Amineddoleh & Associates Quoted in the Washington Post

Our founder, Leila, was quoted in the Washington Post, discussing the challenges facing nations making demands for the repatriation of stolen cultural heritage. Read the article HERE.

Our founder, Leila, was quoted in the Washington Post, discussing the challenges facing nations making demands for the repatriation of stolen cultural heritage. Read the article HERE.

Museo dell’Arte Salvata (Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh)

Amineddoleh & Associates LLC is proud to work as a leading law firm in the cultural heritage sector. We have worked with collectors, dealers, museums, law enforcement agencies, and even foreign governments. One of our clients is the Republic of Italy, a nation paradoxically blessed with an abundance of artistic and cultural treasures, but cursed with the solemn responsibility of protecting those treasures. Properly monitoring antiquities and archaeological sites, regulating the market, and protecting cultural heritage is a costly and heavy burden. Every region of the Italian nation is famed worldwide for its cultural treasures, and so the country has developed means to actively protect its heritage through various channels. For instance, Italy is the first nation in the world to have a military unit responsible for the protection of art and heritage.

The Carabinieri Headquarters for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, or TPC) was instituted in 1969. The TPC is a part of the Ministry of Culture and plays an important role regarding the safety and protection of the heritage. The TPC is renowned for its efforts and works with law enforcement agencies around the world to recover stolen and illicitly exported artifacts, assists in heritage protection and management globally, recovers stolen art within Italy and abroad, and works to monitor and regulate the art market for looted or illicitly removed art and antiquities.

The TPC has had tremendous success over the decades, recovering hundreds of thousands of objects worth billions of dollars. In a thrilling recent escapade during 2020, the TPC tracked down a 500-year-old painting stolen from a museum in Naples. Jesus Christ in his “Savior of the World” (Salvator Mundi) aspect. The work is a copy of the infamous Salvator Mundi that sold for over $450 million in 2017 (considered the world’s highest-selling painting to date). The police found this copy stashed in the cupboard of an apartment and arrested the 36-year-old property owner. It was probably easy to spot among the inhabitant’s mismatched cutlery.

Castel Sant’Angelo (Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh)

The elite and highly specialized force has celebrated its successes in countless repatriation ceremonies and with art exhibitions. In particular, 2009 marked one of the most high-profile returns resulting from TPC investigations. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (the “Met”) returned the Euphronios Krater (infamously known as the “Hot Pot”) to Italy once the TPC and Swiss authorities uncovered an extensive looting network selling black market antiquities from Italy. These objects wound up in the hands of reputable collectors and museums, including the Met, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum, Harvard University, and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In the wake of this return, hundreds of other items from that network were returned. These restituted works were exhibited in the Colosseum with much pomp, circumstance, and celebration.

At the United Nations in January 2020

A decade later, in 2019, in honor of the TPC’s 50 anniversary, the Carabinieri, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, and the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities organized a comprehensive exhibition of recovered art. “Recovered Treasures: the Art of Saving Art” was on view in Paris and then displayed at the United Nations in New York in January 2020. Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, was invited to attend this exclusive event to open this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition. At the opening, Secretary-General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres aptly stated that the “exhibition not only comprises priceless works of art, it also paints a picture of the power of international cooperation.”

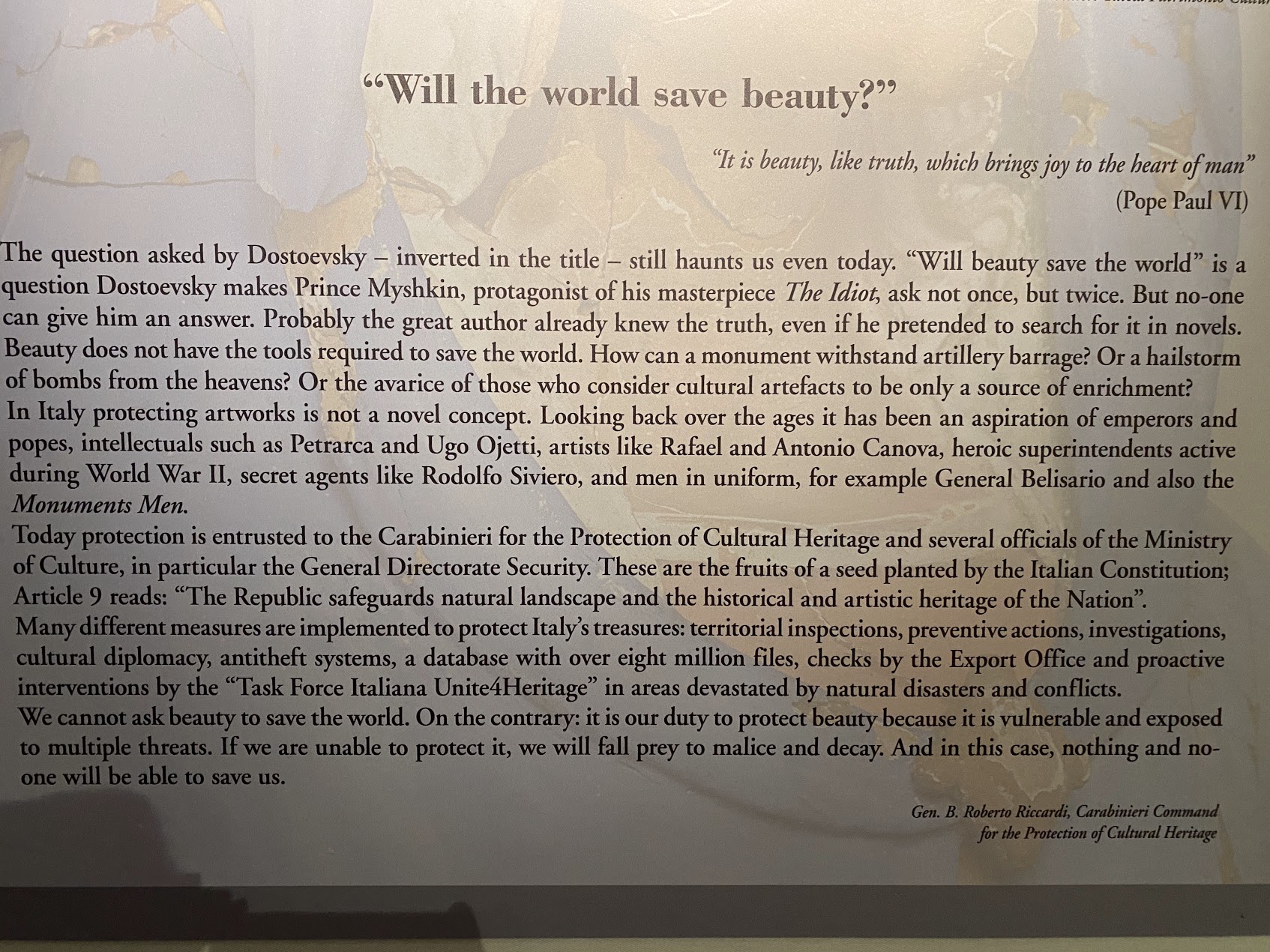

Sign at the entry of “Will the world save beauty?” exhibition

When Italian museums finally reopened after the Covid pandemic, the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome hosted an exhibition entitled “Will the World Save Beauty?,” a show dedicated to exhibited repatriated antiquities, items recovered after natural disasters, works stolen from churches and private institutions, the prevalence of forgeries, and even stolen instruments. Leila also received an invitation from the Carabinieri to view this jaw-dropping show. The juxtaposition of recovered antiquities in a building with nearly 2,000 years of history was both ethereal and moving. This historic site had survived sacking and plundering, and so it was particularly effective to experience repatriated artwork in such a historically rich setting.

Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh

At the start of this summer, Minister of Culture Dario Franceschini announced the opening of the Museo dell’Arte Salvata (“Museum for Rescued Art”), a new museum displaying looted works returned to the Mediterranean nation. The concept for this museum is innovative and appealing – hundreds of smuggled, and now repatriated, artworks will be displayed for public view. But the particular items on display will rotate, with the next group of pieces to be presented after October 15, 2022. Once the displayed works are removed, they will be returned to the respective regions of Italy from where they were originally stolen. The museum’s noble aim is to return objects to the collections of small museums that have suffered from the loss of artwork, giving them and the nation of Italy as a whole a boost to aid in post-pandemic recovery for the culture sector.

Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh

Our founder had the pleasure of visiting the museum shortly after its fabulous opening. The museum is intimate (the objects are all displayed in one large room), and the exhibition is excellent. The repatriated objects on display are organized in glass vitrines featuring information about the works’ significance, the ways in which they were smuggled, and the importance of repatriation. The museum notes that the objects on display are “mainly from the United States of America.” The United States (in particular, New York) is the center of the art market and so items are sold both legally on the market and illicitly. But US authorities have also been instrumental in recovering stolen and illicitly exported objects linked to Italy.

Franceschini stated: “Stolen works of art and archaeological relics that are dispersed, sold or exported illegally is a significant loss for the cultural heritage of the country…. Protecting and promoting these treasures is an institutional duty, but also a moral commitment: it is necessary to take on this responsibility for future generations.” Stéphane Verger, director of the National Roman Museum, poignantly noted: “I think of this as a museum of wounded art, because the works exhibited here have been deprived of their contexts of discovery and belonging.”

Just a month after this exhibition’s opening, another 142 Italian antiquities seized by the Manhattan DA are headed home to Italy. This included 48 items recovered from private collector Michael Steinhardt during a high-profile seizure in December 2021, where the former hedge fund manager agreed to surrender $70 million worth of antiquities. The most valuable work returned to Italy is a fresco depicting an infant Hercules strangling a snake, valued at $1 million and looted from Herculaneum. Officials revealed that another 60 of the items were recovered from Royal-Athena Galleries in Manhattan.

Copyright: Leila A. Amineddoleh

As this law firm is currently representing the Republic of Italy in an ongoing antiquities dispute, and our founder served as a cultural heritage law expert for the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office regarding the seizure of items from Michael Steinhardt, traveling to Rome and visiting such an impressive and important exhibition was – in Ms. Amineddoleh’s word – both powerful and gratifying. This highlights the impact of cultural heritage looting and trafficking at the global level and close to home.

The Museo dell’Arte Salvata is located in the Aula Ottagona, a building that had previously been closed for a number of years. The structure is part of the Baths of Diocletian complex, located a few minutes away from Termini Train Station (Rome’s main railway station), and across the street from the Repubblica subway station, in the heart of the Eternal City. Since it is part of the network of national Roman museums, visitors can purchase one ticket and see all five museums for one relatively inexpensive entry price. It is well worth the trip – and visitors can wrap up their visit with a large bowl of cacio e pepe and a hearty glass of Chianti Classico for a true Italian experience.

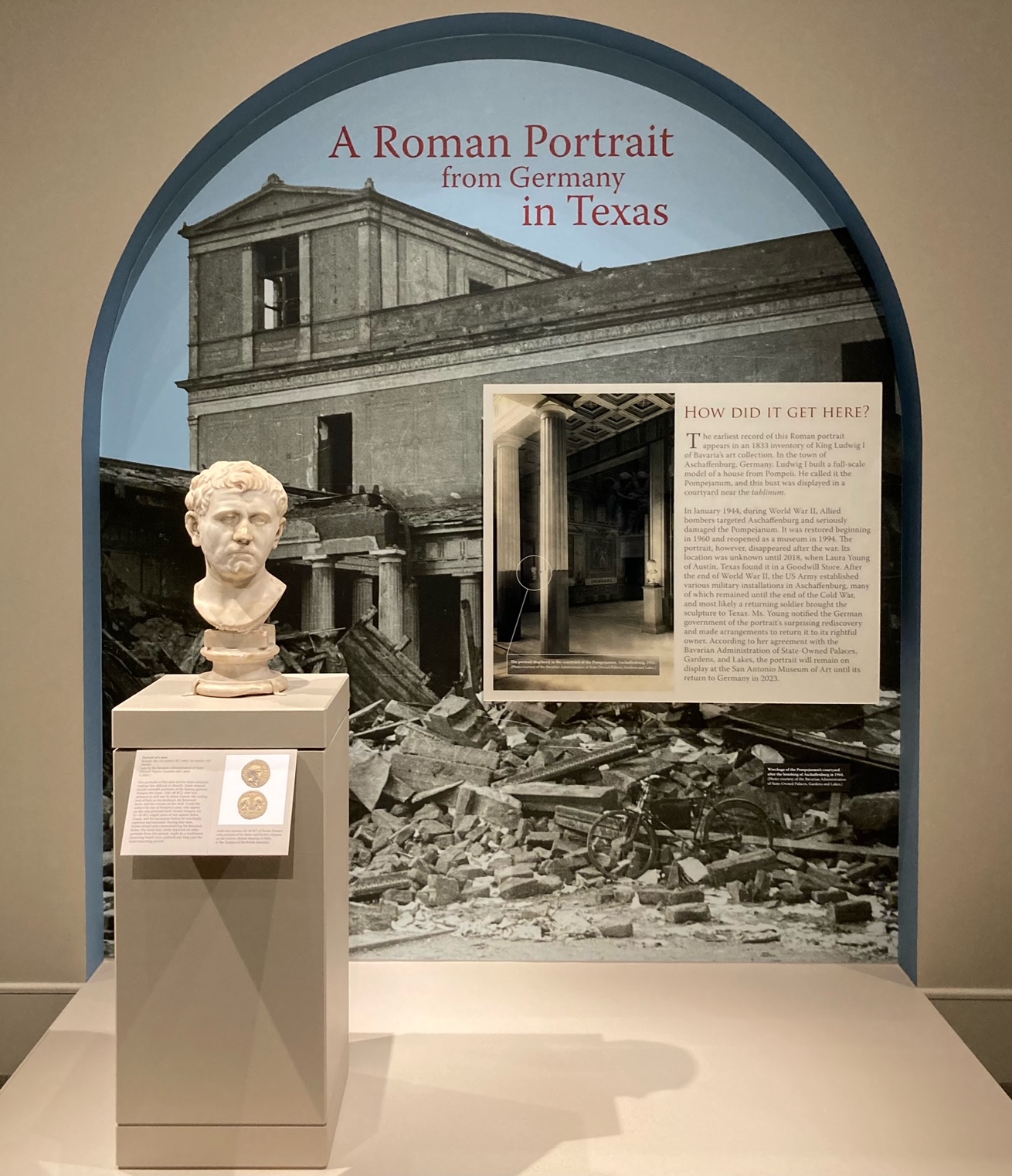

The Marble Bust found in Texas that will be returned to Germany

Amineddoleh & Associates is proud to announce its role in a recent antiquities matter, whereby a Roman marble bust looted during WWII will be restituted to the Bavarian government in Germany. Below, we share details about the bust’s provenance, examples of other cultural objects looted during World War II, the vital work by experts in establishing provenance, and our role in this important cultural return.

Much of the literature about WWII-era looted art focuses on thefts perpetrated by the Nazi Party. The Nazis pillaged on a continental scale – appropriating about 20% of all art in Europe at the time. They were notorious for confiscating artworks they deemed “degenerate,” although other works of art were also swept up in their violent mass seizures. One example is the extensive Czartoryski family collection from Poland, which included Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci (later recovered) and a portrait of a young man by Raphael (still missing). After the occupation of Paris in 1940, over 20,000 looted works were taken to the Jeu de Paume gallery, and were kept in a place known as “The Room of the Martyrs.” While Hitler and high-ranking officials had first pick of the loot, German officers could later select masterpieces of their choice. The remainder were slated for destruction, but some evaded this fate thanks to the efforts of art historians and the famed Monuments Men (this title is a misnomer, as this group of British and American members included women).

Looting is often a crime of opportunity, and soldiers on all sides of a conflict may take advantage of the situation by partaking in the appropriation of stolen valuables. Allied soldiers during WWII were no exception. Some of the goods pilfered by Allied troops, like cigarettes and household goods, are relatively inexpensive or nearly worthless by today’s standards. But others – including paintings, rare coins, historic photos, musical instruments, and antiquities – possess great artistic and cultural value. Those valuables continue to be found to this day, sometimes in surprising locations. Some have been returned to the heirs of the original owners while others are involved in ongoing litigation.

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer

In one instance, a member of the U.S. Army stole a collection of medieval religious objects that had been hidden in a cave for safekeeping during the war. The soldier mailed these priceless artifacts home to his family in Texas. These items, known as the Quedlinburg Treasure, included a jeweled 9th-century manuscript written entirely in gold (the Samuhel Gospel). Decades later, the soldier’s heirs reached an agreement with Germany and returned the items in exchange for $2.75 million. Another case involved a pair of portraits by Albrecht Dürer stolen from a museum in East Germany during the war. These were taken by an American serviceman and later bought by a New York collector, Edward Elicofon, for $450. Although Elicofon was purportedly unaware of the paintings’ provenance, a friend recognized the works from a book on art stolen during WWII. After the museum filed a lawsuit in New York, the court compelled Elicofon to transfer ownership and possession of the works back to Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar (Weimar Art Collection).

Perhaps the best-known case involves Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as the Woman in Gold. This gilded painting was forcibly seized by the Nazis after the owners, a Jewish family, were forced to flee Austria in fear of their lives. The portrait is called “the Mona Lisa of Austria.” Along with other works from the Bloch-Bauer’s collection, the portrait wound up in the Austrian State Gallery, but the heirs to the estate fought to recover their family’s lost property. Eventually, after litigation in the U.S. and arbitration in Austria, the Bloch-Bauer heirs succeeded. The dramatic tale became the subject of a film starring Helen Mirren as the main claimant, Maria Altmann, and the painting was later sold in 2006 for $135 million – a record price at the time.

Not all art and heritage restitutions involve contentious battles. The most recent example of a voluntary return of valuable WWII-looted art can be found in the just-announced agreement between Germany and our client, Laura Young.

The Marble Bust safely strapped in Ms. Young’s car with a seatbelt

Ms. Young happened upon the Marble Bust in the unlikeliest of places: a goodwill thrift shop near her home in Austin, Texas. She purchased the artifact and immediately realized it was more than it appeared to be. The 52-pound Marble Bust, standing at 19 inches tall, was in fact an extremely valuable antiquity. After she drove the Marble Bust home (responsibly strapped into her car with a seatbelt), Ms. Young began digging into its past and discovered the remarkable nature of her find.

Ms. Young later confirmed that, unbeknownst to the goodwill thrift shop owner, the Marble Bust depicts famed Roman commander Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, known simply as Drusus Germanicus or Drusus the Elder. She went on to discover that the Marble Bust has a significant provenance, including links to royalty.

To truly appreciate the richness of the Marble Bust’s provenance, a bit of history is required.

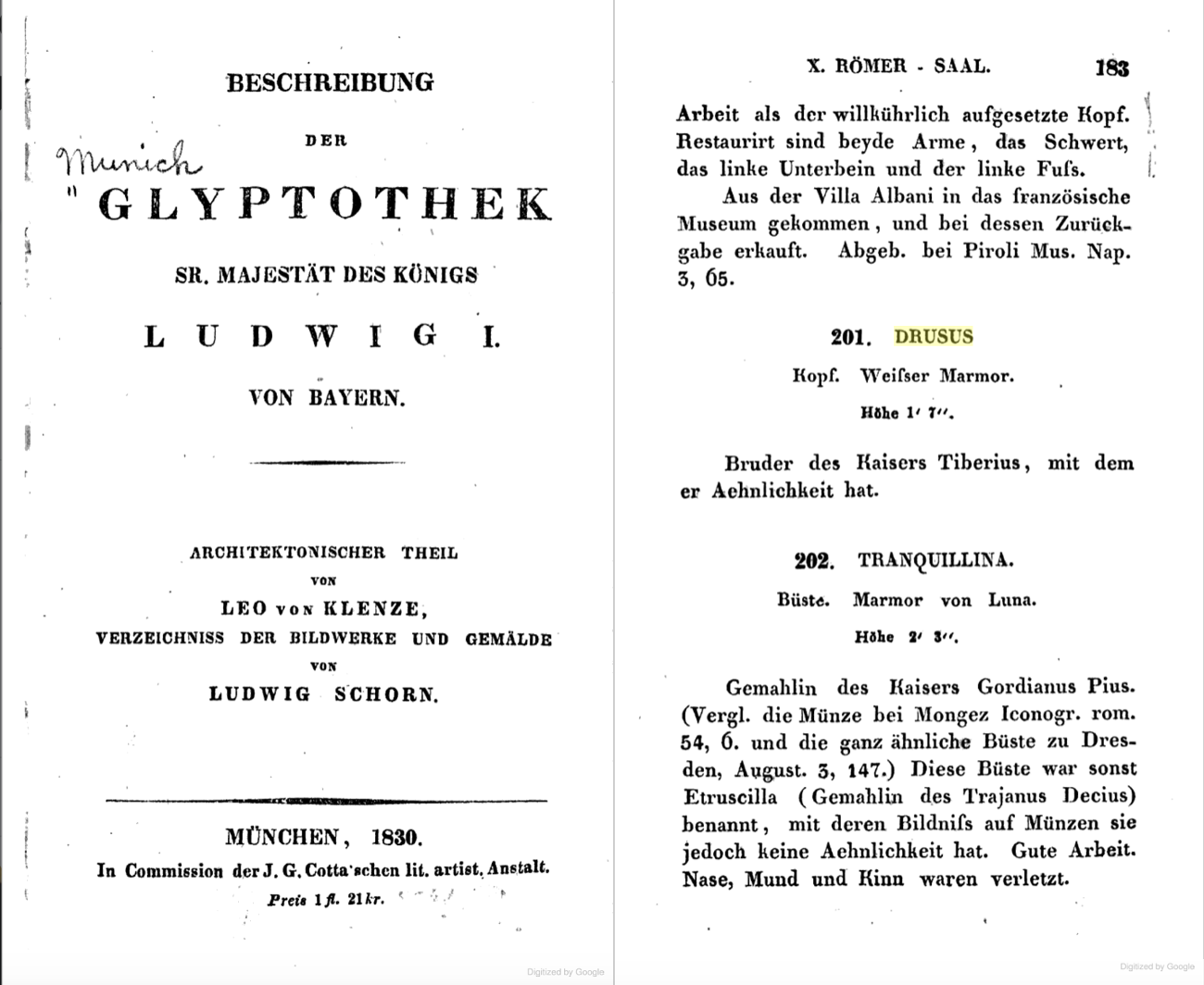

Left, cover of 1833 catalog of King Ludwig I’s antiquities collection , right, description of Drusus (the Marble Head) listed in the catalog

Image from google books digitized version of the catalog

Born on January 14, 38 B.C. to Livia Drusilla and Tiberius Claudius Nero, Drusus Germanicus was the legal stepson of Livia’s second husband, Octavian (later Emperor Augustus and great-nephew of Julius Caesar). Drusus was born shortly after his mother’s divorce, and his mother immediately married Octavian, who historians suspect was Drusus’ true father. Drusus Germanicus eventually became the commander of the Roman forces occupying the German territory between the Rhine and Elbe Rivers. In 9 B.C., Drusus reached the Elbe River, but he was thrown from his horse and died 30 days later from the injuries he sustained. For his conquest of Germania, he received the posthumous honorific title “Germanicus.” The Marble Bust of Drusus Germanicus traveled to Germany nearly two millennia later after its acquisition by the King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, at some point prior to 1833.

Although Drusus was lesser known than some other members of his family, portrait heads of this figure are rare (perhaps due to Drusus’ early death) and highly prized.

After its acquisition by Ludwig I, the Marble Bust was transferred to a most fitting location – the Pompejanum. The Pompejanum (or Pompeiianum) is a replica of a Roman townhouse in Pompeii. Overlooking the Main River in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg, the museum was already a popular tourist destination in the 19th century. The Pompejanum was commissioned by Ludwig I, who was inspired, like many cultural enthusiasts, by the excavations at Pompeii.

Ludwig I was both an art lover and a great patron of the arts. During his reign from 1825 through 1848, he commissioned major museums and art projects throughout Bavaria and the rest of Germany in a bid to elevate Munich to the status of rival European art capitals, like Rome and Paris.

His passion for art was first awakened on a trip to Italy from 1804 to 1805. After that trip, the future king became a voracious collector. Much like today’s collectors, he sent agents across Europe to acquire masterpieces. (One of his art dealers, Johann Martin von Wagner, was noted for his unerring eye, scholarly talent, and great commercial aptitude.) With an unlimited amount of money to draw on from his royal coffers, Ludwig I scooped up many highly sought-after pieces. To display his massive collection, Ludwig I commissioned the construction of a number of major museums. One of his first projects was the Glyptothek, which was used to house ancient sculptures. Another, the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiquities), was designed in 1848. The works from that institution formed part of the extensive collection of the Bavarian Royal Family.

Ludwig I’s taste in art also ventured beyond the ancient world. In 1836, he created the Alte Pinakothek, the largest museum in the world at the time of its inauguration. Ahead of his time, Ludwig I also established one of the first contemporary art museums in the world–which was unfortunately destroyed by bombing during WWII.

Ludwig I had a deep appreciation for ancient masterpieces and structures evoking the classical era. Projects inspired by this passion include the Propylaea, a monumental city gate constructed as a copy of the Athenian Acropolis and ultimately dedicated as a memorial for Ludwig I’s son Otto, who ascended to the throne of Greece in 1832. It was financed by Ludwig I’s private resources after his abdication, and serves as a symbol of friendship between Greece and Bavaria. While he was still a young crown prince, Ludwig I conceived the project of Walhalla, a temple erected to honor famous Germans. This hall of fame honors nearly 200 laudable people spanning 2,000 years of German history, including both male and female politicians, sovereigns, scientists, and artists, from Albrecht Dürer to Sophie Scholl. Although it is named after the Norse mythological heaven for warriors, the temple was built in the Greek Revival Style and modeled after the Parthenon. The temple continues to be used today, and 19 busts, including one of Albert Einstein, have been added to the collection since WWII.

Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Germany, as restored today

© Carole Raddato (owner of Following Hadrian)

Ludwig I also aspired to bring a bit of ancient Rome to Bavaria. As such, he commissioned the Pompejanum, mentioned above, which was constructed between 1840-1848. Designed by architect Friedrich von Gärtner, it was loosely modeled on the House of the Diosuri (Casa dei Dioscuri) in Pompeii. The villa was never intended to be used as a residence; rather, it has always served as a museum. Located near Schloss Johannisburg (one of Ludwig I’s residences), the king could admire it from his window and make frequent visits. Completed with a Mediterranean-style garden and filled with reproductions of mosaics, architectural forms, and artifacts, the king could escape to Italy with just a short trip to the Pompejanum.

Visitors came to the Pompejanum because it was, and perhaps still is, the most accurate reconstruction of a Roman villa in the world. The ground floor features an entrance hall, the guest room, the kitchen, the dining room, and atrium, all organized around two courtyards. The interiors were painted in the Pompeiian fresco style, and the floors feature copies or adaptations of ancient works and Roman mosaics. The collection included Roman marble sculptures, bronze statuettes and glasses, and household items, as well as two god’s thrones made of marble.

The Pompejanum destroyed after WWII bombings

Sadly, as often happens during conflict, the damage to the museum’s physical structure led to the loss of its collection. The Pompejanum and the surrounding areas were heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1944 and 1945. Some of the museum’s objects survived bombing only to be looted. But nothing looted from the museum was ever sold by the museum or German government, and thus title to any looted property remained with the Bavarian State. Under U.S. common law principles, valid title to artwork cannot be transferred through looting. There must be a legitimate transaction for title to vest legally in a subsequent purchaser. This means that the Bavarian State continues to maintain a legal claim of ownership over objects that were taken from the Pompejanum.

The Pompejanum was eventually restored during several phases, the first beginning in 1960. The restoration was completed in 1994, and the villa reopened to visitors that year as the museum of the Bavarian Palace Department and the State Antiquities Collections. Today, it is open to visitors from the spring through the fall.

Establishing the provenance of artwork and antiquities is essential, particularly for objects displaced during times of conflict. It is important not to underestimate the role of art experts in determining provenance, as well as the return and restitution of looted objects. Due to their specialized knowledge and access to resources that are not necessarily available to the public, art experts play a crucial role in establishing the provenance of works and alerting owners to potential red flags. It is always important for purchasers of artwork with unclear provenance or gaps in the chain of ownership to consult experts and ensure that title has been properly transferred.

This pre-war-photo shows the Bust, together with another (today in the Antikensammlungen), standing in the Atrium at the entrance of the Tablinum.

To research her new-found treasure, Ms. Young contacted Sotheby’s. The auction house’s consultant researcher in Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, Jörg Deterling, identified the subject of the Marble Bust as Drusus Germanicus and alerted Ms. Young that the work had gone missing from the Pompejanum decades ago. Before being looted, the Marble Bust had been displayed in the Atrium, at the entrance of the Tablinum that led to the Pompejanum. Although the exact path of the Marble Bust from Bavaria to Texas is unknown, it is safe to assume that it was looted either by an American serviceman who brought it back to the U.S. or by someone who eventually sold it to an American, likely during WWII or immediately after the end of the conflict.

According to Sotheby’s, Mr. Deterling has been “responsible for many returns, restitutions, and repatriations over the years, but his name has never appeared anywhere in connection with them.” Here, he once again played an instrumental role in the return of a valuable artwork by informing Ms. Young about the historical significance and provenance of her find.

Drusus Germanicus on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art

After being informed of the Marble Bust’s provenance, Ms. Young worked with Amineddoleh & Associates to voluntarily transfer title to Bayerische Verwaltung der staatlichen Schlösser, Gärten und Seen (the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens and Lakes), a government agency in Bavaria, Germany. As part of the restitution agreement, the Bavarian agency committed to loaning the Marble Bust to the San Antonio Museum of Art where it is expected to remain on view until its scheduled return to Germany in 2023.

Rather than sell the Roman bust on the antiquities market, where she could have made hundreds of thousands of dollars, our client instead chose to act ethically and return the bust to its rightful home. We worked with Ms. Young to communicate with German authorities, negotiate the transfer of title, ensure proper acknowledgement of Ms. Young’s actions, and request the work’s temporary display in Texas where its story and our client’s role could be further relayed. The Marble Bust’s journey is an extremely important story to tell. It reflects our passion for the past and collecting, the value of museums in providing access to heritage and knowledge, the unfortunate displacement and destruction of national and cultural heritage during conflict, and the hope that people and institutions will choose to act ethically and protect our shared heritage.

In fact, earlier this week the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced the return of a looted marble sculpture to Italy. As in the case with Drusus Germanicus, the object was likely stolen during WWII. The MFA had purchased the antiquity from a Swiss dealer in 1961 for $750. Other records of its whereabouts prior to the purchase are lost, but the dealer had represented that the object originated from Rome. Unfortunately, the MFA’s sculpture had suffered significant damage, such as the loss of facial features, including its nose, mouth and lower left cheek. The Boston museum worked with the Italian Ministry of Culture to effectuate the return of the looted antiquity.

At Amineddoleh & Associates LLC, we are proud to represent clients who value cultural heritage and consult us in matters involving provenance, authentication, ownership, and restitution. In doing so, they help ensure that cultural heritage is protected and safeguarded for current and future generations while being shared with as many people as possible. Thank you to The Art Newspaper for sharing details about this story HERE.

Leila A. Amineddoleh was quoted in Le Parisien after speaking with a French journalist about the seizure of 180 items from Michael Steinhardt’s antiquities collection. Leila served as an expert for the seizure of a number of items removed from the Steinhardt collection, including the Bull’s Head that triggered the investigation into the financier’s collection. Details are available HERE.

Like other nations rich in archaeological material, Mexico has suffered a great deal of looting and illegal export of its cultural heritage over the past decades. Despite enacting protective legislation dating back to the late 19th century, cultural heritage objects from Mexico continue to be smuggled out of the country and sold on the open market. These items, many of which hail from pre-Columbian indigenous societies such as the Maya and Aztec, are highly prized by museums and private collectors alike. Stelae (free-standing commemorative monuments erected in front of pyramids or temples and made from limestone), polychrome vessels, jade and gold funerary masks, stone altars, and sculptured figurines are among the many types of objects offered for sale. This is a profitable business worldwide; according to Sotheby’s, its auctions of these items have reached nearly $45 million over the past 15 years. (One of our previous blog posts details the theft of pre-Columbian antiquities worth over $20 million from Mexico’s National Museum of Archaeology on Christmas Day 1985, and how authorities recovered them 3 years later.)

Pre-Colombian Stelea

Photo Credit: National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

In light of these circumstances, Mexico has recently taken several concrete steps to strengthen efforts to track down and recover cultural and historical artifacts. In 2011, the National Institute for Anthropology and History (NIAH) announced the launch of a new unified database for cultural property, which allows for the inscription of cultural goods from anywhere within Mexico. Each item in the database is provided with a unique ID number and accompanying details (such as type, material, dimensions, and provenance), resulting in a publicly accessible and standardized system. This is an invaluable tool that will aid the government in protecting the country’s approximately 2 million movable artifacts.

Mexico has also implemented measures to further protect heritage items already removed from within its borders. In March 2013, the governments of Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Peru contested the sale of pre-Columbian art from the Barbier-Mueller Museum at Sotheby’s Paris. All these countries have similar laws vesting ownership of antiquities in the State; therefore, they alleged that the sale was illegal because the objects were not accompanied by export licenses or sufficient provenance information confirming that the works were removed prior to the passage of the relevant laws. Nonetheless, the sale went ahead as planned. A French diplomat stated that the items did not appear on the Interpol database or ICOM Red List, and as such were not considered looted or stolen. (This statement was made even though pre-Columbian antiquities are underrepresented on both lists.) Ultimately, nearly half of the lots failed to sell, and the total sales proceeds fell far below the pre-sale estimate. Public pressure may have played a role in staving off bidders.

Despite this controversy, auctions of similar items have continued. In September 2019, Mexico and Guatemala jointly denounced the auction of pre-Columbian artifacts at French auction house Drouot. The auction house claimed the sale was “perfectly legitimate” and proceeded to sell 93% of the lots, netting $1.3 million for the sale. In response, the consigner, Alexandre Millon, stated that he was a victim of “opportunistic cultural nationalism.” This stoked further tension among countries of origin and market countries.

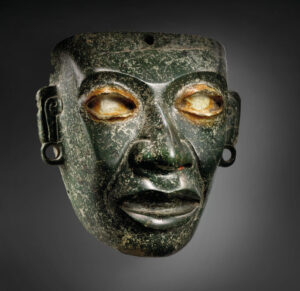

Teotihuacan mask, ca. 450–650

Photo Credit: Christie’s

In February 2021, NIAH lodged a formal legal claim against Christie’s over the sale of 33 pre-Columbian objects, including a stone sculpture of the goddess of fertility Cihuatéotl estimated at $722,000-$1.08 million and a Teotihuacán green stone mask of Quetzalcóatl estimated at $420,000-$662,000. Notably, the mask previously belonged to French dealer Pierre Matisse, son of artist Henri Matisse. While Christie’s maintained that it was confident in the legitimate provenance of the items, historian and archaeologist Daniel Salinas Córdova indicated that the circumstances under which the items had left their places of origin was still unclear. He reiterated that auctioning pre-Columbian antiquities is dangerous because it “promote[s] the commercialization and privatization of cultural heritage, prevent[s] the study, enjoyment, and dissemination of the artifacts, and promote[s] archaeological looting.” Although the sale proceeded and the legal claim has not yet been resolved, Mexico continues to enforce its patrimonial rights.

In September 2021, ambassadors from 8 Latin American Countries (Mexico, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, and Peru) banded together to stop an auction of pre-Columbian artifacts in Germany. Mexican Secretary of Culture Alejandra Faustro sent a letter to the Munich-based dealer, Gerhard Hirsch Nachfolger, citing Mexico’s 1934 patrimony law and reiterating the government’s commitment to recovering its cultural heritage. Mexico’s ambassador to Germany, Francisco Quiroga, even visited the auction house in person in an attempt to block the sale. A complaint was also filed with the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico. The auction took place, but of the 67 pieces identified as being Mexican, only 36 sold. Notably, one of the highlights – an Olmec mask with an estimate of €100,000 – did not achieve the reserve price.

That same month, Mexico announced the creation of a new team composed of National Guard personnel tasked with the recovery of stolen archaeological pieces and historical documents. The nation’s president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, credited Italy with the idea. He stated, “Italy has a special body to recover stolen archaeological pieces. We are going to follow that example, I have given the instruction for the National Guard to constitute a special team for the purpose,” Lopez Obrador said.

As recently as November 2021, the Mexican government issued a letter questioning the legality of two auctions in Paris (at Artcurial and Christie’s) selling pre-Columbian objects. Embassy officials and the Mexican Secretary of Culture asked for the sales to be halted on the grounds that they “stri[p] these invaluable objects of their cultural, historical and symbolic essence, turning them into commodities or curiosities by separating them from the anthropological environment from which they come.” Only a few months earlier (in July), the governments of Mexico and France had signed a Declaration of Intent on the Strengthening of Cooperation against Illicit Trafficking in Cultural Property, which was meant to signal a recommitment towards the restitution and protection of each nation’s cultural heritage. Although Mexican officials appealed to UNESCO, bidding opened as scheduled on Artcurial’s online platform (with lots priced at $231-$11,600) and Christie’s earned over $3.5 million in its own sale. The day before the Christie’s sale, the embassies of Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru in France issued a joint statement decrying the “commercialization of cultural property” and “the devastation of the history and identity of the peoples that the illicit trade of cultural property entails.”

Nonetheless, Mexico’s persistence has borne fruit. In September 2021, it was able to halt the sale of 17 artifacts at a Rome-based auction house. The Carabinieri TPC seized the objects after an inspection revealed that they had been illegally exported, and returned them to Mexico in October. The successful recovery of these objects demonstrates the importance of international cooperation. Many governments’ resources are stretched thin policing their own borders for cultural heritage smuggling and theft, and therefore greatly benefit from assistance by foreign law enforcement. It is also an example of how successful cultural diplomacy can be in the recovery of such objects.

The letter signed by Hernán Cortés recovered by the Mexican authorities.

Photo Credit: The National Archives

In addition to law enforcement and government agencies, laypeople have a crucial part to play in the recovery of looted or illegally exported artifacts. For instance, a group of academics in Mexico and Spain helped thwart the sale of a 500-year-old letter linked to conquistador Hernán Cortés. The letter, dating back to 1521, had been offered for sale by Swann Galleries in New York in September 2021. It was expected to fetch $20,000-$30,000. By searching online catalogues of global auction houses and a personal trove of photographs depicting Spanish colonial documents, the group traced the letter’s provenance to the National Archive of Mexico (NAM), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. An image of the letter had been taken by a Mormon genealogy project, which provided supporting evidence. Furthermore, the group unearthed 9 additional documents linked to Cortés that had been sold at auction – including at Bonhams and Christie’s – between 2017 and 2020. One of these had been sold previously at Swann Galleries for $32,500 and later displayed at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York as part of an exhibition. It was confirmed that all the documents had been stolen from the NAM – they were surgically excised from books – and illegally exported. In response, Swann Galleries cancelled the planned auction. The purchaser of the aforementioned letter returned it in good faith to the auction house. Mexico’s Foreign Ministry enlisted the help of the US Department of Justice to repatriate the 10 manuscripts, in cooperation with the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office and Homeland Security Investigations. The manuscripts were formally handed over in September 2021.