In honor of Valentine’s Day, the latest blog post in our Provenance Series centers on the stories of famous lovers and the art inspired by them.

Most people are familiar with playwright William Shakespeare’s famed star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet. This pair from Verona has been immortalized in music, films, subsequent works of literature, and countless works of art. However, there are other ill-fated romantic couples that deserve to share the artistic spotlight.

Dante and Betrice by Henry Holiday

Dante Alighieri, widely credited as the father of modern Italian language, wrote his magnum opus in the 13th century after falling in love with a woman known as Beatrice. Dante admired her from a distance, having only met with Beatrice twice, the first time when they were both nine years old. These interactions moved him so profoundly that Beatrice is widely credited as Dante’s muse even though she was married to another man. Beatrice first appears in Dante’s autobiographical text La Vita Nuova, where she is portrayed as a courtly lady. Beatrice died in 1290. Dante then composed a three-volume narrative poem describing the author’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, where he is eventually reunited with his lady love. This work, The Divine Comedy, is considered one of the great masterpieces of world literature and it was deeply inspired by Dante’s feelings for Beatrice. Indeed, Beatrice serves as the epitome of grace and beauty. She guides the pilgrim Dante into heaven, where his worldly love is transformed into divine love.

Paolo and Francesca da Rimini by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

While Dante and Beatrice meet a happy end in the spiritual realm, other couples in The Divine Comedy are not so fortunate. Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini were real-life contemporaries of Dante who make an appearance in Canto V of the Inferno. Francesca was the wife of Paolo’s brother, who killed them both in a rage after he discovered their secret union. As adulterous lovers, the pair is bonded together for eternity in a fiery whirlwind, symbolizing their uncontrollable lust. But it seems that Dante empathized with Paolo and Francesca’s plight; he wrote that they fell in love while reading medieval romances, particularly those depicting Lancelot and Guinevere (another doomed duo). Upon hearing this, Dante is overcome with pity and weeps for their fate. Despite only occupying 69 lines in Dante’s epic poem, this depiction influenced subsequent generations of artists, particularly the Romantics in the 19th century.

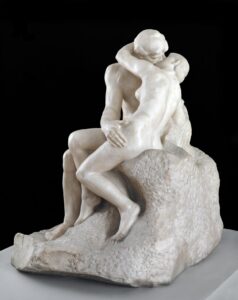

The Kiss, by Auguste Rodin

The poet’s own idealized yet bittersweet love was a favorite subject of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whose father was a Dantean scholar and who was in fact named after the Florentine poet. Rossetti used Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal and Jane Morris as models for Beatrice. In a case of life imitating art, Rossetti’s relationships with Siddal and Morris both ended unhappily. Rossetti painted Beata Beatrix after Siddal’s tragic death from an overdose of laudanum in 1862. The painting has various renditions, all placing the titular Beatrice (with Siddal’s characteristic red hair) in a beam of light, symbolizing her spiritual transfiguration. Later, Auguste Rodin’s famous 1880s sculpture “The Kiss” was originally titled “Francesca da Rimini.” The original pose was reportedly so passionate that it was censored at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair due to fears that it would incite “lewd behavior.” Rodin was eventually persuaded to change the monumental marble’s name. Yet Paolo and Francesca still appear in the bronze work “The Gates of Hell,” directly inspired by Dante’s Inferno.

Even 700 years after his death, Dante’s work remains highly prized. In 2017, three “tome-raiders” stole over £2 million worth of antiquarian books (over 160 items) from a London warehouse. The stolen property included a rare 1569 edition of The Divine Comedy. The thieves managed to evade the security system by entering the warehouse from above. They bored holes into the reinforced glass skylights and lowered themselves 40 feet on ropes, similar to the film Mission Impossible. The criminals likely received inside information on the location of the valuable books, leading to the heist. The international rare book market is worth approximately $500 million a year. Unfortunately, that means that thieves target valuable manuscripts for the illicit trade. Unfortunately, book theft has been on the rise. However, because of the notoriety of the stolen works, here the thieves’ options were to issue a ransom demand or attempt to sell the goods on the black market for a fraction of the price (5-10%). Fortunately, the books were recovered in Romania in 2020 before they were offered for sale. The crime was linked to various organized crime families with “a history of complex and large-scale high value thefts.”

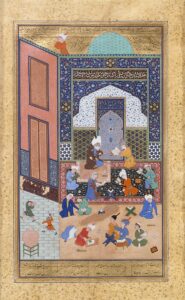

“Laila and Majnun in School”, Folio 129 from a Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami of Ganja. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Moving further east, the tale of Layla and Majnun served as inspiration for artists. While the story originated in Arabic, it passed into Persian, Turkish, and Indian languages, denoting its popularity. In the 7th century, Bedouin Qays ibn al-Mulawwah fell in love with Layla bint Sa’d. These feelings were reciprocated, although the intensity of Qays’ obsessive passion expressed through poetry won him the epithet Majnun (meaning “possessed” or “mad”). Layla’s family, concerned about this outrageous public conduct, married her to another man. Upon hearing the news, Majnun exiled himself to the desert and adopted an ascetic lifestyle. Layla eventually became ill and died – some say of heartbreak. Majnun was later found dead in the wilderness near her grave, after carving three verses of poetry nearby proclaiming his undying love for Layla.

This tale has been told and re-told countless times because its themes of love and loss are universal. Majnun predated Dante by over half a millennium, but both poets were changed by their love, seeking to transcend physical bonds and attain a perfect, spiritual love. One of the most recognized versions of Layla and Majnun comes from a narrative poem composed in 1188 by Persian Nizavi Ganjavi. The story made it as far as Azerbaijan. There it became the Middle East’s first opera in 1908 thanks to renowned composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov. A scene from the poem was even depicted on the reverse of commemorative coins minted in 1996 for the 500th anniversary of Fuzûlî’s life, who originally adapted the story into Azerbaijani in the 16th century.

Layla and Majnun continue to fascinate people. In 2007-2008, Harvard University Art Museums hosted an exhibition on the representations of Majnun in Persian, Turkish, and Indian painting. Several manuscripts have been reproduced online, allowing viewers to immerse themselves more fully in the colorful world of these tragic lovers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum of Art have a series of Iranian wall paintings depicting the couple, as well as illuminated folios showing how they fell in love at first sight. The Cleveland Museum of Art also has a painting of the lovers meeting in the wilderness, as does the British Museum. Depictions of Layla and Majnun are so esteemed that modern fakes have been created to dupe potential buyers.

An authentic illustration at Harvard, “Illustrated Manuscript of Layla and Majnun,” has an interesting past. It is an illustrated copy of Hamdi’s version of Laila and Majnun, penned in 1499. This Turkish work was styled after the work of Jami, the famed Persian poet. The copy at Harvard is not dated, but notes on the manuscript indicate that it was copied in or around 1579, and that the copy may have been intended for the grand vizier at that time. However, subsequent owners are a mystery, and the work bears the square and oval seals of other owners. The manuscript contains 123 folios containing text and seven illustrations. The last folio likely contained a colophon (a printer’s mark), but unfortunately it is lost— the book continues a replacement folio. In addition, the lacquer binding on the book is also not original; it probably belonged to a Qajar manuscript of the late 18th century from Iran. Interesting, the inner sides of the book covers have been reversed to serve as outside covers.

The volume was eventually found its way to France. It likely was sold in Paris by Jean Soustiel in the 1970s to Edwin Binney, 3rd, and it was eventually bequeathed to Harvard University Art Museum in 1985.

Provenance: [Jean Soustiel, Paris, possibly May 1975], sold; to Edwin Binney, 3rd, by 1977, bequest; to Harvard University Art Museum, 1985.

We hope you have enjoyed this foray into works of art inspired by love and passion.