by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Dec 15, 2017 |

Today Amineddoleh & Associates was honored to attend the repatriation ceremony for three looted antiquities from the Temple of Eshmun in Sidon, Lebanon. Our founding partner served as the cultural heritage legal expert for the District Attorney’s Office, providing expertise on Lebanon’s cultural heritage laws for the seizure of a marble sculpture formerly on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Today Amineddoleh & Associates was honored to attend the repatriation ceremony for three looted antiquities from the Temple of Eshmun in Sidon, Lebanon. Our founding partner served as the cultural heritage legal expert for the District Attorney’s Office, providing expertise on Lebanon’s cultural heritage laws for the seizure of a marble sculpture formerly on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

During the ceremony, in which the items were returned to the Lebanese Republic, District Attorney Cyrus Vance addressed the need to protect against looting of art. He discussed the importance of due diligence by museums, auction houses, and collectors. He also acknowledged the work of Matthew Bogdanos, Karin Orenstein, and John Labatt. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Agent Erik Rosenblatt noted the link between organized terror and antiquities looting, mentioning the mounting evidence gathered by HSI. The Lebanese General Consul, Majdi Ramadan, expressed his gratitude for today’s repatriations, and the continued cooperation of the District Attorney’s Office and his nation. And finally, Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO, briefly spoke about the significance of the repatriated pieces and the importance of enforcing laws against looting. She applauded restitution ceremonies and legal action against looting as they signal the law enforcement agency’s willingness to pursue restitution and punish wrongdoing.

After the statements, Matthew Bogdanos, the attorney responsible for working on these repatriations, fielded questions from reporters. He noted that the antiquities were looted during times of conflict. He also clarified that the Metropolitan Museum of Art was not guilty of any wrongdoing, and that his team will continue working to restitute stolen and looted heritage.

It was an honor for Amineddoleh & Associates to play a role in the return of these items. For more information, please visit http://newyork.cbslocal.com/2017/12/15/ancient-sculptures-returned-to-lebanon/ and http://manhattanda.org/press-release/manhattan-district-attorney%E2%80%99s-office-returns-three-ancient-statues-lebanese-republic

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 3, 2017 |

Note: All of the information in this blog post is taken from a publicly filed document. No confidential or privileged information was used in preparing this post.

On September 22, Matthew Bogdanos submitted an application in NY Supreme Court in a matter involving a stolen antiquity from Lebanon. Our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert on this case. It was an honor to once again work with Bogdanos, a talented trial attorney. His track record for excellence is impressive, and the filing in this case is a tour de force of legal writing, reading like a suspenseful crime narrative and primer on cultural heritage law. The document was full of famous art world names, citations to landmark cases and conventions, and introduction to the world of art crime and heritage looting.

On September 22, Matthew Bogdanos submitted an application in NY Supreme Court in a matter involving a stolen antiquity from Lebanon. Our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert on this case. It was an honor to once again work with Bogdanos, a talented trial attorney. His track record for excellence is impressive, and the filing in this case is a tour de force of legal writing, reading like a suspenseful crime narrative and primer on cultural heritage law. The document was full of famous art world names, citations to landmark cases and conventions, and introduction to the world of art crime and heritage looting.

The cast of characters involved in this matter have become household names in the heritage field. The Aboutaams (owners of Phoenix Ancient Art) have been involved in numerous legal battles; Robin Symes, described as a “disgraced” art dealer, has been connected to dozens of pillaged antiquities; Frederick Schultz (former New York gallery owner and former president of the National Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art) served time for dealing in looted Egyptian antiquities; Michael Steinhardt, founder of a hedge fund and referred to as “Wall Street’s Greatest Trader,” has faced many legal controversies for his art collection (including this year’s disputed sale of the Guennol Stargazer at Christie’s); and Frieda Tchacos, a dealer with a history of antiquities violations has been profiled for her role in the illicit antiquities trade. All of these individuals have been featured in books like Chasing Aphrodite and the Medici Conspiracy. In fact, the dispute over the Bull’s Head reads like a redux of the Euphronios Krater debacle at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“the Met”). However, as Bogdanos notes in the government’s filing, the Met acted “admirably” by removing the item from display and delving into the object’s past.

The current controversy involves an antiquity that was purportedly looted from storage in Lebanon during the nation’s civil war. It went missing for decades and then appeared at the Met after it was loaned to the museum by Michael Steinhardt. He had purchased the item from wealthy collectors, Will and Lynda Beierwaltes. Once Steinhardt was informed of the work’s problematic provenance, he demanded a refund for the purchase and transferred title to the object back to the couple.

One of the most interesting aspects of this case is Bogdanos’ discussion about “good faith.” The Beierwaltes are not novice collectors; they owned a collection of antiquities valued at nearly $100 million. As “professional” collectors, did they really use good faith in acquiring the antiquity? As Bogdanos rightly asks: where are the documents related to the object? If an antiquity of such high value (over a million dollars) crosses international borders multiple times, there should be documentation that traces its movements.

“There is no customs declaration form, no shipping document, no air waybill, no tracking form, no insurance form, no invoice, no bill of sale, no photograph, and no mention in any contemporaneous correspondence or email. No proof of any kind of the possession and repeated transportation across oceans and international borders of a two-millennia-old statue valued at more than one million dollars by either of the names listed by the Met on October 20, 2017.” As stated on page 45, “…twenty-four years (1981-2004) of movement across international borders of a million-dollar statue generated four handwritten words, a couple storage invoices, and one piece of paper from the infamous Robin Symes. A neon sign flashing ‘stolen’ would have been more subtle and less insidious.”

One of the disturbing aspects of this controversy is the allegation that the sculpture was taken during the civil war in Lebanon. If true, then the item was pilfered by opportunists taking advantage of political upheaval to steal priceless and irreplaceable treasures. Sadly, this type of theft occurs around the world and is still common today, particularly prevalent in Syria and Iraq.

Purchasing items without complete provenance is risky. As I explained in this editorial in The Guardian, looted antiquities are problematic from an investment perspective. Bogdanos warns against this risk, stating “The obvious, but all-too-often ignored, risks attendant to never asking about ownership history is that the buyer may one day have that purchase seized and confiscated as stolen property. Here, the absence of the required inquiry, not only subjects the Beierwaltes to potential prosecution for criminal possession of stolen property, but it also defeats any claim that they were good-faith purchasers of the Bull’s Head.”

As outlined in the government’s conclusion, there are a host of important facts to recognize in this case. (1) The Bull’s Head was excavated in 1967 and stolen in 1981 during a civil war, nearly 50 years after Lebanon’s patrimony laws (the laws vest ownership of all discovered antiquities in the nation). (2) The sculpture surfaced in the hands of Robin Symes in NY in early 1996. As revealed by several international investigations, Symes was a major participant in an antiquities trafficking network in the 1980s and 1990s. The network’s black-market supply chain started with tomb raiders, passed through the launderers and middle men, and terminated at the demand end with collectors, like the Beierwaltes. (3) The Symes-Beierwaltes relationship was responsible for 98% of the vast Beierwaltes Collection, valued at almost $100 million in 2006. The acquisition of the collection appears to have coincided with the peak of the Medici, Becchina, and Symes empire of loot. (4) There is a shocking lack of documentation produced by the Beierwaltes. (5) The lack of records is especially telling for collectors involved in the art trade for 62 years. (6) The Beierwaltes avoided submission of any materials pursuant to discovery requests, despite multiple subpoenas and repeated requests. There is also no evidence concerning how Robin Symes acquired the Bull’s Head or whether he legally possessed it. (7) Lebanon made commendable efforts to protect and to recover its cultural heritage.

A copy of the the government’s filing can be found on the Chasing Aphrodite website: https://chasingaphrodite.com/2017/09/24/the-sidon-bulls-head-court-record-documents-a-journey-through-the-illicit-antiquities-trade/

Our founder at the repatriation ceremony in 2017

UPDATE: The Bull’s Head (as well as two other pieces) were returned to Lebanon in December 2017.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Aug 1, 2017 |

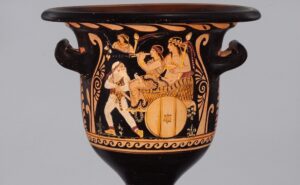

Last night, Tom Mashberg of the NY Times broke the story about an ancient vase that was seized from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“the Met”). The 2,300-year-old object, the “Python Vessel,” had been displayed at the NY institution since 1989, when it was purchased from Sotheby’s for $90,000. Matthew Bogdanos, a celebrated and Assistant District Attorney in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office (as well as author and colonel in the United States Marine Corps Reserves), seized the work based on evidence that it was looted from Italy in the 1970s. He was presented with evidence from forensics archaeologist Christos Tsirogiannis that the vase was connected to well-known looter Giacomo Medici. Medici was convicted in a Rome court of conspiring to traffic in ancient treasures, and is perhaps best known for his role in the looting and trafficking of the Euphronios Krater.

Last night, Tom Mashberg of the NY Times broke the story about an ancient vase that was seized from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“the Met”). The 2,300-year-old object, the “Python Vessel,” had been displayed at the NY institution since 1989, when it was purchased from Sotheby’s for $90,000. Matthew Bogdanos, a celebrated and Assistant District Attorney in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office (as well as author and colonel in the United States Marine Corps Reserves), seized the work based on evidence that it was looted from Italy in the 1970s. He was presented with evidence from forensics archaeologist Christos Tsirogiannis that the vase was connected to well-known looter Giacomo Medici. Medici was convicted in a Rome court of conspiring to traffic in ancient treasures, and is perhaps best known for his role in the looting and trafficking of the Euphronios Krater.

The Euphronios krater (also known as the Sarpedon Krater) is a red-figure vase attributed to the famous Greek painter Euphronios and the potter Euxitheos, dating from around 515 BCE. The Euphronios Krater is believed to have been illegally excavated sometime in December 1971 near Cerveteri, Italy, from the Greppe di Sant’Angelo region of the town’s ancient Etruscan cemetery, by tombaroli (tomb raiders). The looters sold the vase to Medici who them smuggled it into Switzerland and sold it for $350,000 to an antiquities dealer, Robert Hecht. By this point, the vase, which had been found in a remarkably excellent state, was intentionally damaged and broken into fragments to more easily illegally export it. After restoring the fragmented object, in February 1972, Hecht wrote to Dietrich von Bothmer, the Met’s Curator of Greek and Roman Art, about the krater. In August 1972, the Met bought the vase for $1 million.

Throughout the 1990s, Italian authorities investigated Giacomo Medici, and they eventually found enough evidence to bring legal claims against him. The Italian authorities also demanded the repatriation of the Euphronios Krater from the Met. The case drew international attention and led to the restitution of dozens of Italian artifacts from institutions across the country, including the Met, the MFA in Boston, and the Princeton Art Museum. The return of objects also led to the cultural exchange of artifacts from Italy in the form of long-term loans to the American institutions repatriating looted good. The Euphronios Krater has since returned home and is now on display at the Archaeological Museum of Cerveteri.

In the case of the Python Vessel, Mashberg reports that the Met removed the item from its viewing case and that it is now in the custody of law enforcement agents.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 4, 2016 |

The past week has been an art lawyer’s dream, with major news items about cultural heritage destruction, the recovery of stolen art, a lawsuit against a major museum, and the rediscovery of a painting by an Old Master.

Cultural Heritage Destruction and Crimes

Last Tuesday, cultural heritage made the headlines. Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi faced a war crimes charge under Article 25 of the Rome Statute. This is the first time the International Criminal Court (ICC) had attempted to prosecute the “destruction of buildings dedicated to religion and historical monuments” as a war crime. In August, the trial against Al-Mahdi opened before Trial Chamber VIII at the ICC in The Hague, the Netherlands. The Malian national admitted guilt as to the war crime consisting of the destruction of historical and religious monuments in Timbuktu, Mali in 2012. He “exercised joint control over the attacks” by planning, leading and participating in them, supplying pick-axes and in one case a bulldozer.

Al-Mahdi expressed remorse for his involvement in the destruction of 10 mausoleums and religious sites in Timbuktu dating from Mali’s 14th-century golden age as a trading hub and center of Sufi Islam, a branch of the religion seen as idolatrous by some hardline Muslim groups. It was the first international trial focusing on the destruction of historical and religious monuments, and the first ICC case where the defendant admitted guilt. Last Tuesday, al-Mahdi was given 9 years in prison for his crimes. In handing down a 9-year sentence, rather than the maximum of 30 years, the judges stated that they took into account al-Mahdi’s “genuine remorse, deep regret and deep pain” and his calls on other Muslims not to make the same mistakes he had made.

Recovery of Stolen Art

Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

On Friday, another major art announcement was made—two stolen Van Gogh paintings were recovered by Italian military police, the Carabinieri. The paintings were stolen in 2002 from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam when two art thieves used a ladder to climb up to the roof of the museum, and broke into the building. The pair stole two paintings, View of the Sea at Scheveningen and Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen.

Last week, the paintings were recovered in Naples, Italy when authorities found the works after a sting operation to infiltrate an organized crime group, the Camorra. The paintings were stored in one of the houses of an international drug trafficker. According to press release from the Van Gogh Museum, the seascape has a patch of damage on the bottom left corner, but otherwise the paintings are in good condition. It is not known when the works will return to the Netherlands since they will likely be used as evidence in a trial.

Lawsuit against the Metropolitan Museum of Art

On Friday, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was sued over one of its most valuable Picasso works, The Actor. The estate of a German Jewish businessman, Paul Leffmann, asserts that the museum does not have good title to the painting because Leffmann was forced to sell it at a low price after fleeing the Nazis. The estate claims that the sale was made under duress. The law firm for the estate, Herrick Feinstein alleged in the court filing that the museum “did not disclose or should have known that the painting had been owned by a Jewish refugee, Paul Leffmann, who had disposed of the work only because of Nazi and Fascist persecution.” The lawyers said they had negotiated with the Met for several years, while the Met investigated the claim, but they had never been able to reach a settlement. The museum asserts the Leffmanns had made no claim on the painting after the war, when they did try to reclaim property they had been forced to sell.

Rediscovery of a Raphael

And finally, on Sunday, an interesting attribution matter was announced in the news. A painting likely to be the work of Raphael was ‘rediscovered’ in the Haddo House, in Scotland. The painting of Madonna was obscured by darkened varnish and was misattributed to a minor hand. In 1899, it was valued as a copy for just about $25 dollars. If it is truly a Raphael, it would be worth about $25 million today.

And finally, on Sunday, an interesting attribution matter was announced in the news. A painting likely to be the work of Raphael was ‘rediscovered’ in the Haddo House, in Scotland. The painting of Madonna was obscured by darkened varnish and was misattributed to a minor hand. In 1899, it was valued as a copy for just about $25 dollars. If it is truly a Raphael, it would be worth about $25 million today.

Famous art historian Bendor Grosvenor was at the Haddo House to view other paintings for a BBC television series when he was struck by the Raphael tucked away in the corner. He discovered that the painting was bought as a Raphael in the early 19th century and exhibited as such in 1841. Afterwards, it was downgraded to “after Raphael”, and eventually attributed to a minor Renaissance artist, Innocenzo Francucci da Imola.

The story of this Raphael rediscovery will be featured on 5 October in a new BBC4 series, Britain’s Lost Masterpieces, co-presented by Grosvenor.

Today Amineddoleh & Associates was honored to attend the repatriation ceremony for three looted antiquities from the Temple of Eshmun in Sidon, Lebanon. Our founding partner served as the cultural heritage legal expert for the District Attorney’s Office, providing expertise on Lebanon’s cultural heritage laws for the seizure of a marble sculpture formerly on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Today Amineddoleh & Associates was honored to attend the repatriation ceremony for three looted antiquities from the Temple of Eshmun in Sidon, Lebanon. Our founding partner served as the cultural heritage legal expert for the District Attorney’s Office, providing expertise on Lebanon’s cultural heritage laws for the seizure of a marble sculpture formerly on loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

On September 22, Matthew Bogdanos submitted an application in NY Supreme Court in a matter involving a stolen antiquity from Lebanon. Our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert on this case. It was an honor to once again work with Bogdanos, a talented trial attorney. His track record for excellence is impressive, and the filing in this case is a tour de force of legal writing, reading like a suspenseful crime narrative and primer on cultural heritage law. The document was full of famous art world names, citations to landmark cases and conventions, and introduction to the world of art crime and heritage looting.

On September 22, Matthew Bogdanos submitted an application in NY Supreme Court in a matter involving a stolen antiquity from Lebanon. Our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert on this case. It was an honor to once again work with Bogdanos, a talented trial attorney. His track record for excellence is impressive, and the filing in this case is a tour de force of legal writing, reading like a suspenseful crime narrative and primer on cultural heritage law. The document was full of famous art world names, citations to landmark cases and conventions, and introduction to the world of art crime and heritage looting.

And finally, on Sunday, an interesting attribution matter was announced in the news. A painting likely to be the work of Raphael was ‘rediscovered’ in the Haddo House, in Scotland. The painting of Madonna was obscured by darkened varnish and was misattributed to a minor hand. In 1899, it was valued as a copy for just about $25 dollars. If it is truly a Raphael, it would be worth about $25 million today.

And finally, on Sunday, an interesting attribution matter was announced in the news. A painting likely to be the work of Raphael was ‘rediscovered’ in the Haddo House, in Scotland. The painting of Madonna was obscured by darkened varnish and was misattributed to a minor hand. In 1899, it was valued as a copy for just about $25 dollars. If it is truly a Raphael, it would be worth about $25 million today.