by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Nov 20, 2020 |

Golden Coffin of Nedjemankh– looted from Egypt and sold with false provenance

The Victoria & Albert Museum in London is currently closed, but it continues to create and distribute valuable content examining issues related to art and heritage looting. Through Culture in Crisis, a program bringing together individuals and organizations with a shared interest in protecting cultural heritage, the museum is actively engaging with heritage professionals to provide insights into the dangers facing our shared history. One tool for raising awareness of these issues is the Culture in Crisis Podcast.

Season Two, Fighting the Illicit Trade, is comprised of interviews with international experts working to prevent the illegal trade of cultural heritage– each person fighting a battle to rescue cultural heritage at a different stage of its underground journey. The series examines the actions taken at the object’s source, through transit, and upon arrival at its destination. As stated by Culture in Crisis, “The theft and sale of cultural property robs communities of their past, present and future. It lines the pockets of international criminal networks and has been shown to directly finance terrorism. Through this series we hope to highlight valuable initiatives working to prevent the illicit trade and gather recommendations on how to build on these efforts in the future.”

Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, is interviewed in Episode 7, “You’ve Gotta Have (Good) Faith.” She offers a legal perspective about heritage looting, discussing legal cases, provenance (including false provenances), good faith purchases, and the due diligence involved in purchasing antiquities. Read more about the series and listen to the informative interviews here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 31, 2020 |

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

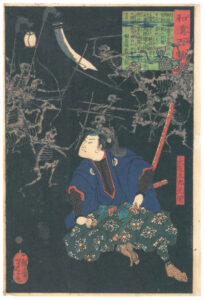

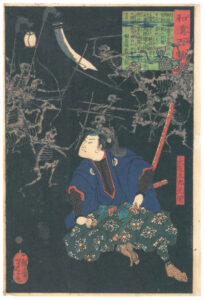

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, born in 1839 in Japan, is known as one of the last great masters of the Japanese woodblock print. One of his masterpieces a series of works, 100 Ghost Stories from China and Japan. The series, created in 1865, includes images of skeletons, ghosts, and other supernatural creatures. One well-known print is Japanese samurai warrior, Oya Taro Mitsukuni watching a battle scene between armies of skeletons.

Leizhen (Raishin), MFA Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA) owns Leizhen (Raishin), from the series. The work, signed by Ikkaisai Yoshitoshi ga, was purchased by William Sturgis Bigelow in 1911 and then gifted to the MFA. Bigelow was a prominent American collector of Japanese art. He lived in Japan for seven years. The Japanese government authorized him and two other Americans to explore parts of Japan that had been closed to outside viewers for centuries. During his time there, he acquired valuable art, including the mandala from the Hokke-do of Tōdai-ji, one of the oldest Japanese paintings to ever leave Japan. Bigelow donated approximately 75,000 objects of Japanese art to Boston MFA. Due to the huge donation, the still has the largest collection of Japanese art anywhere outside Japan.

Perhaps even more haunting is a series of fourteen works, the Pinturas Negras (Black Paintings), created between 1819 and 1823 by Spanish painter Francisco Goya. The works depict dark themes that reflected Goya’s own fears and his bleak view of humanity, in part due to the fact that the Spanish master was going deaf. At the age of 72, Goya moved into a home outside of Madrid known as La Quinta del Sordo (the Deaf Man’s Villa). The previous owner was deaf, and Goya was nearly deaf by the time he moved into the home. During this despairing time, Goya painted a series of unsettling works, such as murals on the walls of his house. They were eventually transferred to canvas.

Witches’ Sabbath, El Prado

One of the most macabre is the work now known (Goya did not title the murals) as the Witches’ Sabbath (El Aquelarre) or The Great He-Goat (El Gran Cabrón). Like most of the other works in the series, it was painted with dark and earth-toned colors. The painting depicts a witches Sabbath attended by the Devil in the form of a goat. The He-Goat appears as a silhouette painted entirely in black, except for one eye. Facing the demonic creature is a coven of witches and warlocks, portrayed with hideous features. The series of works was acquired by the Baron Emile d’Erlanger when he purchased the “Quinta” in 1873. He had the murals transferred to canvas, but they suffered great damage. The Baron ultimately donated the works to the government of Spain, which in turn moved them to the Prado, a national museum located in Madrid, to be publicly viewed.

The portrayal of devils and demons in works of art dates back millennia. Featured in The Exorcist, Pazuzu is the main antagonist who is exorcized from its victim. But the demon was not just the creation of the author of the The Exorcist, William Peter Blatty. The demon derives from Assyrian and Babylonian mythology, where it was considered the king of the demons of the wind, and the son of the god Hanbi.

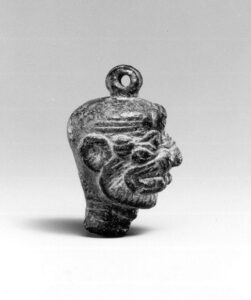

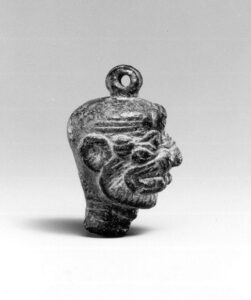

Pendant of Pazuzu, Metropolitan Museum of Art

On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) is a small pendant of the demon, dating from the 8th to 7th century BC. The pendant has bulging eyes, bulbous forehead protrusions, and short beard that rings the snarling open mouth, atop an incongruously thin neck. These are his unmistakable features.

According to the Met, Pazuzu appears on many plaques and amulets, sometimes as a figure with wings and a scorpion tail. The earliest image of Pazuzu dates to the late 8th century B.C., relatively late in the history of demonic imagery in Mesopotamia. The museum states that this was a period when the Assyrian royal administration was intensely focused on collecting magical knowledge and studying the supernatural world, and priests and exorcists were actively engaged in codifying these systems of knowledge. As a result, a rich variety of magical images and texts from Assyria in this period have survived. The pendant was sold at Hôtel Drouot, Paris, on May 19-20, 1987, and eventually it was acquired by the museum in 1993, purchased at Sotheby’s New York, on June 12, 1993.

In addition to the demonic pendant, the Met owns other spooky art, including this photograph of a ghostly apparition.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 29, 2020 |

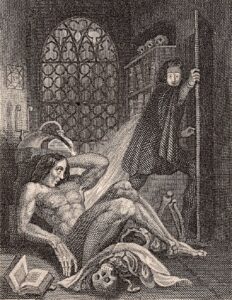

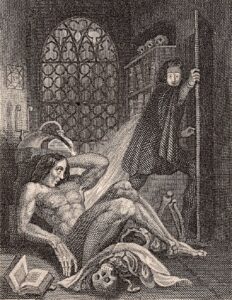

Illustration from the frontispiece of the revised edition of Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London 1831.

Some of Hollywood’s most famous “monsters,” jumped off the pages of Gothic novels to the excitement and fear of spellbound readers. One of the most famous is the monster from Frankenstein. At the young age of just 18, Mary Shelley created a tale that would fill readers with dread, as well as empathy. Frankenstein, the Modern Prometheus, was a being imbued with humanity seeking love and acceptance. The teenage Mary Shelley created her tale during a ghost-story competition one stormy evening in the summer of 1816 while on holiday in Switzerland with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John Polidori. During the course of her edits, the “monster” evolved from a “being” to a more human creature, and the book was first published in 1818.

As Mary Shelley’s horror story shaped Gothic literature, her copious notes and edits have been studied by historians, academics, and fans of the novel. The pages are now available online to viewers around the world on the Shelley–Godwin Archive. The original transcript is currently in the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford as part of the Abinger Collection. The collection was given to the university, in batches between 1974 and 1993, by James Scarlett, 8th Lord Abinger.

The Abinger papers are the residue of the collection of the Shelley family’s papers from Boscombe Manor (near Bournemouth, Dorset), the home of Sir Percy Florence Shelley, 3rd Baronet of Castle Goring (1819-1889), and his wife Jane, Lady Shelley (1820-1899). Sir Percy had inherited the family archive from his mother, Mary Shelley. She maintained papers from her parents, her husband, and from her own writing.

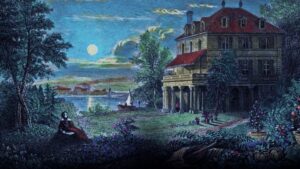

Villa Diodati, near Geneva, where literary character Frankenstein was created in 1816. (Credit: DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Since Mary Shelley had a close relationship with her daughter-in-law, it was Lady Shelley (Jane Shalley) who cared for and acquired additional items for the family archive. After her husband’s death, Lady Shelley endowed the Shelley Memorial at University College (1893) and she gave selected notebooks, letters and relics to the Bodleian Library (1893 and 1894). She bequeathed most of Mary Shelley’s other notebooks, relics, and papers to her husband’s cousin and the heir to his baronetcy, John Courtown Edward Shelley, later known Sir John Shelley-Rolls (1871-1951). Sir John gave the notebooks to the Bodleian Library in 1946.

Jane Shelley bequeathed her houses with their residual contents to her two eldest grandsons, Shelley and Robert Scarlett. Eventually, Shelley and Robert became respectively the 5th and 6th Barons Abinger, both childless. The majority of the papers were passed to their brother Hugh, the 7th Baron Abinger. When Hugh’s son James became the 8th Baron Abinger in 1943, he took a serious interest in the family papers. In the early 1970s, Lord Abinger gave permission for the Shelleys’ joint journal to be prepared for publication by Oxford University Press, and deposited the original journals at the Bodleian for the editors’ use. This led to Lord Abinger’s decision to provide the entire collection on long-term loan at the Bodleian in nine batches between 1974-1993.

Lord Abinger’s son James succeeded him in 2002. He put the papers on the market, but gave the right of first refusal to the Bodleian Library. The library launched a campaign to raise the funds. This mission was accomplished in 2004, when the Abinger collection was bought outright by the Bodleian Library with donations from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation, and many other institutional and individual donors. Cataloguing of the papers was completed in 2010 with the aid of a grant from the John R. Murray Charitable Trust.

The information presented in this post can be found HERE.

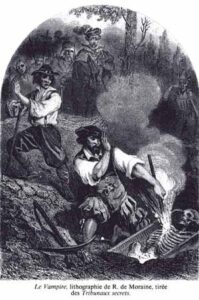

Vlad Tepes dining while surrounded by the impaled bodies of his enemies; hence, the name “Vlad the Impaler.”

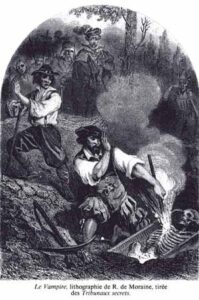

Another horror novel that has haunted generations of readers is Dracula. Inspired by tales of ruthless acts of violence and revenge exacted upon the Ottoman enemies of Vlad III (Vlad the Impaler, Vlad Tepes, or Vlad Dracula), Bram Stoker portrayed the Romanian ruler as a vampire and incorporated Romanian folklore about vampires in his novel. Written between 1890 and 1897, it is Stoker’s best known work. Count Dracula is one of the most filmed characters, and the tale has inspired countless other works, films, theatrical productions, and cultural references.

Nevertheless, the original manuscript had disappeared for decades. In a story worthy of the famous Gothic novel, the manuscript was lost and eventually found. In the 1980s, the heirs of Thomas Corwin Donaldson (a friend of both Bram Stoker and Walt Whitman) unearthed the manuscript of Dracula in a barn in Pennsylvania. Donaldson’s heirs sold the papers and manuscript through Peter Howard of Serendipity Books in Berkeley, California. Howard offered it to another book dealer and collector, John McLaughlin (owner of The Book Sail in Orange County, California). McLaughlin’s 1984 catalog lists the manuscript. Due to financial concerns, in 2002, McLaughlin consigned the manuscript to auction at Christie’s in New York.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 9, 2020 |

Photo session for Maenad statue at via della Lungara in Rome, ©FondazioneTorlonia, Ph. Lorenzo de Masi.

Not only do objects have provenances, but so do collections. One of the world’s finest privately held collections will be shared with the public starting later this month. The collection is housed in Rome, and while it is difficult to travel during this time, we are pleased to share a blog post about the upcoming exhibition in Italy. The following blog post was written by colleagues in Italy at Milestone Rome. Founded by two Roman locals, Milestone Rome is an independent cultural project aimed at spreading appreciation for the Eternal City and disseminating knowledge about its rich cultural heritage through art historical information enhanced by digital technologies. The group promotes academic-quality cultural content, and its website and app are also wonderful resources for travelers who visit Rome. Amineddoleh & Associates is pleased to share Milestone Rome’s post with our readers. Read more about the group on its great website.

The Storied Torlonia Collection of Ancient Marbles is Finally on View in Rome

Group of restored statue at via della Lungara in Rome, ©FondazioneTorlonia, Ph. Lorenzo de Masi.

Almost 100 exquisite marble sculptures belonging to the renowned Torlonia Collection will be shown to the public on the occasion of the long-awaited exhibition I marmi Torlonia: Collezionare capolavori (“The Torlonia Marbles: Collecting Masterpieces”). After a turbulent year of delayed cultural events, the highly anticipated exhibition will be on view at the Capitoline Museums in Rome from October 14, 2020 until June 29, 2021. This will be its first stop on an unprecedented world tour. The exhibition is curated by two archaeologists and academics from the Accademia dei Lincei, famed Italian art historian Salvatore Settis (who was entrusted with the scientific project) together with art historian and professor Carlo Gasparri. The event is made possible thanks to a historic agreement between the public Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism and the private Fondazione Torlonia.

The successful negotiation, reached in 2016, comes after many years of a complex disputes between the noble Torlonia family and the Italian State. For this reason, the collection was hidden to the public for over 40 years. As a result, the exhibition in Rome will surely be one of the most important art events of the year or even of the decade.

The Troubled History of the Torlonia Collection

The Torlonia Family is a noble family from Rome that acquired a massive fortune in the 18th and 19th centuries overseeing finances for the Vatican. With its wealth, the family became major collectors of art. In fact, the complete Torlonia Collection is much larger than the selection of 96 pieces to be displayed as part of the exhibition. The collection includes 620 artworks that were catalogued in 1881 by Pietro Ercole Visconti as the result of a long series of acquisitions and excavations. The collection grew as the family purchased entire art collections that belonged to princely families in decline, such as the Giustiniani Collection. The Torlonia Collection was housed in a number of residences owned by the noble family, adding to the family’s prestige and title.

Giuseppe Primoli, A visit to the Torlonia Museum, 1898 ca., image via Wikimedia Commons.

The history of the Torlonia Collection took a turn at the beginning of the 19th century. At the time, it began assuming the form of a museum collection thanks to the Prince Alessandro Torlonia. In 1866, the prince acquired the villa of distinguished Cardinal Alessandro Albani. The villa is in Rome, located along the Via Salaria. When the prince acquired the villa, he also purchased the impressive collections of paintings and Greek and Roman sculptures found within. By the end of the 19th century, the collection included an extraordinary number of ancient marbles. Around 1875, the Prince Alessandro promoted a project to establish a Museum of Ancient Sculpture in an old grain warehouse along Via della Lungara near Palazzo Corsini. Dubbed “Torlonia Museum” it was open to small groups of visitors. But the project didn’t last, since in 1976 the building was converted into housing units and the collection locked up. The 2020 exhibition will display artworks that have not been on view since the 1970s.

Nowadays, the celebrated Torlonia Collection is not publicly visible, but it is the “most important private collection of ancient sculpture existing in the world,” according to the well-known art historian and critic Federico Zeri. What’s more, it is significant for many fields of study, including art history, archaeology, collecting history, restoration and museology. Due to the high-quality and complex nature of several collection which joined it, the Torlonia Collection has been then called “the collection of all collections.”

The Value of the Extraordinary Exhibition

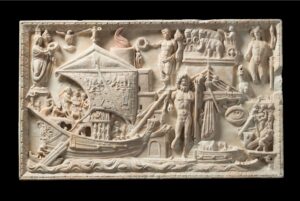

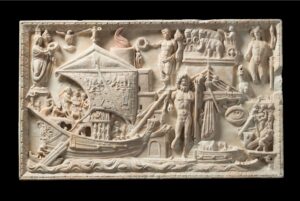

Porto relief, Torlonia Collection, ©FondazioneTorlonia, Ph. Lorenzo De Masi.

The anticipation surrounding this exhibition derives from many things. The art historical value of the sculptures themselves is incredible. The items include busts, reliefs, statues, sarcophagi, decorative elements and rare archaeological findings which have been always deemed as outstanding examples of ancient art. Also, the collection itself has an interesting history, as it was acquired over the centuries from a number of notable Romans. Moreover, the collection offers the opportunity to understand the prestigious and long history of antiquities collecting in Rome over a span of four centuries, between the 15th and the 19th century.

This is highlighted by the curators’ decision to configure the final room of the exhibition next to the Exedra of Marcus Aurelius, featuring the Lateran Ancient bronzes which were donated in 1471 by Pope Sisto IV’s to the “Roman People” and constituted the nucleus of what is considered as the first public museum in the world. In this way, the relationship between private collecting and public ownership are visually explained, highlighting the influential role of Rome in the art world.

A Torlonia Museum in Rome?

Statue of a goat at rest, Torlonia Collection ©FondazioneTorlonia, Ph. Lorenzo de Masi.

After being displayed at the newly restored exhibition venue at the Capitoline Museums in Rome, the traveling exhibit will tour around the world at a number of prestigious museums. As the details about these international agreements are revealed, the event schedule will be disclosed. It is also expected that the exhibition will end with the revelation of a permanent home in Rome, to be chosen by the Municipality of the City together with the Torlonia Family. This final home will permanently house the collection. This coveted collection will be yet another jewel in the crown of Rome’s artistic and cultural crown.

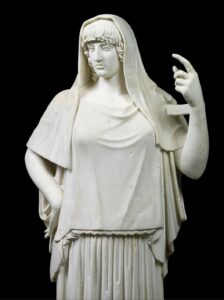

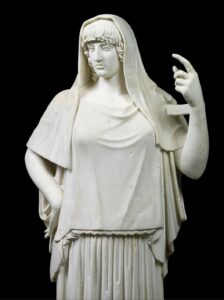

Hestia Giustiniani, Torlonia Collection, ©FondazioneTorlonia, Ph. Lorenzo De Masi.

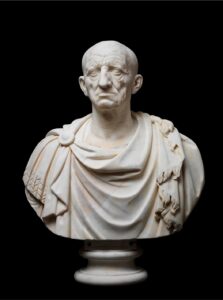

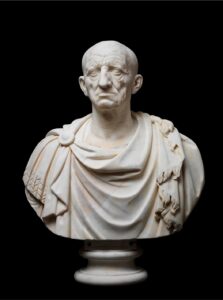

Old man from Otricoli, Torlonia Collection, ©FondazioneTorlonia, Ph. Lorenzo De Masi.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 6, 2020 |

Readers may recall from a previous blog post that Facebook Marketplace has become the subject of criticism for playing host to antiquities traffickers selling looted cultural heritage items online. Employing Facebook’s sophisticated algorithms, traffickers quickly connect with buyers receptive to purchasing plundered goods or with less experienced buyers who do not recognize the red flags associated with looted antiquities. Red flags include an origin from a conflict zone (such as Syria or Iraq), lack of provenance or export documents, and comparatively low prices in relation to the object’s scarcity or true value. Online sales have flourished after the looting of cultural heritage sites during and after the Arab Spring, and illicit trafficking of antiquities has been recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has left many cultural heritage sites defenseless and ripe for plunder. Antiquities as varied as scrolls, coins, and even mummified human remains are sold through online groups. More troubling is the fact that members would discuss how to illegally excavate historical sites. Some members provide tips on how to avoid law enforcement officials, while others make specific “loot to order” requests, deliberately targeting specific objects. The smuggling of Middle Eastern antiquities has been linked to terrorist groups and other crime syndicates. While physical border security may be tightened, it is more difficult to tackle online transactions.

As a result, groups like the ATHAR Project have been demanding changes. “Athar” is the Arabic word for antiquities, but the name also stands for “Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research.” Co-Directors Prof. Amr Al-Azm and Katie A. Paul have dedicated the project to ascertaining relationships between the digital underworld, transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The founders have spoken to media outlets to assist investigations into the issue. In response to this outcry, Facebook announced a change in policy to ban from its marketplace any “content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts.” The change was made effective as of June 23, 2020.

As a result, groups like the ATHAR Project have been demanding changes. “Athar” is the Arabic word for antiquities, but the name also stands for “Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research.” Co-Directors Prof. Amr Al-Azm and Katie A. Paul have dedicated the project to ascertaining relationships between the digital underworld, transnational trafficking, terrorism financing, and organized crime. The founders have spoken to media outlets to assist investigations into the issue. In response to this outcry, Facebook announced a change in policy to ban from its marketplace any “content that attempts to buy, sell, trade, donate, gift or solicit historical artifacts.” The change was made effective as of June 23, 2020.

Although the ban is an encouraging step towards the eradication of antiquities trafficking, Facebook’s decision is indicative of a larger problem facing the art market: the move to online sales spurred by developments in technology, and more recently the pandemic, has rendered the market more vulnerable to traffickers selling loot. Closing the Facebook Marketplace to “historical artifacts” is perhaps a well-intentioned gesture, but it fails to adequately address the concerns in the larger market. An expert was quoted as suggesting that Facebook should invest in specialized teams to identify and remove criminal networks at their source rather than “playing whack-a-mole with individual posts.”

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately, our client was victorious in defending itself against jurisdiction in the U.S.

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately, our client was victorious in defending itself against jurisdiction in the U.S.

On its face, banning cultural heritage items from Facebook Marketplace appears to be a responsible choice. In truth, Facebook is relegating a problem that it helped foster to nations that are already struggling to police the market. Critics of the ban argue that Facebook’s role in the illicit market makes the works more visible and easier for countries to locate. By closing its doors, Facebook has likely pushed these sales deeper into the black market, making them more difficult to track and recover. Further, Facebook indicated that it will not preserve information associated with the sale of artifacts, citing privacy concerns. This means that any information on the site will be destroyed rather than shared with countries of origin. Noting that “theft, pillage or misappropriation of” cultural property violates international law and constitutes a war crime, critics assert that social media evidence has been used by the International Criminal Court to prosecute and convict war criminals as recently as 2017. Facebook is ready to wash its hands of the market for looted antiquities, but in doing so, is neglecting the possibility of using its already established position to counteract the presence of looting on a more effective and direct basis.

The wooden sculptures, one male and one female, represent deities from the Igbo community. Copyright: Christie’s

Facebook is not alone in playing a troubling role in the illicit market. Whereas some traffickers exploit the dark recesses of the internet, others turn to the its most prominent levels in an attempt to legitimize a looted artwork. Due diligence measures have slipped during the COVID-19 pandemic, as buyers and intermediaries have been unable to inspect works personally. Recently, Christie’s was called upon by a prominent art historian to pull two Nigerian statues from a sale in Paris, believing the works were looted during civil war in the 1960s. At the very least, more information would be necessary to determine if the works had been exported illegally. Yet despite these concerns, Christie’s proceeded with the auction. Defending the sale, Christie’s maintained that there wasn’t “any suggestion that these statues were subject to improper export,” prior to the academic’s request. Unfortunately, this response side-steps an inconvenient truth that doubts about provenance may only surface once a work enters the global spotlight, as in an auction house sale. For instance, the lack of prior ownership claims may be due to the item being held in a private collection prior to sale. An official for the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments said he “was saddened” by the sale, but the country has not yet made a formal demand for repatriation. Despite the controversy, and perhaps encouraged by the lack of action by Nigeria, the piece sold for just under $240,000 (£195,000). Only time will tell whether the statues become the subject of litigation.

It is important for collectors to understand the particularities of acquiring antiquities, and it is important consult knowledgeable professionals to avoid problems. Amineddoleh & Associates has a wealth of experience addressing the challenges faced by foreign nations and private owners. Our founder has served as an expert for a number of high-profile repatriations. (She served as a cultural heritage law consultant in the return of thousands of looted artifacts to Iraq in the “Hobby Lobby” forfeiture, and as a cultural heritage law expert in matters such as the return of an Achaemenid relief to Iran, a golden coffin and mummy parts to Egypt, and a mosaic from one of Caligula’s ships to Italy.) This firm has represented museums, foreign nations, collectors, and sellers in litigations and transactional matters. Moreover, we routinely aid our clients in conducting due diligence to ensure that their purchases are legally permitted and free from encumbrance. As the pandemic continues and online cases soar, savvy purchasers must be as cautious as possible and contact legal counsel familiar with the art market’s pitfalls.

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

Stories of ghosts, demons, and other horrors are common to all cultures, and most cultures around the world have art portraying the supernatural. Since ancient times, Japan’s religion and culture has been deeply bound with ghosts, called yūrei. Both feared and revered, yūrei are part of the deep magic; a foundational belief that humans have a god inside of them.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

The manuscript is complete with Stoker’s original handwritten title, The Un-Dead (Stoker changed the title only days before the publication in 1897). The manuscript failed to sell went it went to auction in 2002 at Christie’s in NY. It is signed or initialled by Stoker in many places and contains a different ending to the final one published in 1897, and it was expected to fetch £1m. Since it failed to reach its undisclosed reserve price, it did not sell at auction. However, the novel was later sold privately through Christie’s to Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. Allen passed away in 2018, and the manuscript presumably remains in his estate.

As a result, groups like the

As a result, groups like the  As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately,

As Facebook’s abdication from the marketplace evidences, commercial actors are rarely incentivized to police their salesrooms. Further, the responsibility for reclaiming stolen property falls on the work’s country of origin. Even auction houses, which often carry out due diligence procedures, have been known to allow works with questionable provenance to reach the auction floor (more on this trend below). Relying on nations to recover looted works is problematic. Nations protect their heritage, often through a cultural ministry or national museum. Unfortunately, governments do not have the resources to investigate the global art market or recover property through litigation. Increasing the number of smaller, online sales makes this already Sisyphean task all the more impossible. Some nations monitor the market and confront sellers when questionable works appear on the market. Greece notably faced claims in federal court in New York after it communicated with an auction house about a suspicious item. Fortunately,