The following article was contributed to Amineddoleh & Associates LLC by Emily A. Thompson, AAA. Ms. Thompson is an art advisor and qualified appraiser certified by the Appraiser’s Association of America (AAA) in post war, contemporary and emerging art. She serves on the membership committee of the Estate Planner’s Council of New York (EPCNYC) and maintains an adjunct faculty position with Sotheby’s Institute of Art.

As art fairs cautiously return and the auction season gears up, increased sales and acquisitions warrant a re-examining of due diligence in art transactions, both online and in real time. According to best practices suggested by non-profit initiative RAM (the Responsible Art Market initiative), “due diligence” is commonly defined as “action that is considered reasonable for people to be expected to take to keep themselves or others and their property safe”.[1] While there are companies proclaiming to eliminate art market risks via software programs, collectors should ask probing questions. Working with a seasoned advisor with art expertise can be invaluable because that person can spot inconsistencies in paperwork, investigate the validity and reputation of a source, and flag concerns for a collector’s attorney or tax advisor.

As art fairs cautiously return and the auction season gears up, increased sales and acquisitions warrant a re-examining of due diligence in art transactions, both online and in real time. According to best practices suggested by non-profit initiative RAM (the Responsible Art Market initiative), “due diligence” is commonly defined as “action that is considered reasonable for people to be expected to take to keep themselves or others and their property safe”.[1] While there are companies proclaiming to eliminate art market risks via software programs, collectors should ask probing questions. Working with a seasoned advisor with art expertise can be invaluable because that person can spot inconsistencies in paperwork, investigate the validity and reputation of a source, and flag concerns for a collector’s attorney or tax advisor.

An independent advisor may represent a collector in the sale of a work or group of works, or in acquiring art for a new or nascent collection. His or her role should be to aid clients not only by homing in on aesthetic goals, educating them about art and saving them money, but also by minimizing risk and keeping clients safe. Of primary importance, the advisor should abide by a code of ethics whereby they serve the needs of the client and are compensated by one party only. Art advisors may be compensated on a retainer basis, being paid an annual sum by the client based on the anticipated purchases during the year, or on a percentage basis per transaction, or a combination of both. If operating on a percentage basis, a sliding scale is often instituted, with a lower percentage charged by the advisor when the final sales price is above a certain threshold. Whatever the agreed upon arrangement, the payment structure and term of engagement should be outlined in a written contract or agreement letter prior to any acquisition or sale, with clarity on fee structure established at the outset, to ensure transparency and obligations.

The Object and Ownership interest

When evaluating object(s) in question, steps are required to verify the validity of what is being bought or sold and who has the legal authority to do so. On the buying side, it is not uncommon in the art world for an advisor to be offered the same picture by multiple parties – an image and some cataloguing information is no guarantee that the party offering the artwork has the authority to act on behalf of the legal owner. An experienced art advisor will work to confirm the ownership interest of the seller by determining how and when the artwork acquired by the seller. If a work is being sourced privately from an auction house or broker, is there a consignment agreement with the legal owner in place? Where is the work located? Is the artwork free of any liens against it which would affect the passing of clear and legal title? If the ownership structure is overly complex or opaque, or answers to ownership questions cannot be answered satisfactorily, an attorney may need to be consulted.

Due diligence should also be conducted on the object itself. Basic cataloguing describing the artist, medium, size and date of the piece(s) should be provided. The physical condition of an object should be clearly stated and checked, with a physical inspection conducted by the advisor or a contracted, third party, such as a conservator. Is the condition as represented and is it appropriate for the artist or object in question? Have there been extensive restorations or repairs? When reviewing item cataloguing, are there significant gaps in provenance, missing documentation, or lack of dated inventories? Databases such as the Art Loss Register and Interpol’s Stolen Works of Art can be searched to confirm that a work has not been previously lost or stolen. What are the appropriate authentication requirements set forth by market standards? For example, does the work require a certificate of authentication, a letter or ID number assigned from the artist or artists’ foundation or heirs for it to be sold? Is there a catalogue raisonne or established monograph to be consulted? Price databases such as Artnet can be searched for comparable sales as well as previous offerings of the subject work, which may have been omitted from a provided provenance (purposefully or not) and auction house catalogues, printed or now digitally online, can provide valuable information as to relevant literature and the correct expertise for confirming authenticity.

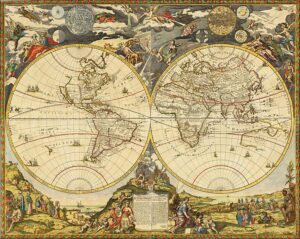

Depending on the collecting category, country of origin or materials may pose serious issues regarding the looting and illicit trafficking of cultural property. An artwork or object originating from known “source nations,” such as Greece or Italy, along with areas of increasing concern, such as Iraq and Syria, may be subject to trade restrictions. Items that were known to be in Europe between 1933 and 1948, in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union during the Communist era (between 1949 and 1990) or in Cuba during the revolutionary period (between 1953 and 1959), to name only a few, should be screened for potential title disputes. Also, some artworks incorporate restricted materials or material from endangered species, such as ivory or snakeskin, which may prohibit their legal trade.

Depending on the collecting category, country of origin or materials may pose serious issues regarding the looting and illicit trafficking of cultural property. An artwork or object originating from known “source nations,” such as Greece or Italy, along with areas of increasing concern, such as Iraq and Syria, may be subject to trade restrictions. Items that were known to be in Europe between 1933 and 1948, in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union during the Communist era (between 1949 and 1990) or in Cuba during the revolutionary period (between 1953 and 1959), to name only a few, should be screened for potential title disputes. Also, some artworks incorporate restricted materials or material from endangered species, such as ivory or snakeskin, which may prohibit their legal trade.

If the art professional offering the piece cannot satisfactorily establish the country of origin of the object and the circumstances under which it left, an attorney specializing in these areas may be needed to consult on the purchase.

Traditionally, the art market is one that has favored secrecy, but recent scrutiny by law enforcement agencies on the use of antiquities and high value art to launder money or evade sanctions has resulted in major implications for dealers, collectors, and anyone else engaged in the art trade. The 2020 enactment of the 5th European AML Directive in the EU and UK and the Anti Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AML Act) in the US have meant new compliance obligations across the industry aimed at increasing transparency in transactions and reducing risk for all parties involved. Collectors should expect to be asked to provide documentation verifying their identity, if buying or selling a work of art, such as a passport, driver’s license, or national ID card, as well as recent proof of residence, such as a current utility bill or bank statement.

Considerations at the transaction level include questioning whether a sale price is artificially low – or high. Are the payment terms suspect in any way (e.g., requests of cash-only transaction or sale proceeds paid to someone other than the seller)? While a contract – from the advisor or with a third-party vendor – will often include language pertaining to confidentiality and privacy, it should be an essential part of an advisor’s business practice to keep his or her own records and to ensure the client is aware of the information necessary to comply with increased regulations. It is also possible to have each side in a transaction reveal its identity to the other’s legal advisors, who can vet the other party and conduct the appropriate reviews.

Post Transaction Duties

Finally, an art advisor’s role should not end with the purchase or sale. On the contrary, additional responsibilities often include reviewing post-sale invoices for errors or omissions, supervising shipping, installation, and cataloguing to ensure that the work is adequately documented for their collection records. An advisor should ensure that the client’s insurance broker is alerted to a new acquisition so that the piece can be added to their scheduled policy and that, once professionally installed, risk factors in the space (high traffic areas, exposure from direct sunlight) are identified and minimized as much as possible.

Art advisors should not be in the business of giving tax advice, the particulars of which can be very complicated and case specific. However, advisors should be aware of possible tax implications for their clients at given points during and post transaction. In the US, sales tax differs by state, so a purchase made away from home could necessitate different filing protocols. Use Tax – when a purchase is made out-of-state and directly shipped to another – also varies by location and must be paid on the purchase in the receiving state.

When selling a work or works from a collection, estate or capital gains tax, the amount owed on the profit of an appreciated asset, may apply. If sold less than one year after its original purchase, income tax, which can be as high as 37%, may be applicable. Depending on the ultimate sale or purchase price, the tax implications for a client can be significant, so it is always good practice for an art advisor to direct their client to their CPA to ensure that there are no unanticipated surprises down the road.

The nature of the art market means ever changing sources, players, and directives. Professional advisors must work to keep pace with regulations and maintain a lawful, unbiased practice in all their dealings, performing the due diligence necessary to serve their clients in the most transparent and ethical manner possible.