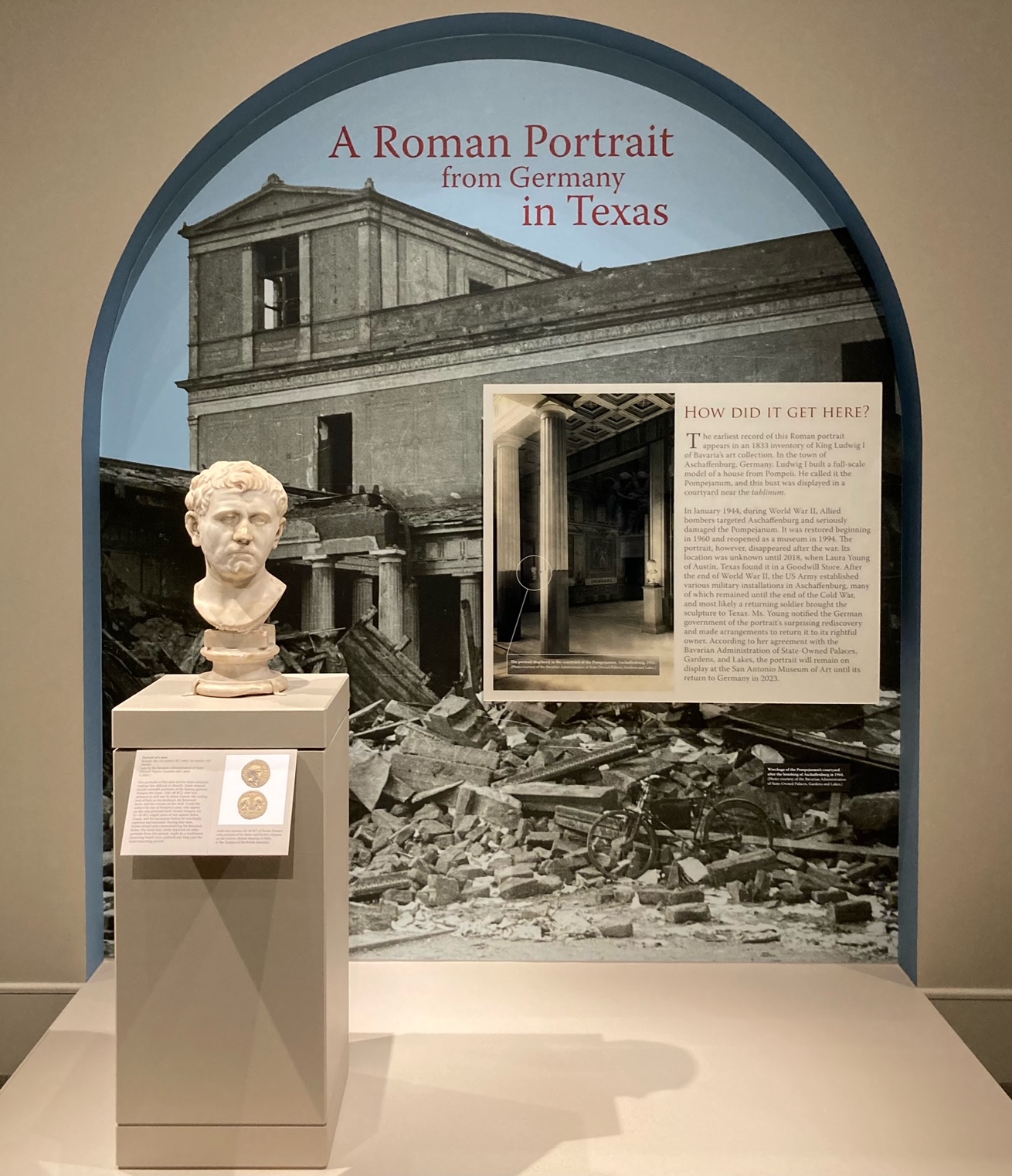

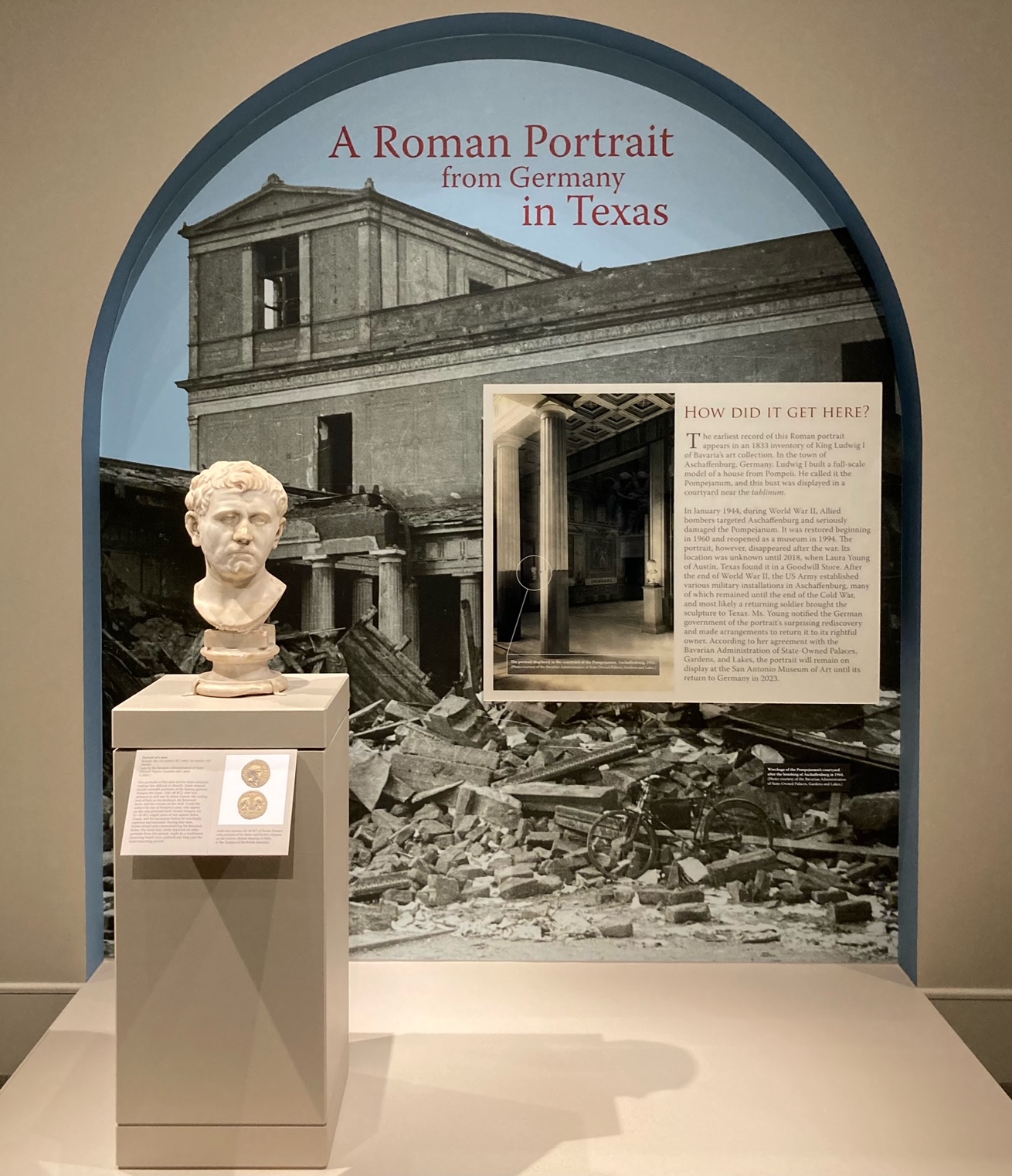

The Marble Bust found in Texas that will be returned to Germany

Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to announce its role in a recent antiquities matter, whereby a Roman marble bust looted during WWII will be restituted to the Bavarian government in Germany. Below, we share details about the bust’s provenance, examples of other cultural objects looted during World War II, the vital work by experts in establishing provenance, and our role in this important cultural return.

I. HISTORY OF THEFT DURING WWII

Much of the literature about WWII-era looted art focuses on thefts perpetrated by the Nazi Party. The Nazis pillaged on a continental scale – appropriating about 20% of all art in Europe at the time. They were notorious for confiscating artworks they deemed “degenerate,” although other works of art were also swept up in their violent mass seizures. One example is the extensive Czartoryski family collection from Poland, which included Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci (later recovered) and a portrait of a young man by Raphael (still missing). After the occupation of Paris in 1940, over 20,000 looted works were taken to the Jeu de Paume gallery, and were kept in a place known as “The Room of the Martyrs.” While Hitler and high-ranking officials had first pick of the loot, German officers could later select masterpieces of their choice. The remainder were slated for destruction, but some evaded this fate thanks to the efforts of art historians and the famed Monuments Men (this title is a misnomer, as this group of British and American members included women).

Looting is often a crime of opportunity, and soldiers on all sides of a conflict may take advantage of the situation by partaking in the appropriation of stolen valuables. Allied soldiers during WWII were no exception. Some of the goods pilfered by Allied troops, like cigarettes and household goods, are relatively inexpensive or nearly worthless by today’s standards. But others – including paintings, rare coins, historic photos, musical instruments, and antiquities – possess great artistic and cultural value. Those valuables continue to be found to this day, sometimes in surprising locations. Some have been returned to the heirs of the original owners while others are involved in ongoing litigation.

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer

In one instance, a member of the U.S. Army stole a collection of medieval religious objects that had been hidden in a cave for safekeeping during the war. The soldier mailed these priceless artifacts home to his family in Texas. These items, known as the Quedlinburg Treasure, included a jeweled 9th-century manuscript written entirely in gold (the Samuhel Gospel). Decades later, the soldier’s heirs reached an agreement with Germany and returned the items in exchange for $2.75 million. Another case involved a pair of portraits by Albrecht Dürer stolen from a museum in East Germany during the war. These were taken by an American serviceman and later bought by a New York collector, Edward Elicofon, for $450. Although Elicofon was purportedly unaware of the paintings’ provenance, a friend recognized the works from a book on art stolen during WWII. After the museum filed a lawsuit in New York, the court compelled Elicofon to transfer ownership and possession of the works back to Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar (Weimar Art Collection).

Perhaps the best-known case involves Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as the Woman in Gold. This gilded painting was forcibly seized by the Nazis after the owners, a Jewish family, were forced to flee Austria in fear of their lives. The portrait is called “the Mona Lisa of Austria.” Along with other works from the Bloch-Bauer’s collection, the portrait wound up in the Austrian State Gallery, but the heirs to the estate fought to recover their family’s lost property. Eventually, after litigation in the U.S. and arbitration in Austria, the Bloch-Bauer heirs succeeded. The dramatic tale became the subject of a film starring Helen Mirren as the main claimant, Maria Altmann, and the painting was later sold in 2006 for $135 million – a record price at the time.

II. AN ART LOVER DISCOVERS THE MARBLE BUST

Not all art and heritage restitutions involve contentious battles. The most recent example of a voluntary return of valuable WWII-looted art can be found in the just-announced agreement between Germany and our client, Laura Young.

The Marble Bust safely strapped in Ms. Young’s car with a seatbelt

Ms. Young happened upon the Marble Bust in the unlikeliest of places: a goodwill thrift shop near her home in Austin, Texas. She purchased the artifact and immediately realized it was more than it appeared to be. The 52-pound Marble Bust, standing at 19 inches tall, was in fact an extremely valuable antiquity. After she drove the Marble Bust home (responsibly strapped into her car with a seatbelt), Ms. Young began digging into its past and discovered the remarkable nature of her find.

Ms. Young later confirmed that, unbeknownst to the goodwill thrift shop owner, the Marble Bust depicts famed Roman commander Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, known simply as Drusus Germanicus or Drusus the Elder. She went on to discover that the Marble Bust has a significant provenance, including links to royalty.

The Marble Bust’s Provenance

- A Roman Marble Portrait Head of Drusus Germanicus (early 1st century AD)

- Acquired by King Ludwig I of Bavaria (before 1833)

- Exhibited in the Pompejanum, Aschaffenburg, Germany (presumably by 1848)

- Stolen during WWII (1944 or 1945)

- Consigned to a goodwill shop in Austin, Texas (Unknown date)

- Purchased by Laura Young (2018)

- Title transferred to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes) (2021)

- Loan to the San Antonio Museum of Art (2022-2023)

A Bit of Roman History

To truly appreciate the richness of the Marble Bust’s provenance, a bit of history is required.

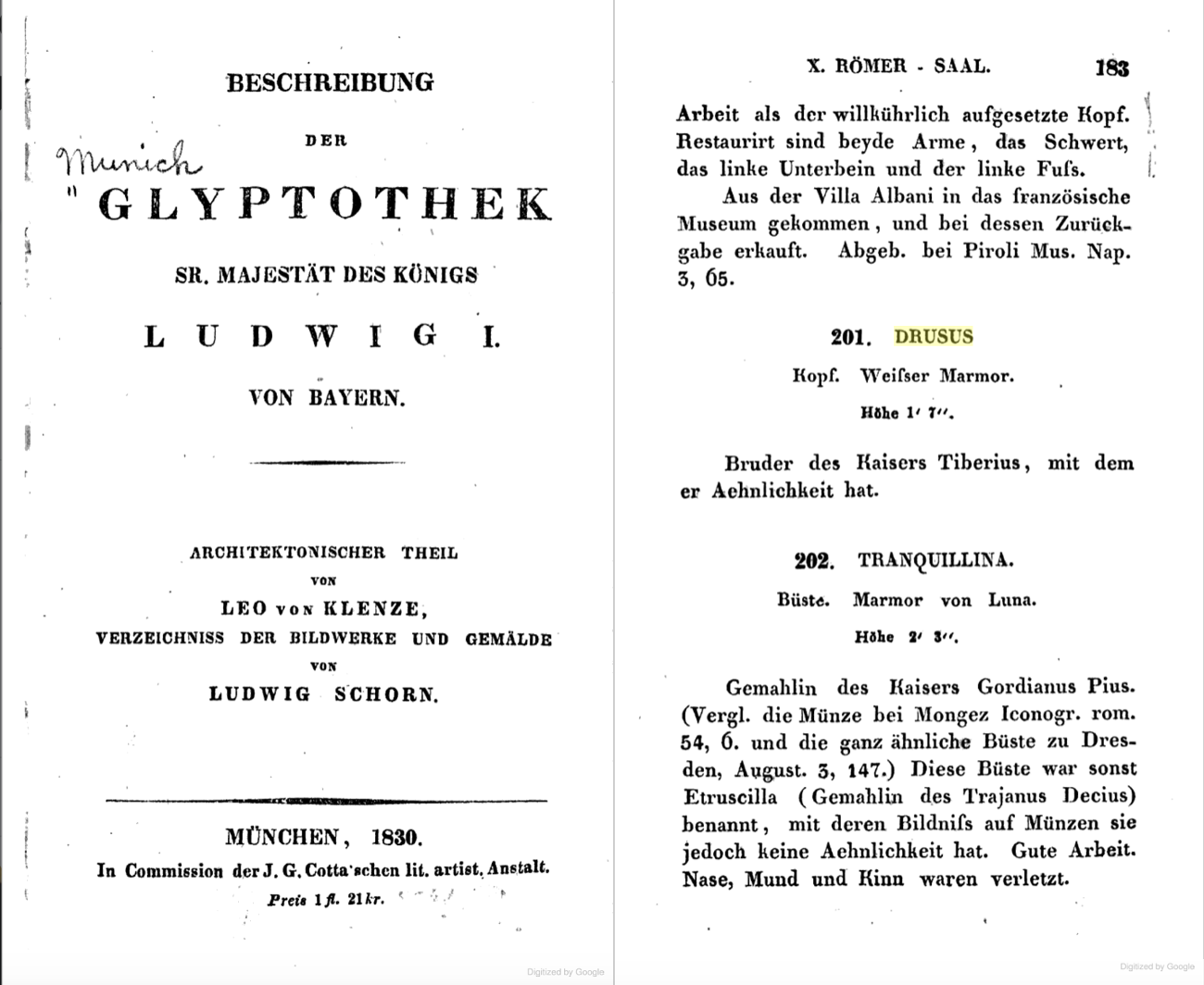

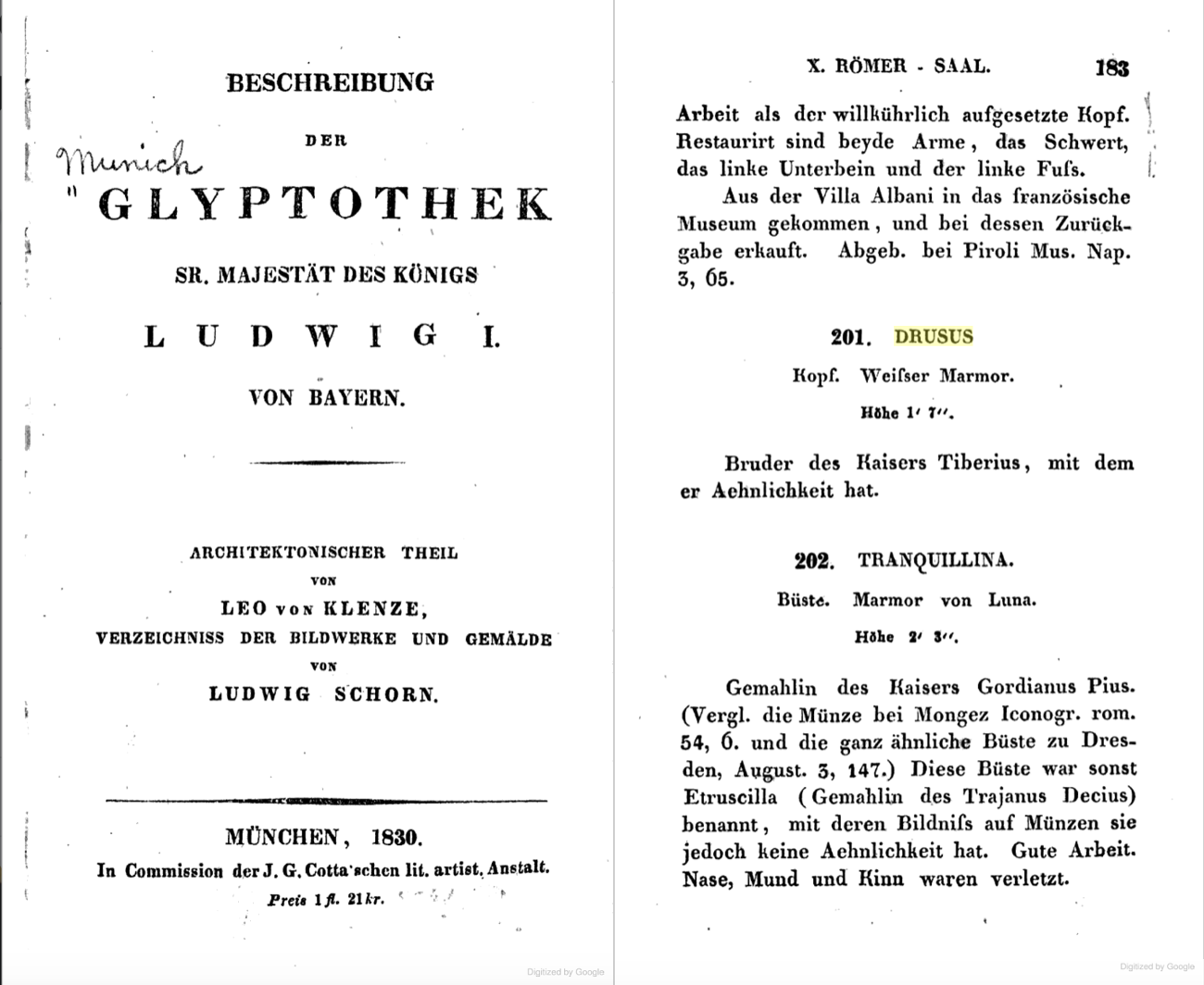

Left, cover of 1833 catalog of King Ludwig I’s antiquities collection , right, description of Drusus (the Marble Head) listed in the catalog

Image from google books digitized version of the catalog

Born on January 14, 38 B.C. to Livia Drusilla and Tiberius Claudius Nero, Drusus Germanicus was the legal stepson of Livia’s second husband, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus and great-nephew of Julius Caesar). Drusus was born shortly after his mother’s divorce, and his mother immediately married Octavian, who historians suspect was Drusus’ true father. Drusus Germanicus eventually became the commander of the Roman forces occupying the German territory between the Rhine and Elbe Rivers. In 9 B.C., Drusus reached the Elbe River, but he was thrown from his horse and died 30 days later from the injuries he sustained. For his conquest of Germania, he received the posthumous honorific title “Germanicus.” The Marble Bust of Drusus Germanicus traveled to Germany nearly two millennia later after its acquisition by the King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, at some point prior to 1833.

Although Drusus was lesser known than some other members of his family, portrait heads of this figure are rare (perhaps due to Drusus’ early death) and highly prized.

Ludwig I and the Pompejanum

After its acquisition by Ludwig I, the Marble Bust was transferred to a most fitting location – the Pompejanum. The Pompejanum (or Pompeiianum) is a replica of a Roman townhouse in Pompeii. Overlooking the Main River in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg, the museum was already a popular tourist destination in the 19th century. The Pompejanum was commissioned by Ludwig I, who was inspired, like many cultural enthusiasts, by the excavations at Pompeii.

Ludwig I was both an art lover and a great patron of the arts. During his reign from 1825 through 1848, he commissioned major museums and art projects throughout Bavaria and the rest of Germany in a bid to elevate Munich to the status of rival European art capitals, like Rome and Paris.

His passion for art was first awakened on a trip to Italy from 1804 to 1805. After that trip, the future king became a voracious collector. Much like today’s collectors, he sent agents across Europe to acquire masterpieces. (One of his art dealers, Johann Martin von Wagner, was noted for his unerring eye, scholarly talent, and great commercial aptitude.) With an unlimited amount of money to draw on from his royal coffers, Ludwig I scooped up many highly sought-after pieces. To display his massive collection, Ludwig I commissioned the construction of a number of major museums. One of his first projects was the Glyptothek, which was used to house ancient sculptures. Another, the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities), was designed in 1848. The works from that institution formed part of the extensive collection of the Bavarian Royal Family.

Ludwig I’s taste in art also ventured beyond the ancient world. In 1836, he created the Alte Pinakothek, the largest museum in the world at the time of its inauguration. Ahead of his time, Ludwig I also established one of the first contemporary art museums in the world–which was unfortunately destroyed by bombing during WWII.

Ludwig I had a deep appreciation for ancient masterpieces and structures evoking the classical era. Projects inspired by this passion include the Propylaea, a monumental city gate constructed as a copy of the Athenian Acropolis and ultimately dedicated as a memorial for Ludwig I’s son Otto, who ascended to the throne of Greece in 1832. It was financed by Ludwig I’s private resources after his abdication, and serves as a symbol of friendship between Greece and Bavaria. While he was still a young crown prince, Ludwig I conceived the project of Walhalla, a temple erected to honor famous Germans. This hall of fame honors nearly 200 laudable people spanning 2,000 years of German history, including both male and female politicians, sovereigns, scientists, and artists, from Albrecht Dürer to Sophie Scholl. Although it is named after the Norse mythological heaven for warriors, the temple was built in the Greek Revival Style and modeled after the Parthenon. The temple continues to be used today, and 19 busts, including one of Albert Einstein, have been added to the collection since WWII.

Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Germany, as restored today

© Carole Raddato (owner of Following Hadrian)

Ludwig I also aspired to bring a bit of ancient Rome to Bavaria. As such, he commissioned the Pompejanum, mentioned above, which was constructed between 1840-1848. Designed by architect Friedrich von Gärtner, it was loosely modeled on the House of the Diosuri (Casa dei Dioscuri) in Pompeii. The villa was never intended to be used as a residence; rather, it has always served as a museum. Located near Schloss Johannisburg (one of Ludwig I’s residences), the king could admire it from his window and make frequent visits. Completed with a Mediterranean-style garden and filled with reproductions of mosaics, architectural forms, and artifacts, the king could escape to Italy with just a short trip to the Pompejanum.

Visitors came to the Pompejanum because it was, and perhaps still is, the most accurate reconstruction of a Roman villa in the world. The ground floor features an entrance hall, the guest room, the kitchen, the dining room, and atrium, all organized around two courtyards. The interiors were painted in the Pompeiian fresco style, and the floors feature copies or adaptations of ancient works and Roman mosaics. The collection included Roman marble sculptures, bronze statuettes and glasses, and household items, as well as two god’s thrones made of marble.

Destruction of the Pompejanum

The Pompejanum destroyed after WWII bombings

Sadly, as often happens during conflict, the damage to the museum’s physical structure led to the loss of its collection. The Pompejanum and the surrounding areas were heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1944 and 1945. Some of the museum’s objects survived bombing only to be looted. But nothing looted from the museum was ever sold by the museum or German government, and thus title to any looted property remained with the Bavarian State. Under U.S. common law principles, valid title to artwork cannot be transferred through looting. There must be a legitimate transaction for title to vest legally in a subsequent purchaser. This means that the Bavarian State continues to maintain a legal claim of ownership over objects that were taken from the Pompejanum.

The Pompejanum Today

The Pompejanum was eventually restored during several phases, the first beginning in 1960. The restoration was completed in 1994, and the villa reopened to visitors that year as the museum of the Bavarian Palace Department and the State Antiquities Collections. Today, it is open to visitors from the spring through the fall.

III. AN ART EXPERT ILLUMINATES THE MARBLE BUST’S PROVENANCE

Establishing the provenance of artwork and antiquities is essential, particularly for objects displaced during times of conflict. It is important not to underestimate the role of art experts in determining provenance, as well as the return and restitution of looted objects. Due to their specialized knowledge and access to resources that are not necessarily available to the public, art experts play a crucial role in establishing the provenance of works and alerting owners to potential red flags. It is always important for purchasers of artwork with unclear provenance or gaps in the chain of ownership to consult experts and ensure that title has been properly transferred.

This pre-war-photo shows the Bust, together with another (today in the Antikensammlungen), standing in the Atrium at the entrance of the Tablinum.

To research her new-found treasure, Ms. Young contacted Sotheby’s. The auction house’s consultant researcher in Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, Jörg Deterling, identified the subject of the Marble Bust as Drusus Germanicus and alerted Ms. Young that the work had gone missing from the Pompejanum decades ago. Before being looted, the Marble Bust had been displayed in the Atrium, at the entrance of the Tablinum that led to the Pompejanum. Although the exact path of the Marble Bust from Bavaria to Texas is unknown, it is safe to assume that it was looted either by an American serviceman who brought it back to the U.S. or by someone who eventually sold it to an American, likely during WWII or immediately after the end of the conflict.

According to Sotheby’s, Mr. Deterling has been “responsible for many returns, restitutions, and repatriations over the years, but his name has never appeared anywhere in connection with them.” Here, he once again played an instrumental role in the return of a valuable artwork by informing Ms. Young about the historical significance and provenance of her find.

IV. AMINEDDOLEH & ASSOCIATES HELPS MS. YOUNG RESTITUTE THE MARBLE BUST TO GERMANY

Drusus Germanicus on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art

After being informed of the Marble Bust’s provenance, Ms. Young worked with Amineddoleh & Associates to voluntarily transfer title to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes), a government agency in Bavaria, Germany. As part of the restitution agreement, the Bavarian agency committed to loaning the Marble Bust to the San Antonio Museum of Art where it is expected to remain on view until its scheduled return to Germany in 2023.

Rather than sell the Roman bust on the antiquities market, where she could have made hundreds of thousands of dollars, our client instead chose to act ethically and return the bust to its rightful home. We worked with Ms. Young to communicate with German authorities, negotiate the transfer of title, ensure proper acknowledgement of Ms. Young’s actions, and request the work’s temporary display in Texas where its story and our client’s role could be further relayed. The Marble Bust’s journey is an extremely important story to tell. It reflects our passion for the past and collecting, the value of museums in providing access to heritage and knowledge, the unfortunate displacement and destruction of national and cultural heritage during conflict, and the hope that people and institutions will choose to act ethically and protect our shared heritage.

In fact, earlier this week the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced the return of a looted marble sculpture to Italy. As in the case with Drusus Germanicus, the object was likely stolen during WWII. The MFA had purchased the antiquity from a Swiss dealer in 1961 for $750. Other records of its whereabouts prior to the purchase are lost, but the dealer had represented that the object originated from Rome. Unfortunately, the MFA’s sculpture had suffered significant damage, such as the loss of facial features, including its nose, mouth and lower left cheek. The Boston museum worked with the Italian Ministry of Culture to effectuate the return of the looted antiquity.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to represent clients who value cultural heritage and consult us in matters involving provenance, authentication, ownership, and restitution. In doing so, they help ensure that cultural heritage is protected and safeguarded for current and future generations while being shared with as many people as possible. Thank you to The Art Newspaper for sharing details about this story HERE.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 25, 2022 |

Armed conflict comes with multiple casualties, the most upsetting of which is the loss of human lives. However, the loss of cultural heritage is also significant. As history has shown on multiple occasions in recent years, notably in the case of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001, invading forces often destroy cultural heritage as a precursor of violence to come and as an intimidation tactic against local populations. Moreover, museums and other cultural institutions are subject to looting and theft during wartime. The Museum of Baghdad suffered such a fate in 2003, when it was ransacked for 36 hours, resulting in the loss of over 15,000 treasures. Thanks to recovery efforts spearheaded by law enforcement and U.S. forces, many of these objects have been tracked down and returned. But the situation remains precarious for Ukraine in the wake of Russia’s attack this week.

Motherland statue at the World War II Museum in Kyiv.

Photo Credits: REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko (taken by drone).

In the days leading up to Russia’s invasion, many art directors worried about the protection of Ukrainian museums and their collections. In particular, museum professionals expressed concerns over the potential destruction of arts institutions as air raids began, especially those in regions at high risk of attack. Institutions such as the Museum of Freedom, the National Art Museum of Ukraine, and The National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War are all located in Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, which is vulnerable to attack and currently the site of clashes with the civilian population. Representatives of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War expressed concern not just about being a casualty of the incursion, but anticipated that the notable Motherland monument outside the building was a possible target. Museum directors also fear that items in their collections promoting democracy and critically portraying the 2014 Russian conflict may face targeted destruction by Russian troops.

Before reaching Kyiv, museums near Russian entry points into Ukraine, including Odessa and Kharkiv, were victims of military attacks. For instance, the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography was bombarded throughout the day on February 24. While most of its collection has been kept safe in Germany while the museum has been under renovations, remaining items are still vulnerable to damage, destruction, and theft.

Map of the reported fighting on February 24 in Ukraine, including Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odessa.

Photo Credit: The New York Times

Many museums in the country have been left with limited options to protect their works. In anticipation of a possible invasion, Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture issued guidelines for the protection and evacuation of museum collections. However, there has not been much discussion of, or planning for, the protection of cultural heritage in the event of an invasion. Even when fully prepared, the evacuation of these collections is difficult. Packaging, crating, and shipping large collections is a costly endeavor that is not always included in museum budgets, particularly if public funds for the arts and culture sector have been depleted (such as COVID-19 recovery efforts). While some museums choose to send their most prized works abroad for protection, these works are still vulnerable to air attacks. Once Russian troops arrived in Ukraine on Thursday, on-the-ground evacuations were precluded because roads were blocked by fleeing civilians.

As a result, many museums were left to enact safety measures within the buildings themselves. Odessa Fine Arts Museum Director Aleksandra Kovalchuk stated that the museum staff was doing what it could to protect its collection of more than 10,000 objects. This included storing works in the basement and installing extra security measures, such as barbed wire barriers. Similarly, the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War worked to move its most important works to a safe location.

Other museums, like the Museum of Freedom, started the process in advance of the conflict. Unfortunately, as a state museum, it needed prior approval from the government to physically remove any works from the premises. Museum Director Ihor Poshyvailo stated that the institution was forced to place important works in storage with museum staff members, who have taken turns guarding the collection. This may be a temporary measure, as Poshyvailo and other staff members could be recruited after President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine called on all able-bodied men under 60 in the country to fight.

Protestors in Odessa holding Ukrainian flag

Photo Credit: Oleksandr Gimanov/AFP via Getty Images

In addition to protecting the works in museum collections, some directors dedicated their efforts to raising international awareness about the risks to people, cities, and cultural heritage in Ukraine. The Director of the Mystetskyi Arsenal National Art and Culture Museum Complex in Kyiv, Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta, released an appeal for solidarity to the museum’s international partners. While Ostrovka-Liuta has since been evacuated to a bomb shelter, in her letter she called attention to the fact that “We should be preparing now the Book Arsenal to be held in May, exhibitions, and cross-sectoral projects — instead our team focuses the efforts to ensure the safety of our staff, our families, as well as to guard our collection, museum objects (paintings, graphics, fine art), including the artworks by Malevych, Yermylov, Bohomazov, Petrytskyi, Zaretskyi, etc., works of modern art, archaeological finds, and the Old Arsenal building, which is a historical and architectural monument of national importance.”

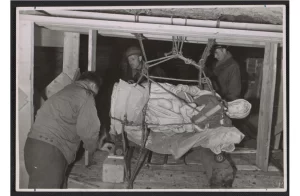

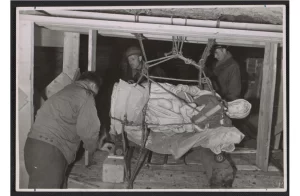

Ukraine’s struggles follow a long history of cultural heritage being damaged during conflict. Perhaps the best known and largest scale of looting and destruction took place during WWII. Countless items were forcibly taken from their owners and are still missing today, although there have been massive efforts to recover them since the end of the war. The Monuments Men were a group of 345 service members that significantly contributed to this effort. Between 1943 and 1951, the Monuments Men sought to track down and recover works that were stolen during the war. The service members of this group were able to recover over 5 million lost or stolen cultural objects.

Since WWII, many other countries have faced similar loss and destruction to their cultural heritage. Notably, the conflicts in Syria and Iraq over the past decades have left an insurmountable number of cultural heritage objects and sites destroyed, damaged, and looted. Today, scholars are still piecing together the extent of the cultural heritage that has been lost. Neither is Ukraine a stranger to this kind of destruction. During the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine lost dozens of cultural and artistic collections. The Donetsk Regional Museum of Local HIstory was hit by anti-tank missiles a total of 15 times, destroying around 30% of their collection. Similarly, during the Maidan revolution, the National Art Museum of Ukraine was at the center of a battle between riot police and insurgents, leading to museum staff taking refuge in the building for many days in an effort to protect the works inside.

Monuments Men transporting a sculpture by Michelangelo, July 9, 1945. Photo credit: Thomas Carr Howe papers, Archives of American Art

Countries continue to fall victim to war, but measures have been established to safeguard art and culture. Primarily in response to the destruction and looting in war zones like parts of Syria and Iraq, there was an urgent need for such protective measures. In October 2019, the U.S. Army Reserve and the Smithsonian joined together to create a modern-day Monuments Men program, in honor of the WWII group. Together, these groups will train service members on how to respond to threats against and preserve cultural heritage. The destruction of cultural heritage has so often been collateral damage in these conflicts, but the creation of the modern Monuments Men program suggests a future in which preservation will be proactively considered and protected.

We hope that the conflict in Ukraine is resolved peacefully and that its people and rich cultural heritage are protected during this tumultuous period.