by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Apr 19, 2021 |

Join our founder and other experts for an important event addressing the effects of international sanctions on the preservation and protection of cultural heritage. Iran’s astounding cultural heritage has developed over many millennia. But during the past decade, Iranian heritage has had to contend with the sanctions era, a period in which political and practical challenges have made heritage management, research, and cultural tourism more difficult. In this unique webinar hosted by the Heritage Management Organization and the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, these challenges will be discussed by experts with first-hand knowledge of how Iran’s cultural sector has had to adapt in order to remain connected to global exchanges on arts, culture, and shared patrimony.

Join our founder and other experts for an important event addressing the effects of international sanctions on the preservation and protection of cultural heritage. Iran’s astounding cultural heritage has developed over many millennia. But during the past decade, Iranian heritage has had to contend with the sanctions era, a period in which political and practical challenges have made heritage management, research, and cultural tourism more difficult. In this unique webinar hosted by the Heritage Management Organization and the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, these challenges will be discussed by experts with first-hand knowledge of how Iran’s cultural sector has had to adapt in order to remain connected to global exchanges on arts, culture, and shared patrimony.

The discussion will be moderated by Kyle Olson of the University of Pennsylvania, whose five-part article series published by the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, explored the impact of sanctions on the cultural heritage sector in Iran. Our founder has written about the effects of politics on heritage (with an emphasis on Iran) in a law review article published in 2020, available here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3572987

Our law firm addressed the topic in a blog post here (https://www.artandiplawfirm.com/why-cultural-heritage-should-not-be-destroyed-to-punish-a-nation/). Our founder even drafted the official statement of the Lawyers’ Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation (LCCHP) calling for the protection of heritage in Iran.

Register for the April 27 event here: https://mailchi.mp/bourseandbazaar.com/iran-heritage-management-under-sanctions

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 6, 2020 |

In October I was invited to speak at a symposium, “Lost, Stolen, Destroyed: Patrimony in Peril,” hosted by North Carolina Journal of International Law at University of North Carolina School of Law. Earlier this week I submitted a 35-page article (to be published in the spring). One of my central theses is that cultural heritage is different than other property because it is owned by sovereign nations on behalf of its citizens and held for all humanity.

People and nations have complicated relationships with cultural heritage, the exploitation of its ownership and protection, and the non-commercial value of shared heritage. Cultural heritage has long been treated differently than other property. In 1813, a Canadian court, the Vice-Admiralty Court of Halifax, stated that “The arts and sciences…[are] the property of mankind at large, and as belonging to the common interests of the whole species.” The Marquis de Somerueles, Vice-Admiralty Court of Halifax, Nova Scotia Stewart’s Vice-Admiralty Reports 482 (1813). Essentially, cultural heritage is not simply property, but items that belong to all humanity. This is evidenced in the manner in which courts treat these objects, the laws that regulate their ownership and trade, and the fact that they are not exploited as purely commercial goods. They are remnants of our common past. But even more so, these items encapsulate and represent our shared history. Their value goes beyond monetary considerations and material aspects of the object in a collection, but they represent human achievements and history that transcends material considerations.The significance of our shared heritage is so great that the heritage objects receive special treatment during times of conflict, as nations have regularly come together to protect cultural heritage during war. Internationally, cultural heritage has been viewed as an extension of human rights frameworks. Indeed, international law treats attacks against cultural heritage as crimes, including war crimes and crimes against humanity, in some instances.

The statements (via Twitter) made by Trump threatening to destroy Iranian cultural heritage sites are troubling, in part because the United States has a long history of protecting heritage sites. It was one of the first nations to enact a code to protect culture during conflict. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln signed the Lieber Code outlining military conduct for Union soldiers during the American Civil War. It was one of the earliest texts of modern humanitarian law, addressing the treatment of cultural heritage and emphasized the importance of protecting this material during war. The code provided that property belonging to churches, hospitals or charitable institutions, schools, universities, academies, observatories, museums, or scientific institutions be treated differently than other institutions; namely, that they are not subject to appropriation. The Lieber Code even outlined post-conflict resolutions for appropriation in the form of peace treaties, and notes that “in no case shall [the property removed from these institutions] be sold or given away…nor shall they ever be privately appropriated, or wantonly destroyed or injured.” Scholars have noted that the code influenced the Hague Conventions and Regulations of 1899 and 1907.

Sadly, heritage destruction has always been a part of war. In another paper I published, “Cultural Heritage Vandalism and Looting: The Role of Terrorist Organizations, Public Institutions and Private Collectors,”I discuss the power of cultural heritage, andhow culture can be weaponized and used as propaganda. The paper briefly discusses the history of cultural vandalism and its power to symbolize defeat and power. These tactics have been deployed for thousands of years, and were used up through modern times with the actions by Napoleon, Hitler, the Taliban and ISIS. Although the paper primarily focuses on ISIS, the US President threatens to use these same tactics. Just as ISIS ignorantly destroys heritage that they think is “foreign,” Trump is threatening the same behavior, and does not comprehend that it’s shared heritage. A blurb from the paper reads:

“With the use of social media, destruction has been more widely observed and knowledge of its occurrence has spread globally, allowing terrorist organizations to create global fear within an instant. There have been attempts made by other ruling parties to annihilate the past, but the use of media to publicize atrocities sets these crimes apart.”

Trump, with his overused Twitter account, does the same, creating terror and propaganda.

The paper also addresses cultural heritage as a human right. Current ideology about human rights traces its origins to 1948 when the United Nations, motivated by the horrors of the Holocaust during World War II, promulgated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 27 asserts that culture is a human right, stating “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.” More recently, the significance of cultural heritage was expressed in UNESCO’s Declaration Concerning the International Destruction of Cultural Heritage (2003), asserting that heritage is linked to human dignity and identity, and access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage has a strong legal basis in human rights norms, stating “cultural heritage is an important component of the cultural identity of communities, groups and individuals and or social cohesion, so that its intentional destruction may have adverse consequences on human dignity and human rights.” In 2011, the Special Rapporteur at the UN submitted a report extensively outlining arguments in favor of this treatment. The report articulates that cultural heritage is important not only in itself, but also in relation to its human dimension, as it holds significance for individuals and groups for their identity and development.

Heritage professionals and government officials have used military forces to prevent destruction. Art professionals and soldiers, as with the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program during World War II (members of the group are now famously known as “The Monuments Men”), were celebrated for their work to preserve heritage, and now the US president is threatening destruction. Our heritage has already fallen victim to centuries of conflict, natural disasters, and terrorism, and rather than protecting priceless heritage, the US President threatens more destruction.

Heritage destruction has been classified as a war crime, and ISIS’s actions have been categorized as criminal. In 2015, then Secretary-General of the UN, Ban Ki-moon aptly stated, “The deliberate destruction of our common cultural heritage constitutes a war crime and represents an attack on humanity as a whole.” The UN 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict explicitly prohibits using monuments and sites for military purposes and harming or misappropriating cultural property in any way. The convention applies to immovable and movable cultural heritage, including monuments of architecture, art or history, archaeological sites, works of art, manuscripts, books and other objects of artistic, historical or archaeological interest, as well as scientific collections of all kinds regardless of their origin or ownership. The stated purpose of the convention is to safeguard heritage by establishing an agreement among States Parties to respect cultural property in their own territory as well as that of other Parties. The Parties consent to abstain from exposing cultural property to damage, except in cases of military necessity and to prohibit theft or vandalism, including those actions by domestic and foreign military forces. The convention prohibits nationals from “any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property.”

Just as the 1954 Hague Convention was prompted by destruction and looting during the Second World War, nations convened in 1991 partly due to damage during the late 1980s and early 1990s, in the Balkans. The Second Protocol to the Hague Convention, which was adopted in 1999, further expounds the provisions of the Convention relating to safeguarding of and respect for cultural property and conduct during conflict. Importantly, it defines individual criminal responsibility and jurisdictional procedures in the event of violations, with specification of sanctions to be imposed for grave violations with respect to cultural property. The Convention states that individuals may be criminally responsible, and that this culpability extends to persons other than individuals who directly commit acts in defiance of the Convention.

Under Article Five of the Rome Statute, the ICC has jurisdiction to try individuals for war crimes. The ICC considers the destruction of cultural property a war crime. Under the Rome Statute, ICC can exercise jurisdiction in the following circumstances: (1) A State Party refers the case to the ICC Prosecutor in accordance with Article Fourteen; (2) the Security Council of the UN refers the case to the ICC Prosecutor in according with Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations; or (3) the ICC Prosecutor initiates an investigation under Article Fifteen of the Rome Statute. In the instance that the ICC does not exercise jurisdiction, the UN Security Council may establish an ad hoc tribunal for “grave breaches” of the Geneva Convention of 1949. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (“ICTY”) has held individuals accountable for damage done to religious, artistic, scientific or historic institutions and structures. The ICTY’s prior rulings on protection of cultural heritage during conflict have precedential effect and have risen to the status of customary international law; thus, they are enforceable, even against states not party to international humanitarian treaties.

Another theme in my paper is that heritage should not be withheld from its rightful owner because the US lacks diplomatic channels with a country. I used Iran as an example (naively unaware that this topic would take center stage during the first week of the new decade). In 2000, an ancient silver griffin rhyton on a flight from Switzerland to the US, and then sold for close to a million dollars. It was discovered that it was looted, and the rhyton was confiscated by the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and sent to a warehouse in Queens, NY that stores over 2,5000 objects.

After languishing for over a decade in storage, the rhyton was returned to Iran in what the news called “archaeo-diplomacy.” At the time, the State Department stated, “The return of the artifact reflects the strong respect the United States has for cultural heritage property — in this case, cultural heritage property that was likely looted from Iran and is important to the patrimony of the Iranian people…It also reflects the strong respect the United States has for the Iranian people.” The State Department also noted the importance of the object to all humanity: “It is considered the premier griffin of antiquity, a gift of the Iranian people to the world, and the United States is pleased to return it to the people of Iran.”

In 2017 and 2018, I had the opportunity to work on a matter involving the repatriation of a looted relief from Persepolis (Iran’s most significant cultural heritage site). In 2018, New York Supreme Court ordered the return of a bas-relief that was stolen in the 1930s from Persepolis, in Iran. During that time, I had the chance to work with Persian/Iranian heritage specialists in Iran, the US, and the UK. We all proudly worked together with US officials to return stolen property to its rightful home. UNESCO ranks Iran seventh in the world in terms of possession historical monuments, museums and other cultural sites, and the nation has 24 UNESCO world cultural heritage sites. As a nation, Iran places great value on its heritage, and has taken actions to protect it, with the nation’s first patrimony laws passing in 1930.

Iranian authorities work to safeguard its sites, and the government invests in its cultural sites. The Islamic Republic of Iran has also joined other nations to protect heritage. The nation joined the 1954 Hague Convention, the 1954 Protocol (First Protocol) to the 1954 UNESCO Convention (Hague Convention), the 1970 UNESCO Convention, the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention, the 1999 Protocol (Second Protocol) to the 1954 UNESCO Convention, and the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

For a deeper look into some of these issues, please read “Cultural Heritage Vandalism and Looting: The Role of Terrorist Organizations, Public Institutions and Private Collectors” and a current draft of the “Politicizing of Cultural Heritage.”

Cultural heritage is powerful—it has ability to unify people to find a common humanity. It transcends monetary interests or even the national interests of a population. Cultural heritage is significant for all mankind. Destroying Iran’s heritage will not only punish Iranian citizens, but it will punish all citizens of the world, today and into the future. Iran’s heritage is world heritage, and its destruction would be a painfully ignorant act that will harm us all. It is the responsibility of our leaders to protect our shared treasures and protect them to understand mankind’s greatest achievements.

This editorial was written by our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh.

As a board member of the Lawyers’ Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation (LCCHP), Ms. Amineddoleh also wrote a statement on behalf of LCCHP standing with colleagues around the world to condemn threats made by the United States President to destroy cultural sites in Iran. You can read the advocacy statement here: Iran Cultural Property Statement 1.8.2020

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 3, 2018 |

Note: All of the information in this blog post is taken from a publicly filed document. No confidential or privileged information was used in preparing this post.

Last month, Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos petitioned the NY Supreme Court to turn over an Achaemenid limestone bas-relief that had been looted from Iran. Referred to as a “Persian Guard Relief,” the rare object was stolen from Persepolis in 1935. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, was instrumental in the filing of this case.

Last month, Assistant District Attorney Matthew Bogdanos petitioned the NY Supreme Court to turn over an Achaemenid limestone bas-relief that had been looted from Iran. Referred to as a “Persian Guard Relief,” the rare object was stolen from Persepolis in 1935. Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, was instrumental in the filing of this case.

Persepolis, in current day Iran, is one of the world’s most treasured historical sites, with its name derived from Greek, meaning “Persian city.” Persepolis is considered by UNESCO to have “outstanding universal value.” UNESCO describes Persepolis as “magnificent ruins…among the world’s greatest archaeological sites… among the archaeological sites which have no equivalent and which bear unique witness to a most ancient civilization.” In 1931 excavations were begun at the site, and UNESCO declared the ruins a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Persepolis

© BornaMir/iStock.com

The ancient city, dating back to at least 515 B.C., was the capital of the Achaemenid Empire. Persepolis was built in terraces up from the river Pulwar to rise on a larger terrace of over 125,000 square feet, partly cut from a mountain. Darius I began construction of the site, and it developed until the Greeks plundered and razed the city under the leadership of Alexander the Great in 333 BC (purportedly in retribution for the destruction of the Parthenon by the Persians in 480 BC). The city was widely known as spectacular and breath-taking. As part of the site, Darius I built a palace known as the “Apadana,” used for official audiences. The looted relief at issue was stolen from this great hall.

The looted limestone bas-relief was stolen from Persepolis in 1935, during official excavations completed by the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. Authorities were alerted to the theft, and the Iranian government attempted to find and recover the piece, but it disappeared and entered the global black market, eventually making its way into a Canadian museum. Decades later, it was stolen from the museum, recovered, and then appeared at TEFAF in New York in the fall of 2017. At that point, the work was seized by the NY District Attorney’s Office after they learned of the work’s illicit origins. Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, had informed authorities about the piece after learning about its plundered past by Dr. Lindsey Allen, Lecturer in Greek & Near Eastern History at King’s College in London. As the result of several years examining fragmentary reliefs from the site in museums around the world, and searching archives for their histories, Dr. Allen suspected the relief was looted. When Wace exported the relief for TEFAF, Dr. Allen contacted Ms. Amineddoleh, and explained why she thought the work was stolen.

Iran safeguards Persepolis due to its historic significance. In fact, Iran protects all of its cultural heritage, with the nation’s first patrimony laws passing in 1930. Because of these laws, there is no way that the relief left Iran legally, absent permission from the cultural ministry. Ms. Amineddoleh served as an expert to the District Attorney’s Office in advising on the relevant cultural heritage laws.

The eastern stairs at the Apadana in 1933.

(Photo: The Oriental Institute of University of Chicago, Photo 23188/ Neg.Nr. 12822

https://oi-idb.uchicago.edu/id/bec348b2-7e3c-49fd-8fd6-e9f057c92c4e)

The District Attorney’s Office submitted its turnover request on May 24 (read the document HERE: 18-05-24 PGR Motion for Turnover-reduced), but the case may carry on for some time. The limestone relief, part of an historical complex, has significance not only to the people of Iran, but to archaeologists and classicists, and to anyone visiting Iran’s most celebrated archaeological site. The limestone relief’s theft from Persepolis was tragic and damaging to the site, and hopefully the limestone guard will return to his home protecting the ancient site. The guards are designed to work in the site as a collective, not as individuals. Their fragmentation removes their context, and high-profile sales make other Achaemenid ruins potentially vulnerable to plunder.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 22, 2018 |

Photo: Courtesy of University of Chicago

After a legal battle spanning over a decade, the fate of the Persepolis Collection at the University of Chicago has been determined. In a unanimous decision, the United States Supreme Court affirmed a decision by the federal appeals court in Chicago, ruling in favor of Iran. In an opinion written by Justice Sotomayor, the court writes that the plaintiffs cannot collect on a judgment against Iran by transferring ownership of antiquities.

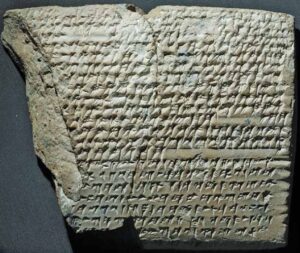

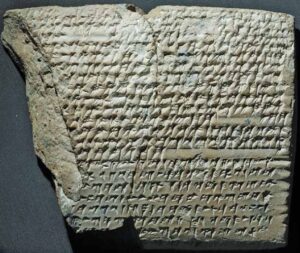

This judgment stems from a case in which victims of a terror attack in Israel sued Iran and received a $71.5 million judgment against the Middle Eastern nation. Iran did not pay the judgment, and so the plaintiffs attempted to seize assets located in the US under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). The items they attempted to seize include the Persepolis Collection, a collection of 30,000 thousand clay tablets, many with Elamite inscriptions, loaned from Iran to the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute in 1937. The rare and historically priceless artifacts were excavated by the university’s archeologists in the 1930s in the ancient city of Persepolis. The finds were then given as a long-term loan to the Oriental Institute for cataloging, researching, and translating.

The victims argued that the objects could be seized under the FSIA (the same law used to restitute Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as “The Woman in Gold,” to Maria Altmann). The FSIA grants immunity to foreign states, except for nations (like Iran) designated as state sponsors of terrorism. In addition, the FSIA also exempts certain foreign-owned property in commercial use in the US. In this case, the lower court found that the FSIA exemptions cover property used by the foreign state, but do not include property used by a third party, like the university.

In finding that an exception to the FSIA does not apply, the victims will be unable to seize these objects. A representative from the University of Chicago, Marielle Sainvilus, stated, “The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago is committed to preserving and protecting a collection of Persian artifacts on loan from the Iranian government, which are among the region’s most important historical documents…These ancient artifacts, along with the Oriental Institute’s own Persian collection, have unique historical and cultural value. Today’s ruling reaffirms the University’s continuing efforts to preserve and protect this cultural heritage.”

In 2006, the then-director of the Oriental Institute Gil Stein described his disbelief, “It’s a bizarre, almost surreal kind of thing… You’d have to imagine how we would feel if we loaned the Liberty Bell to Russia and a Russian court put it up for auction,” Stein said.

The significance of objects from Persepolis cannot be understated. Persepolis is considered by UNESCO to have “outstanding universal value.” UNESCO describes Persepolis as “magnificent ruins…among the world’s greatest archaeological sites… among the archaeological sites which have no equivalent and which bear unique witness to a most ancient civilization.”

Join our founder and other experts for an important event addressing the effects of international sanctions on the preservation and protection of cultural heritage. Iran’s astounding cultural heritage has developed over many millennia. But during the past decade, Iranian heritage has had to contend with the sanctions era, a period in which political and practical challenges have made heritage management, research, and cultural tourism more difficult. In this unique webinar hosted by the Heritage Management Organization and the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, these challenges will be discussed by experts with first-hand knowledge of how Iran’s cultural sector has had to adapt in order to remain connected to global exchanges on arts, culture, and shared patrimony.

Join our founder and other experts for an important event addressing the effects of international sanctions on the preservation and protection of cultural heritage. Iran’s astounding cultural heritage has developed over many millennia. But during the past decade, Iranian heritage has had to contend with the sanctions era, a period in which political and practical challenges have made heritage management, research, and cultural tourism more difficult. In this unique webinar hosted by the Heritage Management Organization and the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, these challenges will be discussed by experts with first-hand knowledge of how Iran’s cultural sector has had to adapt in order to remain connected to global exchanges on arts, culture, and shared patrimony.

Amineddoleh & Associates is excited to share some great news. A looted Persian artifact is returning to Iran. Back in the autumn, our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, brought the object to the attention of the Manhattan DA’s Office after receiving a tip from Dr. Lindsay Allen. The DA began investigating the piece and then seized it from TEFAF. After months of battling over this rare and magnificent work, the piece is being repatriated to Iran. In addition to being the “informant,” Ms. Amineddoleh also served as the heritage law expert in this matter, so this case is particularly exciting for our law firm. Congratulations on the excellent work done by the entire Antiquities Trafficking Unit at the Manhattan DA’s Office.

Amineddoleh & Associates is excited to share some great news. A looted Persian artifact is returning to Iran. Back in the autumn, our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, brought the object to the attention of the Manhattan DA’s Office after receiving a tip from Dr. Lindsay Allen. The DA began investigating the piece and then seized it from TEFAF. After months of battling over this rare and magnificent work, the piece is being repatriated to Iran. In addition to being the “informant,” Ms. Amineddoleh also served as the heritage law expert in this matter, so this case is particularly exciting for our law firm. Congratulations on the excellent work done by the entire Antiquities Trafficking Unit at the Manhattan DA’s Office.