by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 6, 2020 |

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC co-authored the following blog post with our colleagues at Borghese Associés SELARL in Paris. Borghese Associés, founded in 2009, is a leading business law firm with a boutique art law practice. The firm has a broad art law practice and has handled high-profile art law cases, including the representation of one of Pablo Picasso’s heirs in a case against an art thief convicted of receiving 271 works by the Modern Master. (The case will be featured in our next blog post.) As always, it is a pleasure to work with our esteemed Parisian colleagues.

Vincent van Gogh as a Frequent Target

Singer Laren Museum

March 30, 2020 marked the 167th birthday of celebrated Dutch Impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh. For the Singer Laren Museum near Amsterdam, however, that day was not a cause for celebration. Perhaps taking advantage of the museum’s recent closure due to the global health crisis, unidentified criminals infiltrated the premises and stole one of the artist’s paintings, The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen in Spring (1884). The thieves entered by simply breaking the glass door of the public entrance. They were in and out of the building within a matter of minutes. While this smash-and-grab triggered the alarm, the police arrived too late to prevent the thieves from absconding with their prize. Since the painting, on loan from the Groninger Museum, was the only van Gogh work stolen in the swift theft, it was likely a specific target, rather than being the victim of a crime of opportunity. The painting is valued at approximately €1.5 million, and after worldwide press coverage about the crime, the painting cannot be sold on the open market.

Van Gogh’s works are hugely popular amongst art lovers. Unfortunately, they are also popular with thieves. The painter’s works are often targeted by the latter, particularly in the Netherlands. Over the past thirty years, a total of twenty-eight paintings were stolen on six separate occasions. Luckily, all of them were recovered. However, that is not the norm for stolen art. Typically, stolen works are never seen again; the recovery rate for stolen art and prosecution of the related criminals is estimated to be between 5 and 10% worldwide. Pilfered works often vanish on the black market and may later re-emerge in private collections. Other times, thieves destroy the works out of fear that the art will serve as evidence for their criminal missteps.

Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen (1884-1885)

Notably, two paintings were stolen from Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum in 2002. During the early morning hours of December 7, 2002, Octave Durham climbed a fifteen-foot ladder and used a sledgehammer to break a window to enter the Van Gogh Museum. He was able to pass by the infrared security system, cameras and roaming guards. Two paintings, View of the Sea at Scheveningen (1882) and Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen (1884-1885), were lifted from the walls, and the thief escaped using a rope with the help of accomplice Henk Bieslijn. The entire process took only three minutes and forty seconds. Unfortunately, neither work was insured at the time, and they were both on loan from the Dutch government. It is significant that in this instance, Durham did not target the paintings specifically, but rather took advantage of an opportunity to gain access to the museum premises and removed the works because they were the smallest and easiest to carry.

However, this specific theft was particularly upsetting because the subjects depicted in the paintings added both sentimental and financial value to the works. The painting of Scheveningen is one of the only two seascapes that van Gogh ever painted. Because it had never entered the art market, it is virtually impossible to properly quantify its worth. The other painting, showing the church in Nuenen, is also remarkable because the church is where van Gogh’s father worked as a pastor. After his father’s death, van Gogh added the mourning figures in black, and gave the painting to his mother as a gift.

Many thought that the stolen paintings were lost forever. Usually, if a work is missing for ten years, there is a very small chance of it ever returning home. However, in September 2016, the works were found in Italy, in the home of a mobster’s mother. The paintings were recovered by the Carabinieri during an investigation of the Amato Pagano clan of the Camorra Mafia family, a group associated with international cocaine trafficking. In January 2016, Italian prosecutors arrested several members of the family and criminals associated with them in connection to a drug ring with contacts in the Netherlands and Spain. Additionally, Italian financial police confiscated about $22.5 million worth of assets belonging to the clan. Both of the paintings were damaged and found without their frames. The paint on the bottom left corner of the seascape had broken away and the edges of the canvas of the church scene had minor damage as well. Luckily, no major damage was reported, and the paintings returned to their rightful home.

Museums as Targets: Poor Security and Opportunities

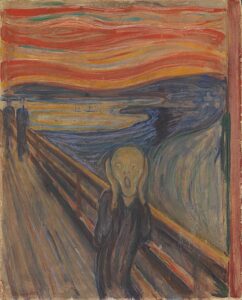

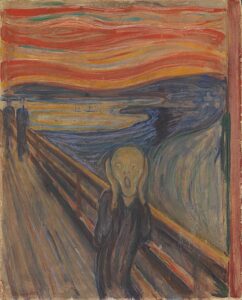

The Scream by Edvard Munch

Museums are often targeted by thieves due to poor security. Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) was stolen in only 50 seconds from the National Gallery in Oslo on the opening day of the 1994 Winter Olympics in Norway. Two thieves were aware that a major world event was occurring nearby and that police would not be readily available to nab them. As a result, they broke into the museum through a window, cut a wire holding the painting, and left a note saying, “Thousand thanks for the bad security!” Another example of an opportunistic art theft was the first major art heist of the new millennium, taking place at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford shortly after midnight as the new millennium was rung in. A £3 million work by Paul Cézanne, View of Auvers-sur-Oise (1879-1880), was stolen in a fashion reminiscent of The Thomas Crowne Affair. Known as the “Y2Kaper,” the thief entered the museum shortly after midnight as the British city was celebrating the new year. As everyone was distracted with millennium celebrations, the burglar gained access to the building from the adjoining Oxford University Library (which was undergoing a renovation at the time) before climbing onto the roof, smashing a skylight, setting off a smoke canister, and then lowering himself into the room via rope. Once he obtained the canvas, which took approximately ten minutes, the criminal vanished into a crowd of revelers. Because this was the only painting removed from the museum, it has been speculated that this was a made-to-order art theft; likely, a private collector or interested party commissioned a criminal to steal the coveted painting. However, it is also possible that the crime was tied to organized crime. Ironically, the museum had increased security in 1992 after a spate of recent robberies, including the theft of various items, such as Greek vases, paintings, silverware, and a 16th century painting that were removed by a visitor who smuggled them out of the museum under his coat. Unfortunately though, the museum failed to take precautions against intruders accessing the museum through the construction structure.

Courtyard at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, MA

The highest profile art theft in U.S. history was perpetrated against the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston during the early morning hours of March 18, 1990. Significantly, the timing allowed the thieves latitude because Boston was in disorder due to the city’s famous St. Patrick’s Day celebrations from the evening of March 17 and into the morning of March 18. The criminals, disguised as police officers, subdued two museum security guards and removed thirteen works valued between $600 million and $1 billion. The stolen items include Johannes Vermeer’s The Concert (1664) (valued between $200 million and $300 million), and Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (the Dutch painter’s only known seascape). The thieves were unsophisticated, tearing the paintings from their frames, likely causing substantial damage. Nonetheless, the criminal scheme was clever enough to succeed and the works have never been recovered. The theft is notorious because neither the paintings nor those responsible have been found, despite the offer of a $10 million award for information. The museum continues to work in partnership with the FBI and the U.S. Attorneys’ Offices in the hope that the artworks will be returned to their frames, which continue to hang empty in their original places. Until that time, visitors of the museum will be confronted with the vacant frames serving as a grim reminder of the unfortunate theft.

In France, an astonishing theft took place in May 2010 at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. Tomic Vjeran, nicknamed “Spiderman,” a well-known art and jewelry thief who was already condemned fourteen times for similar actions, took advantage of a deficient security system to steal five of the most beautiful artworks of the museum. The stolen works, estimated to be worth 50 million euros, were Nature morte au chandelier (1922) by Fernand Léger; La Femme à l’éventail (1919), a portrait of Luna Czechowska, by Amedeo Modigliani; Le pigeon aux petits pois, (1911) by Pablo Picasso; La Pastorale (1906) by Henri Matisse; and, last but not least, L’olivier près de l’Estaque (1906), a work that Georges Braque painted in three other versions.

Before the Tribunal Correctionnel de Paris, Spiderman detailed the robbery; it took six days of scouting and preparing. A bay window was dismantled from the outside and then removed using suction cups. To the astonishment of the police, Vjeran explained that the security system shutdown enabled him to move far beyond his original targets, which were the Fernand Léger and the Modigliani paintings. Investigators discovered that Vjeran had been assisted by two accomplices, a 62-year-old antiques dealer, and a 40-year-old watch expert and repairman. The day after the robbery, the antiques dealer and the Vjeran met in an underground car parking lot in the neighborhood of Bastille to hand over the Léger to a buyer from Saudi Arabia in exchange for 80,000 euros. But two days later, the Saudi buyer’s middleman returned the paintings to the antique shop. The theft was simply too high-profile, making the painting unsellable. Unable to unload the stolen paintings, the antique dealer thought about selling the works in Belgium or Israel, where he believed the laws would be more lenient. He even thought, fleetingly, about giving them back to the city of Paris. In July 2010, he presented the Modigliani painting to a friend, a watch expert, and asked him to store the five stolen paintings at his shop, behind a large cupboard. One year later, the police arrested Vjeran and his accomplices. To this day, no one knows for certain what became of the five missing paintings. Sadly, the works may have all been destroyed. Before the criminal court, the watch expert maintained that he had thrown them away in the garbage in a moment of panic, when he realized that his involvement had been discovered.

There have been other notorious robberies in the history of Paris’ museums. The most famous is the theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s La Giaconda (the Mona Lisa) from the Louvre, on the morning of August 21, 1911. Vincenzo Peruggia, a glazier who had helped fix a protective glass on the masterpiece, found his way inside the Louvre by passing through a hidden door. He managed to steal Mona Lisa, conceal it under his employee’s coat, and bring it back home where it remained hidden under his bed for two years. Peruggia managed to convince the police that he had nothing to do with the theft. During that time, international pressure mounted to find the thief as the scandal spread across the media. As art lovers demanded the return of the masterpiece, Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile flashed across the world, gracing newspapers. In fact, the high-profile theft made the painting the most recognizable artwork in the world. The magistrate in charge of the case sentenced poet Guillaume Apollinaire to prison for a few-day sentence because the poet’s dubious tenant, Guy Piéret, foolishly sold a newspaper the tale of his exploits. These tales included his fictitious theft of the Mona Lisa.

There have been other notorious robberies in the history of Paris’ museums. The most famous is the theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s La Giaconda (the Mona Lisa) from the Louvre, on the morning of August 21, 1911. Vincenzo Peruggia, a glazier who had helped fix a protective glass on the masterpiece, found his way inside the Louvre by passing through a hidden door. He managed to steal Mona Lisa, conceal it under his employee’s coat, and bring it back home where it remained hidden under his bed for two years. Peruggia managed to convince the police that he had nothing to do with the theft. During that time, international pressure mounted to find the thief as the scandal spread across the media. As art lovers demanded the return of the masterpiece, Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile flashed across the world, gracing newspapers. In fact, the high-profile theft made the painting the most recognizable artwork in the world. The magistrate in charge of the case sentenced poet Guillaume Apollinaire to prison for a few-day sentence because the poet’s dubious tenant, Guy Piéret, foolishly sold a newspaper the tale of his exploits. These tales included his fictitious theft of the Mona Lisa.

The truth was revealed in 1913 when Peruggia, under the name of Leonardi, tried to sell the Mona Lisa to a Florentine dealer, Alfredo Geri. When Geri, accompanied by M. Poggi, director of the Gallerie degli Uffizi (the Uffizi) in Florence, saw the painting and realized its authenticity, they alerted the police who arrested Peruggia at his hotel. After a triumphant tour in Italy, the Mona Lisa returned to the Louvre on January 4, 1914. As for the thief, he became a national hero for many Italians, claiming that his actions were motivate by patriotism. For his legal defense, he argued that he had “given back” the painting, and thus could not be condemned for theft. The court rejected the argument, but sentenced him to a relatively lenient sentence of only one year in prison.

Our next blog post with examine art thefts as inside jobs and from private collections.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 27, 2019 |

© Julien Mignot for The New York Times

Last week, the NY Times featured an article about a 17th-century painting discovered behind a wall in a Parisian commercial space. The 10-by-20-foot canvas was discovered during the renovation of an Oscar de la Renta boutique. The mysterious painting is of a 17th-century nobleman and his entourage entering the city of Jerusalem. Through the use of art experts and historians, it was revealed that the work was painted in 1674 by Arnould de Vuez, a painter who worked with Charles Le Brun, the first painter to Louis XIV and designer of interiors of the Château de Versailles. Le Brun, with a reputation for involvement in duels, eventually fled France and made his way to Constantinople.

It is unclear how the canvas found its way to Paris and was hidden behind the wall of the boutique (it’s speculated that it may have been hidden during WWII). But most interestingly, art historian Stephane Pinta expertly traced the painting to a plate that was reproduced in “Odyssey of an Ambassador: The Travels of the Marquis de Nointel, 1670-1680,” by Albert Vandal. The book, written in 1900, recounted the travels of Louis XIV’s ambassador to the Ottoman Court. The discovery of the book, which includes a rotogravure of the rediscovered painting, reveals that the painting is of Marquis de Nointel arriving in Jerusalem.

After discovering the identity of the painting and its creator, the restoration process began. A team of specialists worked to restore the painting to its original state. However, investigators are still working to study the painting, understand its iconography, and trace its provenance and movements from inception through today.

The story demonstrates the importance of thorough provenance investigations. However, this is not the first case involving the discovery of art hidden behind a wall; there are a number of well-known instances involving artistic masterpieces hidden behind walls. Perhaps the most famous hidden work involves Leonardo’s famed “The Battle of Anghiari.” But the work isn’t hidden in the usual way. Some believe it was in place sight, on (not behind) a wall in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. It’s believed that Leonardo’s now lost masterpiece (sometimes referred to as “the Lost Leonardo”) lies beneath a work by Giorgio Vasari. But with the work covered by another intact masterpiece, questions arise as to how to preserve these two dueling artworks.

Works are sometimes hidden due to criminal motivations. Fourteen years after two Van Gogh works were stolen from the artist’s eponymous museum in Amsterdam, officers in Italy’s Guardia di Finanza found the missing works in southern Italy. The paintings were hidden behind a wall in the home of a mafia boss.

Sometimes works are hidden due to family disputes and conflicting claims of ownership. In 2006, Sotheby’s sold a Norman Rockwell painting that had been hidden behind a wall by the painting’s owner. During their divorce, the owner of the work did not want his wife gaining possession of, or making copies of, “Breaking Home Ties.” He hid the painting behind the wall, but his sons discovered the artwork after their father’s passing.

There are a host of other stories involving the discovery of works hidden behind walls, even by the artists themselves. It is always exciting when a work is rediscovered.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 7, 2017 |

A recently recovered painting by Van Gogh

Leila’s curation of the exhibition Art Crime: Looters, Forgers, Thieves & Vandals was featured this week in NYU News’ “A Rogues’ Gallery of Art Crime.” The article discusses Leila’s seminar “Art Crime and the Law,” the first course of its type offered by NYU’s Department of Art History. Like the exhibition, the article examines some of the famous art crimes through history, including illicit activities directed toward fine art, antiquities, and collectibles. The article also reminds the reader that art crimes are usually not committed by dashing Clooney-like thieves (as incorrectly portrayed by Hollywood’s glamorizing of crime), but by gang members, violent criminals, and opportunists.

The histories of the featured works are intriguing (the selected works include some of the world’s most famous art), and the crimes against them are explored in the display, done in collaboration with research completed by students at NYU. The preparation of the exhibition was a great learning tool that now serves as an engaging exploration of art crime for a general audience. The show was slated to close on March 1, but its run has been extended until the end of the semester, due to it popularity. If you are interested in visiting the exhibition, it is now on display on the second floor of the Global Center at NYU (238 Thompson St, New York, NY 10012).

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 17, 2016 |

One of the challenges associated with authenticating art is that it can sometimes be difficult to procure an expert’s opinion. During the past decade, various artists’ foundations have either dismantled or decided not to provide opinions on authenticity. In addition, some experts refrain from providing advice due to fear of litigation. With the exorbitant expense of defending oneself in court, possible damage to a professional reputation, and the stress involved in litigious battles, some experts abstain from involvement in authentication disputes.

However, in the case of van Gogh works, there is a source that willingly provides expertise—the Van Gogh Museum. This week’s publication of a sketchbook purportedly belonging to van Gogh is creating waves in the art world because the author of the text did not confer with the leading van Gogh authority. Rather than present the works to the recognized experts on the oeuvre of the artist, the author of “Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook” excluded the museum’s opinion in the book. However, the museum had repeatedly informed the owners of the sketches that they are not by the Dutch artist. The sketchbook’s anonymous owners approached the museum in 2008 and 2012 and were told that the drawings were forgeries.

However, in the case of van Gogh works, there is a source that willingly provides expertise—the Van Gogh Museum. This week’s publication of a sketchbook purportedly belonging to van Gogh is creating waves in the art world because the author of the text did not confer with the leading van Gogh authority. Rather than present the works to the recognized experts on the oeuvre of the artist, the author of “Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook” excluded the museum’s opinion in the book. However, the museum had repeatedly informed the owners of the sketches that they are not by the Dutch artist. The sketchbook’s anonymous owners approached the museum in 2008 and 2012 and were told that the drawings were forgeries.

The museum has definitively said that the works are fakes for three reasons: forensic anomalies, unclear provenance, and stylistic irregularities. The forensics are wrong—the materials used for the sketches are not the type used by van Gogh. The sketches feature brown pigment, where as Van Gogh used black or purple ink. What’s more, the paper used is different than the type used by the famed artist. The provenance in unreliable, as a source purporting to establish its presence in the 1890s is questionable. And even more damning is the style. The museum asserts that the sketches do not reflect the artist’s style or artistic development during the time they were supposedly drawn. They also feature “typical mistakes.” The museum states that “the person who made them is following the examples of van Gogh in a superficial way and doesn’t know what van Gogh was aiming for.”

However, the academics supporting the van Gogh attribution discuss the sketchbook’s interesting history, and the author of the academic work spent three years examining the work’s history, purportedly tracing it back to a French cafe in 1890.

The recent announcement of the sketchbook draws attention to the art world’s sometimes contentious authentication process, and the inevitable battle of experts that frequently results. However, in a market full of skillfully executed forgeries, it is surprising that any art scholar would not heavily weigh the knowledge of the leading authorities (at the Van Gogh Museum) who were ready and willing to provide valuable expertise. To read more about the authentication process and the history of forgeries, find a copy of my recent academic publication: Are you Faux Real? An Examination of Art Forgery and the Legal Tools Protecting Art Collectors.

There have been other notorious robberies in the history of Paris’ museums. The most famous is the theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s

There have been other notorious robberies in the history of Paris’ museums. The most famous is the theft of Leonardo da Vinci’s