In addition to offering compelling information to historians and art lovers, provenance often plays a central role in ownership disputes. Essentially, you cannot demand the return of an object, if it wasn’t yours to begin with. Without proof of ownership, a party lacks legal standing to successfully make a claim for restitution. (“Standing” is a requirement of Article III of Constitution. It is the term for the ability of a party to demonstrate a sufficient connection to and harm from the law or action challenged to support that party’s participation in the case. In simple terms, courts use “standing” to ask, “Does this party have a ‘dog in this fight?’”) For this reason, determining provenance is vital in lawsuits involving stolen property because only parties with an ownership interest can demand restitution.

Oftentimes provenance is central to matters related to Nazi-looted art. But proving ownership can be extremely difficult for individuals victimized by the Nazis because of the events that occurred during WWII. The displacement of art during the war was vast; it is estimated that 20% of art and valuables in Europe were looted by the Nazis (this includes items such as musical instruments, jewelry, furniture, porcelain, books, and other personal property). Sadly, most owners lack documentation to support their restitution demands. As people fled their homes and countries, they left behind not only their property, but paperwork associated with those items. Without that documentation, it is an incredible burden to make a claim for restitution because it is nearly impossible to prove ownership. But for the small minority of owners able to successfully demand return of their property, crucial evidence is sometime found in the most unexpected of places.

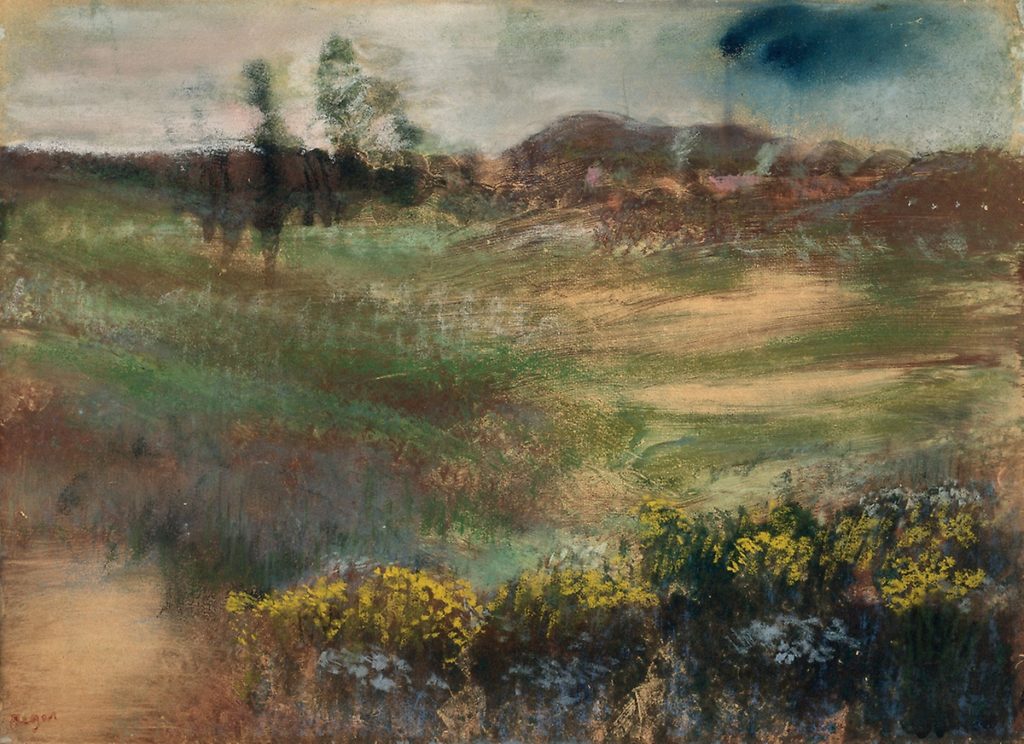

That was exactly what led the Goodman (Gutmann) Family to pursue a restitution case against Daniel Searle, a collector who had purchased a stolen Degas landscape. The Gutmanns (a wealthy banking family) had an enviable art collection that the Nazis coveted. Landscape with Smokestacks was placed in storage by the Gutmann Family in 1939 in order to save it from Nazi seizure. However, it was eventually taken by the Nazis after the work’s custodians perished in concentration camps. The Degas painting then resurfaced in Switzerland after the war, and then was acquired by a New York collector in 1951. It was eventually sold to Daniel Searle in 1987, with the assistance of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Interestingly, the Gutmann heirs began a quest to recover an impressive art collection after one of the heirs discovered his true identity. Simon Goodman, whose father had moved to England and changed his name from Gutmann to Goodman, had grown up unaware that he was Jewish or that his family owned an incredible art collection. He had discovered this information after receiving a collection of boxes after his father’s death that contained information about his family’s looted collection and ownership information about some of the pieces.

The Degas painting was on the inventory of missing family treasures. During their research, the Gutmann heirs came across a photograph of the work. “Monuments Woman” Rose Valland heroically recorded information about plundered art, and after the war, presented one of the surviving Gutmann family members with images of their looted property. Although only a black-and-white photo, it was used to establish the provenance, verify legal ownership claims, and resolve the legal dispute. The lawsuit lasted over two years, and ended with a settlement. Searle donated a fifty percent ownership interest in the work to the Art Institute of Chicago, and ceded a fifty percent interest to the Gutmann heirs. As part of the agreement, the museum purchased the Gutmann’s interest based on the market value. It was the first dispute over Nazi-looted art settled in the U.S.(For more information about the Gutmann Family’s provenance research and legal battles, Simon Goodman’s The Orpheus Clock is a gripping book about his family’s struggles.)

Determining provenance can be very challenging. Over time, information about a works’ ownership is lost. Sales documents and receipts are lost, first-hand knowledge about transactions slowly disappears as individuals involved in a sale pass away and memories fade. It is especially challenging to piece together a provenance when parties conceal this vital information. Thieves (whether they are individuals or groups) attempt to erase the truth about works, or create a false provenance, so that they can lay claim to the property. This is exactly what the Nazi Party did as it stole art and valuables across Europe.

In 1943, the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAA) was established under the Civil Affairs and Military Government sections of the Allied armies. Its members, better known as the Monuments Men, worked to protect artworks, archives, and monuments in Europe. 345 men and women served in this group, including well-known art professionals, including curators and historians from the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harvard and the New York City Ballet. With an overwhelming task to protect sites and return works to rightful owners, the Monuments Men faced an incredible hurdle. Making things even harder were limited resources and a short timeframe in which to conclude their work. Although many works remain missing to this day, the Monuments Men were able to return more than five million looted cultural items.

The first museum in the United States to hire a full-time provenance researcher was the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. In 2003, they hired Victoria Reed to serve as Curator for Provenance. She has been instrumental in conducting research that has led to the return of a number of stolen arts or payment of financial settlements to rightful owners, such as with Eglon van der Neer’s Protrait of a Man and Woman in an Interior. (Following the MFA’s lead, a number of other institutions have hired provenance researchers to examine items in their collections.) While the MFA Boston is closed, Dr. Reed is posting daily tweets about artworks from the museum’s collection that feature interesting provenance information.

Our founder has served as counsel on a number of stolen art matters. One of the cases in which she served as lead litigation counsel involved a civil forfeiture. Civil forfeiture occurs when government agents seize property suspected of being involved in criminal activity. The property owner doesn’t have to be charged with a crime, so the case is actually against the property itself which is why some forfeiture cases have unusual names. Case in point: United States of America v. The Painting Known and Described as ‘Madonna and Child’ attributed to the Florentine Painter Active In The Ambit of Cimabue, Circa 1285–1290, held by Sotheby’s in New York.

The three-decade long disappearance of the thirteenth century painting is a tale about the development of provenance in a legal battle. The story begins in 1977 with the purchase of the panel from a religious mission in London. Co-owners of the painting sold partial interests in the work to other art collectors so that each of the parties owned a percentage of the work. After its purchase, the parties placed the work in a jointly-rented safe deposit in Switzerland, and tried to market the work to sell it.

Unbeknownst to the other parties, one of the co-owners moved the painting to his own safe deposit box in the mid-1980s. In early 1990, he was brought to court. There was an order from an English judge restraining him from selling the painting. However, he used aliases to market the painting. Eventually he hid the painting and he fled to France, and a series of legal conflicts and international police investigations began. The situation quieted down and the co-owner died in Florida in 2006. He left his interest in the painting to his wife who eventually consigned the work in Sotheby’s in 2013.

Due diligence at Sotheby’s revealed that the painting was stolen after the Art Recovery Group discovered that the work appeared in its database of stolen art. The January 2014 sale was stopped. In June of that year, the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York filed a complaint against the stolen painting, and Sotheby’s voluntarily forfeited the work. At that point, anyone with an ownership interest was invited to file a claim with supporting documentation. Although there was a gap of over twenty years during which time the painting was hidden, there was substantial documentation supporting our clients’ claims. We developed the evidentiary record in the form of an extensive provenance by supplying the original purchase and sales documents (from the 1970s), bank records from the safe deposit, signed and notarized affidavits, police and INTERPOL reports, the power of attorney allowing one of the owners to sell he work on behalf of the consortium of owners, postmarked letters from the time of the painting’s disappearance, one of the owner’s wills that specifically named the piece, a 1990 article in the Antiquities Trade Gazette, and court decisions against the thief.

With such strong proof of ownership, the case was resolved in the spring of 2015; title was returned to the legitimate owners, and the work was auctioned at Christie’s, with proceeds going to the rightful parties. The co-owner’s widow thought she would be able to sell the work painting because the other co-owners had lost track of the piece over the long lapse of time. However, ownership is part of the permanent provenance that accompanies a work.

Our civil forfeiture case cleared any clouds on the title and the current owner (the individual who purchased the painting at auction) has perfect title because a US court made a definitive ownership determination (as Christie’s noted in its catalog.) The only unanswered question now is attribution (we will address attribution in future posts). The lack of provenance prior to the 1977 purchase makes it particularly challenging to identify the attribution. As of now, the author is identified as “a close follower of Duccio.”