by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Dec 14, 2022 |

In this annual newsletter, Amineddoleh & Associates is pleased to share some major developments that took place at the firm and in the art world during 2022.

LITIGATION AND SETTLEMENT UPDATES

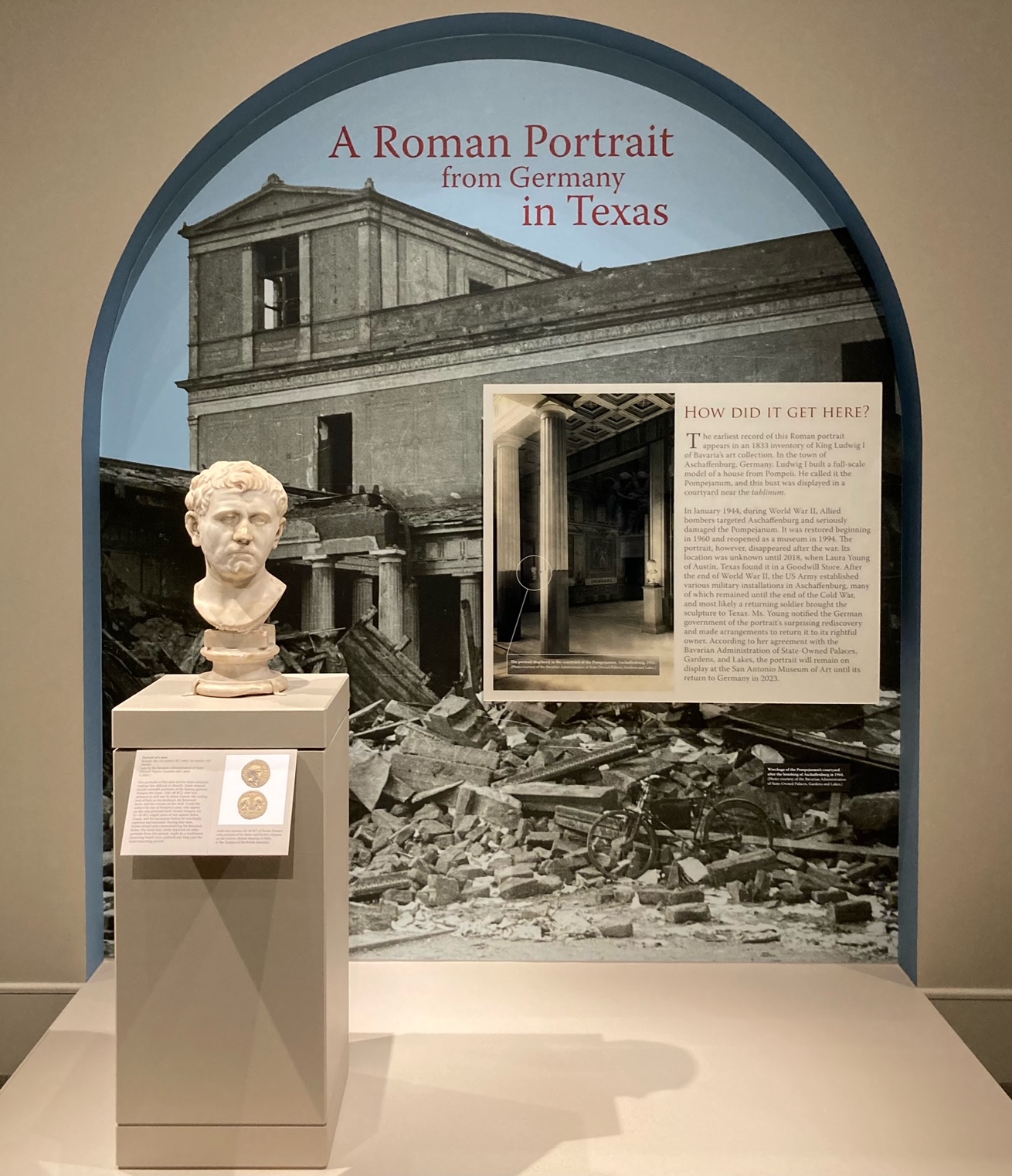

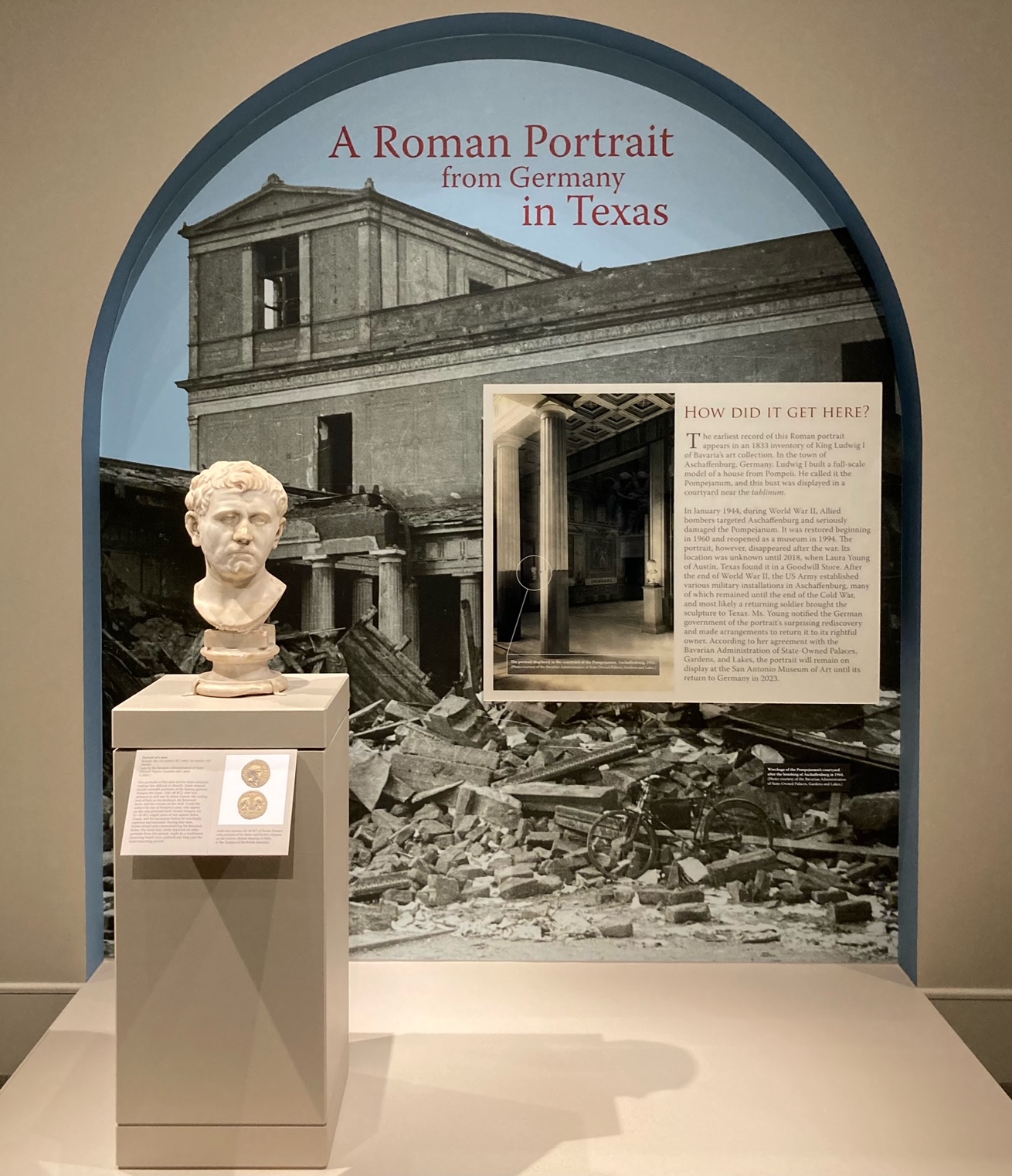

The “Goodwill” Marble Bust

The Marble Bust looted during WWII that was found in Texas and will be returned to Germany

Possibly the most talked about art law matter of the year was the return of an ancient marble bust to Germany. The 2,000-year-old artifact likely originated from Rome, but it was acquired by Bavarian King Ludwig I and then placed in a German museum from where it was looted during World War II. Our client, Laura Young, bought it at a local goodwill shop and ultimately returned it to Germany. It was an honor to advise her and work with her to negotiate the internationally celebrated return.

Copyright Infringement Lawsuit

At the start of the year, we filed a litigation in Iowa on behalf of a muralist, Chris Williams. His work was featured in an advertisement that aired during the Super Bowl. We are currently representing him in a lawsuit for copyright and a violation of his moral rights on the Visual Artists Rights Act.

ART & IP NEWS

One of our favorite things about the art market is that there is always something exciting happening in the art world. Some of our most popular blog posts from this year are found below.

Celebrities and Fossil Collecting

Skeletons in the American Museum of Natural History

In this blog post, our firm examined legal matters involving dinosaur fossils and skeletons, including purchases made by Nicolas Cage, Leonardo DiCaprio, and The Rock. Auction houses have faced growing interest in buyers seeking dinosaur bones. The sales have gotten a lot of attention, perhaps due to the trend of major celebrities making large, public bids for the pieces. As a result of the publicity, countries around the world from which fossils are illegally excavated have presented auction houses with ownership claims, based on their country’s property laws. Copyright law was also an issue for auction houses selling dinosaur skeletons this year because skeletons that are partly comprised of replica bones may come with intellectual property rights in the manufactured pieces.

Fashion Law and Protecting Brands

When does the law protect fashion brands? And what is the cost to other artists? Our firm answered these questions in this posts inspired by the Fall 2022 Fashion Weeks taking place around the world. Prominent fashion designers have been known to incorporate logos of other brands into their designs, often as a part of social commentary. Even where artistry is the intent behind the repurposed logo, these designers face financially devastating intellectual property claims from major the brands and companies who own the rights to the logo. Our firm considered how to balance protecting consumers from consumer confusion with giving designers the artistic liberty to create fashion that sparks social commentary. Read more on our website.

When does the law protect fashion brands? And what is the cost to other artists? Our firm answered these questions in this posts inspired by the Fall 2022 Fashion Weeks taking place around the world. Prominent fashion designers have been known to incorporate logos of other brands into their designs, often as a part of social commentary. Even where artistry is the intent behind the repurposed logo, these designers face financially devastating intellectual property claims from major the brands and companies who own the rights to the logo. Our firm considered how to balance protecting consumers from consumer confusion with giving designers the artistic liberty to create fashion that sparks social commentary. Read more on our website.

New York Raises Holocaust Awareness Through New Law

Gustav Klimt’s Woman in Gold

New York State now requires museums to post which artworks on display have links to the Holocaust. The New York bill, which was signed into law on August 10, 2022, accompanied two other Holocaust related bills aimed to combat rising reports of antisemitism. Our firm revisited the difficulty of proving provenance for items acquired during the Holocaust and shortly following WWII. The restitution of these works to families from which the pieces were stolen is incredibly healing.Unfortunately, such claims for the return of priceless works of art often have to overcome enormous legal hurdles, such as the difficulty of proving provenance in court and FSIA claims brought by countries who now claim possession. Read more on our website.

LAW FIRM UPDATES AND EVENTS

New Team Members

Our firm welcomed two new members to join our team, Yelena Ambartsumian and Maria Cannon. Yelena joins the firm as Counsel, while Maria joins us as an associate. We are proud to have Yelena and Maria as members of our team, and we wish them both a warm welcome.

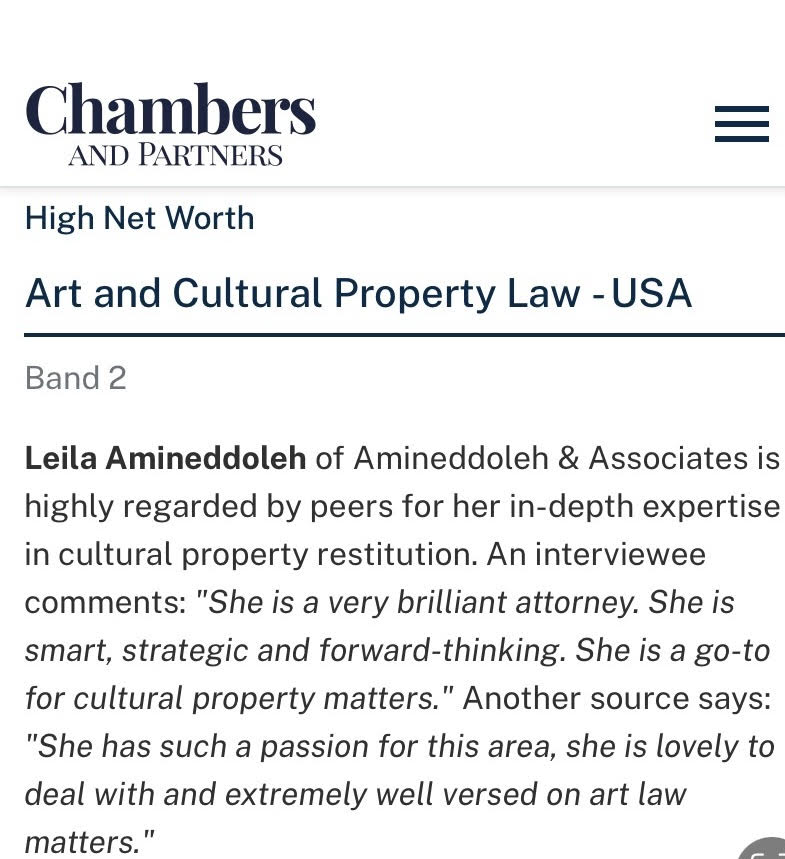

Firm Founder Listed by Chambers

This year, firm founder Leila A. Amineddoleh was recognized by Chambers and Partners High Net Worth Guide for her work in Art and Cultural Property Law. The publication named Leila “a brilliant attorney,” and “a go-to for cultural property matters.” The publication also remarked on her passion for art law and her wealth of experience in the field. Read more here.

Art Law Conferences

Congratulations to our firm’s founder Leila A. Amineddoleh, who successfully chaired the 14th Annual NYCLA Art Law Institute, one of the most anticipated events of the year. Earlier in the year, in March, Leila presented the keynote speech at Yale University’s conference “Dura-Europos: Past, Present, and Future.” The conference focused on the systematic looting of Dura-Europos that took place during the Syrian civil war and during prior millennia. Leila presented on the history of cultural heritage looting and modern efforts to prevent such plunder. Read more about the conference here.

Leila was also a speaker at the Salmagundi Club, one of the oldest arts organizations in the U.S. Her other speaking engagements included moderating a panel for Art Appraisers’ Association Art Law Day and for Fordham’s Intellectual Property Law Journal’s 30th Annual Symposium, “Duplicate, Decolonize, Destroy: Current Topics in Art and Cultural Heritage Law.” In addition, she spoke at conferences hosted by Cardozo School of Law and Notre Dame School of Law. At Cardozo School of Law, Leila spoke on a panel at a symposium discussing cultural property ownership. Read more here. At Notre Dame’s Journal of International and Comparative Law Symposium, she served as panelist at the symposium, “International and Comparative Approaches to Culture”, and discussed antiquities disputes and repatriation of cultural heritage.

Associate Claudia Quinones presented on the “What’s New in Art Law?” panel at the 14th Annual NYCLA Art Law Institute. Her presentation covered title and ownership disputes, new technologies, and climate change activism in the art world. Details about the conference can be found here.

Yelena’s speaking engagements included Fordham Law School’s 30th Annual Intellectual Property Law Journal Symposium as a panelist on “Erased: Protecting Cultural Heritage in Times of Armed Conflict.” She also was a panelist at American University of Armenia’s Center for Truth and Justice Inaugural International Conference, “Cultural Heritage at Stake: How to Preserve, Mitigate Damage, and Punish Destruction.” Read more about the conference here.

IN THE PRESS

Leila appeared in the New York Times a number of times this year, in addition to Artnet, The Art Newspaper, the Observer, the Washington Post, USA Today, People Magazine, and Town + Country Magazine. She discussed a variety of topics, including the art market, cultural heritage disputes, Nazi-looted art, intellectual property disputes, and art collecting practices. Leila also appeared on WPIX-NY and in a number of podcasts.

CLIENTS AND REPRESENTATIVE MATTERS

Sculpture Garden Commission at the Smithsonian Institution

We are very proud to have served as legal counsel to famed artist Hiroshi Sugimoto for a number of his commissions, including his highly anticipated sculpture garden at the Hirshhorn Museum, part of the Smithsonian Institution.

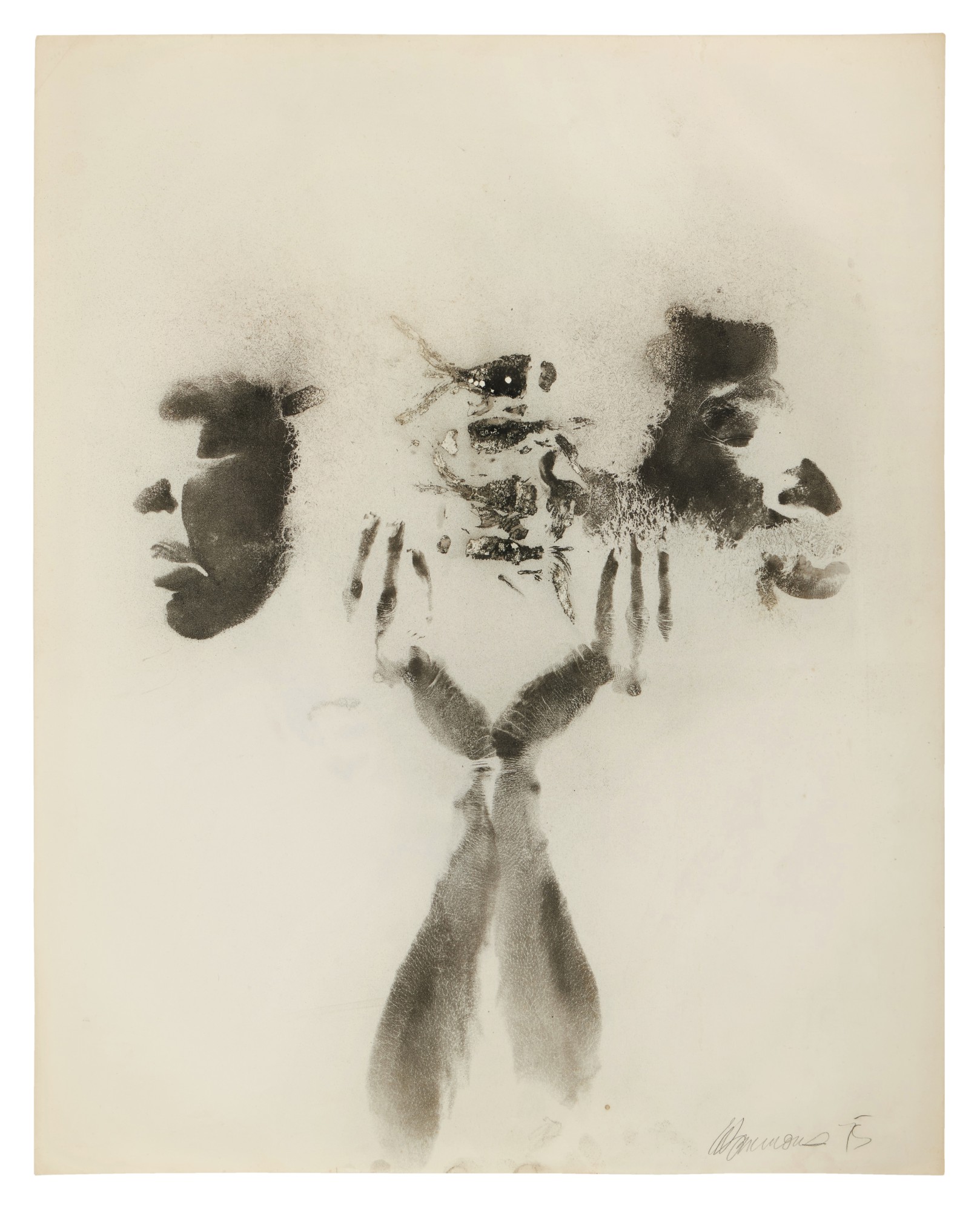

Auction Sales

Auction Sales

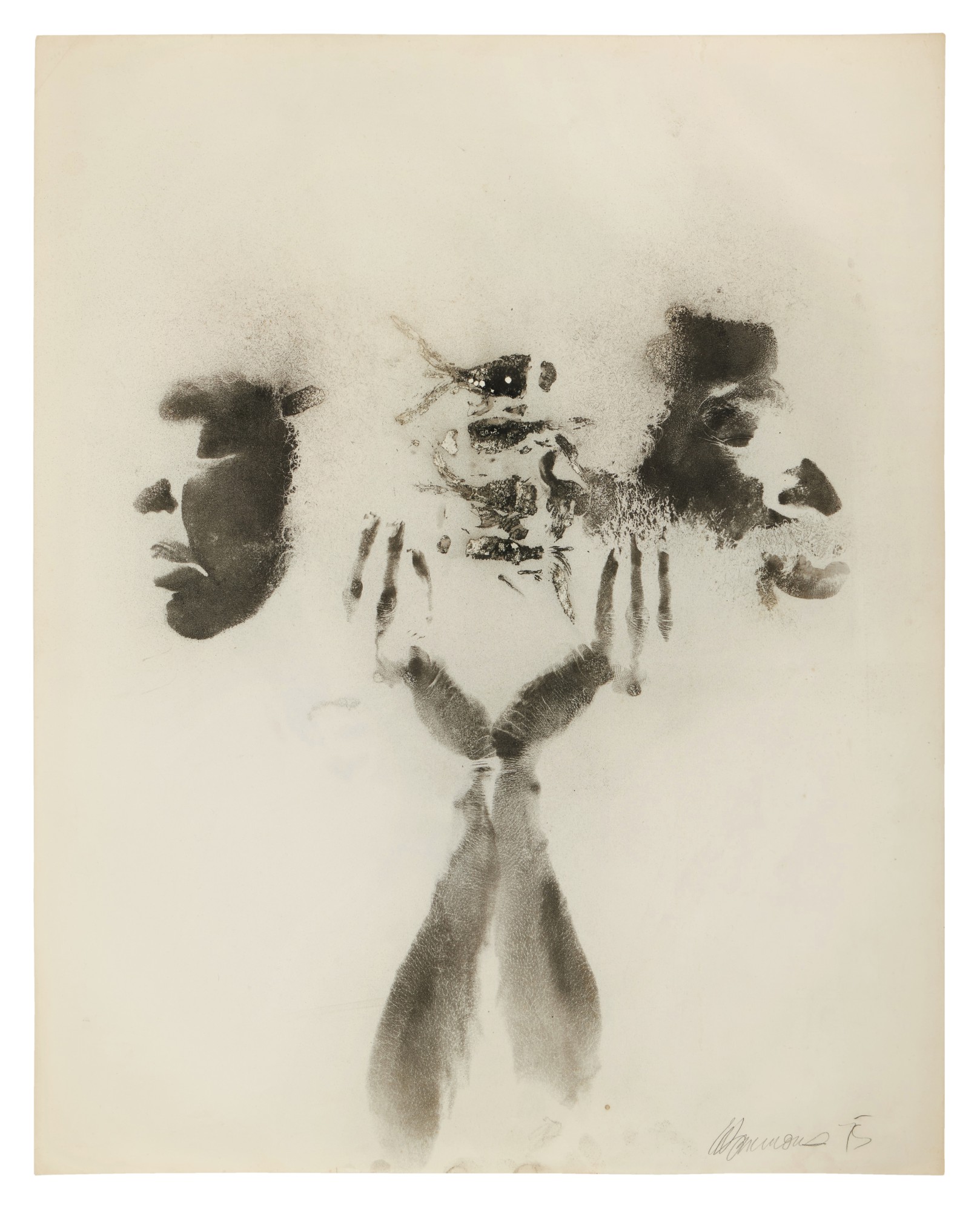

We worked with a number of clients to assist them with consigning art for sale at auction. One of our clients is the collecting family that consigned three works by David Hammons for the Sotheby’s Contemporary Evening Auction and one work at the Contemporary Curated sale earlier in the spring. Sotheby’s touted these works and their provenance, after the paintings remained with our clients for nearly five decades. All four of the works performed well, with two of them selling for above their high estimates.

Trademark Clients

We continue working with brands, artists, and companies by advising and serving as trademark prosecutors. Included among our clients are luxury watch brands, fragrance companies, and musicians, including multi-platinum songwriter and produced Jonas Jeberg.

Advising Art Market Players on New Platforms

While we often work with traditional art market participants (including artists, collectors, foundations, auction houses, museums, art advisors, and art experts), we are also happy to be at the forefront of the art and cultural world. As new art platforms and technologies develop, we are pleased to work with exciting online galleries, NFT platforms, novel art collecting exchanges, and artists exploring new media. We look forward to continue cutting edge work in the art sector.

On behalf of Amineddoleh & Associates, we wish you a happy and healthy holiday season and a wonderful and prosperous new year.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 9, 2022 |

Our founder appeared on Al Jazeera to discuss the return of dozens of looted antiquities from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She discusses the importance of conducting due diligence and proactively researching items in museum collections. The short news segment can be found HERE.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 9, 2022 |

A New York bill signed into law on August 10, 2022 will require museums to provide a notice to viewers if works of art on display have links to the Holocaust. This groundbreaking and restorative legislation accompanies two other Holocaust-related bills signed into law: one aimed at increasing Holocaust literacy through curricula in educational institutions, and the other designed to increase pressure on banks that assess fees related to Holocaust reparations. All three bills work in concert to combat rising reports of antisemitism through these targeted cultural, economic, and educational channels.

Provenance

While other states are considering enacting similar legislation to increase Holocaust literacy in schools, New York stands apart in dictating these trailblazing requirements for museums to publicly acknowledge the devastating conditions under which they may have acquired certain works. The origin of a work of art is known as its provenance, and its applicability extends beyond Holocaust-era stolen works (you can access our blog post on the fight to prove provenance for Mexican antiquities here). Provenance is important not only to establish a chain of title when purchasing a work, but also to determine its cultural, political, and financial value.

Proving provenance is no small task, particularly when items have been stolen. This task is rendered even more difficult when the theft occurred during or shortly after the chaos of war. In the case of works stolen during the Holocaust, both these hurdles were present, with the added complications of global economic upheaval, unimaginable human suffering, an overwhelming refugee crisis, and the genocide of the class of people from whom the works were primarily stolen. The process of proving provenance for works stolen during WWII typically involves the heirs of deceased Jewish family members bringing claims to museums in hopes of establishing legitimate ownership of works held by a museum through whatever documents were salvaged after the war. This can include references in letters and diaries, family photographs, and bills of sale. The museum then has its own systems to determine the legitimacy of such claims. If provenance is not proven after the museum’s internal investigation, the museum is then able to claim that it “legally” retains the artwork.

Of course, this is devastating news to families seeking to reclaim an important piece of family heritage. If a museum denies heirs’ claims, they may proceed to file litigation. One high-profile example is Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Maria Altmann, titled Woman in Gold. Another is the ongoing Cassirer case, involving the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. However, these cases often take years – if not decades – to resolve, leaving the artwork in legal limbo until a final decision or settlement is made.

Of course, this is devastating news to families seeking to reclaim an important piece of family heritage. If a museum denies heirs’ claims, they may proceed to file litigation. One high-profile example is Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Maria Altmann, titled Woman in Gold. Another is the ongoing Cassirer case, involving the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. However, these cases often take years – if not decades – to resolve, leaving the artwork in legal limbo until a final decision or settlement is made.

It is important to keep in mind that Gov. Hochul’s new law does not specifically address the need to return works to individual families (restitution). However, it does bring to light the importance of acknowledging a work’s provenance as an important cultural indicator of the suffering of a class of people, even if it does not repair the harm done to individual families. Thus, the heirs or successors-in-interest of a dispossessed owner will need to rely on alternative avenues to recover their property.

Restitution

The effect of the public notice requirement speaks to justice outside the courts that can be accomplished through the voluntary restitution of stolen artwork. When restitution is carried out by leading art institutions as part of a larger “duty to remember,” it aids in cultivating peace and strengthening non-legal measures of restitution. Furthermore, it sets a positive example for other art world participants. While public art institutions have often not returned potentially looted art to the heirs of their original owners when proof of theft is not evident, many have expressed a desire to not retain stolen work. Even so, museums as a whole tend to be reluctant to part with prized pieces, particularly when the works claimed as stolen are the very ones that draw visitors to their galleries.

Case law

Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential settlement, and defended itself by claiming that the statute of limitations had run. In another case, the Metropolitan Museum of Art made the affirmative defense of laches, under the theory that claimants made an unreasonable delay in bringing suit against the museum for a valuable painting by Picasso.

Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential settlement, and defended itself by claiming that the statute of limitations had run. In another case, the Metropolitan Museum of Art made the affirmative defense of laches, under the theory that claimants made an unreasonable delay in bringing suit against the museum for a valuable painting by Picasso.

Even the most recent ruling in the Guelph Treasure litigation did not fare well for the claimant heirs. The Guelph Treasure litigation follows claims brought by the heirs to a priceless haul of German ecclesiastical relics, currently on display in the Bode Museum in Berlin. The heirs claim that the relics were sold under duress to the Nazi government in 1935 for less than their market value. The museum’s foundation argues that the sale was voluntary, and, further, was not made under the pressure of Nazi occupation in Germany.

Last month’s ruling by the District Court for the District of Columbia dismissed the case on jurisdictional grounds, stating that the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act (FSIA) blocked suit of Germany in U.S. court (this confirms the holding by the U.S. Supreme Court that remanded the matter to the district court). The claimants relied on an exception to the FSIA which prohibits expropriations that violate international law, arguing that dispossession in cases of genocide qualified for this rule. However, the court found that the claimants failed to prove that their ancestors were not German nationals at the time of the sale, meaning that only domestic law – not international law – was involved. As such, U.S. courts do not have subject matter jurisdiction over the matter, meaning that U.S. courts are unable to make determinations on German domestic law.

The district court’s decision does not eliminate the possibility of appeal or further pursuit of the Guelph Treasure through alternate measures in Europe. However, claimants often prefer to file disputes in the U.S. because American courts have historically been more lenient for Holocaust-related actions, particularly on statute of limitations grounds. In most European countries, causes of action for property stolen or lost during WWII have already expired. For example, Poland recently passed legislation that reduced the statute of limitations on all restitution cases to 30 years from the theft’s occurrence; this effectively bars all Holocaust restitution claims.

It is important to note that not all hope is lost. Some museums have, on their own initiative, refused to turn a blind eye to the problematic origins of some of their beloved works. The North Carolina Museum of Art, for example, returned a 16th-century painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder to an Austrian family after learning that the work was stolen by Nazi officials in 1940. And the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) recently returned View of Beverwijk by Salomon van Ruysdael to the descendants of a Jewish art collector and politican, from whom the work was stolen by Nazi forces.

In the case of the return of View of Beverwijk, the museum and the claimant family each had a role in making the restitution possible. First, the MFA received new provenance information regarding the work and updated its museum website. The family’s lawyer then used that new information to provide a missing link to prove their ancestor’s possession.

It was truly a moment of teamwork, and sets an example for other museums seeking to actively become part of the solution in remedying the trauma of the Holocaust. The MFA’s curator for provenance, Victoria Reed, stated (upon the return), “To be able to redress that loss, even in a tiny way, I think, is gratifying. And it certainly is part of what we should be doing as a museum.”

At the same time, voluntary returns of artwork by museums are few and far between, and the battle for individuals seeking to prove provenance remains a lengthy, cumbersome, expensive, and uphill battle. In light of these hurdles, requiring museums to publicly notify guests of the potentially tragic origins of works they have on display is a start. Doing so gives voice to the people who were silenced under the traumatic and systematic genocide of the Holocaust and lost their homes, families, and ties to their history and culture.

New York’s actions, in this sense, are an act of strength in the face of the general reluctance by museums to acknowledge that there are times in which the display of art may perpetuate war crimes. As Maya Angelou put it, “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived. But if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 1, 2022 |

A visit to the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto, MArTA) reminded me why I love museums so much. It is an inspiring place, a valuable educational resource, and an underappreciated repository for art and heritage.

Taranto, Italy

Greek ruins (Temple of Poseidon)

MArTA is located in Taranto, a city located along the inside of the “heel” of Italy in the region of Puglia. It was founded by Spartans in 706 BC, and it became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia (the Roman-given name for the coastal areas in the south of Italy — Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily — heavily populated by Greek settlers). Two centuries after its founding, it was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of around 300,000 people. Taranto (called Tarentum by the Ancient Romans) was subject to a series of wars, culminating in its fall to Rome in 272 BC. The city fell to Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but was recaptured (and subsequently plundered) by Rome in 209 BC. The following centuries marked the city’s decline.

Cathedral of San Cataldo

Taranto’s mix of architecture and rich cultural heritage is due, in part, to subsequent changes in leadership between the 6th and 10th centuries AD, during which time it was ruled by diverse groups: Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Arabs. Later, during the Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century AD, the city served as a French naval base, but it was ultimately returned to the Kingdom of Two Sicilies for a few decades before it officially became part of the Republic of Italy in 1861.

Due to its strategic location on the inlet of the Gulf of Taranto, the city has great naval importance. Taranto served the Italian navy during both World Wars. As a result, it was heavily bombed by British forces in 1940 (the bombing of Taranto and was even noted to have “set the stage for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor” the following year). The city was also briefly occupied by British forces during WWII.

Evidence of the city’s various iterations is evident throughout its streets with impressive cultural sites, including the Greek Temple of Poseidon, the Spanish Castello Aragonese (built in 1496 for the then-king of Naples, Ferdinand II of Aragon), and the 11th century Cathedral of San Cataldo (Taranto Cathedral), where the remains of the city’s patron saint, Saint Catald, lie (he is believed to have protected the city against the bubonic plague). More recent architectural gems include Palazzo Galeota and Palazzo Brasini.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MArTA)

Like the city where it is located, MArTA is a rich institution full of incredible treasures. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit MArTA in person. Sadly, the museum, and the city itself, tend to fall under the radar of tourists. It is unfortunate that this site escapes attention, because both Taranto and its vaunted museum are incredible.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

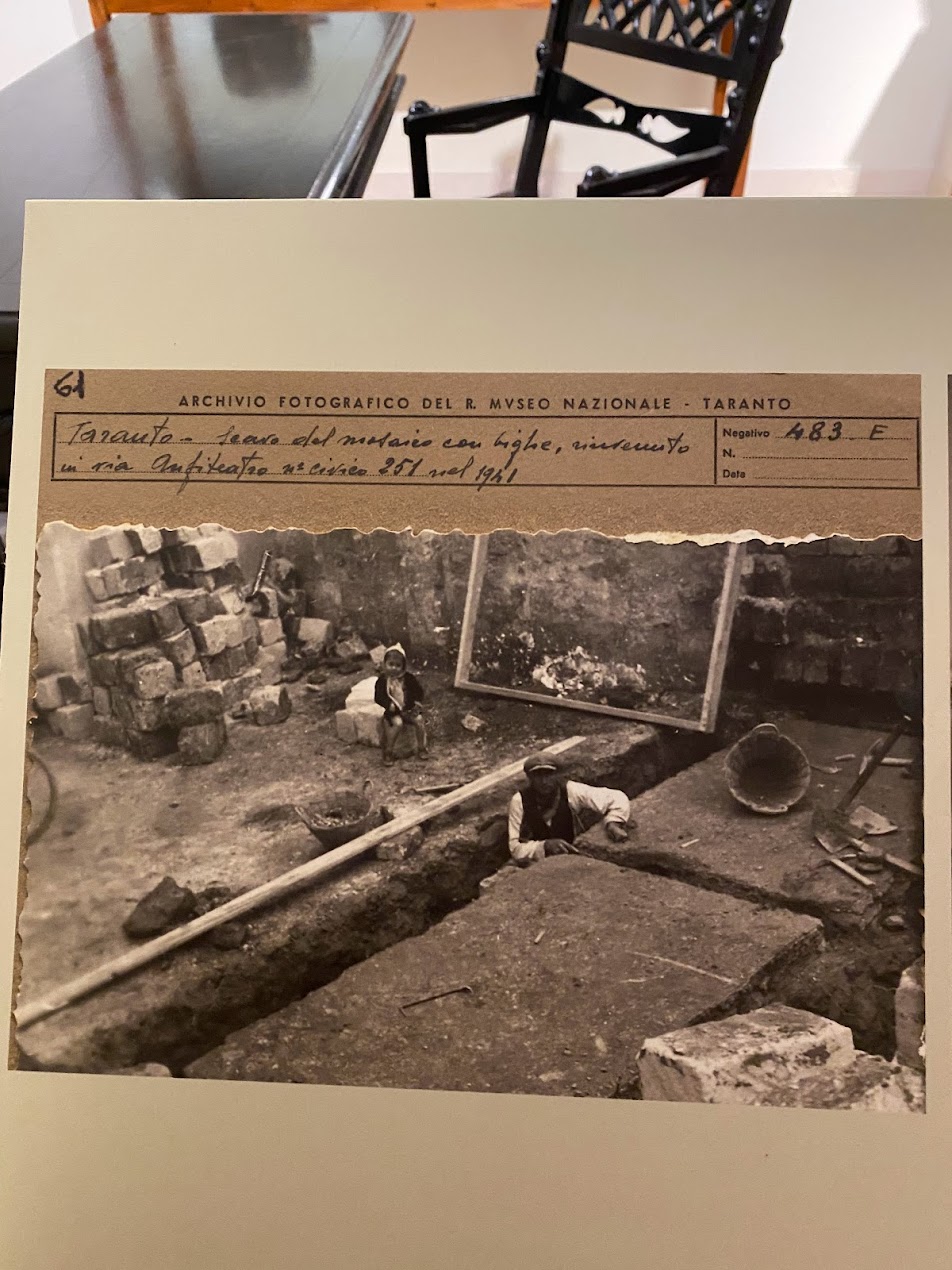

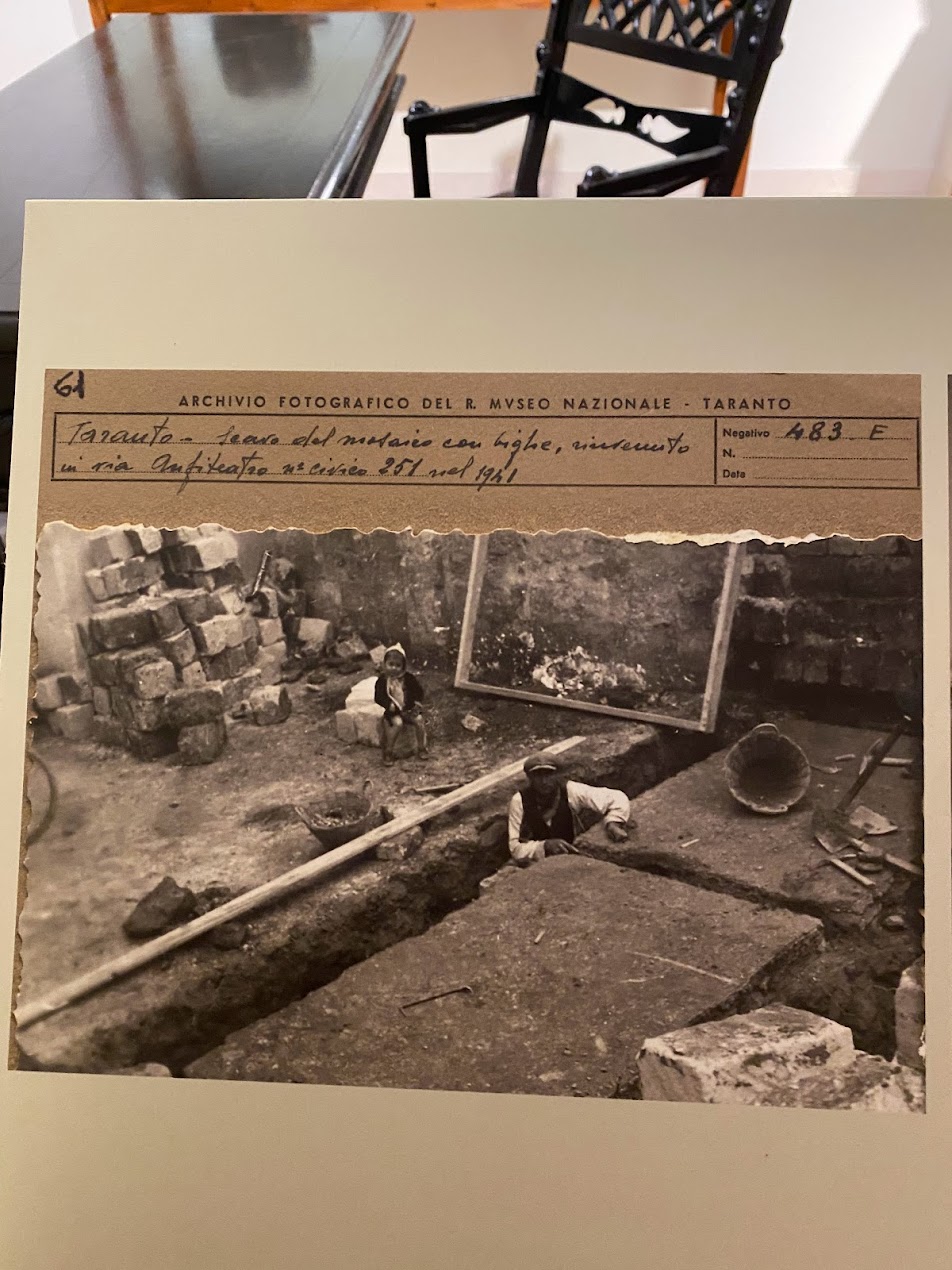

Amongst other treasures in MArTA are beautifully preserved mosaics, ornate golden jewelry, and ancient gold-covered snake skins. Another museum highlight are the informative displays positioning objects in creative contexts. For example, some objects are displayed along with photographic evidence and documentation about their excavation.

Tomb of the Athlete

The museum presents objects in beautiful vitrines. Some of the highlights on the first floor include thematic displays, such as a wall depicting Medusa’s face on antefixes found in Taranto. The curation includes information about the figure of Medusa in mythology and details on how her portrayal evolved over time. Another engaging display involves #italianmuseums4olympics, the Ministry of Culture’s campaign to support Italian sport and culture during the Olympic games. That particular display includes the sarcophagus of an athlete from Taranto, complete with amphorae found in his tomb that include images of athletic competitions, celebrating Italy’s long tradition of participating in the Olympics since antiquity.

An Apulian krater by the Darius painter returned from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2009

Looting of Objects on Display

As visitors enter the next floor of the museum’s route, they are confronted with a large restituted antiquity. A large Apulian krater by the Darius painter was returned to Italy in 2009 from the Cleveland Museum of Art after it was recovered by the Carabinieri’s TPC (the nation’s famed “Art Crime Squad”). The work was among fourteen artifacts returned from the Ohio museum after a two-year negotiation resulting from the investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici and Gianfranco Becchina, two well-known dealers of looted materials who sold antiquities at auction and through dealers to supply coveted objects to collectors and museums around the world.

Loutrophoros restituted by the J. Paul Getty Villa in Malibu in California

MArTA also acknowledges some of the people responsible for the development of its exquisite collection, including past directors and donors. The displays note that the illicit or unknown sale of antiquities has led to the loss of knowledge about their historical and cultural value (when artifacts are illicitly excavated and divorced from their contexts, valuable information is lost in the process). However, the development of patrimony laws has allowed the Italian government to control more of the archaeological discoveries taking place, and other legislation has also encouraged collectors to donate their property to the museum and Italian State. The display also notes the important work by law enforcement and its success in having works repatriated to Italy, as well as its success in confiscating looted artifacts from private owners and collectors during the 20th and 21st centuries in Italy. Part of this display features works returned from major museums abroad, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum in Malibu, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Labels and Information

The labels and information offered to visitors at the museum is exceptional, providing valuable information about the historic significance of items on display. Clearly, the museum places great importance on provenance, providing detailed information on where objects were excavated (this information includes exact find spots, with cross streets included for some of the objects), how they entered the museum’s collection, and ways in which the museum has evolved over the decades. Additional information is available to visitors about looting and criminal acts related to the objects, providing useful context.

Copy of the Goddess on Her Throne (the original is in Berlin)

One of the first objects to greet visitors upon their entry is a copy of a goddess on her throne. The original 5th century BC statue is “considered one of the greatest artworks from Magna Graecia.” It was found in 1912 in Taranto, but illegally exported out of Italy. It was then put on the Swiss art market, and finally purchased by the German government. It is currently on display at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Information like this is valuable, because it forces visitors to confront the political, societal, and cultural pressures facing museums, as well as the challenges and realities of the art and antiquities markets. It also provides a practical example of how works can wind up in international museums divorced from their original historical and cultural context.

As the museum’s website states, “The Museum also lends artefacts to other museums to allow global citizens to enjoy. We are aimed at providing first-hand information to all of our visitors so that they understand Europe’s prehistoric period.”

Castello Aragonese

A visit to this museum, and the gorgeous city of Taranto, with its sweeping coastal views, its rich cultural history, and its stunning architectural masterpieces, is essential for anyone visiting Puglia.

Copyrights in all photographs in this post belong to Leila Amineddoleh

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Objects from the museum’s early collection

Documentation of excavations

Vitrine (provenance information for each object is provided in a side panel)

Provenance on view

Beautiful entryways on each floor

Context with a photograph

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 2, 2022 |

The Marble Bust found in Texas that will be returned to Germany

Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to announce its role in a recent antiquities matter, whereby a Roman marble bust looted during WWII will be restituted to the Bavarian government in Germany. Below, we share details about the bust’s provenance, examples of other cultural objects looted during World War II, the vital work by experts in establishing provenance, and our role in this important cultural return.

I. HISTORY OF THEFT DURING WWII

Much of the literature about WWII-era looted art focuses on thefts perpetrated by the Nazi Party. The Nazis pillaged on a continental scale – appropriating about 20% of all art in Europe at the time. They were notorious for confiscating artworks they deemed “degenerate,” although other works of art were also swept up in their violent mass seizures. One example is the extensive Czartoryski family collection from Poland, which included Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci (later recovered) and a portrait of a young man by Raphael (still missing). After the occupation of Paris in 1940, over 20,000 looted works were taken to the Jeu de Paume gallery, and were kept in a place known as “The Room of the Martyrs.” While Hitler and high-ranking officials had first pick of the loot, German officers could later select masterpieces of their choice. The remainder were slated for destruction, but some evaded this fate thanks to the efforts of art historians and the famed Monuments Men (this title is a misnomer, as this group of British and American members included women).

Looting is often a crime of opportunity, and soldiers on all sides of a conflict may take advantage of the situation by partaking in the appropriation of stolen valuables. Allied soldiers during WWII were no exception. Some of the goods pilfered by Allied troops, like cigarettes and household goods, are relatively inexpensive or nearly worthless by today’s standards. But others – including paintings, rare coins, historic photos, musical instruments, and antiquities – possess great artistic and cultural value. Those valuables continue to be found to this day, sometimes in surprising locations. Some have been returned to the heirs of the original owners while others are involved in ongoing litigation.

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer

In one instance, a member of the U.S. Army stole a collection of medieval religious objects that had been hidden in a cave for safekeeping during the war. The soldier mailed these priceless artifacts home to his family in Texas. These items, known as the Quedlinburg Treasure, included a jeweled 9th-century manuscript written entirely in gold (the Samuhel Gospel). Decades later, the soldier’s heirs reached an agreement with Germany and returned the items in exchange for $2.75 million. Another case involved a pair of portraits by Albrecht Dürer stolen from a museum in East Germany during the war. These were taken by an American serviceman and later bought by a New York collector, Edward Elicofon, for $450. Although Elicofon was purportedly unaware of the paintings’ provenance, a friend recognized the works from a book on art stolen during WWII. After the museum filed a lawsuit in New York, the court compelled Elicofon to transfer ownership and possession of the works back to Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar (Weimar Art Collection).

Perhaps the best-known case involves Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as the Woman in Gold. This gilded painting was forcibly seized by the Nazis after the owners, a Jewish family, were forced to flee Austria in fear of their lives. The portrait is called “the Mona Lisa of Austria.” Along with other works from the Bloch-Bauer’s collection, the portrait wound up in the Austrian State Gallery, but the heirs to the estate fought to recover their family’s lost property. Eventually, after litigation in the U.S. and arbitration in Austria, the Bloch-Bauer heirs succeeded. The dramatic tale became the subject of a film starring Helen Mirren as the main claimant, Maria Altmann, and the painting was later sold in 2006 for $135 million – a record price at the time.

II. AN ART LOVER DISCOVERS THE MARBLE BUST

Not all art and heritage restitutions involve contentious battles. The most recent example of a voluntary return of valuable WWII-looted art can be found in the just-announced agreement between Germany and our client, Laura Young.

The Marble Bust safely strapped in Ms. Young’s car with a seatbelt

Ms. Young happened upon the Marble Bust in the unlikeliest of places: a goodwill thrift shop near her home in Austin, Texas. She purchased the artifact and immediately realized it was more than it appeared to be. The 52-pound Marble Bust, standing at 19 inches tall, was in fact an extremely valuable antiquity. After she drove the Marble Bust home (responsibly strapped into her car with a seatbelt), Ms. Young began digging into its past and discovered the remarkable nature of her find.

Ms. Young later confirmed that, unbeknownst to the goodwill thrift shop owner, the Marble Bust depicts famed Roman commander Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, known simply as Drusus Germanicus or Drusus the Elder. She went on to discover that the Marble Bust has a significant provenance, including links to royalty.

The Marble Bust’s Provenance

- A Roman Marble Portrait Head of Drusus Germanicus (early 1st century AD)

- Acquired by King Ludwig I of Bavaria (before 1833)

- Exhibited in the Pompejanum, Aschaffenburg, Germany (presumably by 1848)

- Stolen during WWII (1944 or 1945)

- Consigned to a goodwill shop in Austin, Texas (Unknown date)

- Purchased by Laura Young (2018)

- Title transferred to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes) (2021)

- Loan to the San Antonio Museum of Art (2022-2023)

A Bit of Roman History

To truly appreciate the richness of the Marble Bust’s provenance, a bit of history is required.

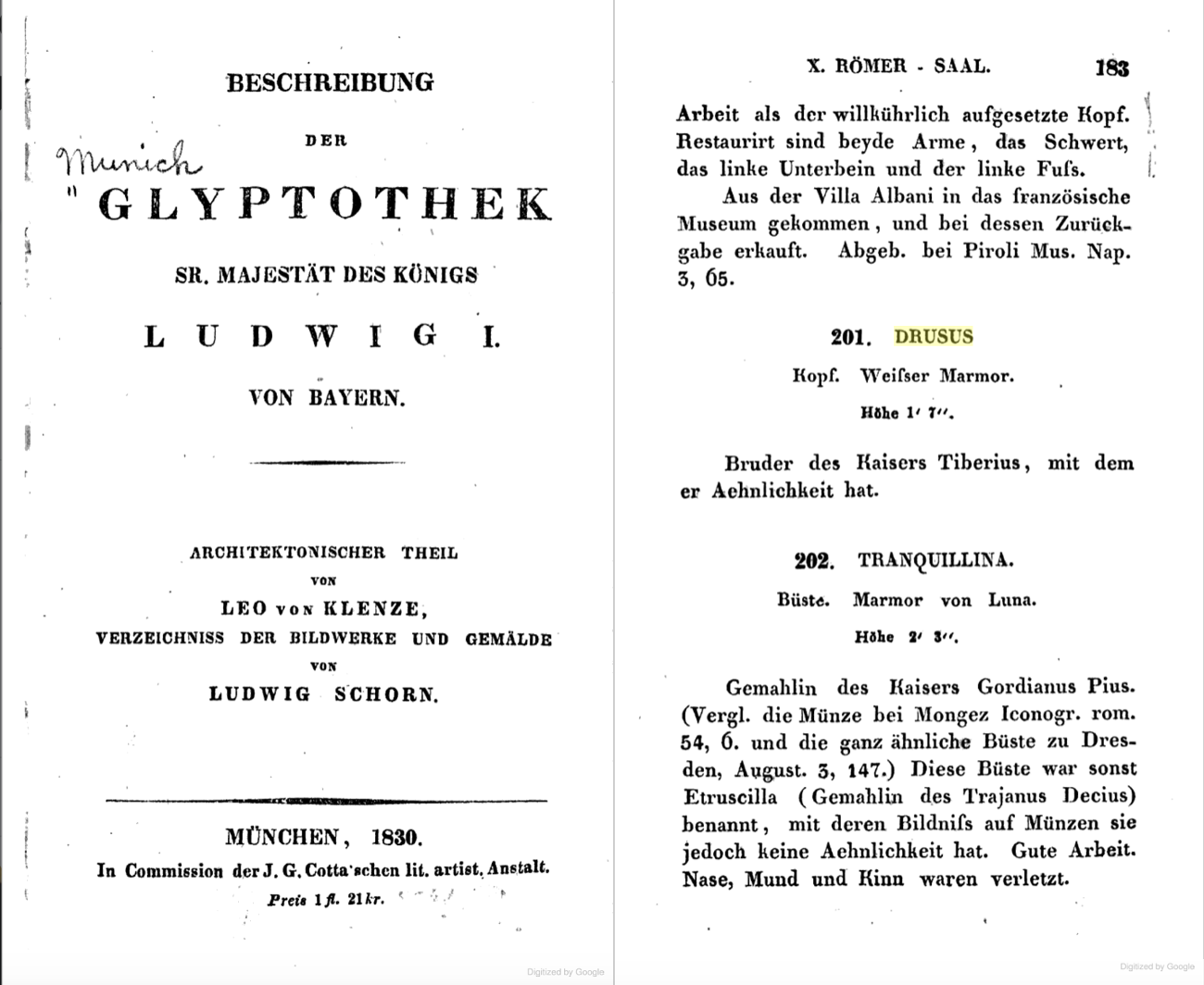

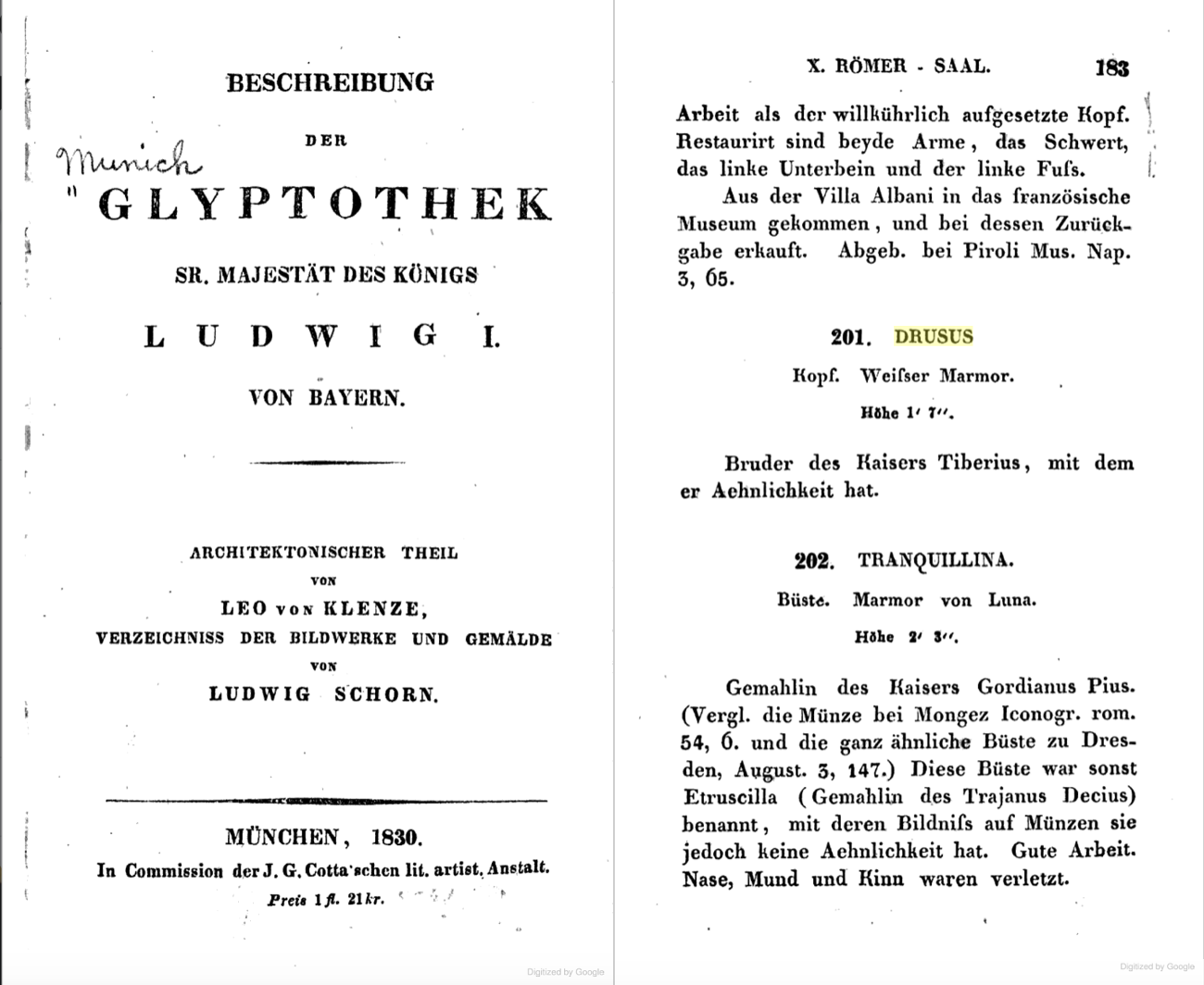

Left, cover of 1833 catalog of King Ludwig I’s antiquities collection , right, description of Drusus (the Marble Head) listed in the catalog

Image from google books digitized version of the catalog

Born on January 14, 38 B.C. to Livia Drusilla and Tiberius Claudius Nero, Drusus Germanicus was the legal stepson of Livia’s second husband, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus and great-nephew of Julius Caesar). Drusus was born shortly after his mother’s divorce, and his mother immediately married Octavian, who historians suspect was Drusus’ true father. Drusus Germanicus eventually became the commander of the Roman forces occupying the German territory between the Rhine and Elbe Rivers. In 9 B.C., Drusus reached the Elbe River, but he was thrown from his horse and died 30 days later from the injuries he sustained. For his conquest of Germania, he received the posthumous honorific title “Germanicus.” The Marble Bust of Drusus Germanicus traveled to Germany nearly two millennia later after its acquisition by the King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, at some point prior to 1833.

Although Drusus was lesser known than some other members of his family, portrait heads of this figure are rare (perhaps due to Drusus’ early death) and highly prized.

Ludwig I and the Pompejanum

After its acquisition by Ludwig I, the Marble Bust was transferred to a most fitting location – the Pompejanum. The Pompejanum (or Pompeiianum) is a replica of a Roman townhouse in Pompeii. Overlooking the Main River in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg, the museum was already a popular tourist destination in the 19th century. The Pompejanum was commissioned by Ludwig I, who was inspired, like many cultural enthusiasts, by the excavations at Pompeii.

Ludwig I was both an art lover and a great patron of the arts. During his reign from 1825 through 1848, he commissioned major museums and art projects throughout Bavaria and the rest of Germany in a bid to elevate Munich to the status of rival European art capitals, like Rome and Paris.

His passion for art was first awakened on a trip to Italy from 1804 to 1805. After that trip, the future king became a voracious collector. Much like today’s collectors, he sent agents across Europe to acquire masterpieces. (One of his art dealers, Johann Martin von Wagner, was noted for his unerring eye, scholarly talent, and great commercial aptitude.) With an unlimited amount of money to draw on from his royal coffers, Ludwig I scooped up many highly sought-after pieces. To display his massive collection, Ludwig I commissioned the construction of a number of major museums. One of his first projects was the Glyptothek, which was used to house ancient sculptures. Another, the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities), was designed in 1848. The works from that institution formed part of the extensive collection of the Bavarian Royal Family.

Ludwig I’s taste in art also ventured beyond the ancient world. In 1836, he created the Alte Pinakothek, the largest museum in the world at the time of its inauguration. Ahead of his time, Ludwig I also established one of the first contemporary art museums in the world–which was unfortunately destroyed by bombing during WWII.

Ludwig I had a deep appreciation for ancient masterpieces and structures evoking the classical era. Projects inspired by this passion include the Propylaea, a monumental city gate constructed as a copy of the Athenian Acropolis and ultimately dedicated as a memorial for Ludwig I’s son Otto, who ascended to the throne of Greece in 1832. It was financed by Ludwig I’s private resources after his abdication, and serves as a symbol of friendship between Greece and Bavaria. While he was still a young crown prince, Ludwig I conceived the project of Walhalla, a temple erected to honor famous Germans. This hall of fame honors nearly 200 laudable people spanning 2,000 years of German history, including both male and female politicians, sovereigns, scientists, and artists, from Albrecht Dürer to Sophie Scholl. Although it is named after the Norse mythological heaven for warriors, the temple was built in the Greek Revival Style and modeled after the Parthenon. The temple continues to be used today, and 19 busts, including one of Albert Einstein, have been added to the collection since WWII.

Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Germany, as restored today

© Carole Raddato (owner of Following Hadrian)

Ludwig I also aspired to bring a bit of ancient Rome to Bavaria. As such, he commissioned the Pompejanum, mentioned above, which was constructed between 1840-1848. Designed by architect Friedrich von Gärtner, it was loosely modeled on the House of the Diosuri (Casa dei Dioscuri) in Pompeii. The villa was never intended to be used as a residence; rather, it has always served as a museum. Located near Schloss Johannisburg (one of Ludwig I’s residences), the king could admire it from his window and make frequent visits. Completed with a Mediterranean-style garden and filled with reproductions of mosaics, architectural forms, and artifacts, the king could escape to Italy with just a short trip to the Pompejanum.

Visitors came to the Pompejanum because it was, and perhaps still is, the most accurate reconstruction of a Roman villa in the world. The ground floor features an entrance hall, the guest room, the kitchen, the dining room, and atrium, all organized around two courtyards. The interiors were painted in the Pompeiian fresco style, and the floors feature copies or adaptations of ancient works and Roman mosaics. The collection included Roman marble sculptures, bronze statuettes and glasses, and household items, as well as two god’s thrones made of marble.

Destruction of the Pompejanum

The Pompejanum destroyed after WWII bombings

Sadly, as often happens during conflict, the damage to the museum’s physical structure led to the loss of its collection. The Pompejanum and the surrounding areas were heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1944 and 1945. Some of the museum’s objects survived bombing only to be looted. But nothing looted from the museum was ever sold by the museum or German government, and thus title to any looted property remained with the Bavarian State. Under U.S. common law principles, valid title to artwork cannot be transferred through looting. There must be a legitimate transaction for title to vest legally in a subsequent purchaser. This means that the Bavarian State continues to maintain a legal claim of ownership over objects that were taken from the Pompejanum.

The Pompejanum Today

The Pompejanum was eventually restored during several phases, the first beginning in 1960. The restoration was completed in 1994, and the villa reopened to visitors that year as the museum of the Bavarian Palace Department and the State Antiquities Collections. Today, it is open to visitors from the spring through the fall.

III. AN ART EXPERT ILLUMINATES THE MARBLE BUST’S PROVENANCE

Establishing the provenance of artwork and antiquities is essential, particularly for objects displaced during times of conflict. It is important not to underestimate the role of art experts in determining provenance, as well as the return and restitution of looted objects. Due to their specialized knowledge and access to resources that are not necessarily available to the public, art experts play a crucial role in establishing the provenance of works and alerting owners to potential red flags. It is always important for purchasers of artwork with unclear provenance or gaps in the chain of ownership to consult experts and ensure that title has been properly transferred.

This pre-war-photo shows the Bust, together with another (today in the Antikensammlungen), standing in the Atrium at the entrance of the Tablinum.

To research her new-found treasure, Ms. Young contacted Sotheby’s. The auction house’s consultant researcher in Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, Jörg Deterling, identified the subject of the Marble Bust as Drusus Germanicus and alerted Ms. Young that the work had gone missing from the Pompejanum decades ago. Before being looted, the Marble Bust had been displayed in the Atrium, at the entrance of the Tablinum that led to the Pompejanum. Although the exact path of the Marble Bust from Bavaria to Texas is unknown, it is safe to assume that it was looted either by an American serviceman who brought it back to the U.S. or by someone who eventually sold it to an American, likely during WWII or immediately after the end of the conflict.

According to Sotheby’s, Mr. Deterling has been “responsible for many returns, restitutions, and repatriations over the years, but his name has never appeared anywhere in connection with them.” Here, he once again played an instrumental role in the return of a valuable artwork by informing Ms. Young about the historical significance and provenance of her find.

IV. AMINEDDOLEH & ASSOCIATES HELPS MS. YOUNG RESTITUTE THE MARBLE BUST TO GERMANY

Drusus Germanicus on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art

After being informed of the Marble Bust’s provenance, Ms. Young worked with Amineddoleh & Associates to voluntarily transfer title to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes), a government agency in Bavaria, Germany. As part of the restitution agreement, the Bavarian agency committed to loaning the Marble Bust to the San Antonio Museum of Art where it is expected to remain on view until its scheduled return to Germany in 2023.

Rather than sell the Roman bust on the antiquities market, where she could have made hundreds of thousands of dollars, our client instead chose to act ethically and return the bust to its rightful home. We worked with Ms. Young to communicate with German authorities, negotiate the transfer of title, ensure proper acknowledgement of Ms. Young’s actions, and request the work’s temporary display in Texas where its story and our client’s role could be further relayed. The Marble Bust’s journey is an extremely important story to tell. It reflects our passion for the past and collecting, the value of museums in providing access to heritage and knowledge, the unfortunate displacement and destruction of national and cultural heritage during conflict, and the hope that people and institutions will choose to act ethically and protect our shared heritage.

In fact, earlier this week the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced the return of a looted marble sculpture to Italy. As in the case with Drusus Germanicus, the object was likely stolen during WWII. The MFA had purchased the antiquity from a Swiss dealer in 1961 for $750. Other records of its whereabouts prior to the purchase are lost, but the dealer had represented that the object originated from Rome. Unfortunately, the MFA’s sculpture had suffered significant damage, such as the loss of facial features, including its nose, mouth and lower left cheek. The Boston museum worked with the Italian Ministry of Culture to effectuate the return of the looted antiquity.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to represent clients who value cultural heritage and consult us in matters involving provenance, authentication, ownership, and restitution. In doing so, they help ensure that cultural heritage is protected and safeguarded for current and future generations while being shared with as many people as possible. Thank you to The Art Newspaper for sharing details about this story HERE.

When does the law protect fashion brands? And what is the cost to other artists? Our firm answered these questions in this posts inspired by the Fall 2022 Fashion Weeks taking place around the world. Prominent fashion designers have been known to incorporate logos of other brands into their designs, often as a part of social commentary. Even where artistry is the intent behind the repurposed logo, these designers face financially devastating intellectual property claims from major the brands and companies who own the rights to the logo. Our firm considered how to balance protecting consumers from consumer confusion with giving designers the artistic liberty to create fashion that sparks social commentary. Read more on our website.

When does the law protect fashion brands? And what is the cost to other artists? Our firm answered these questions in this posts inspired by the Fall 2022 Fashion Weeks taking place around the world. Prominent fashion designers have been known to incorporate logos of other brands into their designs, often as a part of social commentary. Even where artistry is the intent behind the repurposed logo, these designers face financially devastating intellectual property claims from major the brands and companies who own the rights to the logo. Our firm considered how to balance protecting consumers from consumer confusion with giving designers the artistic liberty to create fashion that sparks social commentary. Read more on our website.

Auction Sales

Auction Sales Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential

Decades of case law in the U.S. indicate the difficulties facing claimants. Recent cases against New York museums resulted in wins for the institutions, yet not due to the merits of each respective case. Rather, the Museum of Modern Art squeaked out wins through a confidential

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4