by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 29, 2021 |

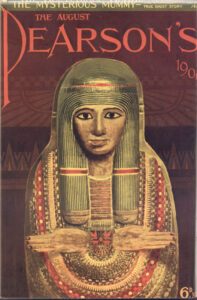

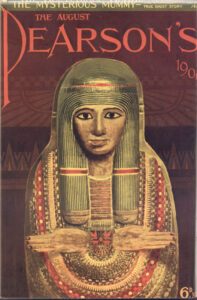

Cover of 1909 Pearson’s Magazine featuring the Unlucky Mummy

Just in time for Halloween, this spooky entry in our Provenance Series explores the strange case of the “Unlucky Mummy,” an ancient Egyptian artifact held by the British Museum since 1889 and rumored to have played a part in several tragic events during the last 150 years. The name of the object is misleading, as it is not an actual mummy, but rather a painted wooden “mummy board” or inner coffin lid depicting a woman of high rank. Mummy boards were placed on top of mummies, covered in plaster, and decorated elaborately with protective symbols of rebirth. The Unlucky Mummy was discovered in Thebes, an ancient hub for religious activity and the site of a renowned necropolis. It dates back to 950-900 B.C.E. While the lid does contain hieroglyphic inscriptions, these only refer to religious phrases; the identity of the deceased remains unknown. In the early 1900s, British Museum specialists believed that she may have been a temple priestess or a member of the royal family, but this was never confirmed by supporting evidence.

According to the museum’s records, the mummy board was originally acquired by an English traveler in Egypt during the 1860s-1870s. The mummy itself was most likely left in Egypt, since it has never formed part of the British Museum’s collection. The traveler was part of a group of Oxford graduates touring Luxor, who drew lots to haggle over the coffin lid. All four companions suffered unfortunate fates soon after this purchase. One of the men disappeared into the desert, one was accidentally shot by a servant and had his arm amputated, one lost his entire life’s savings, and one fell severely ill and was reduced to poverty. The mummy board then passed to the sister of one of the men, Mrs. Warwick Hunt, whose household became plagued by a series of misfortunes. When Mrs. Hunt attempted to have the coffin lid photographed in 1887, the photographer and porter both died, and the man hired to translate the hieroglyphs committed suicide. Clairvoyant Madame Helena Blavatsky allegedly detected an evil influence emanating from the mummy board, and convinced Mrs. Hunt to dispose of the object by donating it to the British Museum. Yet tales of the curse would follow. In 1904, journalist Bertram Fletcher Robinson published an article in the Daily Express titled “A Priestess of Death,” detailing the mummy board’s grisly exploits. When he died suddenly three years later, this was attributed to the Unlucky Mummy’s vengeance from beyond the grave. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and avowed spiritualist, claimed that the mummy’s spirit had used “elemental forces” to strike down Robinson.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

For those who wish to see the Unlucky Mummy in person, it is currently located in Room 62 of the British Museum. Hopefully, its curse won’t follow you home…

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 22, 2021 |

Temple in Yangchun where the statue was originally housed. Photo copyright: Lin Wenqing

Last month, the Sanming Intermediate People’s Court of Fujian Province, China announced that the residents of the Yangchun and Dongpu villages had a proprietary right in a Buddha containing the mummified remains of a 1,000-year-old monk. The court ordered its return from Dutch art collector Oscar van Overeem. As one might expect, the story of how this treasured cultural artifact traveled to the Netherlands, and how a civil court might reach such a verdict, has been anything but conventional.

During the Song Dynasty (960-1297), a Buddhist monk named Zhang Gong Liu Quan was a skilled doctor known for his benevolence. In fact, he was credited with helping the local population to survive a plague. He was said to have achieved Nirvana, and in the later years of his life, he prepared his body for self-mumification. Following his death, Zhang Gong’s mummified remains were enclosed in a golden Buddha statue to commemorate his contributions to the community. Thereafter, the practice of worshipping the statue, the Zhanggong Zushi (also called Buddha Zhanggong), has been passed down for almost a thousand years through generations of the local population.

That statue is adorned with elaborate ornamentation representative of the Ming Dynasty, which is consistent with the last time the piece was renovated. The seated Buddha wears two sets of robes: a grey lining covered by a delicately carved outer layer. The outer layer features an intricate network of clouds, knitted lines, and flowers. Accorind to Erick Bruijn, an independent researcher of esoteric Buddhism, the right sleeve and stomach area depict dragons to evoke longevity and “irresistible power.” A black belt is draped over the left shoulder with ends on the left chest and back. The back is also decorated with the Chinese character “佛,” for Buddha. The statute wears a philosophy ring on its left hand surrounded by inscriptions noting “disasters turning into auspicious” and “delivering all living creatures from torment.” According to local records, the piece was renovated in an effort to reverse population decline in the area and bring the people a successful harvest.

Photo owned by Drents Museum

The statue remained in the small village of Yangchun since Zhang Gong’s mummification. There, worship of the statue continued for generations despite a long and sometimes turbulent history. Once, the piece was even buried in a field to avoid destruction during China’s Cultural Revolution. However, the piece went missing in December 1995, when it was stolen and smuggled to Hong Kong. Locals from Yangchun reportedly saw a van traveling through the tiny village where the statue was housed. In the rear seat, they saw a seated figure covered with a blanket, and they assumed it was someone who was ill being taken for medical treatment. Shortly afterwards, they discovered that the statue of the holy man was missing from the temple. Locals were devastated. As stated by one villager, “Zhang Quisan is not a cultural relic…We see him as family. He is one of us.”

Unbeknownst to the villagers, on the other side of the world, the statue appeared for sale. The statute was lost until it was sent to Asian art and antiquities restorer, Carel Kools, who later purchased it in 1997. Upon further testing, Kools was shocked to discover the statue contained a set of mummified remains, although he remained unaware of the subject’s identity. He then sold the work to Oscar van Overeem, an Amsterdam-based architect and respected art collector. The local villagers learned of the statue’s location while it was on loan to the Hungarian National History Museum in 2015.

The two villages demanded the return of the statute and the remains. After negotiations between the villages and Overeem yielded negligible results, the two villages sought to recover the statue through the Netherlands courts. Overeem argued that the “village committee is not to be referred to as a natural person or legal person” under Dutch law and therefore the court was not entitled to hear their claims. The villages responded in kind that under Chinese law, a village committee has standing to act as a party to litigation as a special legal person acting on behalf of village residents, and that such cases are not uncommon in practice.

Photo courtesy of The Economist

The villages also asserted that the object was properly understood to be a “corpse,” as defined under the Dutch Burials and Creations Act, and according to the Act, could not be subject to ownership. They emphasized that the act of mummification was intentional, and “[t]he likely wish of monk Zhang Gong is that through mummification, he would after his death continue to have a spiritual and healing power on his environment, and he would certainly not have agreed that his body would become the subject of (illegal) art trade.” Overeem argued that because most of the organs were absent, the mummy was better classified as “human remains” and not a corpse, drawing on literature supporting the practice of auctioning mummies throughout the U.S., Canada, Britain, and beyond. There were also doubts presented as to whether this was truly the correct Buddha in question and whether Overeem exercised good faith when he purchased the work back in 1995. The villages argued that Hong Kong had a reputation for illegally sourced antiquities at the time, and as a seasoned collector, Overeem should have known to make more detailed inquiries into the work’s provenance and provenience. Under the Dutch Civil Code, collectors must observe necessary prudence when acquiring ancient cultural objects. It is known within “professional art trading circles” that this kind of statue could never have been legally exported from China without a permit. A major collector should have asked for provenance documents and an export permit. Apparently, Overeem did not.

The Dutch case was dismissed in 2018, when the court ruled that the committees were not legal persons (leaving other, more visceral questions for a later date). The villages continued their pursuit, however, in China. In a decision issued last month, the Chinese Court sided with the plaintiffs and ordered Overeem to return the statue within 30 days. Overeem has said separately that he already sold the statue to a Chinese businessman, and that he no longer has any knowledge of its whereabouts. What will happen if and when Overeem does not comply with the Chinese court order is unclear.

The case highlights a change in China’s official policy towards cultural artifacts, in which the nation has begun to demand and litigate for the restitution of looted objects. The mummy is said to have become a smaller Chinese version of the Elgin marbles: an emblem of the despoliation of Chinese culture by foreigners. Unfortunately for many nations around the world, a vast number of significant cultural items are not in secure locations, and thus are vulnerable to falling victim to illicit removal.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 5, 2018 |

The new year is off to a great start with another international repatriation. Later this month, fragments of a mummy will be returned to the Arab Republic of Egypt. The skull and two dismembered hands were taken from Egypt in the 1920s in violation of the nation’s antiquities laws. Leila Amineddoleh served as the cultural heritage law expert for the government.

The new year is off to a great start with another international repatriation. Later this month, fragments of a mummy will be returned to the Arab Republic of Egypt. The skull and two dismembered hands were taken from Egypt in the 1920s in violation of the nation’s antiquities laws. Leila Amineddoleh served as the cultural heritage law expert for the government.

Read about the case HERE.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

The new year is off to a great start with another international repatriation. Later this month, fragments of a mummy will be returned to the Arab Republic of Egypt. The skull and two dismembered hands were taken from Egypt in the 1920s in violation of the nation’s antiquities laws. Leila Amineddoleh served as the cultural heritage law expert for the government.

The new year is off to a great start with another international repatriation. Later this month, fragments of a mummy will be returned to the Arab Republic of Egypt. The skull and two dismembered hands were taken from Egypt in the 1920s in violation of the nation’s antiquities laws. Leila Amineddoleh served as the cultural heritage law expert for the government.