by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 26, 2021 |

Today, the Gilbert Trust for the Arts in London announced the return a 4,250-year-old Anatolian gold ewer from the Gilbert Collection to Turkey. The Gilbert Collection was created by Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001), who amassed an outstanding collection of British and European decorative arts that is currently on long-term loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A). Unbeknownst to Gilbert, the ewer was the product of illegal excavation and export. This came to light in 2019, after the Gilbert Trust for the Arts, which is responsible for managing the collection, performed an extensive provenance research project revealing the ewer’s connection to an unscrupulous antiquities dealer who concealed its true origins. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, played a role during this process as she shared her expertise in repatriation matters with the Gilbert Trust’s researchers and provided advice on what approach to adopt (based on legal and ethical grounds).

Today, the Gilbert Trust for the Arts in London announced the return a 4,250-year-old Anatolian gold ewer from the Gilbert Collection to Turkey. The Gilbert Collection was created by Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001), who amassed an outstanding collection of British and European decorative arts that is currently on long-term loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A). Unbeknownst to Gilbert, the ewer was the product of illegal excavation and export. This came to light in 2019, after the Gilbert Trust for the Arts, which is responsible for managing the collection, performed an extensive provenance research project revealing the ewer’s connection to an unscrupulous antiquities dealer who concealed its true origins. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, played a role during this process as she shared her expertise in repatriation matters with the Gilbert Trust’s researchers and provided advice on what approach to adopt (based on legal and ethical grounds).

As a result of its discussions with the Turkish Ministry of Culture, the Gilbert Trust officially donated the ewer to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara and commissioned a leading contemporary metalsmith to create a piece addressing the object’s history, to be displayed at the V&A in December. This recreation will allow the ewer to remain present in the museum’s galleries and initiate a constructive dialogue on the importance of proactive provenance research, collaboration, and exchange. While other institutions are sometimes wary of repatriating objects without a legal requirement to do so, the Gilbert Trust’s actions demonstrate that it is possible to return cultural objects in a way that is both respectful to current possessors and takes the source country’s wishes into consideration, leading to a mutually beneficial solution.

The Ewer’s Provenance

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece.

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece.

In fact, Bruce McNall – the antiquities dealer who sold the work to Gilbert – later admitted to smuggling ancient artifacts out of source countries like Italy, Greece and Turkey. He worked alongside his partner, Robert E. Hecht, to sell items to unsuspecting buyers. McNall is a colorful figure who once owned Thoroughbred racehorses as well as sports teams (the Los Angeles Kings of the National Hockey League and the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League), enjoying a great deal of commercial success. However, his fall from grace in the early 1990s after defaulting on a $90 million loan resulted in bankruptcy and a 6-year stint in prison. McNall’s autobiography, published in 2003, details his partnership with Hecht and offers a glimpse into the world of illicit antiquities trafficking. According to the book, at one point Hecht occupied the dubious honor of being the world’s largest source of recently discovered antiquities, which he was able to procure thanks to monetary resources and an extensive network of grave robbers, smugglers, and intermediaries. Once items were obtained, they passed through countries without export controls and then onto Hecht, who sold them on to a collector or dealer. In order to sell the illusion that an item’s provenance was above board, Hecht would spin tales about its location in private homes and the like for the past several decades. As his reputation – and notoriety – increased, buyers would come to Hecht knowing that he could procure rare and valuable pieces. This included McNall, who later opened a gallery on Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles supplied mainly by Hecht’s dubious dealings. Both men drove the market for ancient art amongst the wealthy, creating false sales receipts and invoices from foreign-based companies (usually set up by McNall and Hecht) to cover their tracks.

Notably, Hecht was also tied to the Euphronios Krater later returned to Italy by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2005, Hecht was charged with trafficking in looted antiquities alongside former Getty Museum curator Marion True and Italian dealer Giacomo Medici, but the case was dismissed in Italian court because the statute of limitations expired before the verdict was issued. He moved to Paris in the wake of the scandal, where he eventually passed away in 2012 – although his legacy lives on in the remaining looted objects that passed through his hands and are dispersed throughout the world.

The Importance of Provenance Research

During the period when McNall and Hecht were active, provenance research was not given the same importance it holds today. For the majority of purchasers, including museums, not asking in-depth questions about provenance or looking the other way when confronted with suspicious ownership histories was considered the norm. However, nowadays museums and private collectors increasingly acknowledge the crucial role of provenance research in upholding the legitimacy and ethical role of cultural institutions as stewards for the public.

It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.

It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 23, 2021 |

As a leading law firm in the NFT space with expertise in both art and intellectual property law, Amineddoleh & Associates LLC was selected to draft Monax’s template for the purchase and sale of NFTs.

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is pleased to announce that it is working with Monax to further the company’s mission to deliver a comprehensive and cutting-edge digital contract platform that meets discerning users’ needs. Monax is a major player operating in the smart contracts market. It allows users to access and track agreement templates, as well as manage their contractual obligations throughout the life cycle of the contract. The model uses a combination of smart contract programming, blockchain technology, and business process modeling to offer users a unique, sophisticated tool to streamline and automate business contracts. It also reduces the likelihood of confusion and friction between contractual parties because the language is clear and accessible.

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is pleased to announce that it is working with Monax to further the company’s mission to deliver a comprehensive and cutting-edge digital contract platform that meets discerning users’ needs. Monax is a major player operating in the smart contracts market. It allows users to access and track agreement templates, as well as manage their contractual obligations throughout the life cycle of the contract. The model uses a combination of smart contract programming, blockchain technology, and business process modeling to offer users a unique, sophisticated tool to streamline and automate business contracts. It also reduces the likelihood of confusion and friction between contractual parties because the language is clear and accessible.

As part of this initiative, our team was hired by Monax to create a template agreement for the sale of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs). NFTs are a new digital asset class ranging from artwork to GIFs, memes, Tweets, and even video clips of sporting events. Because they are tied to blockchain and cryptocurrency, NFTs straddle the divide between traditional and emerging property types, requiring a new way to deal with such transactions. As a result, Monax has implemented our one-of-a-kind template on its website as a resource for users who are buying and selling NFTs. NFTs identify and certify digital assets as unique items. While the digital image can still be duplicated, the NFT monetizes the images by allowing a buyer to purchase the unique token and, with it, ownership of the original digital object. There has been a growing market for art collectors who are buying and collecting NFTs like they would art, and in some cases, buying them for millions.

However, because NFTs are such innovative assets, collectors, purchasers, artists, and sellers all need contracts that protect their rights and accurately describe what is being included in the transaction. For instance, the purchase of an NFT does not automatically grant the buyer intellectual property rights in the original image (or video). An NFT agreement also offers artists the opportunity to obtain future royalties and exert greater control over their work. Depending on the parties’ specific needs, and the type of NFT in question, a more simple or complex contract may be required.

CryptoPunks NFTs (Larva Labs)

As a law firm specializing in art and intellectual property transactional and litigation matters, we were hired by Monax to draft its template, one of the first of its kind, because of our in-depth knowledge resulting from our continued work with artists, buyers, and sellers in the art world. As this new market continues to boom, we were pleased to draft the company’s novel template that is now available for future NFT buyers, sellers, and creators. Please note that our NFT template created for Monax is only a template, not a final agreement. Every sales transaction is unique and requires specific legal analysis necessitating nuanced transactional documents. We advise all artists, buyers, and sellers to consult with legal counsel prior to entering into an arts transaction.

In addition to the Monax template, our firm reviewed intellectual property terms and conditions for highly popular NFT marketplace Nifty Gateway, and we are currently developing other exciting NFT projects, such as a creative collaboration between a visual artist and well-known musician. As NFTs continue to evolve and grow within the digital marketplace and the art world, we look forward to participating in more projects and expanding our reach in this exciting new space.

If an effort to educate art market professionals about NFTs, Leila A. Amineddoleh will be discussing NFTs, luxury goods, and emerging technologies during the Art Law & Provenance module of the EXECUTIVE MASTER IN ART MARKET STUDIES at the University of Zurich.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 5, 2021 |

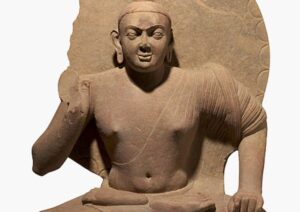

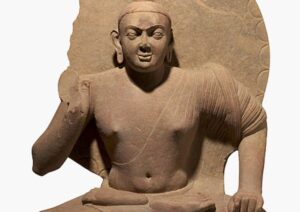

Indian relief seized from the Nancy Wiener Gallery in Manhattan.

(Photo Credit…Manhattan District Attorney’s Office)

Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, spoke with the New York Times today about important revelations from statements submitted to the New York County Supreme Court by antiquities dealer Nancy Wiener during the pending criminal case against her. After pleading guilty to charges of conspiracy and possession of stolen property in connection with the trafficking of looted treasures from India and Southeast Asia, Ms. Wiener filed an allocution statement that reveals the inner workings of the antiquities market. (After pleading guilty, a defendant is often offered an opportunity to address the court in a so-called allocution statement to accept responsibility, express remorse, and explain circumstances that might be considered favorably in sentencing.)

Ms. Wiener and her late mother sold works to the New York elite. They are credited with growing the market for Southeast Asian art, selling works to John D. Rockefeller III, Igor Stravinsky and Jacqueline Kennedy. Works from their gallery also appear at major museums nationally and internationally. In March 2015, Ms. Wiener reimbursed the National Gallery of Australia over a million dollars for a Buddha she had sold the institution in 2007, after it was discovered that the export of the item may have violated India’s laws.

National Gallery of Australia’s Seated Buddha (Photo Credit: Chasing Aphrodite)

In 2016, federal officials and the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office raided a number of galleries during Asia Week in New York. One of those galleries belonged to Ms. Weiner. The government seized objects from her gallery, arrested Ms. Wiener, and filed a felony complaint accusing the dealer of working with stolen objects for decades. Amineddoleh has spoken about the criminal case against Ms. Wiener in the past, including in 2017 when she was invited to speak during a conference for the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The charges allege that Ms. Wiener obtained millions of dollars’ worth of stolen artifacts from international smugglers and sold them illegally — often through major auction houses. She is alleged to have laundered the illicit items by procuring restoration services to hide damage from illegal excavations, using straw purchases at auction houses to create sham provenances, and inventing and disseminating false histories to circumvent international patrimony laws that prohibit the exportation of looted antiquities. Upon her mother’s death, Ms. Wiener allegedly inherited hundreds of illicit items, discarded their records, and fabricated provenances. She then consigned hundreds of lots for sale at auction for millions of dollars.

In pleading guilty to these allegations, Ms. Weiner’s allocution statement reveals a great deal about the antiquities market. She characterizes that market as “a conspiracy of the willing,” saying that antiquities are often sold or consigned despite having suspect provenance — or no provenance at all. She also admits in detail to committing the common (and illegal) practice of fabricating provenance information to facilitate the sale or consignment of looted items. Despite claiming that her actions were motivated by her “passion” for the “great beauty” of historical objections, Ms. Weiner acknowledges that “it is not the right of any individual or institution to decide how to handle the cultural patrimony of another nation.”

Read more about the case in this article by Tom Mashberg.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Aug 23, 2021 |

In the latest entry of our firm’s ongoing Provenance Series, we discuss a new Polish law that will likely have serious negative implications for claimants seeking the return of property looted during the Second World War. In order to understand the context giving rise to this law, we delve into the country’s history of cultural heritage looting from 1939-1993, recent restitution cases, the provenance of the famous Czartoryski Collection, and the potential effects of Poland’s new law on lawsuits involving Nazi looted art and cultural heritage.

The Sacking of Poland’s Cultural Property During and After WWII

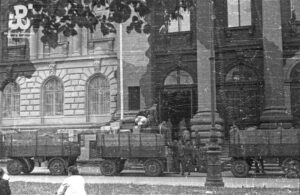

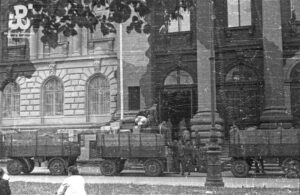

Germans looting the Zachęta Museum in Warsaw in the summer of 1944

It has been estimated that Poland suffered the staggering loss of 70% of its tangible cultural heritage during WWII at the hands of both the Nazis and the Soviet Union. This unprecedented loss amounts to approximately 500,000 cultural objects; many still unaccounted for, including masterpieces by Raphael, Albrecht Durer, Rembrandt, and other beloved Old Masters. The looting campaign was systematic, as the Nazis had a plan in place before invading Poland in 1939. Seizures were overseen by high-ranking officials, and then exacerbated by the Soviet Army and its subsequent decades-long occupation. Although the Nazis kept extensive documentation of their newly acquired spoils, much of the goods and records were lost during their evacuation of the Polish territories in 1944 and the ensuing turmoil. While the confiscations involved many Jewish families, not all property belonged to this minority; Christians, Roma, and political dissidents were also targeted. To illustrate, in 2007 a Polish count made a claim to a medieval cross worth $500,000 that was found in the trash in Austria, which had previously been forcibly removed from Poland. (The count is a member of the aristocratic Czartoryski family, whose collection is discussed below.)

Thus, restitution is a complex and sensitive subject given the horrific scale of suffering experienced by the Polish population both during and after WWII. A core factor complicating the return of cultural objects is the confiscation of such items by the Communist regime in the years after WWII, as Poland was not considered a sovereign nation with the capacity to enforce its national laws, particularly with respect to private property, until 1993. In some ways, the Communist mentality is still felt with regards to state-controlled property, including cultural objects. It is important to note that under Poland’s patrimony laws, dating as far back as 1918, cultural heritage is generally considered sovereign property. Therefore, recovery efforts are typically aimed at tracking down works for future custody and display in national museums and collections.

An additional obstacle is that class action suits to recover property from victims without heirs are regarded as incompatible with Polish law, as in the case of international Jewish organizations that claim property taken from Jews that have no living descendants. All these factors have resulted in Poland lagging behind other countries regarding the restitution of WWII-looted objects, despite some success stories (discussed below), and their cooperation with international organizations and law enforcement. Overall, the restitution process is expensive and time consuming for claimants, and the new law imposing a strict statute of limitations on claims will create further hindrances.

Polish Law and Difficulties in Returning Nazi Looted Cultural Heritage

Portrait of a Seated Woman by Thomas Couture (Photo courtesy of the German Lost Art Foundation)

Over the past decade, the Polish government has increased its efforts to recover looted cultural items from collections abroad. In 2011, the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage’s Division of Looted Art created a website to publicize its recovery efforts and assist in identifying missing works. The Division manages the only national cultural database of wartime losses and has gathered information on over 63,000 objects including paintings, coins, vehicles, sculpture, books, maps, toys, carpets, furniture, metalwork, and jewelry, among other items of artistic, historical, and sentimental value. The public can also access the list of recovered artworks online and use the Art Sherlock app to identify stolen or looted works. In 2012, it was announced that one of the most famous missing pieces, Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man, had been supposedly found in a bank vault in an undisclosed location. However, it still has not entered the public eye. (One of our previous blog posts discusses the provenance of this fascinating work in more detail.) Moreover, this type of information gathering is time-consuming and requires both willing participation and accurate data. Collectors, dealers, and purchasers may be wary of publicly submitting such details if they come to realize that the provenances of works in their possession are problematic.

Another challenge for restitution claims is the applicable statute of limitation. Statutes of limitation are meant to ensure that a party is not prejudiced by another party’s undue delay or inaction in making a claim. In theory, this helps prevent false or outdated claims from commencing after proof has been lost or blurred by the passage of time. However, the strict application of statutes of limitations to Nazi looted property seems unjust and unfair, as a stolen item’s whereabouts are typically unknown for extended periods of time. If a private collector is in possession of such items, they may be hidden for years away from public view. Unless they are sold on the open market, for all intents and purposes, the works will have disappeared.

The Gurlitt Trove

A notorious example of this phenomenon is the “Gurlitt Trove,” containing nearly 1,400 works worth approximately $1.35 billion and which was discovered in 2012. Cornelius Gurlitt inherited the pieces from his father, an art dealer linked to the Nazis, and stashed them away for decades. After a chance cash check during a train journey, authorities became suspicious of tax evasion and raided Gurlitt’s apartment where they found a treasure trove or art. Gurlitt refused to return the works and argued that lawsuits would be blocked on statute of limitations grounds. Under German law, if a court found that Gurlitt was a good faith purchaser, he would have been entitled to keep the objects. Gurlitt ultimately reached an agreement with the Bavarian state prosecutor to return certain works to the heirs of their former owners. After his death in 2014, it was discovered that Gurlitt had bequeathed his collection to a Swiss museum. The German Lost Art Foundation, an organization founded by the German government, spent the next 6 years performing provenance research on the collection and identified several looted works that were then returned. These included Portrait of a Seated Woman by Thomas Couture (returned in January 2019 due in part to a tiny detail in the work) and Quai de Clichy by Paul Signac (returned in July 2019). Sadly, only a handful of works have been restituted to date because of the difficulty in obtaining accurate provenance information.

The Gurlitt controversy demonstrates that applying strict time limitations to claims may undermine the purpose of Holocaust-related restitution doctrines, which is to seek justice for those who were violently targeted by the Nazis. The Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, drafted in 1998, encourage participating nations to return looted art to original owners or their heirs. Steps should be taken to achieve a just and fair solution, according to the circumstances of each specific case. While these principles are non-binding, they recognize that moral claims have a role to play in lawsuits concerning Nazi looted cultural property.

New Legislation in Poland

These issues have now been exacerbated by recent Polish legislation. Just this month, Polish President Andrzej Duda signed a law reducing the statute of limitations on all restitution cases to 30 years since the theft’s occurrence. In practical terms, this means that restitution of Nazi-looted items will become impossible since the thefts occurred nearly 80 years ago. Both the U.S. and Israeli governments, in addition to many cultural heritage experts, have denounced the decision. Although the law was criticized as “immoral” and a “disgrace,” the Polish government has defended its actions by saying that the new rules aim to end fraud and stop irregularity concerning property restitution, which the President terms “an era of legal chaos.” Last week, our founder was quoted in Artnet regarding the “overwhelming obstacles” victims in restitution cases face, including how proving legal title to stolen art decades later in a court of law is a tremendous challenge. The new law fails to account for these obstacles and the practical difficulties in overcoming them.

The Polish legislature could potentially carve out an exception for Holocaust looted property to prevent outstanding claims from being blocked, but the current law treats all property equally. The law has additionally been characterized as problematic for seemingly undermining Poland’s own efforts to recover cultural items at the national level. We discuss recent examples of returned Polish cultural property in the following two sections as a counterpoint to the new law.

A Spanish Museum Returns Flemish Paintings to Poland

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain announced that it would return two paintings by Flemish artist Dieric Bouts to Poland. The late 15th Century works depict the Virgin of Sorrows and Jesus Christ in his Ecce Homo aspect. They were purchased from one of the museum’s patrons who likely acquired them from a Spanish dealer in the 1970s. The paintings were displayed openly for years, without any suspicion regarding their origins. Then, in late 2019 the museum was alerted by Polish authorities that the paintings closely resembled ones looted by the Nazis that were destined as a gift for Hitler. It is unclear when or how the paintings arrived in Spain, but it is certain that they were taken by the Nazis from the medieval Goluchów Castle in Poznan since they appeared in a German inventory of the country’s most valuable cultural items during WWII. After receiving notification from Poland, the museum engaged a team of experts to examine the works, which were found to match the missing items.

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain announced that it would return two paintings by Flemish artist Dieric Bouts to Poland. The late 15th Century works depict the Virgin of Sorrows and Jesus Christ in his Ecce Homo aspect. They were purchased from one of the museum’s patrons who likely acquired them from a Spanish dealer in the 1970s. The paintings were displayed openly for years, without any suspicion regarding their origins. Then, in late 2019 the museum was alerted by Polish authorities that the paintings closely resembled ones looted by the Nazis that were destined as a gift for Hitler. It is unclear when or how the paintings arrived in Spain, but it is certain that they were taken by the Nazis from the medieval Goluchów Castle in Poznan since they appeared in a German inventory of the country’s most valuable cultural items during WWII. After receiving notification from Poland, the museum engaged a team of experts to examine the works, which were found to match the missing items.

The museum indicated it would return the works to Poland. Polish authorities commended the museum’s willingness to do so voluntarily, even though it had acquired them in good faith (as such, the museum had a legal claim of ownership under Spanish law). The case was cited as an example of integrity and transparency. César Mosquera, vice president of the Pontevedra city council, announced that they were proud to return these works in light of their dark origins.

The Provenance of the Czartoryski Collection

Lady with an Ermine, Leonardo da Vinci

The famed Czartoryski Collection has reached mythical proportions in Poland, not only due to the breadth of its works, but also the family’s travails. This aristocratic family is closely tied to the political and cultural history of the Polish state. In 1796, Princess Izabella Czartoryska opened the first Czartoryski Museum at her residence in Pulawy, showcasing her antiques and paintings. Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine and Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man formed part of this esteemed group. During the Russian occupation of Poland in 1830, the family fled and ultimately resettled in Paris. While the Raphael painting was lost, the Princess saved the Leonardo by sending it 100 miles south to the Czartoryski palace at Sieniawa, before it joined the family in Paris. The Czartoryskis returned to Poland and opened another two museums by 1878, one in Warsaw and one in Goluchów Castle. The Castle collection consisted of over 5,000 decorative art objects and several hundred valuable paintings. In 1939, as the Nazis approached Poland, the widow of Prince Adam Ludwik Czartoryski removed the most valuable works from the castle, concealed them in 18 boxes, and hid them behind a wall in the wine cellar. However, Nazi officials coerced her into revealing the objects’ location. The Nazis confiscated the items and moved them to the National Museum of Warsaw in 1941, where they were inventoried and photographed. Some of the pieces were taken to Austria, while others were pillaged by deserters and refugees at the end of the war. Lady with an Ermine was fortunately returned in 1946, after its discovery by Allied soldiers (the Monuments Men) in Germany. Unfortunately, the collection was then under the Communists’ control until the fall of the Soviet Union. The family has spent decades attempting to track down their treasures. Prince Adam Karol Czartoryski, born and raised in Spain, has made it his life’s mission to recover what was stolen and established the Princes Czartoryski Foundation in 1991 for this purpose.

In 2016, the Prince signed an agreement with the Polish government selling the collection of 86,000 artworks and 250,000 historic manuscripts to the state for €100 million (a fraction of its total value). It was considered a tremendous bargain for Poland, and the sale was hailed as a donation. The agreement stipulated that the National Museum in Krakow would control the buildings owned by the Czartoryski family and used for the display of the works, and the collection was made publicly available in 2019 after extensive renovations. Despite some controversy over the nature of the purchase, the collection now attracts visitors from all over the world. The government also signed a separate agreement with the Czartoryskis for the acquisition of Goluchów Castle and its art collection. However, the family retains the right to make claims for the return of still-missing looted cultural objects, estimated at 800 pieces. This means that cases involving the Czartoryski collection could arise in the future, whether in Poland or abroad.

The Future of Polish Restitution and its Effects in the U.S.

Warsaw Castle (photo courtesy of Claudia Quinones)

Poland has received criticism for lacking viable procedures to process restitution claims from Holocaust victims, within the country and from abroad. It has also failed to uphold the Washington Principles despite benefiting from restitution laws of other nations, including the U.S. This, combined with the new law’s restrictive statute of limitations, may prompt claimants to file lawsuits in more forgiving jurisdictions, such as the U.S. (however, jurisdictional challenges remain for claimants to prove proper jurisdiction within the U.S.). Restitutions of Nazi-looted art involving foreign claimants have become prominent in the U.S., including the well-known cases of the Altmann family’s claim to Klimt’s Lady in Gold and the ongoing Guelph Treasure litigation. The statute of limitations for theft in general may be tolled under the Demand and Refusal Rule or the Discovery Rule. The Demand and Refusal Rule, which only applies in New York, holds that the statute of limitations begins to run when the original owner demands restitution, and the current possessor refuses to return the object. The Discovery Rule deems that time begins to run when an owner knows or reasonably should know the location of the object.

At the federal level, U.S. Congress passed the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016 (HEAR Act) providing a 6-year statute of limitations for Nazi looted cultural property that does not begin to run until the object in question is actually discovered and knowledge of it is obtained. This is more favorable for claimants, allowing them greater opportunity to make plans of action for restitution. Notably, the Act has the potential for cases that were previously barred under statute of limitations rules to be “resuscitated” in special circumstances. However, while the Act replaces state and federal statutes of limitations for art recovery claims with a uniform period to make a claim, this is only temporary (until 2026).

The HEAR Act also allows claimants to side-step the good faith purchaser loophole present in many countries, including Poland. The U.S. follows the nemo dat rule, holding that a thief cannot transfer good title to stolen property. This fault in title continues to taint subsequent purchasers. If claimants have a connection with the U.S., they may be able to file a suit for the restitution of looted cultural property there, even if the object is located in another state such as Poland. Likewise, Poland could appear in a U.S. court to request repatriation if there is sufficient nexus, or the nation may request assistance from U.S. authorities. For example, in 2014, the FBI was contacted by Poland and tracked down 75 paintings by a Polish resistance fighter who moved to San Francisco after escaping a concentration camp. Although Poland’s law may affect domestic claims, the door remains open for international cooperation, which may have a more favorable outcome.

The effects from the Polish law remain to be seen, but there is no stemming the tide of restitution for Nazi looted cultural heritage. Although countries have experienced setbacks with restitution claims, cultural heritage attorneys will continue to seek justice in the face of procedural and legal hurdles.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 14, 2021 |

Virtual restoration of the Old Summer Palace during the Qing Dynasty, 1644-1911. (Copyright: Asianewsphoto)

Over two thousand years ago, the Jade Emperor, Supreme God of the Heavens in Taoism mythology, launched what is now known as the Great Race. The invitation was extended to every animal species in the Empire but, because of prior engagements or travel restrictions, only twelve (the Pig, Rooster, Sheep, Horse, Dog, Monkey, Snake, Rabbit, Dragon, Tiger, Rat, and Ox) attended the event. In gratitude, the Jade Emperor promised each participant it would be attributed a zodiac year and two hours of the day. The first to reach the finish line would become the first zodiac sign and the first two hours of the day, and so on. The race crossed all terrains, with its climax being a river crossing. Rat, the group’s smallest member, feared for its life; until it spied Ox. The bovine was known to have poor vision so Rat offered to direct it through the river by riding on its back. Ox agreed and they began the final leg of the journey. Yet once the pair grew close to the opposite bank, Rat jumped off Ox’s head and won the race. To this day, Rat remains the first sign in the Chinese zodiac and it symbolizes hours 11:00pm to 1:00am.

Under the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, Emperor Qianlong commissioned the creation of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. Reigning over 715 acres of utopian hills and gardens, the palace hosted the empire’s formal and recreational stays. Within this land, hidden in the Garden of Eternal Spring, was the Haiyantang water-clock fountain. Giuseppe Castiglione, an Italian painter, designed the fountain to include twelve bronze heads in the shapes of the zodiac animals, which sprouted water at the hours to which the creatures were assigned in the Great Race myth. Water speared out of Rat’s mouth at midnight and Rabbit rose with the sun from 5:00 to 7:00am.

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.

World-renowned French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé spent years acquiring an enviable art collection. From their first acquisition of a wooden bird sculpture, Oiseau Sénoufo, originating from Côte d’Ivoire in 1960, animals became a central theme in their collection. When Saint Laurent died in 2008, Bergé auctioned off a large part of their collection with Christie’s Paris the following year. Up for auction were the rat and rabbit heads. They may have gone unnoticed, but the Republic of China had had its eyes out for the bronzes for nearly a decade. Back in 2000 the tiger, the monkey, and the ox were the first zodiac heads to reappear on the public art market. At the time, they were featured in Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction catalogues for their upcoming sales. The Chinese State Bureau of Cultural Relics promptly wrote to the auction houses demanding the withdrawal of the bronze heads from the sales. The Chinese government did not formulate an official restitution request because international conventions were viewed as inapplicable to lootings that occurred over 140 years ago. As a result, the auction houses rejected the State’s request. In an unexpected turn of events, however, China Poly Group Corp. Ltd.placed its live bids on all three heads, and won them for a total of $4 million dollars. The sculptures were placed in this state-owned corporation’s Poly Art Museum in Beijing, which is dedicated to Chinese heritage. Three years later, the same museum acquired the pig head from Chinese billionaire Stanley Ho, who had bought it from a New York collector. Finally, in 2007, Ho purchased the horse head from Sotheby’s Hong Kong for $8.9 million dollars.

Jackie Chan wrote, directed, and starred in a film about the stolen zodiac bronzes.

It came as no surprise when Christie’s Paris received a letter from the Chinese government in February 2009 asking that the rat and rabbit heads be removed from the Yves Saint Laurent-Bergé sale. It was also to be expected that the auction house would refuse. In protest, the “Association pour la protection de l’art chinois en Europe” (the Foundation for the protection of Chinese art in Europe) along with eighty other Chinese lawyers, filed a complaint with the “juge des référés” whose role in France is to deliver temporary restraining orders in time-sensitive situations. Two days before auction, the tribunal rejected the foundation’s request to enjoin the sale.

THE PROVENANCE: In its press release on the three-day Saint Laurent estate sale, Christie’s described the zodiac bronze heads as the “two main pieces” amongst the works for sale. The sculptures’ provenance revealed that Saint Laurent had acquired them from the Kugel brothers at their famous Galerie Kugel in Paris. The Kugels bought the bronze heads from the marquis de Pomereu in 1986 who had attained them from the Spanish painter José María Sert.

On the closing day of the sale, February 25, 2009, the rat and rabbit bronzes sold for the equivalent of nearly $40 million. A few days later, the winning bidder refused to pay for them. Cai Mingchao, a self-described Chinese patriot, explained his act was a national duty. “This money,” he claimed, “should not be paid.” The Chinese government publicly supported Mingchao’s fraud and, in addition, placed tighter trade restrictions on Christie’s art trades, ordering local law enforcement officials to report any artifact that might have been looted and trafficked. Following Mingchao’s refusal to pay for the sculptures, Pierre Bergé eventually sold the lots to French billionaire François Pinault, the owner of Christie’s.

Rabbit bronze for auction at Christie’s (Copyright: Agence France-Presse)

However, the story was not over. In 2013, Pinault announced that the rat and rabbit heads would return to Beijing. But the animals’ race home came at a price. Curiously, this donation occurred only a few days after Christie’s was granted a license to conduct business on mainland China. Most recently, in December 2020, China’s National Cultural Heritage Administration launched the return of the horse head. The Summer Palace was restored in 1886, twenty-six years after its destruction. However, the dragon, dog, sheep, snake, and rooster have yet to reach to finish line and return home.

Today, the Gilbert Trust for the Arts in London announced the return a 4,250-year-old Anatolian gold ewer from the Gilbert Collection to Turkey. The Gilbert Collection was created by Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001), who amassed an outstanding collection of British and European decorative arts that is currently on long-term loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A). Unbeknownst to Gilbert, the ewer was the product of illegal excavation and export. This came to light in 2019, after the Gilbert Trust for the Arts, which is responsible for managing the collection, performed an extensive provenance research project revealing the ewer’s connection to an unscrupulous antiquities dealer who concealed its true origins. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, played a role during this process as she shared her expertise in repatriation matters with the Gilbert Trust’s researchers and provided advice on what approach to adopt (based on legal and ethical grounds).

Today, the Gilbert Trust for the Arts in London announced the return a 4,250-year-old Anatolian gold ewer from the Gilbert Collection to Turkey. The Gilbert Collection was created by Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001), who amassed an outstanding collection of British and European decorative arts that is currently on long-term loan to the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A). Unbeknownst to Gilbert, the ewer was the product of illegal excavation and export. This came to light in 2019, after the Gilbert Trust for the Arts, which is responsible for managing the collection, performed an extensive provenance research project revealing the ewer’s connection to an unscrupulous antiquities dealer who concealed its true origins. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, played a role during this process as she shared her expertise in repatriation matters with the Gilbert Trust’s researchers and provided advice on what approach to adopt (based on legal and ethical grounds). Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece.

Not only is the ewer a stunning example of ancient metalwork, it also possesses a fascinating history. This masterpiece was created by a Hattian goldsmith living in Anatolia over 4,000 years ago. The ewer was formed by embossing a single sheet of gold with complex patterns, including an ancient symbol of the sun, in order to accompany a Hattian ruler into the afterlife. When Gilbert acquired the ewer in 1989, he was dazzled by the evocative story as well as its beauty. However, because Gilbert was not very experienced in collecting these types of objects (this was the only archaeological object he ever bought), the seller was able to conceal the ewer’s illicit origins and misrepresent the origins of the piece. It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics.

It is commendable when a collection proactively engages in discussions with foreign entities to right a past wrong. By following this course of action, it is possible for all stakeholders to determine the best outcome for displaced antiquities, without resorting to contentious and costly litigation (an expense that is burdensome for both private institutions and government entities). As such, creative results are possible, as in the Gilbert Trust’s agreement with Turkey. The Gilbert Trust made the decision to engage in proactive discussions with Turkey, a nation known to aggressively protect its cultural heritage and demand the repatriation of looted objects. However, by digging deeper into its collection to understand their histories, the ewer will finally return to its home, the Gilbert Collection will retain its unblemished reputation, and the V&A is engaging the public in discussions concerning ownership, history, and museum ethics. Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is pleased to announce that it is working with Monax to further the company’s mission to deliver a comprehensive and cutting-edge digital contract platform that meets discerning users’ needs. Monax is a major player operating in the smart contracts market. It allows users to access and track agreement templates, as well as manage their contractual obligations throughout the life cycle of the contract. The model uses a combination of smart contract programming, blockchain technology, and business process modeling to offer users a unique, sophisticated tool to streamline and automate business contracts. It also reduces the likelihood of confusion and friction between contractual parties because the language is clear and accessible.

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is pleased to announce that it is working with Monax to further the company’s mission to deliver a comprehensive and cutting-edge digital contract platform that meets discerning users’ needs. Monax is a major player operating in the smart contracts market. It allows users to access and track agreement templates, as well as manage their contractual obligations throughout the life cycle of the contract. The model uses a combination of smart contract programming, blockchain technology, and business process modeling to offer users a unique, sophisticated tool to streamline and automate business contracts. It also reduces the likelihood of confusion and friction between contractual parties because the language is clear and accessible.

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain

Earlier this year, the Museum of Pontevedra in Spain

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.

In 1856, the British declared the Second Opium War against the Qing government. The French joined soon after. Four years into the war, British High Commissioner to China, James Bruce, the Eight Earl of Elgin entered the picture. The son of the Thomas Bruce (known for removing from marble frieze from the Parthenon), James Bruce ordered the burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace. Like his father, James has faced the ire of history due to his destruction and theft of a nation’s heritage. He knew that amongst the Chinese Palace’s treasures, the fountain’s bronze heads were no small catch. The French and British soldiers likely traded some of the loot amongst themselves. We now know most of the bronze heads were sent to Europe.