What is it about children and their love of toy dolls? The iconic American Girl Dolls continue to take center stage in American childhoods, alongside another classic doll: the one and only Barbie doll. For some Americans, Barbie dolls feature in every memory of their childhood.

The connection to dolls, formed in childhood, may linger into teenage and adulthood years. In fact, those who grew up toting Barbies everywhere are likely the adults eagerly anticipating this summer’s blockbuster film of the same name. It’s a safe bet that the new promo for Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie, starring Margot Robbie as Barbie, has danced across their phone screens. The short teaser clip, released last month, has already banked over eight million views on YouTube, through the Warner Brothers’ official YouTube handle.

In Japan, young children also have a special relationship with dolls. However, for Japanese girls, the dolls are not Barbie dolls. Instead, they are ones displayed each year during a holiday known as Hinamatsuri.

Traditional Japanese Holiday: Hinamatsuri

The Hinamatsuri, or what is known as the “Girls’ Festival,” is a special day for families with daughters. On this day, March 3rd, Japanese families who have daughters celebrate them by presenting them with beautiful dolls, called hina-ningyo, in a dollhouse-like display. The beautiful arrangement is then adorned with fresh peach blossoms. These pink blooms are the fauna associated with the holiday. Their purpose is to ward off evil spirits, as the families wish their daughters success and happiness in their lives.

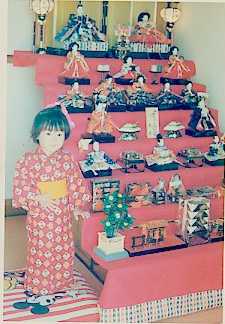

Natsuko Suwa as a child, standing in front of her dolls on Hinamatsuri. Image courtesy of Natsuko Suwa via Japanese Culture Exchange.

Hinamatsuri celebrations began in Japan during the ancient Heian Period (794-1192) with paper and straw dolls. This changed during the Edo Period (1603-1868). At that time, the dolls began to be made of a combination of ceramic and fabric. The dolls themselves became more central to the celebration during this time, possibly because of the heightened attention to the craftsmanship of the dolls themselves.

Originally, only two dolls were used in the festival: a bride doll (representing the empress) and a groom doll (representing the emperor). These two dolls are still important to modern Hinamatsuri displays in Japan. Parents typically purchase these two figures for their daughters after she is born. Because the dolls can be very expensive, another option for some households is to pass dolls down through female family members.

Displays of hina-ningyo dolls can be intricate and include more than just the two original dolls. After the Edo period, the most prestigious sets consist of seven platformed layers. Today, it is more common for households to display one-to-three layered sets of Hinamatsuri dolls. In these expanded displays, the additional layers provide room for a wide variety of royal court attendees, including three court servants (San-nin Kanjo) and five boy musicians (Go-nin Bayashi). Other layers are added, to ensure that the display contains seven layers in total, for good luck. Miniatures typically take the spotlight on these lower layers. Some may also have small versions of traditional Japanese tea sets or Japanese musical instruments.

Dining with Dolls

The traditional foods of Hinamatsuri are as alluring and aesthetically delicate as the dolls themselves. In preparing these foods, and serving them to share, Japanese families engage in the social practice of Washoku. Washoku is an intangible cultural heritage tradition, recognized in 2013 by UNESCO on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (8. COM).

UNESCO defines Washoku as “a social practice based on a set of skills, knowledge, practice and traditions related to the production, processing, preparation and consumption of food.” Washoku is typically associated with Japanese New Year celebrations, the three-day holiday known as Oshogatsu. However, the practice itself extends beyond the Oshougatsu celebration, and is seen in traditional Japanese meals all throughout the year. In fact, the Kanji characters used to write the word “Washoku” are comprised of two characters, the literal translation of which is “Food of Japan.” As a result, visitors to Japan will experience Washoku during any traditional Japanese meal, whether it occurs on a holiday, such as Hinamatsuri, or not.

The practice of Washoku involves making beautiful dishes using symbolic ingredients to communicate specific wishes and blessings during the meal. The skills used to make each symbolic dish, including the proper methods, seasoning, and artistic decorations, are passed down within Japanese households through families. In this way, the cultural preservation of these techniques is accomplished by informal training methods, though formal cooking techniques for these dishes are also taught at culinary schools in Japan. This practice is done in a gorgeous fashion during Hinamatsuri.

What are the foods eaten at Hinamatsuri, preserved through Washoku? The beautiful cuisine traditionally served during Hinamatsuri communicates meaning that matches this special occasion. Hishimochi, a tri-colored rice cake, takes center stage at Hinamatsuri celebrations in Japan. Traditionally made of three, pastel-colored layers of cake, the diamond-shaped cake is typically displayed alongside the dolls. The pink, white, and green layers of rice cake symbolize Sakura blossoms, snow, and new growth. Taken together, the entire cake represents fertility, and is meant to promote good fortune for the daughter who takes a delicious bite.

The same color palette appears in another delicate traditional food on this day: hina arare, or colored rice crackers. Hina arare are sugar-coated puffed rice crackers dyed in pink, green, yellow, and white.

An artful display of Chirashi-zushi, or scattered sushi. Image via Schwin Pikulsawad at Dreamstime.com.

Chirashi-zushi, or scattered sushi, makes up the day’s entrée. This light assorted dish is composed of sweetened sushi rice and ingredients that are consistent with the colors of Hinamatsuri. These ingredients differ; an example of toppers for the sweetened sushi rice that are commonly used are pink shrimp for longevity, beans for steady health, and lotus root for the ability to see ahead.

One dish that does not include the Hinamatsuri colors, but that still holds meaning, is hamaguri no osuimono, a clear soup made of clams. Clams are in season in the beginning of March in Japan. The shells themselves symbolize a happy union in marriage, as the unique joined shells fit together in harmony.

To drink, the girls drink a small portion of toukashu, a sweet, rice wine with peach blossoms floating in it. Peach blossoms have always been known to ward off evil spirits in Japan, so this is the perfect beverage for this special holiday.

Artistry of Hina-Ningyo

The artists who create hina-ningyo dolls have artisan workshops in Japan, and they rely on techniques that have been passed down through artists for centuries. Typically, employees at these workshops will construct the doll pieces separately. The next step is to deliver all the individual doll parts to the shop’s master artist, who will then spend as many as five days constructing just one single hina-ningyo doll.

Two hina-ningyo dolls on display. Image courtesy of Natsuko Suwa via Japanese Culture Exchange.

The time and energy spent in the workshops that produce authentic hina-ningyo dolls in Japan is a testament to the importance of this holiday in Japan, as well as to the sacredness of these dolls in the lives of Japanese households. Originally, it was believed that each hina-ningyo doll had the ability to absorb evil spirits. This belief stemmed from ancient tradition, in which the third day of the third month was deemed a day of purification. To purify the household and promote a healthy future, the custom was to transfer evil spirits into dolls. The dolls were then sent on boats downstream to release the bad spirits rivers and oceans. This custom was called hina nagashi.

Today, custom has shifted, and dolls are instead displayed on the ornamental, tiered structures discussed above. This way, the beautiful craftsmanship of the dolls is preserved, while still respecting the original, sacred purpose of hina-ningyo dolls.

Are Hina-Ningyo Dolls Copyrightable?

Legal eagles among us may see such breathtaking artistry and wonder: are dolls of this type copyrightable? With this level of craftsmanship and creativity on the line, what level of intellectual property protection may be available to artists?

U.S. caselaw is instructive on this point. Although many aspects of a doll may not be copyrightable under the Copyright Act, some elements of each hina-ningyo doll may be copyrightable by the artist, if they are sufficiently original. This may result in only minor copyright protection for a hina-ningyo doll master, but it could provide some protection, if the facial expression or certain design elements of the doll’s clothing are sufficiently distinctive.

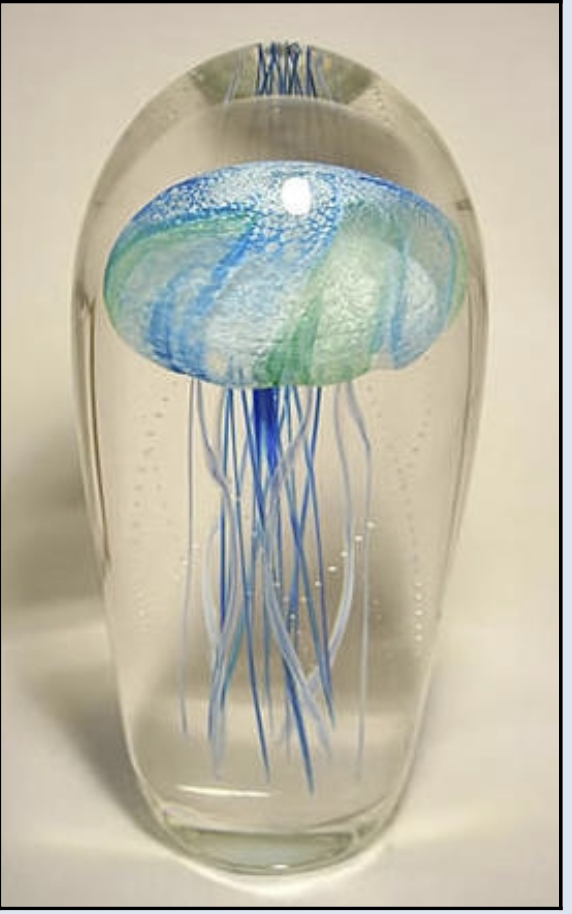

The closest case on point is likely Satava v. Lowry, a 9th Circuit decision in which two artists created similar sculptures of jellyfish enclosed in glass. Richard Satava, a California-based glass artist, became famous for his iconic glass-in-glass sculptures of jellyfish. His sculptures – which are still being produced – sell for thousands of dollars. At the time of the lawsuit, he was regularly making upwards of 300 sculptures per year. Several of his works had been registered with the Register of Copyrights, and (perhaps even more telling) many consumers could identify his works on-sight, due to their signature design.

Jellyfish sculpture created by Richard Satava. Image obtained via satava.com.

Defendant Christopher Lowry, a Hawaii-based glass artist, separately began making glass-in-glass sculptures of jellyfish. Lowry’s designs were so similar to Satava’s that consumers confused the works by the two artists. Satava sued Lowry, demanding an injunction, which the district court granted. Lowry then appealed, arguing that Satava did not have a protected copyright over the jellyfish sculptures.

The court reviewed different elements of the sculptures to determine whether or not the defendant had infringed on the Satava’s designs. In reviewing the pieces, the court came away with a list of elements that could be copyrightable, and those that could not.

According to the 9th Circuit, the elements deserving copyright protection were unique colors, shapes, and lines that were unlike a jellyfish’s natural depiction. This stems from the reasoning that the artists’ decisions in creating more fanciful renditions or interpretations of jellyfish speak to the originality requirement at the heart of the Copyright Act. In contrast, the elements of the sculpture that were not copyrightable were the ones that mirrored a jellyfish in its natural habitat. This included features such as jellyfish bells and tentacles, and the jellyfish’s suspension in glass, imitating its movement in water.

A jellyfish sculpture by artist Christopher Lowry, currently for sale. Image obtained via artglassbygary.com.

After examining each sculpture, the outcome of this case was a bit surprising. The court found for Lowry, holding that he could not be prevented from creating jellyfish sculptures similar to Satava’s. Even though the artists’ sculptures were similar, Satava failed to supply sufficient proof that Lowry had copied the protectable design elements of Satava’s work.

What would have changed the outcome of that case? This was a close case, and the outcome hinged on the 9th Circuit’s application of the originality test. To be fair to Lowry, Satava’s sculptures are – in essence – realistic-looking jellyfish in a kind of upside-down dome. It is entirely possible that Lowry could have (and likely did) come to create his own version of jellyfish in an upside-down elongated jar, completely by his own faculties. Moreover, Lowry lived in Hawaii, literally by fish and aquatic themes, ripe for applying to his glasswork. Is it any surprise that the jellyfish-in-a-jar idea came to him, as well?

On the other hand, Satava had established a reputation for himself for creating iconic jellyfish sculptures. The sculptures were popular with and recognizable to art lovers across the country. Additionally, consumers actually confused Lowry’s pieces with Satava’s highly sought-after work. In the end, the court held that the protectable elements of Satava’s work – such as unique lines, shapes, and color combinations – had not been infringed upon.

Perhaps if Lowry had made outright replicas of Satava’s work, the 9th Circuit would have upheld the district court’s injunction against Lowry. This is what happened in Mattel, Inc. v. Goldberger Doll Mfg. Co., where the Second Circuit Court of Appeals analyzed a copyright infringement claim by Mattel against another doll manufacturer.

In Mattel, the defendant, Radio City Entertainment, created a doll to celebrate the famed Rockettes for the 2000 millennium festivities. Mattel brought suit against Radio City, arguing that their Rockettes doll infringed on their registered copyrights for two separate Barbie dolls: “Neptune’s Daughter Barbie” (registered in 1992) and “CEO Barbie” (registered in 1999). Mattel argued that Radio City had essentially combined the features of those two registered dolls to produce the Rockette doll, in a Frankenstein-esque fashion. Radio City moved for summary judgment, which the district court granted. For the purposes of summary judgment, the district court held that Radio City had copied the Mattel Barbies’ “eyes, nose, and mouth,” but that Mattel had no copyright in those “common elements” of a “youthful female doll.” The court went on to identify those unprotectable elements as “full faces; pert, upturned noses; bow lips; large, widely spaced eyes; and slim figures.”

Here is where this case gets tricky: because the district court had, for the purposes of summary judgment, already held that the Rockette doll had copied the Barbie dolls’ eyes, nose, and mouth, but that Mattel had no copyright in those elements, the remaining similarity determination was made without including the face. As a result, the district court found for Radio City.

Mattel appealed to the 2nd Circuit. On appeal, the 2nd Circuit held that the district court’s conclusion that the eyes, nose, and mouth of the Barbies were not protected by copyright was erroneous. The 2nd Circuit applied the originality test with a lower bar than the 9th Circuit in Satava. Here, the 2nd Circuit held that the Barbies’ faces, despite containing common elements, had satisfied the “minimal degree of creativity or originality” necessary to obtain copyright protection. The court went on to explain that such protection in facial features – particularly for a doll of a certain type – is limited. Some features, common amongst the Disney princess set (wide eyes, upturned nose, bow lips), compose an idea of a face that belongs to the public domain. However, on these facts, the 2nd Circuit held that Mattel’s copyright extended to the particular expression of the Barbie faces.

As a result, the 2nd Circuit remanded the case back for further proceedings. In response, the parties entered into a settlement agreement, and litigation ceased. These two cases are similar, but yielded dramatically opposite outcomes. What distinguishes these two cases from each other?

The answer may simply boil down to the discretion of the court, and the originality test the court applies based on the facts at issue. The outcomes in these two cases illuminate the difficulty of applying the U.S. Copyright Act and copyright case law, particularly when modern culture influences a judges’ definition of what “counts” as artistry, creativity, and originality. It raises the question of whether or not precedent is the most uniform way to understand the Copyright Act. Perhaps it is time copyright protections in the U.S. benefited from some clearer legislation.

Moreover, and particularly applicable in the Mattel case, the court seemed to base its originality determination on what is culturally considered a “doll face” and a “doll body” using a (now dated) set of criteria. In 2023, such a list of elements read as discomfortingly patriarchal. It calls to question whether the same court would apply the same test differently today, based on the modern introduction of a wider selection of popular Barbie dolls. Does the social and cultural movement toward embracing multiple body types, skin tones, and diverse faces change the way a court approaches the originality test for dolls?

Rights of Artists

For artists creating hina-ningyo dolls, lingering questions mean that some aspects of the dolls may be copyrightable, while others are not. This does not give much copyright protection to the artist. But artists may still be protected from another artist flat-out replicating their work under the Copyright Act. Doll artists around the world who seek to protect their work might consider focusing on their dolls’ exact proportions, composition of facial features, and recognizable design elements when they consider registration. Even so, registering specific doll elements may not fully protect the artists’ work from infringement, because, under the current legal landscape, the exact test for originality turns on the interpretation of the sitting court.

Suwa’s display of dolls on Hinamatsuri. Image courtesy of Natsuko Suwa via Japanese Culture Exchange.

Role of an Art and Cultural Heritage Lawyer

Staying abreast of important holidays in other cultures is an essential component of any art and cultural heritage law attorney’s work, because knowledge of local celebrations fosters understanding and connection with new groups of people. To study Hinamatsuri, for example, is to become a student of the deep love present within Japanese families. A day set aside to celebrate daughters? Filled with delicate pastries, pastel colors, and prized doll collections? Count this writer in.

Cultural information for this post was aided by Natsuko Suwa. Suwa is an instructor at Japanese Culture Exchange, a language school located in Raleigh, NC that offers virtual and in-person language lessons.