by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 20, 2020 |

For decades, art institutions have struggled to find a compelling response to concerns raised over owning and possessing art and antiquities taken and exported during periods of colonialism. Critics argue that it is unethical to continue holding works that were sourced during times of conflict or subjugation, and often taken as trophies of war or as symbols of power over foreign subjects. By doing so, it deprives the original owners of their rights. Critics also argue that displaying these objects in a foreign museum strips them of essential cultural context. While the debate over such works is nothing new (nations such as Greece, Egypt, India and China have been seeking repatriation of objects for decades), recent protests against racial injustice across the globe have brought the conversation out of museum boardrooms and into the spotlight.

One of the Benin Bronzes at the British Museum. Copyright: British Museum

As museums across Europe begin to reopen, Dan Hicks, a professor and senior curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, has begun the arduous tasking of evaluating the museum’s collection of more than 600,000 works representing almost every country across the globe. Hicks acknowledges that displaying works of cultural significance without proper context risks telling a revisionist version of history. The professor has received acclaim for his efforts to re-introduce the museum’s collection to the public from the perspective of the works’ countries of origin. “This is very specifically about a period of time when our anthropology museums were used for purposes of institutional racism, race science, the display of white supremacy. At this moment in history, it could not be more urgent to remove such icons from our institutions.” Hicks also believes in deaccessioning and returning works that were illicitly seized, including notable objects such as the Benin Bronzes. The bronzes, which are found in many prominent museums around the world, were seized by British soldiers during a punitive raid on the Kingdom of Benin in 1897 (modern day Nigeria). To Hicks, the decision is simple: “It is a matter of respect and being treated equally. If you steal people’s heritage, you’re stealing their psychology, and you need to return it.” It remains to be seen whether museums will adopt this approach as the public continues applying pressure on museums to reconcile with a troubling past.

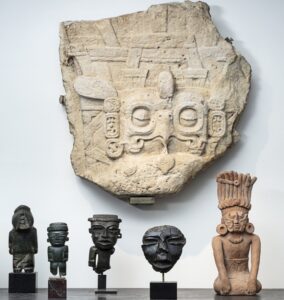

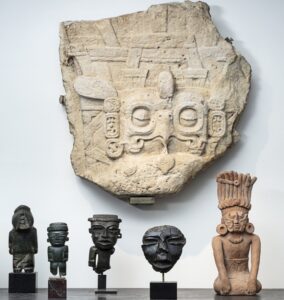

The large carved relief showing a Maya king’s headdress with an owl motif is among works to be sold at auction in Paris. Copyright: Millon and Assoc.

It is important to note that this problem is not exclusive to European countries with an imperialistic past; culturally significant works are still being looted and sold on the open market today. In particular, works from Africa and South America are becoming increasingly popular among art collectors, bringing stolen or looted works to the surface of the market. Amineddoleh & Associates LLC recently discussed two such works which were sold at auction in Paris despite claims that they were looted in violation of local law. In contrast, another French auction house recently pulled a Mayan sculpture from its sale after allegations that the piece was clearly stolen spurred public outcry. Archeologists had previously documented the piece at the ancient city of Piedras Negras, in modern day Guatemala, placing its export during the 1960s and virtually eliminating the possibility that it was exported legally. The Guatemalan Embassy in Paris released a statement once it was agreed the work would be withdrawn stating that negotiations with the sellers were underway. The close proximity of these two sales with different outcomes demonstrates that countries have not yet determined a reliable means of repatriating looted artwork. The significance of this issue was underscored recently as an Interpol sting led to the seizure of approximately 19,000 stolen artifacts, including pre-Columbian relics, suggesting the illicit market for such goods is thriving. In fact, just last year a French auction house sold dozens of Mexican artifacts, despite Mexico’s demand for their return. Hopefully, countries will find it easier to have culturally significant works returned as the public becomes more aware of the issue and ask institutions to be held accountable.

Collectors must also be aware that purchases of cultural artifacts may be legal at the time of sale, but subject to scrutiny and criticism later on. It is imperative to consult knowledgeable professionals before adding potentially questionable items to a collection, whether public or private. Amineddoleh & Associates prides itself on its knowledge of the art and cultural heritage market, and we assist collectors and purchasers in carrying out responsible transactions.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 12, 2017 |

All image rights owned by Tamar

In light of stories coming out of Israel about the illicit antiquities trade, we are pleased to share a blog post by Alexia V. Ogden, a law student based in the UK.

The Israeli state enacted the Antiquities Law of 1978 to crack down on the illicit trade of antiquities. Given the nature of the Palestine-Israeli conflict, cultural heritage sites across the area have suffered extensive looting. However, dating as far back as the second century, religious pilgrims have long been attracted to the Lands of the Bible and many were encouraged by religious officials to bring back relics (Kersel 2008: 22). The search for antiquities and relics heightened during the time of the Crusades and continued throughout the Ottoman period until the present day. In response to the extensive expropriation of cultural property, the 1978 Antiquities Law declared national ownership over all archaeological material found after its enactment and banned excavation without a permit. Nevertheless, an offshoot of the law was a legalised trade in antiquities; the sale of items already on the shops’ shelves was permitted, so long as these were acquired prior to 1978.[1] This has led some to associate Israel with a “collector’s paradise” (Gopher et al 2002: 191).

During the rule of the Ottoman Empire and until 1884, the discovery of cultural patrimony functioned as follows: one third of the archaeological find went to the private landowners, the second third went to the excavator, and the last part went to the state. This resulted in Europeans buying lands and then excavating them, so that two thirds of the archaeological treasures belonged to them. The 1869 Ottoman regulation, which was re-promulgated in 1872 and comprised of only seven articles, was the first Ottoman decree concerning antiquities.[2] In the face of increasing expropriation of cultural property, the Ottoman Empire tightened regulations through the 1874 Antiquities Law, which replaced the previous law and was published in French and Turkish to ensure global understanding. This law was primarily aimed at foreign excavators and dealers and functioned more as a protection mechanism (Kersel 2008: 24).

A decade later, the Ottoman Law of 1884 established national ownership over all antiquities discovered on Ottoman soil. In addition to securing national patrimony the law also introduced regulations regarding excavation permits and taxes for the sale of antiquities. All artefacts discovered were to be sent to the Imperial Museum in Constantinople to be vetted prior to any decision. Chapter I Article 8 prohibited the export of all antiquities without the explicit consent of the Imperial Museum. However, this pushed the trade underground and established an intricate smuggling network throughout the region, which has persisted till present day (Kersel 2008: 24).

Indeed, practical enforcement of this law was difficult given the size of the empire and the insufficient number of officials to oversee the implementation of these rules. Furthermore, the law was easily circumvented through archaeological diplomacy (Pravilova 2014: 187). Ultimately, ‘state property’ meant that the antiquities were not the property of the state but of the sultan, who was able to trade for political loyalty and support (Ibid.: 187).

Following the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the British Mandate over Palestine was established by the League of Nations. The British were to be the temporary trustees of Palestine and were to ensure the protection of cultural heritage. In 1918, the government of the British Mandate declared the Antiquities Proclamation, which served to publicise the importance of cultural heritage and the need for its protection. This resulted in the archaeological sites acquiring ‘more professional and bureaucratic legal status’ rather than purely religious significance (Kersel 2008: 24). It was in this period that the Palestine Archaeological Museum was established from which the Department of Antiquities (DOA) operated.[3] John Garstang, Director of the DOA, used elements of the 1884 Ottoman Antiquities Law, to produce the 1920 Antiquity Ordinance. Similar to the Ottoman Law of 1884, it established national patrimony over all cultural property found in Palestine. Unlike the Ottoman laws, the legislation was to be overseen locally rather from the metropole. The 1920 Antiquity Ordinance defined antiquity as ‘any object or construction made by human agency earlier than A.D. 1700’ and it retracted some of the more unpopular properties of the Ottoman law, thereby legalising the sale of some material deemed duplicates of objects already in the national repository (Kersel 2008: 26). The result was a legal trade in antiquities, which was controlled by the DOA.

The 1920 Ordinance carefully regulated the trade in antiquities; dealers required a licence and their shops were to be inspected regularly. The Ordinance also introduced permits from the Department and taxes of 10% on exported antiquities. Failure to comply with the regulations was punishable as was ‘wilful or negligent destruction or defacement’ of the cultural heritage (Bentwich 1924: 253-254). The Ordinance, according to Bentwich, was successful because within four years a record of all archaeological sites and collections was completed and this enabled the foundation of a Palestine archaeological museum – “…so popular is this museum in Jerusalem that it is visited by not less than 1,000 visitors in a day. It has acquired, under the powers of the Legislature, the most notable objects, which have been unearthed in the diggings of the last four years” (Bentwich 1924: 254).

In 1929, another Antiquities Ordinance (No.51) was implemented. It forms the basis of all current legislation in Palestine and Israel and it specified the guidelines for dealing in antiquities. Dealers must apply for a license and provide an inventory list as well as submit to regular inspections by the DOA (Kersel 2008: 26). Following the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the Nakba, the 1929 Ordinance remained the primary legislation in place for cultural heritage protection. Indeed the Law and Administration Ordinance in 1948 reaffirmed the 1929 Ordinance as the primary legislation for the protection of cultural heritage. Similarly, in the West Bank the Jordanian Temporary Law no. 51 (1966) reiterated the same 1929 rules, except that the penalties for noncompliance were more severe. Since the 1967 war, the Israeli state has introduced a series of military orders in the occupied territories, which ultimately repeat the 1929 Ordinance but consign oversight to Israeli officials and not to the Palestinian Authority.[4] However, unlike the Ordinance, which required a permit for each artefact, the military orders require a ‘blanket export license’ (Kersel 2008: 28), which effectively relaxes the legislation. This could potentially provide the antiquities’ dealers in Israel with an ‘unending supply’ of artefacts (Kersel 2008: 29).[5]

The Israeli State formulated the 1978 Antiquity Law, and finally the 1989 Antiquities Authority Law, through which the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) was founded. This established the IAA as “the organization responsible for all the antiquities of the country, including underwater finds. The IAA is authorized to excavate, preserve, conserve and administrate antiquities when necessary.” However, despite these laws, illicitly excavated and acquired items are still being sold legally in the marketplace. This instinctively provides the incentive to loot archaeological sites. The result is that much is looted, and through a complicated process of laundering, it is resold from licensed dealers in Israel. A new law introduced in April 2012 was to eliminate these loopholes and better ‘prevent the importation … of antiquities that were stolen or plundered in other countries’ (IAA 2012). The law requires the dealers to report their inventories through an online programme, removing from the list the items sold so that identification numbers cannot be recycled for looted items. Previously, the recording of inventory was done manually and could thus be easily falsified, allowing dealers to claim that the items were acquired prior to 1978, when in reality they were looted much later. Ultimately, antiquity dealers operating in Israel have previously succeeded in exporting countless artefacts oversees and it is likely that in the near future additional cases such as the Hobby Lobby one will arise and thus the accomplishments of this new legislation remain to be seen.

Time line:

1835 Protection of Antiquities (Egypt)

1874 Antiquities Law (Ottoman Empire)

1884 Antiquities Law (Ottoman Empire)

1918 Antiquities Proclamation (British Mandate)

1920 Antiquities Ordinance (British Mandate)

1929 Antiquities Ordinance No. 51 (British Mandate)

1930 Antiquities Rules (British Mandate)

1966 Temporary Law no. 51 on Antiquities (Jordan)

1973 Military Order No. 462 (Gaza Strip)

1978 Antiquities Law (Israel)

1986 Military Order No. 1166 (The West Bank)

1989 Antiquities Law (Israel)

2012 Legislation on Antiquities Inventories (Israel)

Bibliography

Bentwich, Norman. 1924. “The Antiquities Law of Palestine.” Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law 6(4): 251-254.

Dunkow, Izabella. 2004. “The Ephesus Excavations 1863-1874, in the Light of the Ottoman Legislation on Antiquities.” Anatolian Studies 54(1): 109-117.

Field, Les, Watkins, Joe & Gnecco, Cristobal. 2016. Challenging the Dichotomy: The Licit and the Illicit in Archaeological and Heritage Discourses. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Friedlander, Marty. 2016. “Can You Buy Genuine Antiquities in Israel?” January 14. Haaretz.

Gopher, A. Greenberg, R. Herzog, Z. 2002 Archaeological Public Policy Public Policy in Israel. Perspectives and Practices. New York: Lexington Books.

Israel Antiquities Authority. 2012. “Israel Antiquities Authority Inspectors Seized Two Covers of Ancient Sarcophagi that Previously Contained Egyptian Mummies and were Smuggled into Israel.” March. Israel Antiquities Authority. Available on: http://www.antiquities.org.il/article_eng.aspx?sec_id=25&subj_id=240&id=1925 [Accessed on 1 October 2017]

Kersel, Morag. 2008. “The Trade in Palestinian Antiquities.” Jerusalem Quarterly 33(1): 21-38.

Pravilova, Ekaterina. 2014. A Public Empire: Property and the Quest for the Common Good in Imperial Russia. New Jersey: Princeton University Press

[1]As Marty Friedlander (2016) warns, this naturally leads to situations in which salesmen assure the potential buyer that the antiquity has ‘been sitting on the shelf of his shop since Menachem Begin entered office’.

[2]Izabella Dunkow (2004) suggests that this interest in antiquities was provoked by the visit of Sultan Abdülaziz to Europe in 1867 and encouraged by his visit to the Abraz Gallery in Vienna. Nevertheless, it seems likely that these regulations were a direct response to the expropriation of cultural property of national importance, for example, amongst other items, the Pergamon Altar. Ekaterina Pravilova (2014) argues that the first Ottoman law on the protection of antiquities occurred in Egypt (1835) and it prohibited the export of archaeological finds and made the protection of cultural heritage and monuments a royal obligation. This arose because the Ottoman military commander Muhammad Ali Pasha, the self-declared Khedive (viceroy) of Egypt in 1805 was using cultural heritage as foreign currency. He gave antiquities as gifts so that he was able to secure favourable relations with Europe. The Khedive was not officially recognised by the Ottoman Empire until 1867.

[3]The Palestine Archaeological Museum was seized by Israel following the Six Day War (1967) and was renamed the Rockefeller Museum. It remains under the management of the Israel Museum, despite its location in East Jerusalem.

[4]For example: 1973 Military Order No. 463 in Gaza forbade the exportation of antiquities from Gaza unless explicitly permitted by the director of the DOA and 1986 Military order No. 1166, ultimately repeated the legislation of the 1929 Ordinance but authorised an Israeli antiquities staff officer for the West Bank, who would oversee the implementation of the regulations and whose approval was required to export antiquities from the region.

[5]This ambiguity was later corrected in 2002 Chapter 4 Section 20 which states that: (a) A person may not bring into Israel an antiquity from the region, unless he has received approval to do so from the Director; (b) In this paragraph, “region” includes: Judea and Samaria [The West Bank] and the Gaza Strip.