For the Love of Museums

A visit to the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto, MArTA) reminded me why I love museums so much. It is an inspiring place, a valuable educational resource, and an underappreciated repository for art and heritage.

Taranto, Italy

Greek ruins (Temple of Poseidon)

MArTA is located in Taranto, a city located along the inside of the “heel” of Italy in the region of Puglia. It was founded by Spartans in 706 BC, and it became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia (the Roman-given name for the coastal areas in the south of Italy — Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily — heavily populated by Greek settlers). Two centuries after its founding, it was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of around 300,000 people. Taranto (called Tarentum by the Ancient Romans) was subject to a series of wars, culminating in its fall to Rome in 272 BC. The city fell to Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but was recaptured (and subsequently plundered) by Rome in 209 BC. The following centuries marked the city’s decline.

Cathedral of San Cataldo

Taranto’s mix of architecture and rich cultural heritage is due, in part, to subsequent changes in leadership between the 6th and 10th centuries AD, during which time it was ruled by diverse groups: Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Arabs. Later, during the Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century AD, the city served as a French naval base, but it was ultimately returned to the Kingdom of Two Sicilies for a few decades before it officially became part of the Republic of Italy in 1861.

Due to its strategic location on the inlet of the Gulf of Taranto, the city has great naval importance. Taranto served the Italian navy during both World Wars. As a result, it was heavily bombed by British forces in 1940 (the bombing of Taranto and was even noted to have “set the stage for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor” the following year). The city was also briefly occupied by British forces during WWII.

Evidence of the city’s various iterations is evident throughout its streets with impressive cultural sites, including the Greek Temple of Poseidon, the Spanish Castello Aragonese (built in 1496 for the then-king of Naples, Ferdinand II of Aragon), and the 11th century Cathedral of San Cataldo (Taranto Cathedral), where the remains of the city’s patron saint, Saint Catald, lie (he is believed to have protected the city against the bubonic plague). More recent architectural gems include Palazzo Galeota and Palazzo Brasini.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MArTA)

Like the city where it is located, MArTA is a rich institution full of incredible treasures. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit MArTA in person. Sadly, the museum, and the city itself, tend to fall under the radar of tourists. It is unfortunate that this site escapes attention, because both Taranto and its vaunted museum are incredible.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

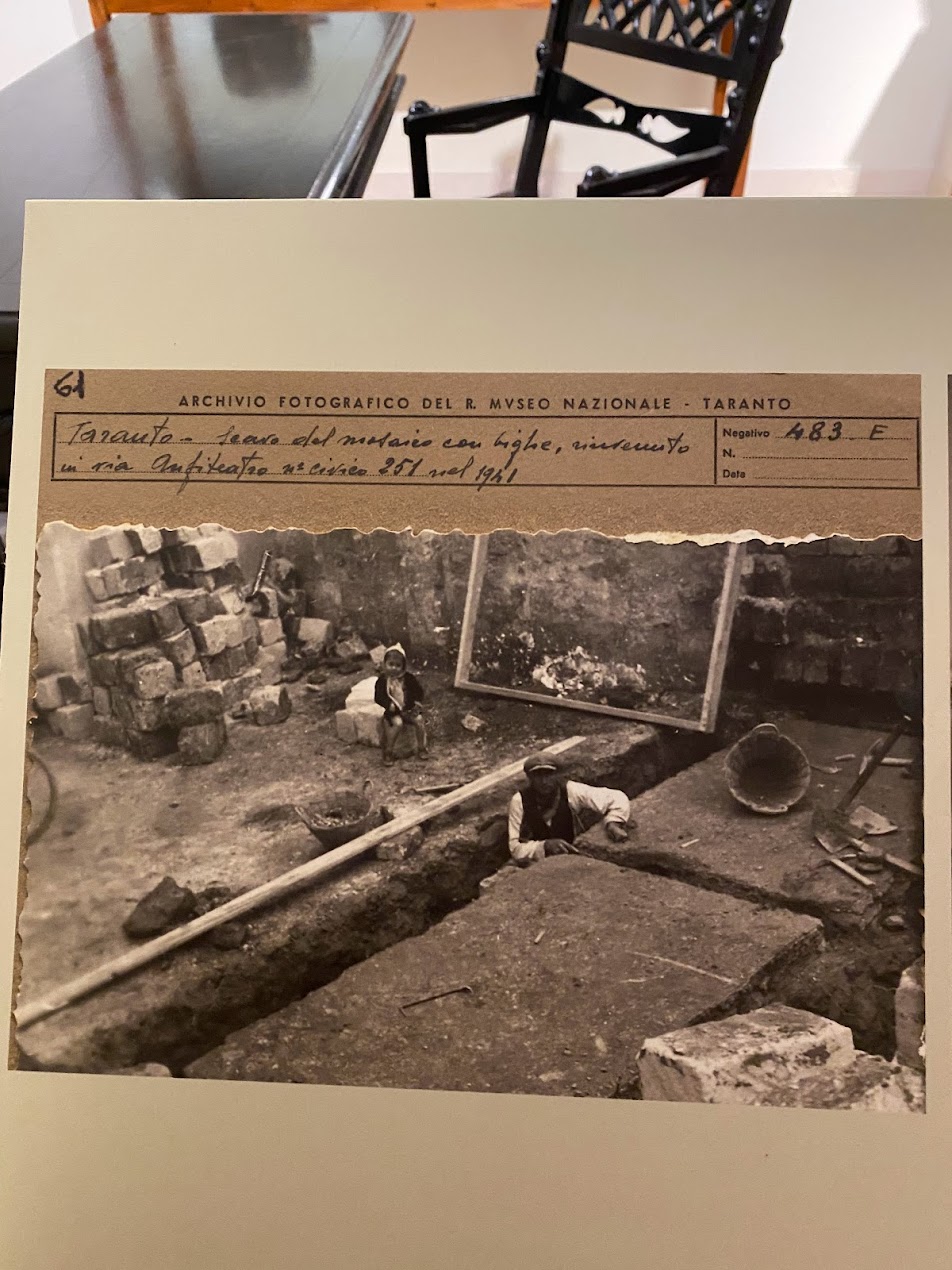

Amongst other treasures in MArTA are beautifully preserved mosaics, ornate golden jewelry, and ancient gold-covered snake skins. Another museum highlight are the informative displays positioning objects in creative contexts. For example, some objects are displayed along with photographic evidence and documentation about their excavation.

Tomb of the Athlete

The museum presents objects in beautiful vitrines. Some of the highlights on the first floor include thematic displays, such as a wall depicting Medusa’s face on antefixes found in Taranto. The curation includes information about the figure of Medusa in mythology and details on how her portrayal evolved over time. Another engaging display involves #italianmuseums4olympics, the Ministry of Culture’s campaign to support Italian sport and culture during the Olympic games. That particular display includes the sarcophagus of an athlete from Taranto, complete with amphorae found in his tomb that include images of athletic competitions, celebrating Italy’s long tradition of participating in the Olympics since antiquity.

An Apulian krater by the Darius painter returned from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2009

Looting of Objects on Display

As visitors enter the next floor of the museum’s route, they are confronted with a large restituted antiquity. A large Apulian krater by the Darius painter was returned to Italy in 2009 from the Cleveland Museum of Art after it was recovered by the Carabinieri’s TPC (the nation’s famed “Art Crime Squad”). The work was among fourteen artifacts returned from the Ohio museum after a two-year negotiation resulting from the investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici and Gianfranco Becchina, two well-known dealers of looted materials who sold antiquities at auction and through dealers to supply coveted objects to collectors and museums around the world.

Loutrophoros restituted by the J. Paul Getty Villa in Malibu in California

MArTA also acknowledges some of the people responsible for the development of its exquisite collection, including past directors and donors. The displays note that the illicit or unknown sale of antiquities has led to the loss of knowledge about their historical and cultural value (when artifacts are illicitly excavated and divorced from their contexts, valuable information is lost in the process). However, the development of patrimony laws has allowed the Italian government to control more of the archaeological discoveries taking place, and other legislation has also encouraged collectors to donate their property to the museum and Italian State. The display also notes the important work by law enforcement and its success in having works repatriated to Italy, as well as its success in confiscating looted artifacts from private owners and collectors during the 20th and 21st centuries in Italy. Part of this display features works returned from major museums abroad, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum in Malibu, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Labels and Information

The labels and information offered to visitors at the museum is exceptional, providing valuable information about the historic significance of items on display. Clearly, the museum places great importance on provenance, providing detailed information on where objects were excavated (this information includes exact find spots, with cross streets included for some of the objects), how they entered the museum’s collection, and ways in which the museum has evolved over the decades. Additional information is available to visitors about looting and criminal acts related to the objects, providing useful context.

Copy of the Goddess on Her Throne (the original is in Berlin)

One of the first objects to greet visitors upon their entry is a copy of a goddess on her throne. The original 5th century BC statue is “considered one of the greatest artworks from Magna Graecia.” It was found in 1912 in Taranto, but illegally exported out of Italy. It was then put on the Swiss art market, and finally purchased by the German government. It is currently on display at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Information like this is valuable, because it forces visitors to confront the political, societal, and cultural pressures facing museums, as well as the challenges and realities of the art and antiquities markets. It also provides a practical example of how works can wind up in international museums divorced from their original historical and cultural context.

As the museum’s website states, “The Museum also lends artefacts to other museums to allow global citizens to enjoy. We are aimed at providing first-hand information to all of our visitors so that they understand Europe’s prehistoric period.”

Castello Aragonese

A visit to this museum, and the gorgeous city of Taranto, with its sweeping coastal views, its rich cultural history, and its stunning architectural masterpieces, is essential for anyone visiting Puglia.

Copyrights in all photographs in this post belong to Leila Amineddoleh

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Objects from the museum’s early collection

Documentation of excavations

Vitrine (provenance information for each object is provided in a side panel)

Provenance on view

Beautiful entryways on each floor

Context with a photograph

On September 22, Matthew Bogdanos submitted an application in NY Supreme Court in a matter involving a stolen antiquity from Lebanon. Our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert on this case. It was an honor to once again work with Bogdanos, a talented trial attorney. His track record for excellence is impressive, and the filing in this case is a tour de force of legal writing, reading like a suspenseful crime narrative and primer on cultural heritage law. The document was full of famous art world names, citations to landmark cases and conventions, and introduction to the world of art crime and heritage looting.

On September 22, Matthew Bogdanos submitted an application in NY Supreme Court in a matter involving a stolen antiquity from Lebanon. Our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert on this case. It was an honor to once again work with Bogdanos, a talented trial attorney. His track record for excellence is impressive, and the filing in this case is a tour de force of legal writing, reading like a suspenseful crime narrative and primer on cultural heritage law. The document was full of famous art world names, citations to landmark cases and conventions, and introduction to the world of art crime and heritage looting.