by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 1, 2022 |

A visit to the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto, MArTA) reminded me why I love museums so much. It is an inspiring place, a valuable educational resource, and an underappreciated repository for art and heritage.

Taranto, Italy

Greek ruins (Temple of Poseidon)

MArTA is located in Taranto, a city located along the inside of the “heel” of Italy in the region of Puglia. It was founded by Spartans in 706 BC, and it became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia (the Roman-given name for the coastal areas in the south of Italy — Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily — heavily populated by Greek settlers). Two centuries after its founding, it was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of around 300,000 people. Taranto (called Tarentum by the Ancient Romans) was subject to a series of wars, culminating in its fall to Rome in 272 BC. The city fell to Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but was recaptured (and subsequently plundered) by Rome in 209 BC. The following centuries marked the city’s decline.

Cathedral of San Cataldo

Taranto’s mix of architecture and rich cultural heritage is due, in part, to subsequent changes in leadership between the 6th and 10th centuries AD, during which time it was ruled by diverse groups: Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Arabs. Later, during the Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century AD, the city served as a French naval base, but it was ultimately returned to the Kingdom of Two Sicilies for a few decades before it officially became part of the Republic of Italy in 1861.

Due to its strategic location on the inlet of the Gulf of Taranto, the city has great naval importance. Taranto served the Italian navy during both World Wars. As a result, it was heavily bombed by British forces in 1940 (the bombing of Taranto and was even noted to have “set the stage for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor” the following year). The city was also briefly occupied by British forces during WWII.

Evidence of the city’s various iterations is evident throughout its streets with impressive cultural sites, including the Greek Temple of Poseidon, the Spanish Castello Aragonese (built in 1496 for the then-king of Naples, Ferdinand II of Aragon), and the 11th century Cathedral of San Cataldo (Taranto Cathedral), where the remains of the city’s patron saint, Saint Catald, lie (he is believed to have protected the city against the bubonic plague). More recent architectural gems include Palazzo Galeota and Palazzo Brasini.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MArTA)

Like the city where it is located, MArTA is a rich institution full of incredible treasures. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit MArTA in person. Sadly, the museum, and the city itself, tend to fall under the radar of tourists. It is unfortunate that this site escapes attention, because both Taranto and its vaunted museum are incredible.

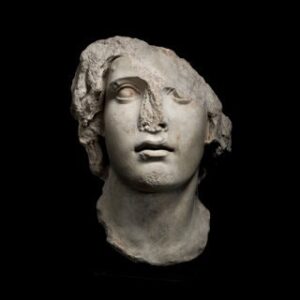

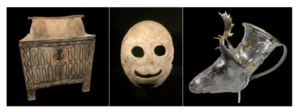

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

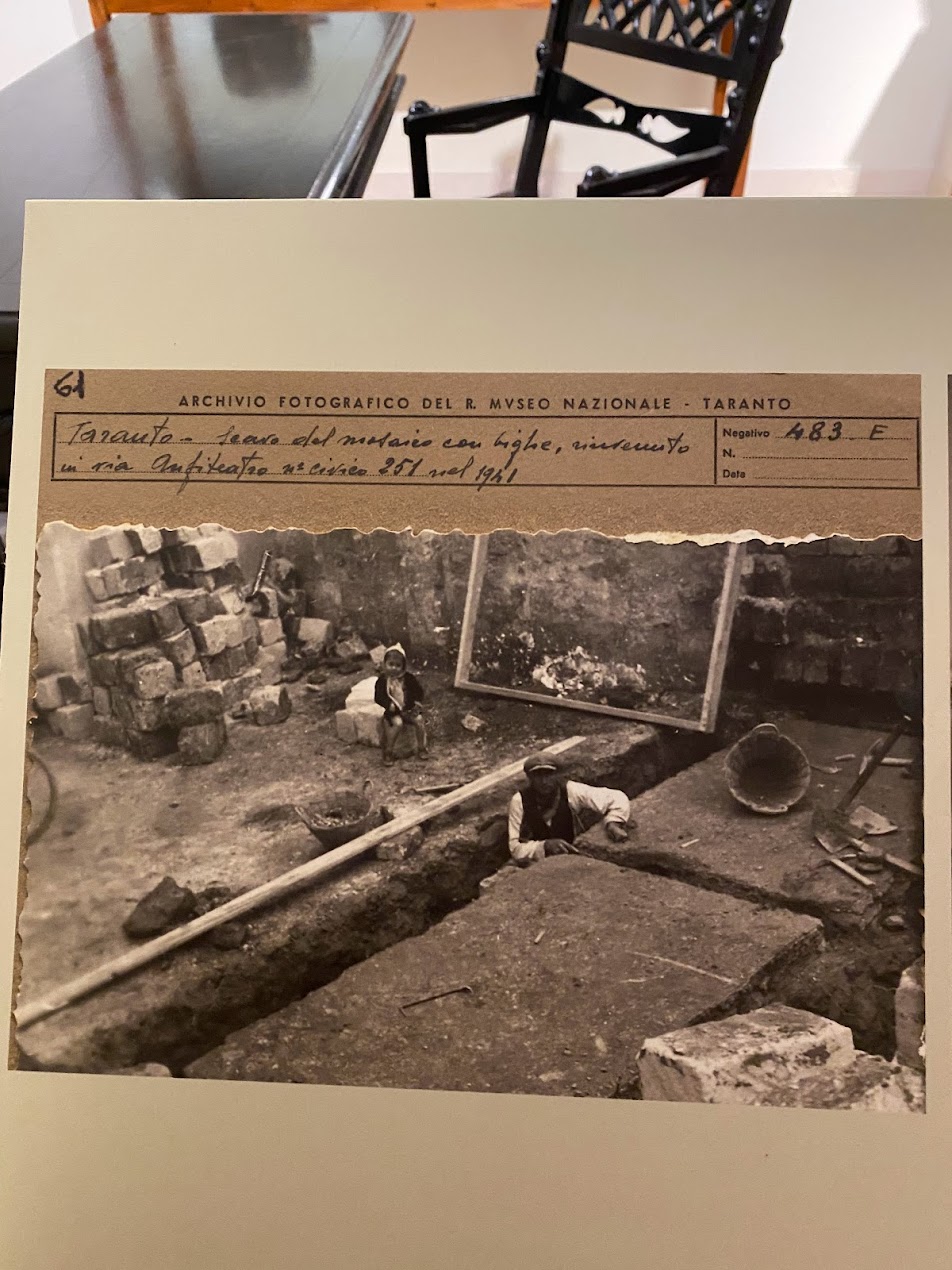

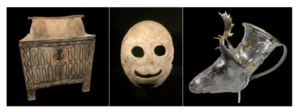

Amongst other treasures in MArTA are beautifully preserved mosaics, ornate golden jewelry, and ancient gold-covered snake skins. Another museum highlight are the informative displays positioning objects in creative contexts. For example, some objects are displayed along with photographic evidence and documentation about their excavation.

Tomb of the Athlete

The museum presents objects in beautiful vitrines. Some of the highlights on the first floor include thematic displays, such as a wall depicting Medusa’s face on antefixes found in Taranto. The curation includes information about the figure of Medusa in mythology and details on how her portrayal evolved over time. Another engaging display involves #italianmuseums4olympics, the Ministry of Culture’s campaign to support Italian sport and culture during the Olympic games. That particular display includes the sarcophagus of an athlete from Taranto, complete with amphorae found in his tomb that include images of athletic competitions, celebrating Italy’s long tradition of participating in the Olympics since antiquity.

An Apulian krater by the Darius painter returned from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2009

Looting of Objects on Display

As visitors enter the next floor of the museum’s route, they are confronted with a large restituted antiquity. A large Apulian krater by the Darius painter was returned to Italy in 2009 from the Cleveland Museum of Art after it was recovered by the Carabinieri’s TPC (the nation’s famed “Art Crime Squad”). The work was among fourteen artifacts returned from the Ohio museum after a two-year negotiation resulting from the investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici and Gianfranco Becchina, two well-known dealers of looted materials who sold antiquities at auction and through dealers to supply coveted objects to collectors and museums around the world.

Loutrophoros restituted by the J. Paul Getty Villa in Malibu in California

MArTA also acknowledges some of the people responsible for the development of its exquisite collection, including past directors and donors. The displays note that the illicit or unknown sale of antiquities has led to the loss of knowledge about their historical and cultural value (when artifacts are illicitly excavated and divorced from their contexts, valuable information is lost in the process). However, the development of patrimony laws has allowed the Italian government to control more of the archaeological discoveries taking place, and other legislation has also encouraged collectors to donate their property to the museum and Italian State. The display also notes the important work by law enforcement and its success in having works repatriated to Italy, as well as its success in confiscating looted artifacts from private owners and collectors during the 20th and 21st centuries in Italy. Part of this display features works returned from major museums abroad, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum in Malibu, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Labels and Information

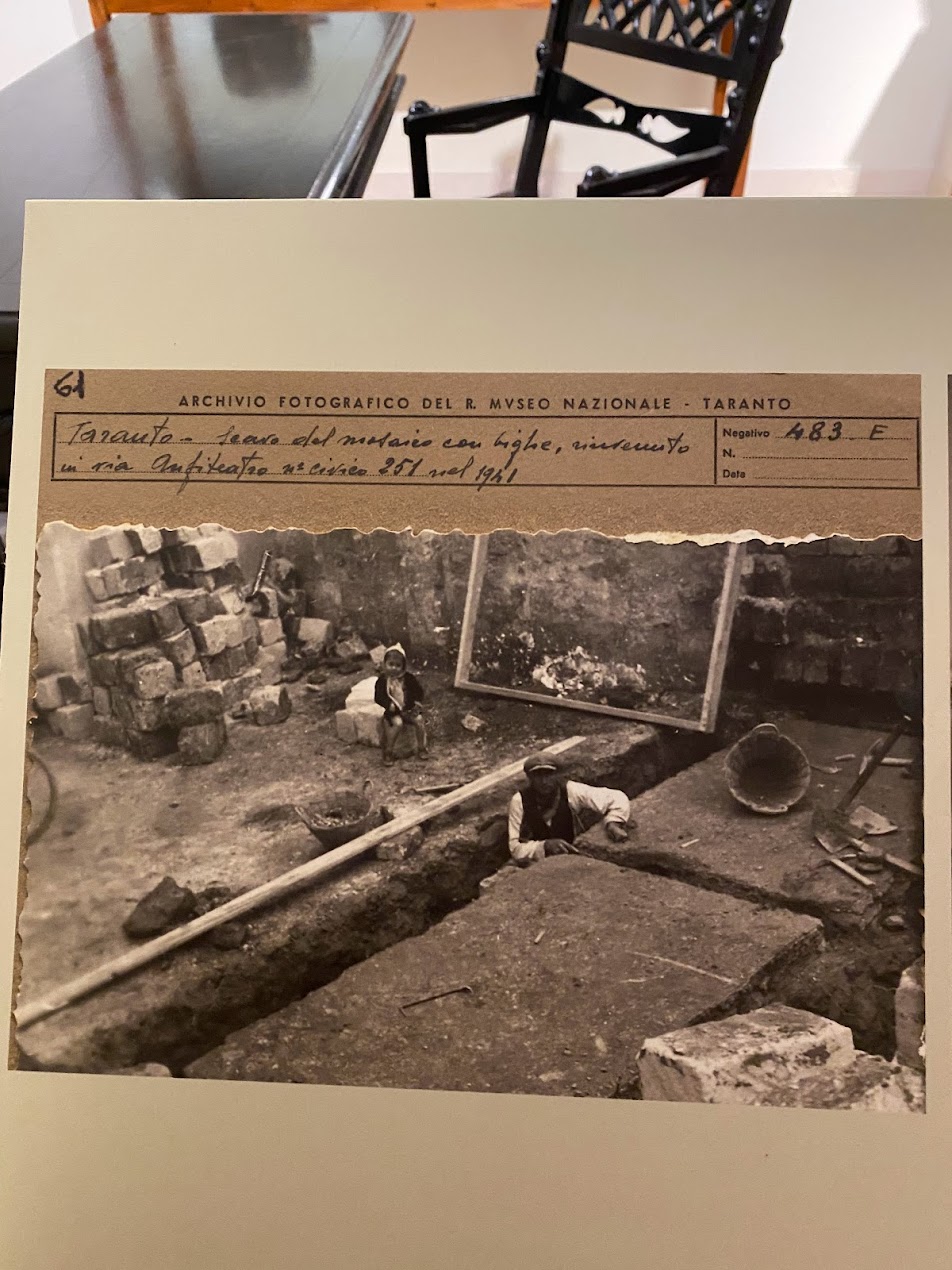

The labels and information offered to visitors at the museum is exceptional, providing valuable information about the historic significance of items on display. Clearly, the museum places great importance on provenance, providing detailed information on where objects were excavated (this information includes exact find spots, with cross streets included for some of the objects), how they entered the museum’s collection, and ways in which the museum has evolved over the decades. Additional information is available to visitors about looting and criminal acts related to the objects, providing useful context.

Copy of the Goddess on Her Throne (the original is in Berlin)

One of the first objects to greet visitors upon their entry is a copy of a goddess on her throne. The original 5th century BC statue is “considered one of the greatest artworks from Magna Graecia.” It was found in 1912 in Taranto, but illegally exported out of Italy. It was then put on the Swiss art market, and finally purchased by the German government. It is currently on display at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Information like this is valuable, because it forces visitors to confront the political, societal, and cultural pressures facing museums, as well as the challenges and realities of the art and antiquities markets. It also provides a practical example of how works can wind up in international museums divorced from their original historical and cultural context.

As the museum’s website states, “The Museum also lends artefacts to other museums to allow global citizens to enjoy. We are aimed at providing first-hand information to all of our visitors so that they understand Europe’s prehistoric period.”

Castello Aragonese

A visit to this museum, and the gorgeous city of Taranto, with its sweeping coastal views, its rich cultural history, and its stunning architectural masterpieces, is essential for anyone visiting Puglia.

Copyrights in all photographs in this post belong to Leila Amineddoleh

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Objects from the museum’s early collection

Documentation of excavations

Vitrine (provenance information for each object is provided in a side panel)

Provenance on view

Beautiful entryways on each floor

Context with a photograph

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 2, 2022 |

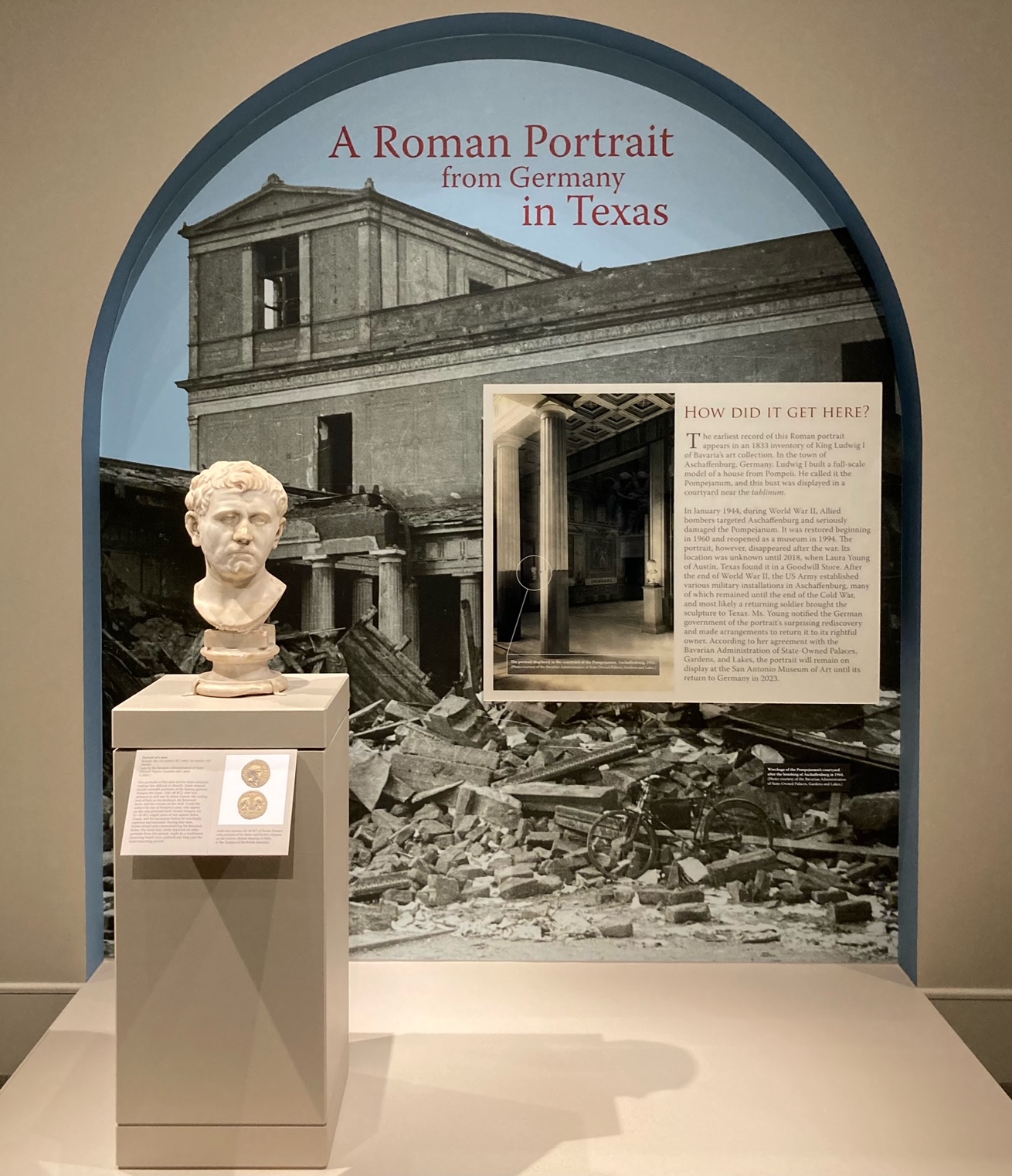

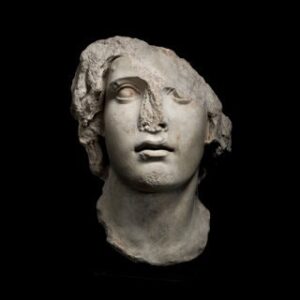

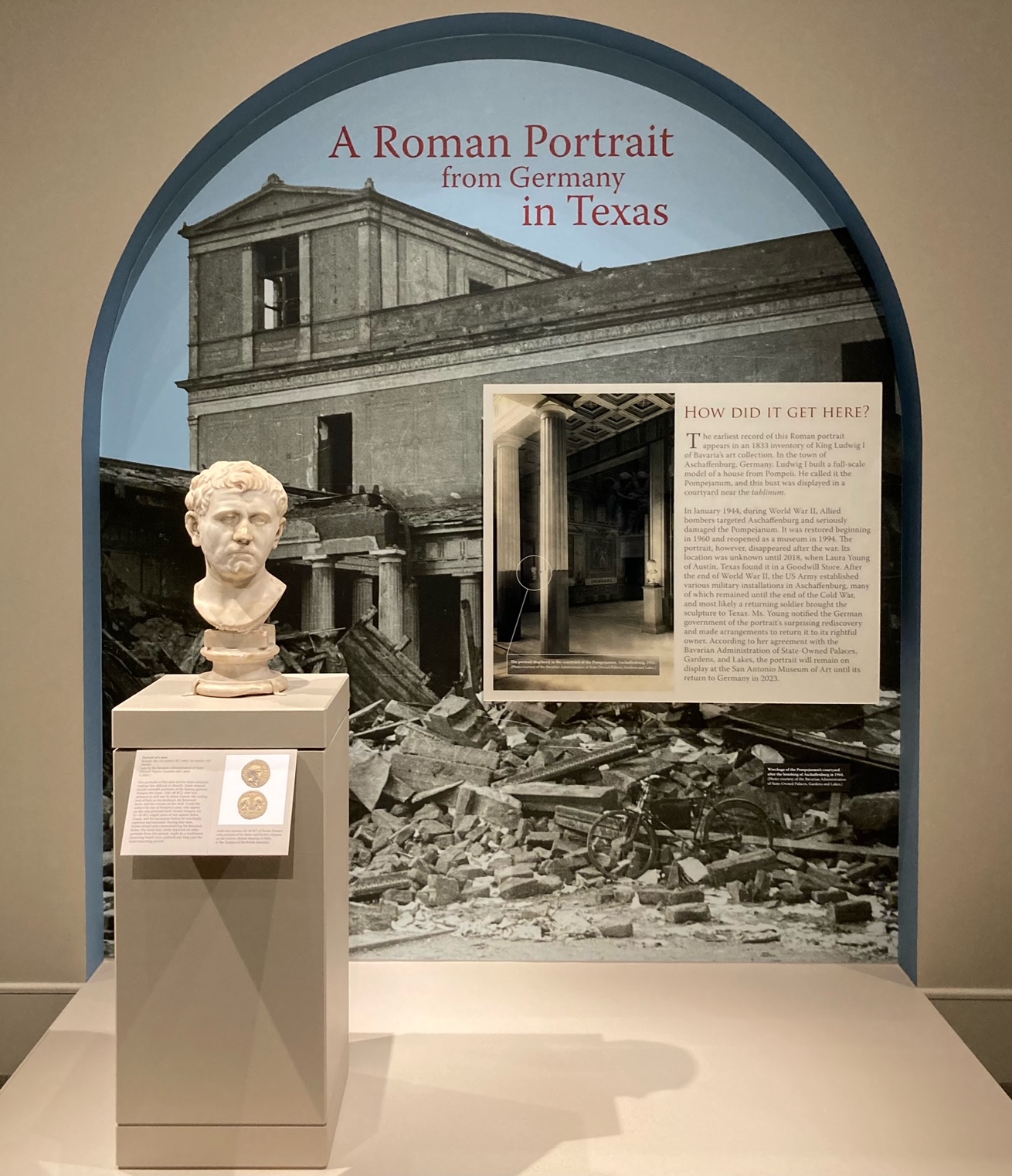

The Marble Bust found in Texas that will be returned to Germany

Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to announce its role in a recent antiquities matter, whereby a Roman marble bust looted during WWII will be restituted to the Bavarian government in Germany. Below, we share details about the bust’s provenance, examples of other cultural objects looted during World War II, the vital work by experts in establishing provenance, and our role in this important cultural return.

I. HISTORY OF THEFT DURING WWII

Much of the literature about WWII-era looted art focuses on thefts perpetrated by the Nazi Party. The Nazis pillaged on a continental scale – appropriating about 20% of all art in Europe at the time. They were notorious for confiscating artworks they deemed “degenerate,” although other works of art were also swept up in their violent mass seizures. One example is the extensive Czartoryski family collection from Poland, which included Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci (later recovered) and a portrait of a young man by Raphael (still missing). After the occupation of Paris in 1940, over 20,000 looted works were taken to the Jeu de Paume gallery, and were kept in a place known as “The Room of the Martyrs.” While Hitler and high-ranking officials had first pick of the loot, German officers could later select masterpieces of their choice. The remainder were slated for destruction, but some evaded this fate thanks to the efforts of art historians and the famed Monuments Men (this title is a misnomer, as this group of British and American members included women).

Looting is often a crime of opportunity, and soldiers on all sides of a conflict may take advantage of the situation by partaking in the appropriation of stolen valuables. Allied soldiers during WWII were no exception. Some of the goods pilfered by Allied troops, like cigarettes and household goods, are relatively inexpensive or nearly worthless by today’s standards. But others – including paintings, rare coins, historic photos, musical instruments, and antiquities – possess great artistic and cultural value. Those valuables continue to be found to this day, sometimes in surprising locations. Some have been returned to the heirs of the original owners while others are involved in ongoing litigation.

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer

In one instance, a member of the U.S. Army stole a collection of medieval religious objects that had been hidden in a cave for safekeeping during the war. The soldier mailed these priceless artifacts home to his family in Texas. These items, known as the Quedlinburg Treasure, included a jeweled 9th-century manuscript written entirely in gold (the Samuhel Gospel). Decades later, the soldier’s heirs reached an agreement with Germany and returned the items in exchange for $2.75 million. Another case involved a pair of portraits by Albrecht Dürer stolen from a museum in East Germany during the war. These were taken by an American serviceman and later bought by a New York collector, Edward Elicofon, for $450. Although Elicofon was purportedly unaware of the paintings’ provenance, a friend recognized the works from a book on art stolen during WWII. After the museum filed a lawsuit in New York, the court compelled Elicofon to transfer ownership and possession of the works back to Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar (Weimar Art Collection).

Perhaps the best-known case involves Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as the Woman in Gold. This gilded painting was forcibly seized by the Nazis after the owners, a Jewish family, were forced to flee Austria in fear of their lives. The portrait is called “the Mona Lisa of Austria.” Along with other works from the Bloch-Bauer’s collection, the portrait wound up in the Austrian State Gallery, but the heirs to the estate fought to recover their family’s lost property. Eventually, after litigation in the U.S. and arbitration in Austria, the Bloch-Bauer heirs succeeded. The dramatic tale became the subject of a film starring Helen Mirren as the main claimant, Maria Altmann, and the painting was later sold in 2006 for $135 million – a record price at the time.

II. AN ART LOVER DISCOVERS THE MARBLE BUST

Not all art and heritage restitutions involve contentious battles. The most recent example of a voluntary return of valuable WWII-looted art can be found in the just-announced agreement between Germany and our client, Laura Young.

The Marble Bust safely strapped in Ms. Young’s car with a seatbelt

Ms. Young happened upon the Marble Bust in the unlikeliest of places: a goodwill thrift shop near her home in Austin, Texas. She purchased the artifact and immediately realized it was more than it appeared to be. The 52-pound Marble Bust, standing at 19 inches tall, was in fact an extremely valuable antiquity. After she drove the Marble Bust home (responsibly strapped into her car with a seatbelt), Ms. Young began digging into its past and discovered the remarkable nature of her find.

Ms. Young later confirmed that, unbeknownst to the goodwill thrift shop owner, the Marble Bust depicts famed Roman commander Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, known simply as Drusus Germanicus or Drusus the Elder. She went on to discover that the Marble Bust has a significant provenance, including links to royalty.

The Marble Bust’s Provenance

- A Roman Marble Portrait Head of Drusus Germanicus (early 1st century AD)

- Acquired by King Ludwig I of Bavaria (before 1833)

- Exhibited in the Pompejanum, Aschaffenburg, Germany (presumably by 1848)

- Stolen during WWII (1944 or 1945)

- Consigned to a goodwill shop in Austin, Texas (Unknown date)

- Purchased by Laura Young (2018)

- Title transferred to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes) (2021)

- Loan to the San Antonio Museum of Art (2022-2023)

A Bit of Roman History

To truly appreciate the richness of the Marble Bust’s provenance, a bit of history is required.

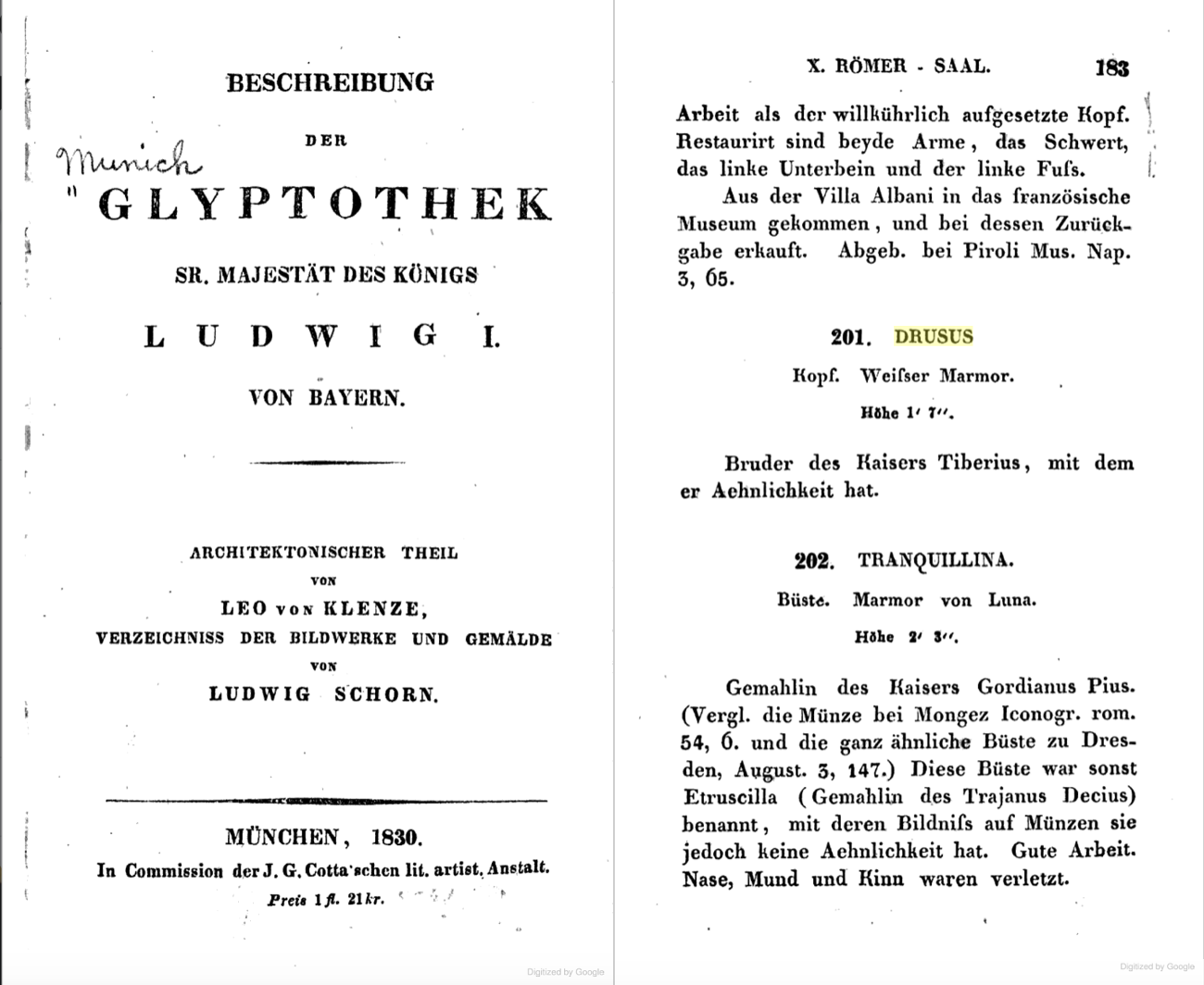

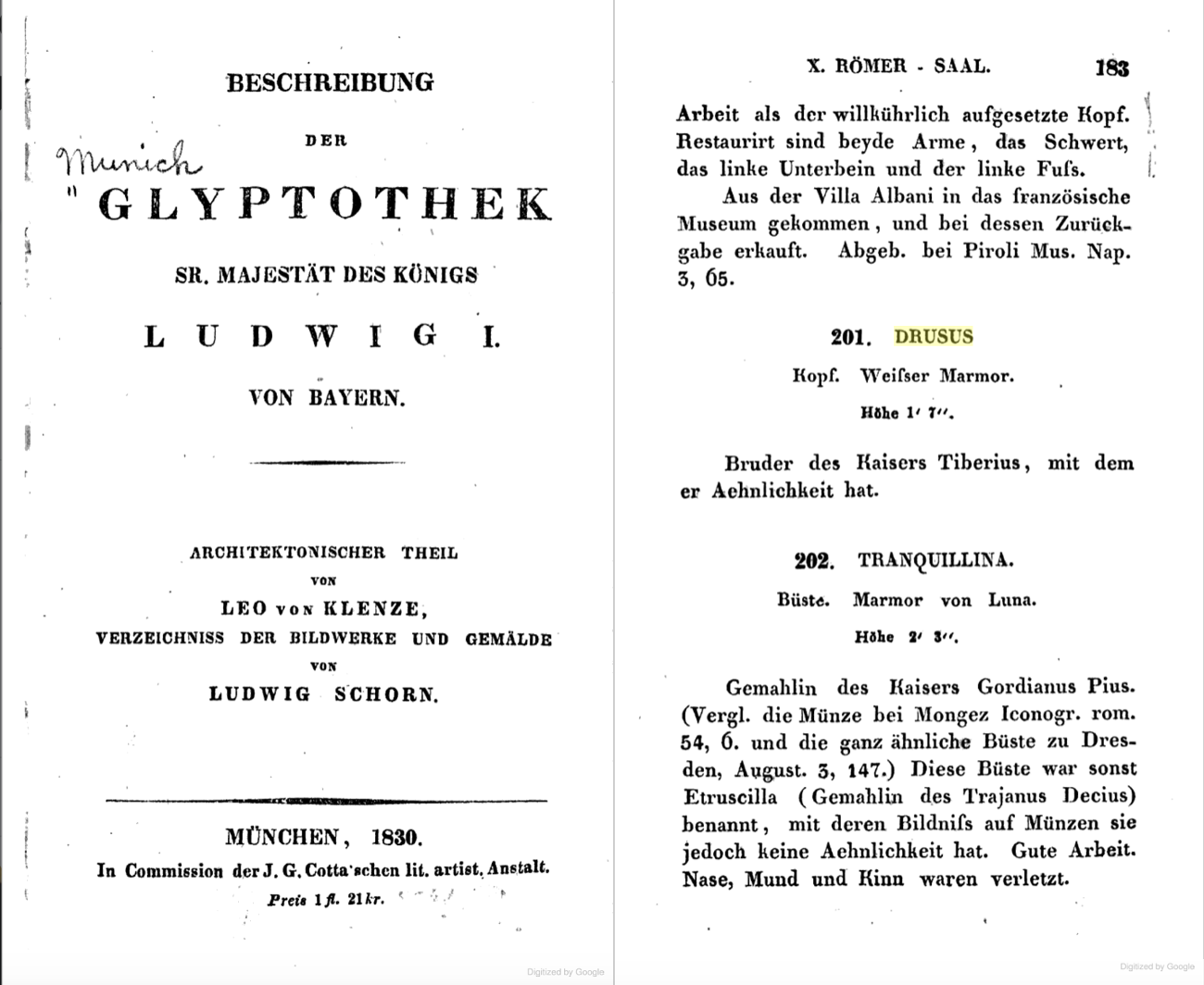

Left, cover of 1833 catalog of King Ludwig I’s antiquities collection , right, description of Drusus (the Marble Head) listed in the catalog

Image from google books digitized version of the catalog

Born on January 14, 38 B.C. to Livia Drusilla and Tiberius Claudius Nero, Drusus Germanicus was the legal stepson of Livia’s second husband, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus and great-nephew of Julius Caesar). Drusus was born shortly after his mother’s divorce, and his mother immediately married Octavian, who historians suspect was Drusus’ true father. Drusus Germanicus eventually became the commander of the Roman forces occupying the German territory between the Rhine and Elbe Rivers. In 9 B.C., Drusus reached the Elbe River, but he was thrown from his horse and died 30 days later from the injuries he sustained. For his conquest of Germania, he received the posthumous honorific title “Germanicus.” The Marble Bust of Drusus Germanicus traveled to Germany nearly two millennia later after its acquisition by the King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, at some point prior to 1833.

Although Drusus was lesser known than some other members of his family, portrait heads of this figure are rare (perhaps due to Drusus’ early death) and highly prized.

Ludwig I and the Pompejanum

After its acquisition by Ludwig I, the Marble Bust was transferred to a most fitting location – the Pompejanum. The Pompejanum (or Pompeiianum) is a replica of a Roman townhouse in Pompeii. Overlooking the Main River in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg, the museum was already a popular tourist destination in the 19th century. The Pompejanum was commissioned by Ludwig I, who was inspired, like many cultural enthusiasts, by the excavations at Pompeii.

Ludwig I was both an art lover and a great patron of the arts. During his reign from 1825 through 1848, he commissioned major museums and art projects throughout Bavaria and the rest of Germany in a bid to elevate Munich to the status of rival European art capitals, like Rome and Paris.

His passion for art was first awakened on a trip to Italy from 1804 to 1805. After that trip, the future king became a voracious collector. Much like today’s collectors, he sent agents across Europe to acquire masterpieces. (One of his art dealers, Johann Martin von Wagner, was noted for his unerring eye, scholarly talent, and great commercial aptitude.) With an unlimited amount of money to draw on from his royal coffers, Ludwig I scooped up many highly sought-after pieces. To display his massive collection, Ludwig I commissioned the construction of a number of major museums. One of his first projects was the Glyptothek, which was used to house ancient sculptures. Another, the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities), was designed in 1848. The works from that institution formed part of the extensive collection of the Bavarian Royal Family.

Ludwig I’s taste in art also ventured beyond the ancient world. In 1836, he created the Alte Pinakothek, the largest museum in the world at the time of its inauguration. Ahead of his time, Ludwig I also established one of the first contemporary art museums in the world–which was unfortunately destroyed by bombing during WWII.

Ludwig I had a deep appreciation for ancient masterpieces and structures evoking the classical era. Projects inspired by this passion include the Propylaea, a monumental city gate constructed as a copy of the Athenian Acropolis and ultimately dedicated as a memorial for Ludwig I’s son Otto, who ascended to the throne of Greece in 1832. It was financed by Ludwig I’s private resources after his abdication, and serves as a symbol of friendship between Greece and Bavaria. While he was still a young crown prince, Ludwig I conceived the project of Walhalla, a temple erected to honor famous Germans. This hall of fame honors nearly 200 laudable people spanning 2,000 years of German history, including both male and female politicians, sovereigns, scientists, and artists, from Albrecht Dürer to Sophie Scholl. Although it is named after the Norse mythological heaven for warriors, the temple was built in the Greek Revival Style and modeled after the Parthenon. The temple continues to be used today, and 19 busts, including one of Albert Einstein, have been added to the collection since WWII.

Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Germany, as restored today

© Carole Raddato (owner of Following Hadrian)

Ludwig I also aspired to bring a bit of ancient Rome to Bavaria. As such, he commissioned the Pompejanum, mentioned above, which was constructed between 1840-1848. Designed by architect Friedrich von Gärtner, it was loosely modeled on the House of the Diosuri (Casa dei Dioscuri) in Pompeii. The villa was never intended to be used as a residence; rather, it has always served as a museum. Located near Schloss Johannisburg (one of Ludwig I’s residences), the king could admire it from his window and make frequent visits. Completed with a Mediterranean-style garden and filled with reproductions of mosaics, architectural forms, and artifacts, the king could escape to Italy with just a short trip to the Pompejanum.

Visitors came to the Pompejanum because it was, and perhaps still is, the most accurate reconstruction of a Roman villa in the world. The ground floor features an entrance hall, the guest room, the kitchen, the dining room, and atrium, all organized around two courtyards. The interiors were painted in the Pompeiian fresco style, and the floors feature copies or adaptations of ancient works and Roman mosaics. The collection included Roman marble sculptures, bronze statuettes and glasses, and household items, as well as two god’s thrones made of marble.

Destruction of the Pompejanum

The Pompejanum destroyed after WWII bombings

Sadly, as often happens during conflict, the damage to the museum’s physical structure led to the loss of its collection. The Pompejanum and the surrounding areas were heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1944 and 1945. Some of the museum’s objects survived bombing only to be looted. But nothing looted from the museum was ever sold by the museum or German government, and thus title to any looted property remained with the Bavarian State. Under U.S. common law principles, valid title to artwork cannot be transferred through looting. There must be a legitimate transaction for title to vest legally in a subsequent purchaser. This means that the Bavarian State continues to maintain a legal claim of ownership over objects that were taken from the Pompejanum.

The Pompejanum Today

The Pompejanum was eventually restored during several phases, the first beginning in 1960. The restoration was completed in 1994, and the villa reopened to visitors that year as the museum of the Bavarian Palace Department and the State Antiquities Collections. Today, it is open to visitors from the spring through the fall.

III. AN ART EXPERT ILLUMINATES THE MARBLE BUST’S PROVENANCE

Establishing the provenance of artwork and antiquities is essential, particularly for objects displaced during times of conflict. It is important not to underestimate the role of art experts in determining provenance, as well as the return and restitution of looted objects. Due to their specialized knowledge and access to resources that are not necessarily available to the public, art experts play a crucial role in establishing the provenance of works and alerting owners to potential red flags. It is always important for purchasers of artwork with unclear provenance or gaps in the chain of ownership to consult experts and ensure that title has been properly transferred.

This pre-war-photo shows the Bust, together with another (today in the Antikensammlungen), standing in the Atrium at the entrance of the Tablinum.

To research her new-found treasure, Ms. Young contacted Sotheby’s. The auction house’s consultant researcher in Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, Jörg Deterling, identified the subject of the Marble Bust as Drusus Germanicus and alerted Ms. Young that the work had gone missing from the Pompejanum decades ago. Before being looted, the Marble Bust had been displayed in the Atrium, at the entrance of the Tablinum that led to the Pompejanum. Although the exact path of the Marble Bust from Bavaria to Texas is unknown, it is safe to assume that it was looted either by an American serviceman who brought it back to the U.S. or by someone who eventually sold it to an American, likely during WWII or immediately after the end of the conflict.

According to Sotheby’s, Mr. Deterling has been “responsible for many returns, restitutions, and repatriations over the years, but his name has never appeared anywhere in connection with them.” Here, he once again played an instrumental role in the return of a valuable artwork by informing Ms. Young about the historical significance and provenance of her find.

IV. AMINEDDOLEH & ASSOCIATES HELPS MS. YOUNG RESTITUTE THE MARBLE BUST TO GERMANY

Drusus Germanicus on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art

After being informed of the Marble Bust’s provenance, Ms. Young worked with Amineddoleh & Associates to voluntarily transfer title to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes), a government agency in Bavaria, Germany. As part of the restitution agreement, the Bavarian agency committed to loaning the Marble Bust to the San Antonio Museum of Art where it is expected to remain on view until its scheduled return to Germany in 2023.

Rather than sell the Roman bust on the antiquities market, where she could have made hundreds of thousands of dollars, our client instead chose to act ethically and return the bust to its rightful home. We worked with Ms. Young to communicate with German authorities, negotiate the transfer of title, ensure proper acknowledgement of Ms. Young’s actions, and request the work’s temporary display in Texas where its story and our client’s role could be further relayed. The Marble Bust’s journey is an extremely important story to tell. It reflects our passion for the past and collecting, the value of museums in providing access to heritage and knowledge, the unfortunate displacement and destruction of national and cultural heritage during conflict, and the hope that people and institutions will choose to act ethically and protect our shared heritage.

In fact, earlier this week the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced the return of a looted marble sculpture to Italy. As in the case with Drusus Germanicus, the object was likely stolen during WWII. The MFA had purchased the antiquity from a Swiss dealer in 1961 for $750. Other records of its whereabouts prior to the purchase are lost, but the dealer had represented that the object originated from Rome. Unfortunately, the MFA’s sculpture had suffered significant damage, such as the loss of facial features, including its nose, mouth and lower left cheek. The Boston museum worked with the Italian Ministry of Culture to effectuate the return of the looted antiquity.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to represent clients who value cultural heritage and consult us in matters involving provenance, authentication, ownership, and restitution. In doing so, they help ensure that cultural heritage is protected and safeguarded for current and future generations while being shared with as many people as possible. Thank you to The Art Newspaper for sharing details about this story HERE.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 18, 2022 |

Authenticating artwork can be a complex endeavor at the best of times. Because the value of artwork – both aesthetic and monetary – is subjective, it relies on a complex process involving authentication. In layman’s terms, authentication is ascertaining whether a work is original and can be attributed to a certain artist. However, when an authentication is questioned, this inevitably leads to disputes. There is no shortage of cases involving inauthentic artworks created by forgers (such as Wolfgang Beltracchi and Pei Shen Qian in the infamous Knoedler Gallery scandal), but a rather unique situation arises when artists themselves disavow their work. Can it still be considered authentic in such circumstances? Who is the rightful person to determine the authorship of a work – the themselves, a seller, a buyer, or an expert?

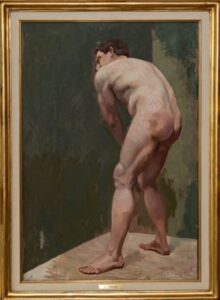

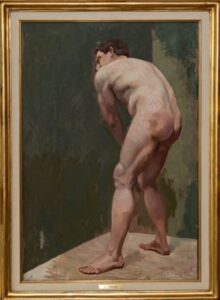

Standing Male Nude, by Lucian Freud

Photograph Courtesy of Thierry Navarro

Lucian Freud’s Standing Male Nude – A Case Study in Authentication and Disavowal

In the case of Lucian Freud, one of the leading English artists of the 20th century, his own denial of a painting was not considered conclusive enough to classify the work as inauthentic. In the mid 1990s, the painting, Standing Male Nude, was purchased by a Swiss art collector. The collector recalls that a few days later, he was contacted by Freud who wanted to repurchase Standing Male Nude, offering him double what he had paid. Upon the collector’s rejection of this offer, the artist became furious and said that unless the collector sold him the work, he would deny having painted it and leave the collector unable to sell. The Freud estate subsequently refused to authenticate the painting, and the collector’s piece languished in limbo for decades.

However, this past November, a team of art experts found definitive evidence confirming what the artist had denied: the painting was, in fact, an original Freud. Scientific tests involved taking pigment samples and using infrared imaging to compare Standing Male Nude with other authentic works by the artist. The work was found to have “an absence of negative indicators for [Freud’s] authorship” by a leading British expert, Dr. Nicholas Eastaugh. These findings were supported by groundbreaking AI technology used by Dr. Carina Popovici at Swiss company Art Recognition. As a result of their own research into the work’s provenance, the collector and private investigator Thierry Navarro believe that the painting was a self-portrait and that Freud was embarrassed by the nude of himself. Although the figure in the portrait is viewed from behind, the facial features appear to match photographs of Freud. Prior to the collector’s acquisition, the painting had hung in a Geneva flat used by fellow artist Francis Bacon at a time when the city served as a “bubble” for the gay community. This helps explain why Freud was so intent on recovering the work.

By creating an authenticity question, the painting’s marketability and resale value was sharply limited. Only works with certificates of authenticity or similar guarantees by living artists will fetch high prices on the legitimate market. Freud’s paintings are worth millions – a lifesize nude of his muse Sue Tilley sold in 2015 for £35.8 million at Christie’s. Previously, another portrait of Sue sold in 2008 for $33.6 million, setting a record at the time for any living artist.

Essentially, authentication can “make or break” the worth of a painting because its attribution is critical. As more and more people view art as an investment and separate asset class, authenticity goes to the core of how the art market operates. But this is not a new phenomenon.

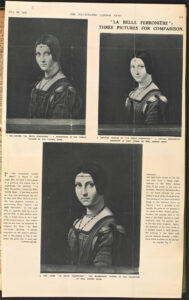

Hahn v. Duveen: The Authentication Case that Rocked the Art World

In 1920, legal disputes concerning art gained worldwide attention when the owner of a painting, believed to be by Leonardo Da Vinci, sued an art dealer who questioned the authenticity of the subject artwork. Dealer Joseph Duveen was one of the world’s best known and successful dealers. Although Duveen had never seen the painting or examined it in person before rendering his opinion, he reasoned that the painting in dispute could not be authentic because the genuine version of the work was in the Louvre. His statement made the painting worthless and unsellable due to the dealer’s sway over other collectors. This case, Hahn v. Duveen, was described as “the world’s most celebrated case of art litigation – a hearsay case with a picture as defendant.” In particular, Duveen was sued for libel; a legal claim that requires the substance of a statement to be false and made with malice.

Clipping from The Illustrated London News of La Belle Ferronière, July 18, 1931 from a Duveen Brothers scrapbook

The court’s opinion criticized the art market and the authentication process: “[a]n expert is no better than his knowledge. His opinion is taken or rejected because he knows or does not know more than one who has not studied a particular subject. . . . Because a man claims to be an expert, that does not make him one.” Hahn v. Duveen, 234 N.Y.S. 185, 190 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1929). Nonetheless, the hold of connoisseurs like Duveen is not so easily dispelled. The market relies heavily on subjectivity when assigning value to works. What makes one artist more valuable than another is not a straightforward matter, and courts in New York (the heart of the global art market) have consistently declined to regulate how the market operates, arguing that it is a matter for participants and experts to decide, as they have the required specialized knowledge. Whether this “hands off” approach is appropriate or not is a question for another day, but it is worth noting that the parties in Hahn v. Duveen settled out of court without a firm attribution in place. Decades later though, Duveen was vindicated when the work sold as a “copy” for $1.5 million in 2011 (likely due to the work’s fame as a result of the litigation).

The situation becomes even more complicated when the person refuting the authenticity of a work is the artist, and not merely someone who “studied a particular work.” How does authentication come into play at such a time?

Authentication as a Three-Legged Stool

In the art market, authentication is often compared to a three-legged stool, which relies on three prongs: forensics, provenance, and connoisseurship. (1) Forensics relies on ever-developing technology to run a myriad of scientific tests on the work. These tests determine certain physical attributes of the painting that can lead to a conclusion supporting its authenticity. However, forgers are also aware of the tests that are run on these works and are able to avoid detection by employing creative methods, such as artificially aging works or using the same pigments as the original artists. (2) Provenance looks at historical evidence tracing the ownership of the work. Ideally, the history of the work can be traced back to the artist without any gaps. (3) The final prong relies on connoisseurs who use their expertise and judgment to determine whether they believe that a work is authentic. This type of evaluation, also known as stylistic analysis, relies on the expert’s “eye” to recognize the artist’s unique style, including the subject matter, brushwork, choice of colors, and composition.

Authentication is established by balancing these three prongs. However, courts, as compared to the art market, tend to weigh these prongs differently. Court prefers the more concrete prongs of forensics and provenance research, whereas the market tends to rely upon connoisseurship. This may cause tension as a court can determine that a work is authentic by weighing the persuasiveness of expert credentials and testimony, but this will not necessarily be reflected in the market. In Greenberg Gallery, Inc. v. Bauman, 817 F.Supp. 167 (D.D.C. 1993), the court sided with plaintiff’s expert Linda Silverman in holding that a mobile sculpture, titled Rio Nero, was an authentic work by Calder, even though Klaus Perls, a renowned Calder expert, identified it as a copy. The court noted that as a trier of fact, it relied on a preponderance of the evidence. However, the art market operates in a very different manner and Perls’ opinion was seen as definitive. The mobile remained unsold for years.

A Lack of Definitive Answers: The Pollock Dilemma

Given that none of these three prongs provide conclusive results, each analysis may lead to contradicting conclusions. As a result,

Jackson Pollock painting. in his studio

Photo by Martha Holmes/The LIFE Premium Collection/Getty Images

many experts may disagree on the attribution of a work. For example, in 2013, the three prongs left the authenticity of a Jackson Pollock unclear. The work in question, a painting titled Red, Black & Silver, was allegedly created by Pollock for his lover Ruth Kligman. The artist’s widow, Lee Krasner, and the Pollock-Krasner Authentication Board disputed the claim. After Kligman’s death, her estate attempted to sell the work at auction in 2012, but it was withdrawn by Phillips so that further research could be performed.

The forensic evidence suggested that the work was done by Pollock. Scientific analysis found a polar bear hair embedded in the painting, which suggested that the painting was authentic since Pollock had a polar bear rug in his studio in 1956, and he was known to lay the paintings on the floor. But the provenance was less cer

tain. While a clear chain of ownership was identified, there was no historical documentation to verify this claim. Lastly, connoisseur Francis V. O’Connor stated that the work does not look like a Pollock. He opines that even if the work was made on Pollock’s estate, it wasn’t necessarily by Pollock’s hand. In this case, as in many others, the three prongs of the ‘three-legged stool’ analysis have resulted in an inconclusive determination as to the authenticity of a work. As a result, this work remains in limbo.

Protecting Expert Opinions: A Legal or Market Concern?

The lack of certainty in the authentication process has led many art experts to hesitate when offering opinions about authenticity. In many instances, art experts have provided their opinions, and their opinions have subsequently been proven wrong. When an art owner is harmed by the opinion of an expert, that owner may decide to sue. This has led many art experts to be hesitant to provide their opinions for fear of facing litigation. As a result, there are fewer connoisseurs providing opinions, thus resulting in a decline in the quality of connoisseurship.

Legal actions taken against authentication boards and experts affect the art market. In Thorne v. Alexander & Louise Calder Foundation, 70 A.D.3d 88 (1st Dept. 2009), the plaintiff sued the Calder Foundation because it declined to authenticate two theatrical stage sets and related materials designed by the artist. The court found that there was no legal basis to compel the foundation to issue an authenticity opinion, even though it would impact the sale price. The Andy Warhol Foundation has also faced its share of lawsuits, with Simon Wheelan v. The Andy Warhol Foundation, 2009 WL 1457177 (SDNY 2009) alleging that the foundation strategically refused to authenticate certain works to drive up the value of others and monopolize the market. While this case was ultimately withdrawn, it calls into question how experts are regulated to ensure good faith when issuing opinions.

Experts can face liability for incorrect opinions, even those given in good faith, under the theory of tort negligence, in addition to legal costs associated with defending themselves. A flurry of lawsuits culminated with Keith Haring Foundation disbanding its Authentication Committee in 2012. As a result, authenticators are not providing opinions, which is negatively affecting the art market. In response, a bill was introduced in the New York State Legislature in the spring of 2014. This bill, which would amend the New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, would protect art authenticators from “frivo

lous or malicious suits brought by art owners.” Authenticators are defined as individuals and entities “recognized in the visual arts community as having expertise regarding the artist” when rendering an opinion. A modified version of the bill was passed in 2015, but it remains to be seen whether this will provide a robust shield for art experts issuing authenticity opinions.

Moral Rights Legislation – a Shield or a Sword for Artists?

In many instances, artists are victims of the art market’s subjectivity when determining authenticity. For example, in Herstand Co. v. Gallery, 211 A.D.2d 77, (N.Y. App. Div. 1995), Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, a Polish-French modern artist known as Balthus, declared and signed that a drawing was not authentic. Despite Balthus’ confirmation, the court ruled in favor of the gallery selling the artwork, choosing to believe an expert’s testimony of authenticity over the artist’s own actions.

However, visual artists possess legal rights that can protect them and their works. Most countries have a moral rights system allowing an artist to protect their personal and reputational rights, in addition to their economic rights (such as copyright). For example, many countries grant artists the right to not have a work falsely attributed to them and to protect their honor and reputation with respect to their works.

In the United States, some of these rights have been codified in the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA). VARA is more limited than international art law, or the moral rights of other countries, such as France. Under VARA, an artist’s rights are limited to their lifetime and cannot be assigned or transferred. But VARA grants artists two overarching rights with respect to their authorship. First, artists have a right of attribution, so that an artist is recognized for works they create and are not associated with those that they did not create. Second, artists have a right of integrity to protect their reputation, such that they can disavow works that have been damaged, altered, or mutilated.

However, as seen in the case of Freud’s rejection of Standing Male Nude, artists can also create uncertainty and manipulate the authentication of their works for their own personal reasons.

Cowboys Milking, 1990, Cady Noland

Another artist, Cady Noland, disowned her work, rather than rejecting it outright. This occurred with two different works that were damaged or not properly stored and preserved. Her 1990 silkscreen on aluminum, Cowboys Milking, went up for auction at Sotheby’s but upon Noland’s inspection, she noticed that the corners of the aluminum were damaged. Similarly, Janssen Gallery stored Noland’s sculpture, Log Cabin (1990), improperly and the gallery restored the work without Noland’s consent. In each instance, Noland disowned the work, arguing that if the work were to be auctioned off with her name attached, it would prejudice her honor and reputation. Noland’s rejection of two sculptures spurred lawsuits from the owners, who were no longer able to sell the works for their full value.

Elyn Zimmerman, known for her large scale art sculpture installations, also rejected two projects from her list of works. In one instance, the work was not installed consistent with her design, and the contractor left a large hole in the sculpture. Zimmerman said that the work was past salvaging, and so decided not to put her name on the piece. Both Zimmerman and Noland exemplify ways in which some artists rely upon their reputational rights to remove any unwanted attributions.

Other artists simply reject any association with works so that they can assert control over their oeuvre.

Richard Prince is well-known today for his appropriations of advertisements and other popular images. However, before he gained acclaim in the 1980s, he had explored a variety of different mediums including paintings, drawings, collages, and etchings. In a 1988 interview with Flash Art magazine, Prince said he destroyed 500 of his early works. Prince said that he ripped up the works that he did not like from the mid to late 1970s and put them in garbage bags. However, several works from that period were already sold and were beyond his reach. Prince has claimed that these works no longer represent him as an artist. Over the years, Prince has taken several steps to disavow his early work and re-create his oeuvre beginning in the 1980s. On Prince’s website, his biography omits any exhibitions of his work before 1980, creating the public impression that his career began in that year. He also relied upon the copyright to his art, refusing any reproductions of these early works to be printed in books or catalogues. When a museum exhibited his early work, he refused to participate or grant the museum any rights for images or reproduction. Generally, major museums have followed Prince’s example; both the Guggenheim and Whitney Museums have only acknowledged and exhibited works from or after 1980 in their retrospectives of Prince.

Gerhard Richter in his studio with his paintings on the wall, February 1962.

Copyright and Photo by: Gerhard Richter 2020 Courtesy of the artist and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

Gerhard Richter, a German artist whose works have sold for record prices, remains in strict control of his catalogue raisonné to this day. Over the years, Richter has become an artist known for revising and editing his oeuvre. He has removed works from catalogues and rejected paintings from his early West German period. During this period, between 1962 and 1968, Richter went through a stylistic evolution in which he experimented with a figurative style. These realistic paintings varied greatly from his later abstract and photo-realist paintings. Richter’s revisions of the historical catalogues has sparked controversy. As the artist and creator of the paintings, he has a right to define his own body of work. Yet, using this right to modify these historical catalogues can create disputes and distrust in their historical accuracy, and rejecting works offhand can manipulate the market and the resale of works disowned by the artist.

Another famous artist, Pablo Picasso, famously said “I often paint fakes.” This statement questions the art market and the authentication of works but also causes problems for buyers. This was also reflected when Picasso rejected a painting later confirmed to be his original work. When he was handed a photograph of Erotic Scene (La Douceur), he said it was not his work, but just a “bad joke by friends”. The painting, gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1982, sat in storage for several decades. In 2010, the Met prepared for a Picasso show and was faced with authenticity issues concerning the work. The museum ultimately confirmed that the painting was authentic despite Picasso’s statement.

Pest Control Logo

Photo from Pest Control website

As the art market has developed and the complexity of authentication leads to legal controversy and disruption, living contemporary artists have taken authentication into their own hands. Banksy has put a system in place that allows him to be the only authority on the authenticity of his work. This control is in part a by-product of his anonymity. In 2008, Banksy established Pest Control to serve as the sole authenticator of his works. Any Banksy sold after 2009 will be accompanied by a certificate of authenticity (COA) issued by Pest Control and they will retroactively issue COAs for any pre-2008 works they deem authentic. Establishing a third-party authenticator like Pest Control protects the artist’s rights, but it can also influence the market. As seen above, the artist does not always have the final say in the authentication of their works. Pest Control, however, has allowed Banksy to do so. In 2008, five works came up for auction at Lyon & Turnbull in London, and Banksy refused to authenticate them. Pest Control rejected the works’ authenticity and encouraged buyers to boycott the sale. As a result, none of the works were sold. Pest Control has given Banksy access to the art market, allowing him to control what is included in his body of work and sell his work without interference from, or reliance upon, the uncertainty of the three authentication prongs.

As exemplified by Noland, Zimmerman, Prince, Richter, and Picasso, artists have moral rights, and some artists exercise them once their art is on the market. Some artists rely on these rights to protect their work and reputation, others use them to subvert the art market, while others simply wish to remove or disassociate themselves from works they feel are inferior or not representative of their artistic vision and image. While the protection of authors’ rights is important, some question whether artists are abusing their power without considering the larger effects on the market. On the other hand, it may be argued that as the creators of artistic works, artists are in the best position to determine what should or should not be included in their body of work. While this may cause consternation for collectors seeking to resell artworks, there may be limited recourse.

Conclusion

Authentication and attribution is a tricky business. Even after centuries of the art market operating in more or less the same way – responding to supply and demand as well as subjective appraisal – there is still no magic formula to establish whether a work is authentic. Forensic and scientific analysis, combined with a work’s provenance, may provide evidence in support of authentication, but in the absence of a clear link to the artist, collectors risk works being called into question at a later date. Even if an artist is alive at the time the work is sold, there is no guarantee that he or she will wish to remain associated with it. This is why artists and collectors, no matter how new or experienced, should consult with reputable legal counsel to be aware of their rights and risks when engaging in art transactions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 19, 2022 |

Like other nations rich in archaeological material, Mexico has suffered a great deal of looting and illegal export of its cultural heritage over the past decades. Despite enacting protective legislation dating back to the late 19th century, cultural heritage objects from Mexico continue to be smuggled out of the country and sold on the open market. These items, many of which hail from pre-Columbian indigenous societies such as the Maya and Aztec, are highly prized by museums and private collectors alike. Stelae (free-standing commemorative monuments erected in front of pyramids or temples and made from limestone), polychrome vessels, jade and gold funerary masks, stone altars, and sculptured figurines are among the many types of objects offered for sale. This is a profitable business worldwide; according to Sotheby’s, its auctions of these items have reached nearly $45 million over the past 15 years. (One of our previous blog posts details the theft of pre-Columbian antiquities worth over $20 million from Mexico’s National Museum of Archaeology on Christmas Day 1985, and how authorities recovered them 3 years later.)

Pre-Colombian Stelea

Photo Credit: National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

In light of these circumstances, Mexico has recently taken several concrete steps to strengthen efforts to track down and recover cultural and historical artifacts. In 2011, the National Institute for Anthropology and History (NIAH) announced the launch of a new unified database for cultural property, which allows for the inscription of cultural goods from anywhere within Mexico. Each item in the database is provided with a unique ID number and accompanying details (such as type, material, dimensions, and provenance), resulting in a publicly accessible and standardized system. This is an invaluable tool that will aid the government in protecting the country’s approximately 2 million movable artifacts.

Mexico has also implemented measures to further protect heritage items already removed from within its borders. In March 2013, the governments of Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Peru contested the sale of pre-Columbian art from the Barbier-Mueller Museum at Sotheby’s Paris. All these countries have similar laws vesting ownership of antiquities in the State; therefore, they alleged that the sale was illegal because the objects were not accompanied by export licenses or sufficient provenance information confirming that the works were removed prior to the passage of the relevant laws. Nonetheless, the sale went ahead as planned. A French diplomat stated that the items did not appear on the Interpol database or ICOM Red List, and as such were not considered looted or stolen. (This statement was made even though pre-Columbian antiquities are underrepresented on both lists.) Ultimately, nearly half of the lots failed to sell, and the total sales proceeds fell far below the pre-sale estimate. Public pressure may have played a role in staving off bidders.

Despite this controversy, auctions of similar items have continued. In September 2019, Mexico and Guatemala jointly denounced the auction of pre-Columbian artifacts at French auction house Drouot. The auction house claimed the sale was “perfectly legitimate” and proceeded to sell 93% of the lots, netting $1.3 million for the sale. In response, the consigner, Alexandre Millon, stated that he was a victim of “opportunistic cultural nationalism.” This stoked further tension among countries of origin and market countries.

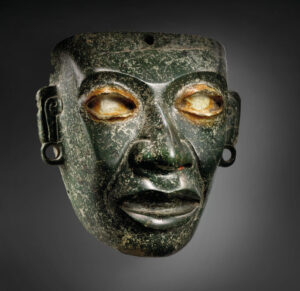

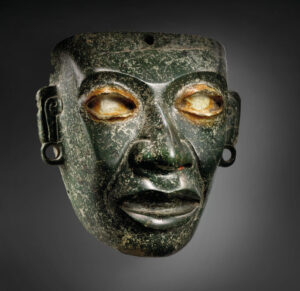

Teotihuacan mask, ca. 450–650

Photo Credit: Christie’s

In February 2021, NIAH lodged a formal legal claim against Christie’s over the sale of 33 pre-Columbian objects, including a stone sculpture of the goddess of fertility Cihuatéotl estimated at $722,000-$1.08 million and a Teotihuacán green stone mask of Quetzalcóatl estimated at $420,000-$662,000. Notably, the mask previously belonged to French dealer Pierre Matisse, son of artist Henri Matisse. While Christie’s maintained that it was confident in the legitimate provenance of the items, historian and archaeologist Daniel Salinas Córdova indicated that the circumstances under which the items had left their places of origin was still unclear. He reiterated that auctioning pre-Columbian antiquities is dangerous because it “promote[s] the commercialization and privatization of cultural heritage, prevent[s] the study, enjoyment, and dissemination of the artifacts, and promote[s] archaeological looting.” Although the sale proceeded and the legal claim has not yet been resolved, Mexico continues to enforce its patrimonial rights.

In September 2021, ambassadors from 8 Latin American Countries (Mexico, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, and Peru) banded together to stop an auction of pre-Columbian artifacts in Germany. Mexican Secretary of Culture Alejandra Faustro sent a letter to the Munich-based dealer, Gerhard Hirsch Nachfolger, citing Mexico’s 1934 patrimony law and reiterating the government’s commitment to recovering its cultural heritage. Mexico’s ambassador to Germany, Francisco Quiroga, even visited the auction house in person in an attempt to block the sale. A complaint was also filed with the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico. The auction took place, but of the 67 pieces identified as being Mexican, only 36 sold. Notably, one of the highlights – an Olmec mask with an estimate of €100,000 – did not achieve the reserve price.

That same month, Mexico announced the creation of a new team composed of National Guard personnel tasked with the recovery of stolen archaeological pieces and historical documents. The nation’s president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, credited Italy with the idea. He stated, “Italy has a special body to recover stolen archaeological pieces. We are going to follow that example, I have given the instruction for the National Guard to constitute a special team for the purpose,” Lopez Obrador said.

As recently as November 2021, the Mexican government issued a letter questioning the legality of two auctions in Paris (at Artcurial and Christie’s) selling pre-Columbian objects. Embassy officials and the Mexican Secretary of Culture asked for the sales to be halted on the grounds that they “stri[p] these invaluable objects of their cultural, historical and symbolic essence, turning them into commodities or curiosities by separating them from the anthropological environment from which they come.” Only a few months earlier (in July), the governments of Mexico and France had signed a Declaration of Intent on the Strengthening of Cooperation against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property, which was meant to signal a recommitment towards the restitution and protection of each nation’s cultural heritage. Although Mexican officials appealed to UNESCO, bidding opened as scheduled on Artcurial’s online platform (with lots priced at $231-$11,600) and Christie’s earned over $3.5 million in its own sale. The day before the Christie’s sale, the embassies of Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru in France issued a joint statement decrying the “commercialization of cultural property” and “the devastation of the history and identity of the peoples that the illicit trade of cultural property entails.”

Nonetheless, Mexico’s persistence has borne fruit. In September 2021, it was able to halt the sale of 17 artifacts at a Rome-based auction house. The Carabinieri TPC seized the objects after an inspection revealed that they had been illegally exported, and returned them to Mexico in October. The successful recovery of these objects demonstrates the importance of international cooperation. Many governments’ resources are stretched thin policing their own borders for cultural heritage smuggling and theft, and therefore greatly benefit from assistance by foreign law enforcement. It is also an example of how successful cultural diplomacy can be in the recovery of such objects.

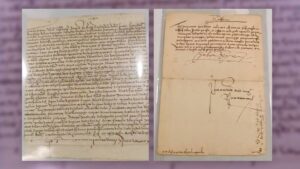

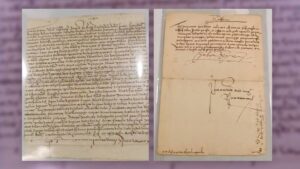

The letter signed by Hernán Cortés recovered by the Mexican authorities.

Photo Credit: The National Archives

In addition to law enforcement and government agencies, laypeople have a crucial part to play in the recovery of looted or illegally exported artifacts. For instance, a group of academics in Mexico and Spain helped thwart the sale of a 500-year-old letter linked to conquistador Hernán Cortés. The letter, dating back to 1521, had been offered for sale by Swann Galleries in New York in September 2021. It was expected to fetch $20,000-$30,000. By searching online catalogues of global auction houses and a personal trove of photographs depicting Spanish colonial documents, the group traced the letter’s provenance to the National Archive of Mexico (NAM), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. An image of the letter had been taken by a Mormon genealogy project, which provided supporting evidence. Furthermore, the group unearthed 9 additional documents linked to Cortés that had been sold at auction – including at Bonhams and Christie’s – between 2017 and 2020. One of these had been sold previously at Swann Galleries for $32,500 and later displayed at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York as part of an exhibition. It was confirmed that all the documents had been stolen from the NAM – they were surgically excised from books – and illegally exported. In response, Swann Galleries cancelled the planned auction. The purchaser of the aforementioned letter returned it in good faith to the auction house. Mexico’s Foreign Ministry enlisted the help of the US Department of Justice to repatriate the 10 manuscripts, in cooperation with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office and Homeland Security Investigations. The manuscripts were formally handed over in September 2021.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Dec 21, 2021 |

In this inaugural newsletter, Amineddoleh & Associates is pleased to share some major developments that took place at the firm during the summer and autumn of 2021.

LITIGATION UPDATES

Ancient marble bust contested in lawsuit

Image from Manhattan DA’s Office

A Victory for Our Client, the Republic of Italy

Amineddoleh and Associates secured a win for its client, the Italian Republic, in the ongoing Safani v. Republic of Italy litigation in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The court dismissed litigation against our client in a case concerning an Italian antiquity seized from a Manhattan art gallery. Read about the litigation update here and the case details here.

(The Plaintiff has since filed a Second Amended Complaint, naming the Manhattan District Attorney as a defendant in the case.)

ART & IP NEWS

Illicit Antiquities Trafficking

In this blog post, our founder Leila Amineddoleh discusses disgraced art dealer Nancy Wiener, who revealed new details about her involvement in the illicit trafficking of antiquities and its effect on the art market in an allocution statement. Wiener had ties to Douglas Latchford, whose recent appearance in the Pandora Papers leak highlights the global nature of the illicit antiquities trade. Read more on our website.

Nazi-Era Looting, Duress Sales, and New Laws

There were a number of developments this autumn concerning Nazi-Era looting. We presented an entry in our popular Provenance Series to examine the issues surrounding the restitution of looted cultural heritage in Poland, including the country’s history, a new law shortening the applicable statute of limitations, and examples of successful returns. Read more on our website. In addition, questions continue to arise concerning alleged duress sales, with one painting in Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts coming under scrutiny. Founder Leila Amineddoleh discussed the case and its implications with media outlets.

Turkey and Antiquities Restitution

Gold ewer

Image from V&A

Firm founder Leila Amineddoleh consulted with the Gilbert Trust at the Victoria & Albert Museum concerning a 4,250 year old golden ewer that was returned to Turkey in October. The ewer was purchased by a private collector who was unaware of the seller’s dirty dealings, including his involvement in antiquities trafficking. Luckily, the Gilbert Trust was proactive and the matter was resolved amicably and creatively. Read about the ewer’s fascinating history and the details of its return here.

NFT Battle: Miramax v. Tarantino

With the ongoing NFT craze, market participants and legal scholars have been waiting for guidance from courts concerning the application of “traditional” intellectual property law to this new digital asset class. We authored a blog post discussing the legal questions and controversies arising as the NFT market continues to grow. NFTs recently made headlines when Miramax sued Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino, the award-winning movie director, announced his plan to sell a new NFT collection consisting of seven tokens to uncut, exclusive scenes from Pulp Fiction. In response, Miramax sued Tarantino for breach of contract, as well as copyright and trademark infringement. Read more about NFTs and this new lawsuit here.

Lifetime Ban on Collecting: the Steinhardt Seizure

Several artifacts seized from Steinhardt

Image from DA’s Office

This blog post details the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office seizure of 180 looted antiquities from Michael Steinhardt. Steinhardt, a hedge-fund pioneer and one of the world’s most prolific collectors of ancient art, was involved in a criminal investigation examining issues with the provenance of various pieces in his collection. The DA’s Office announced that Steinhardt has been sanctioned by placing him under a lifetime ban on the purchase of antiquities. All of the seized antiquities will be returned to their country of origin. Read more about this news on our website. Our founder served as an independent cultural heritage law expert for the seizure of certain items in Steinhardt’s collection. She discussed this with a number of news outlets, including WNYC.

LAW FIRM UPDATES AND EVENTS

New Team Members

Our firm added two new members to its roster this fall: Travis Mock and Deanna Schreiber. Travis is an attorney with a wealth of experience in litigation, IP law and trademarks, while Deanna is 3L at Fordham Law School interested in both transactional and litigation aspects of art and cultural heritage law. Deanna was the winner of the NY State Bar Association’s writing competition for her submission discussing the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act and its future role in Nazi-looted art controversies. We wish Travis and Deanna a warm welcome. Learn more about our team and their accomplishments here.

Art Law Conferences

Congratulations to our firm’s founder Leila Amineddoleh, who successfully chaired the 13th Annual NYCLA Art Law Institute, one of the most anticipated events of the year. Leila also spoke on the topic of foreign sovereign immunity while Associate Claudia Quinones participated in the ever-popular What’s New in Art Law? panel, focusing on title disputes. Check out the conference program and speaker details here.

In early December, Leila and Claudia also spoke at an international conference, The Intentional Destruction of the Cultural Heritage of Mankind, organized by Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza.” They discussed cultural heritage as a human right as well as measures of legal protection in times of peace and conflict. In November, Leila presented a 3-hour lecture on the topic of NFTs for the Executive Master in Art Market Studies at the University of Zurich. Earlier in the month, she presented on “New Obligations in the Art & Antiquities Markets” for the Responsible Art Market Initiative. She also presented a featured lecture, “Cultural Heritage, the Law and Looting,” for the Department of Art History at New York University in October. Before that, she spoke about Nazi Looted Art and the Guelph Treasure for the International Center of Medieval Art.

CLIENTS AND REPRESENTATIVE MATTERS

Leader in the NFT Market

Our firm was hired to create a unique template for the sale and purchase of NFTs on Monax. The company’s cutting-edge digital platform will combine technological expertise with art market considerations to provide users with full support for these emerging digital assets. As NFTs continue to increase in price and popularity, this template has the potential to revolutionize the market. Read more about NFTs and Monax’s services here. A&A also advised Nifty Gateway on its Terms & Conditions, and we have been working with a number of clients on new NFT projects.

Artists, Designers & Fashion

Fragrance of Infinity: Hiroshi Sugimoto’s limited edition perfume bottle

Copyright: Diptyque

In honor of Diptyque’s 60th anniversary, our client Hiroshi Sugimoto collaborated with the fragrance house on a limited edition perfume bottle inspired by the Japanese region of Kankitsuzan. The artist used his childhood memory of seeing the ocean for the first time to create a striking form exploring the relationship between man and nature. More information on the collection can be found here.

Public Art Commissions

In honor of Veterans Day, the People’s Picture (our client) was commissioned by America250 to create a digital photo mosaic depicting African American WWI hero Sgt. Henry Johnson for its November Salute 2021. The stunning mosaic, containing hundreds of photographs of veterans and other military personnel, is accessible online here and you can read more about The People’s Picture and their work here.

Artists, Art Dealers & Art Fairs

A number of our artist-clients received recognition for international art exhibitions over the past year, including the talented Kamrooz Aram. In addition, our collector-clients and dealer-clients were also actively buying and selling art through both online platforms and in-person art fairs.

Television & Film

As television viewership numbers increase during the pandemic, it is a pleasure to work with producers, writers, and on-screen talent creating exciting programs. One of these clients is Terra Incognita, a company producing content for educational, travel, and documentary programming. They focus on high-quality and thought-provoking ideas to empower audiences around the world.

On behalf of Amineddoleh & Associates, we wish you a happy holiday season and wonderful new year.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).