by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Mar 23, 2024 |

In a highly-public withdrawal, Christie’s pulled four ancient Greek vases from auction. The four antiquities ranged in value from $7,000 to $30,000. It appears that the vases are the product of illicit dealings. They have been traced to the notorious antiquities trafficker Gianfranco Becchina.

One of the four disputed vases pulled from auction. Image via Christie’s.

Vases Traced to Notorious Dealer

Becchina, a well-known middleman in a looting network who was convicted for his actions in 2011, cosigned three of the four vases for a Geneva Christie’s auction in 1979. For the upcoming April 2024 auction, Christie’s listed the vases’ sale in 1979, but failed to disclose the fact that Becchina cosigned the objects. Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis, a lecturer at the Unviersity of Cambridge, called Christie’s nondisclosure “a trick used by the highest level. . . [t]hey deliberately exclude the connection of a trafficker in these three examples, although they’ve known about that connection for 45 years.”

Christie’s has released a statement counter to this effect, stating that the auction house “takes the subject of provenance research very seriously, especially when it related to cultural property.” However, taking the subject of provenance research seriously, and proactively allocating the resources and dedicated staff to carry out the work, are two different things.

A disputed vase pulled from auction. Image via Christie’s.

New Head of Provenance at the Met

In other antiquities news, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is taking a proactive stance. Last month, the museum hired Lucian Simmons (previously of Sotheby’s) as its first-ever Head of Provenance Research. This new position points to the museum’s recent efforts to increase the museum’s number of provenance-specific employees, in an era of greater scrutiny against both private and public collections. An increase in the number of restitutions has occurred during the past few decades, and this new hire makes the Met better situated to research provenance issues and handle requests for restitution. Mr. Simmons’ hiring brings the number of specialized province employees to eleven – an astonishing number for the institution.

Mr. Lucian Simmons. Image via Wilson Santiago/Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mr. Simmons has extensive experience with provenance research and related issues, due to his long tenure at Sotheby’s. Since 1997, Simmons has developed and deployed transparent provenance policies for the auction house. In fact, transparency is at the heart of all of Simmons’ provenance work. He told to The New York Times that from the beginning of his time at Sotheby’s, he has “always tried to make sure [Sotheby’s was] very open” in the provenance research processes. Simmons intends to continue innovative model of transparency when he transitions to the Met this coming May.

New Awareness for Repatriation of Looted Antiquities

Repatriation actions for looted antiquities are increasingly being brought by countries around the world. Our firm has proudly represented and won legal claims related to looted antiquities on behalf of several nations, including the Republic of Italy and the Hellenic Republic of Greece. The cultural shift towards an increased awareness and respect for repatriation and restitution claims is something our firm both applauds and works to uphold.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 27, 2023 |

Roman Forum. Image via Fodor’s, available at https://www.fodors.com/world/europe/italy/rome/experiences/news/photos/the-10-best-ancient-sites-in-rome.

Our firm is pleased to continue our collaboration with the American Institute for Roman Culture (AIRC) in their Ancient Rome Live Series. Those familiar with the AIRC’s work will remember our firm’s past contributions to the series, which are available here.

For those who are just learning of AIRC and their work, the AIRC is an internationally-acclaimed non-profit founded in 2002 to promote Italian culture. AIRC provides opportunities for education, archeology, and study abroad, with locations in both the U.S. and Italy. AIRC’s founder, Darius A. Arya, is an archeologist, public historian, author, social media influencer, and TV host based in Rome, Italy. In his role as AIRC CEO, Dr. Arya leads lecture series, heritage preservation initiatives, teaches bespoke educational courses, and hosts a highly-rated podcast called Darius Arya Digs.

Colosseum. Image via Fodor’s, available at https://www.fodors.com..

Our firm’s most recent contribution tackles the complicated (and extremely timely) issue of overtourism. Following the opening of international borders, tourists have flocked to cultural heritage hotspots around the globe. The sudden influx of tourism to cultural heritage sites seems to be a symptom of “revenge tourism,” the product of isolating at home during the pandemic. While re-engaging with travel in a thoughtful way no doubt fuels local economies and broadens the mind, thoughtless travel often results in the destruction of priceless pieces of cultural heritage.

Interested? Read the entire article on the Ancient Rome Live Series website, here.

AIRC has been an awarded an NEH grant, an American Express Foundation grant, and a World Monuments Fund (WMF) collaboration. AIRC receives additional funding from anonymous angel investors and individual donors. If you would like to contribute to AIRC and Dr. Arya’s world-class courses and promote opportunities for lifelong learning, you may support the organization here.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jun 27, 2023 |

We are thrilled to announce the newest publication from associate Maria T. Cannon. Her latest article, “The Need for Speed: Why Recovery of Missing Art Needs an Upgrade,” was published in the ABA’s Art & Cultural Heritage Law Newsletter, Spring 2023 Edition.

The Dutch Room with empty frame at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, site of the most notorious art theft in modern history (2016). Image via

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo Credit: Sean Dungan.

The piece discusses a new take on art crime and looting. She highlights how recovering artwork is a race against time. Art, once stolen, is uniquely difficult to find. Moreover, because stolen art is often delicate, it is subject to physical deterioration. Legal channels to recover artwork often slow down the process. Another issue can come from law enforcement. To recover major stolen works of art, the U.S. often relies on FBI agencies that lack crucial insider knowledge of local crime organizations. She acknowledges these difficulties, an offers creative solutions.

Want to read Maria’s article? Contact the ABA Art & Cultural Heritage Law Committee for a full copy of this season’s great newsletter.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 4, 2022 |

The following guest blog post was written by Andrea Martín Alacid.

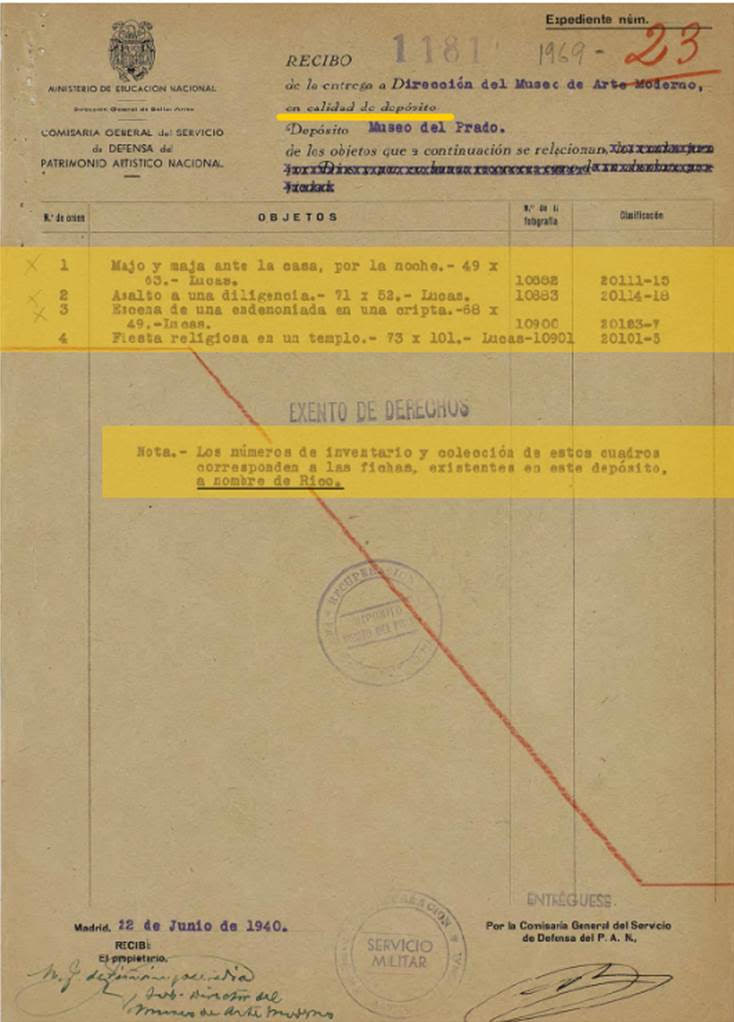

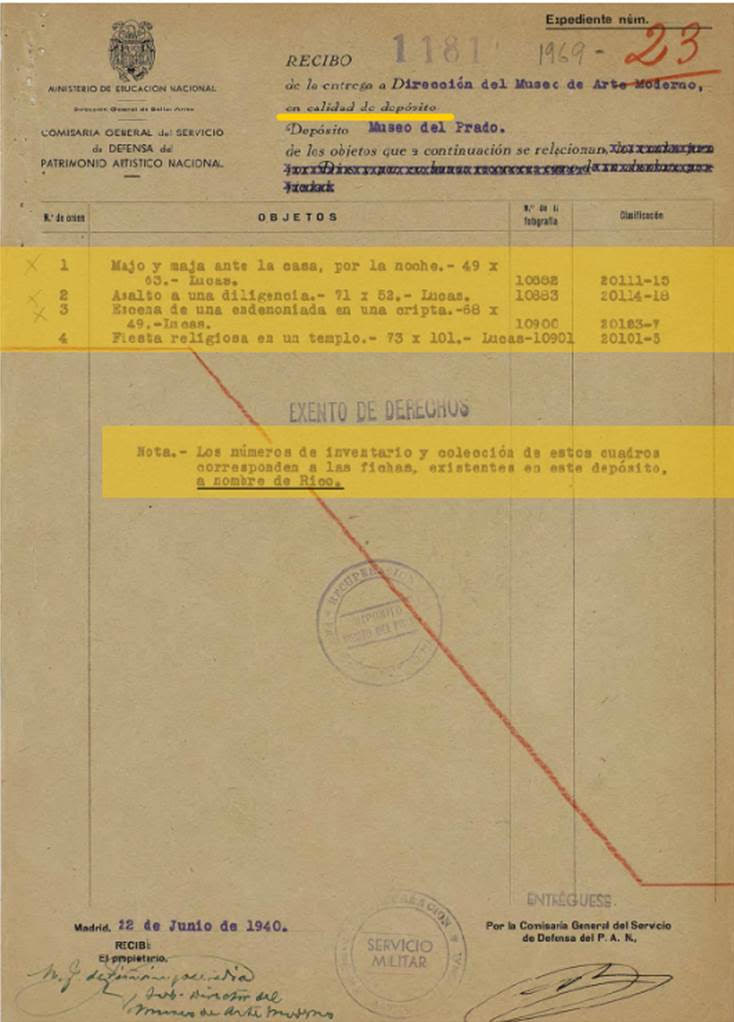

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase.

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase.

In response, the Prado has commissioned Professor Emeritus Arturo Colorado Castellary to lead a research project at the museum with the aim of clarifying the provenance of some of its works. His research will examine the background and context in which the works entered the Prado’s collections, in order to promote transparency and (if necessary and in compliance with all legal requirements) return them to their rightful owners. Professor Colorado is expected to share the first results of his research in early 2023.

Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm Caliope Art Law Boutique, founded by Laura Sánchez Gaona, to set forth their claim.

Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm Caliope Art Law Boutique, founded by Laura Sánchez Gaona, to set forth their claim.

As a result of the research carried out by the due diligence department of the law firm, along with the information provided by the Spanish General Directorate of Fine Arts, led by Isaac Sastre de Diego, the current location of 23 of the family’s artworks in various Spanish museums was discovered. In September 2021, members of the Caliope Art Law Boutique accompanied one of the heirs to identify the three Eugenio Lucas paintings in the custody of the Prado. The heirs had previously never seen these works in person. Although this was just a first step, it was an emotional moment for all those present, including Andrés Úbeda de los Cobos (Deputy Director of Conservation and Research) and Carlos Chaguaceda (Director of Communications) working on behalf of the Prado. While viewing the three paintings, it was noted that the Prado kept the Seizure Board’s labels intact. This is most valuable as the label recorded the name of the works’ rightful owner, Pedro Rico.

The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

In short, there is no doubt that this initiative by the Prado, together with the re-evaluation of adverse possession, is a crucial and significant step in the restitution procedures of looted cultural heritage in Spain, which unfortunately lack a specific legal framework at this time. It is likely that this framework will be developed in the near future, and we eagerly await ongoing developments.

We congratulate our esteemed colleagues and friends in Spain for their remarkable work fighting for justice and paving the way for equitable restitutions in Europe.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 15, 2022 |

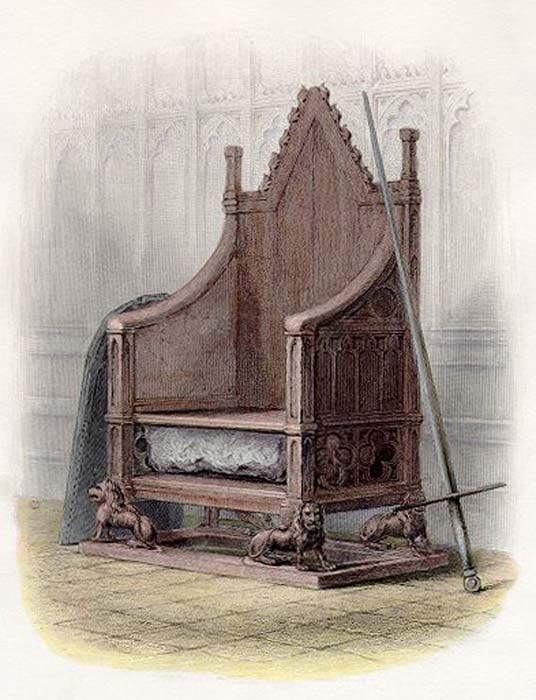

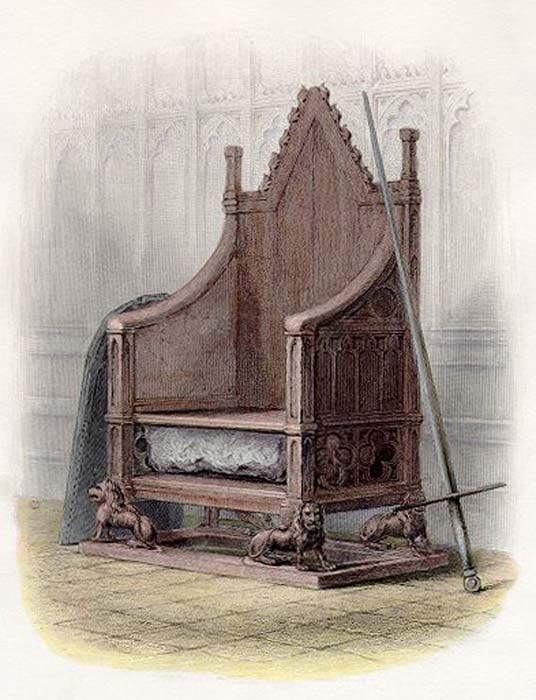

The Stone of Scone in Westminster Abbey

Last week’s passing of the cultural and political icon, Queen Elizabeth II, marks the end of an era, as well as the beginning of a new reign for her son, King Charles III. While the King’s coronation is a long way off (likely to take place in 2023), preparations for the events are already underway. Centuries-old traditions are being planned to punctuate the big day, including the assemblage of one of the globe’s most exclusive guest lists. And the most important guest on that list is an enormous slab of rock. Not to be confused with The Rock, the Stone of Scone is an ancient Scottish artifact. And it is what it sounds like – a large, grey stone – and its presence at the coronation is nearly as essential as His Majesty’s.

Edward Longshanks (portrayed in Braveheart). Copyright: 20th Century Fox Film Corp

Originally used as a throne by the ancient Scots to crown their rulers, the Stone was stolen by King Edward I during the Scottish Wars of Independence in the late 13th century. In stealing the Stone, King Edward sought to send a message to the Scots by establishing himself as their rightful monarch. Unbeknownst to Edward, the Scottish people did not intend for such pillaging to go unpunished, even if the retaliation did not take place until centuries in the future.

In 1950, four unlikely heroes – a motley group of students, led by ringleader Ian Hamilton – snatched the Stone from its place in the Chapel in Westminster Abbey. The quartet then literally carted the antiquity back to Scotland in not one – but two (more on that below) – Ford Anglias. The heist – though ultimately successful – did not occur without a hitch (hence, the two Fords). During the dislodging of the Stone from King Edward’s Chair in King Edward’s tomb, the Stone somehow slipped and smashed to the floor, breaking into two pieces. Not to be deterred, the foursome quickly bundled up the Stone in two packages. One piece was placed in Ford #1, which set off for home. The second piece was tucked into the trunk of Ford #2, driven by our ringleader, Hamilton.

Unfortunately for Hamilton, the night’s struggles were not quite complete, and as dawn broke over the horizon, a policeman approached the car, curious as to why two students were quickly and nervously dashing away from the Abbey at 5am. Hamilton and his fellow passenger jumped into a feigned lover’s embrace, and, after swapping a few innuendos with the policeman, were sent happily on their way.

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the Arbroath Abbey in Scotland. This is where the Stone remained until 1952, when it was returned to Westminster Abbey in England.

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the Arbroath Abbey in Scotland. This is where the Stone remained until 1952, when it was returned to Westminster Abbey in England.

And what about our “bravehearted” student thieves? They were eventually questioned by the authorities, leading Hamilton to confess the entire episode. However, none of the students faced prosecution for their theft, due to the incredible political implications of the heist and the ensuing renewed vigor for Scottish nationalism and devolution efforts.

The 1950 theft became both infamous and synonymous with a separate and distinct Scottish identity, as essentially a testament in itself to the history of independent Scottish reign. In fact, the theft became so closely associated with Scottish independence that England’s return of the Stone to Scotland in 1996 is believed to have been a catalyst for the vote for Scottish devolution in 1997.

Today, the Stone remains in Scotland and travels to England only for the coronation of a new British monarch. As the Stone comes back into the global zeitgeist due to the preparations for England’s crowning of a new King, the Stone’s cultural, political, and historical significance cannot be overlooked. The Stone – and its rare journey between the two Abbeys – encompasses the history of the Scottish monarchy, the legitimacy of British rule, the enduring spirit of Scottish cultural identity, and the undercurrent of thievery and war.

Our thoughts are with the Royal Family and all citizens of the United Kingdom during this time of mourning.

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase.

Following other European museums such as the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, Museo Nacional del Prado (the Prado) in Madrid recently announced a new initiative. It would carry out an ex officio review of its collection to identify works of art seized during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s regime by the Board of Seizure and Protection of Artistic Heritage founded in 1936 (and known as the Board of Artistic Treasure from 1937 onwards). Following the museum’s initiative, 25 documented works that were never returned to their rightful owners have been identified so far, but there is no doubt that this number could increase. Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm

Following the Prado’s announcement and after a great deal of research, this initiative has already borne fruit. The heirs of Pedro Rico López (a lawyer and Republican politician, as well as the mayor of Madrid in the 1930s), have begun the restitution process for the at least 25 paintings thus far. It was not until February 2021 that López’s grandchildren first learned about the whereabouts of their family’s artworks. The works were seized during the post-war period. The heirs eventually learned of the seized assets from an article, El botín del patrimonio español que el franquismo repartió en la posguerra (The spoils of Spanish heritage that Franco´s regime distributed in the post-war period), published in the Spanish national newspaper ABC, after Arturo Colorado’s research came to light . The heirs retained Spanish art law firm  The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

The paintings currently held by the Prado, together with the other works documented, have been in the possession of different administrations for a number of decades. Under the law of adverse possession in the Spanish Civil Code, the museums are considered the legal owners. However, the State Attorney General’s Office has recently reevaluated this doctrine in the context of plundered works of art. As a result, the first restitution of a work of art seized during the Civil War took place last month. The recipients are the family of Ramón de la Sota Chalbaud, and the work in question is Portrait of a Young Gentleman by Cornelis can der Voort. This landmark restitution has paved the way for new cases to come.

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the

This resolved the exit part of the theft, yet left unresolved the issue with the Stone being smashed into two pieces. Upon arrival in Scotland, the Stone received some TLC and a professional mending by a stonemason, who, in addition to doing fantastic masonry, was also phenomenal at keeping secrets. The mason fixed the Stone and breathed not a word to the authorities. But several months later, police received a call about the whereabouts of the Stone: it had been deposited in the