by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 18, 2023 |

Asheville, NC is where tourists in October find a plethora of autumnal sights, including phantom ones. Not only is it peak-leaf season in the Blue Ridge, it’s also peak-ghost season at Biltmore Estate.

Biltmore House in Autumn. Image courtesy of R.L. Terry via Wikimedia Commons.

Biltmore House

Biltmore Estate, home to what is considered to be America’s largest residence, sits amidst the stunning grounds designed by famed landscaper Fredrick Law Olmstead. The curated gardens and rolling hills are the perfect backdrop for the home itself, which is truly a work of art. The home is an enormous, stately French Renaissance mansion designed by Richard Morris Hunt (New Yorkers will recognize Hunt as the genius behind the pedestal of the Statute of Liberty and the façade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Hunt outdid himself at Biltmore in the number of rooms behind its the grand exterior. No fewer than sixty-five fireplaces, thirty-four bedrooms, forty-three bathrooms, and one indoor pool can be found inside.

Hunt also made sure to create special spots for the family-in-residence to privately retreat. Specifically, for the man of the house, Mr. George Vanderbilt, Hunt inserted a large, luxurious library. This grandiose space housed 10,000 tomes, which George likely pretended to have read. There were many lively distractions on-tap at Biltmore, which may have prevented him from really digging into the books (these felicitous diversions will be explained below).

George’s Library at Biltmore House

Whether or not George actually read any of the books, the library was a favorite retreat for him. In modern parlance, it may be referred to as his “man-cave.” The library today feels a bit spooky, and with good reason. George’s ghost is reported to visit the room with alarming frequency.

Library at Biltmore House. Image courtesy of Warren LeMay via Wikimedia Commons.

Before George died his untimely death in 1914 from complications from illness (not COVID), he was known to take his leave in the library when he heard a thunderstorm approach. His ghost seems to have kept up the habit. When late-summer and autumn storm clouds gather over the Blue Ridge, it’s a safe bet George’s ghost is high-tailing it to his sacred library. Who knew ghosts were afraid of thunder and lightening? It’s a shame thundershirts only come in “living dog”-sizes.

George’s ghost is not the only paranormal presence to haunt the historic halls of Biltmore. Remember the raucous fun this post alluded to earlier? Biltmore was famous for throwing outrageous parties in its prime. With each party, the national press had a field day. It’s hard to detail what happened at these soirées without disclosing embarrassing information about the over-served guests. Suffice it to say that these get-togethers put Gatsby’s parties to shame.

The guests so enjoyed themselves at Biltmore parties in life, that many have returned posthumously to keep the fun going. Modern-day guests report hearing clinking glasses, bits of dance music, and glittering laughter in the halls. Ghosts getting handsy with their ghoul-friends? Sounds likely.

Halloween Room at Biltmore House

Biltmore contains another spooky secret, apart from the ghosts. The creepy and mysterious Halloween Room is aptly named for this time of year. It’s a room in the basement that regularly creeps out modern-day guests. A dark, damp tunnel opens into a dimly lit, cavernous room. Adorning the walls are not the luxurious fabrics and intricate tapestries seen upstairs. Down below, the walls are covered in murals of black cats, witches, and gross-looking bats.

Halloween Room at Biltmore House. Image courtesy of Warren LeMay via Wikimedia Commons.

For years, no one – not even the living heirs of the Vanderbilt and Cecil families – knew where these painted scenes came from. The room was simply called the Halloween Room, because it was assumed that the creepy paintings were leftover decorations from a Halloween party. An autobiography of a local man revealed the truth and solved the mystery: they were leftover decorations, but the party wasn’t for Halloween – it was for New Year’s!

This new source gave all the details. On December 30th, 1925, the theme for Night One of the New Year’s festivities was “vaudeville.” Evidently, vaudeville comedic acts and European cabarets were all the rage in Manhattan. The idea was to bring a piece of the mystery and glamour down South.

What resulted was a truly legendary bash – the Charleston Daily Herald reported that over one hundred guests attended, and partied either until they dropped, or till dawn (whichever came first). One guest went on the record and called it “The best party I’ve ever attended.” If that’s the case, no wonder he and other ghosts return to Biltmore. The living dead are still killin’ it on the dance floor in the Halloween Room (but no one was actually murdered there).

Music Room at Biltmore House

As if ghosts and creepy bat paintings weren’t enough, Biltmore houses an even more spectacular secret. Modern-day tourists learn this secret back on the first floor of the home, in the Music Room. It’s here that the National Gallery of Art hid the nation’s artistic treasures during WWII.

Music Room at Biltmore House. Image courtesy of Warren LeMay via Wikimedia Commons.

Fearing a Nazi air-raid attack on the nation’s capital, David Finley – then director of the National Gallery of Art – called Edith Vanderbilt to ask a favor. Finley had been a guest at Biltmore (lucky him!) and recalled both its remote location and fireproof construction features. This winning combo made it the perfect hideaway for some of the most precious works of art in the United States. Botticelli’s The Adoration of the Magi and Rembrandt’s Self-portrait were among the sixty-two paintings and sculptures tucked neatly behind steel-enforced doors.

Guests at Biltmore in 1942 had no idea that they were sleeping under the same roof as the nation’s most valuable pieces of art. It was only after the war that the secret stash at Biltmore was made public knowledge.

Biltmore House and grounds. Image courtesy of Don Sniegowski via Wikimedia Commons.

The Story Continues at Biltmore Estate

To learn more about Biltmore House, its secrets, and all of its haunted happenings, visit Biltmore Estate in-person this season. Go for the peak fall foliage and stay for the hard-partying ghosts. There’s even a famous winery on-site – and we hear the Boo-ze is free-flowing.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 26, 2023 |

Madonna in concert in 2005. Credit: David Cushing, https://www.flickr.com/

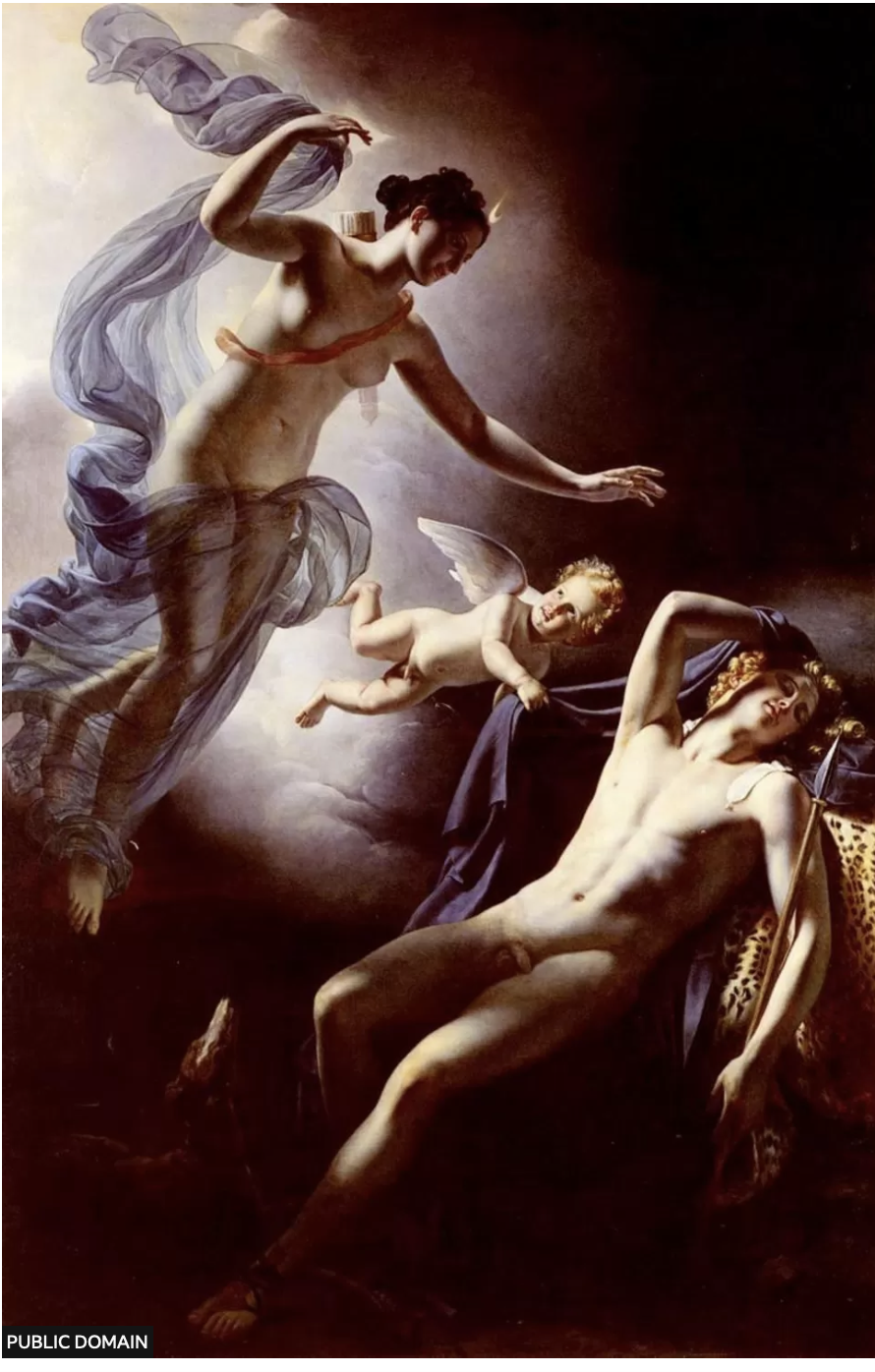

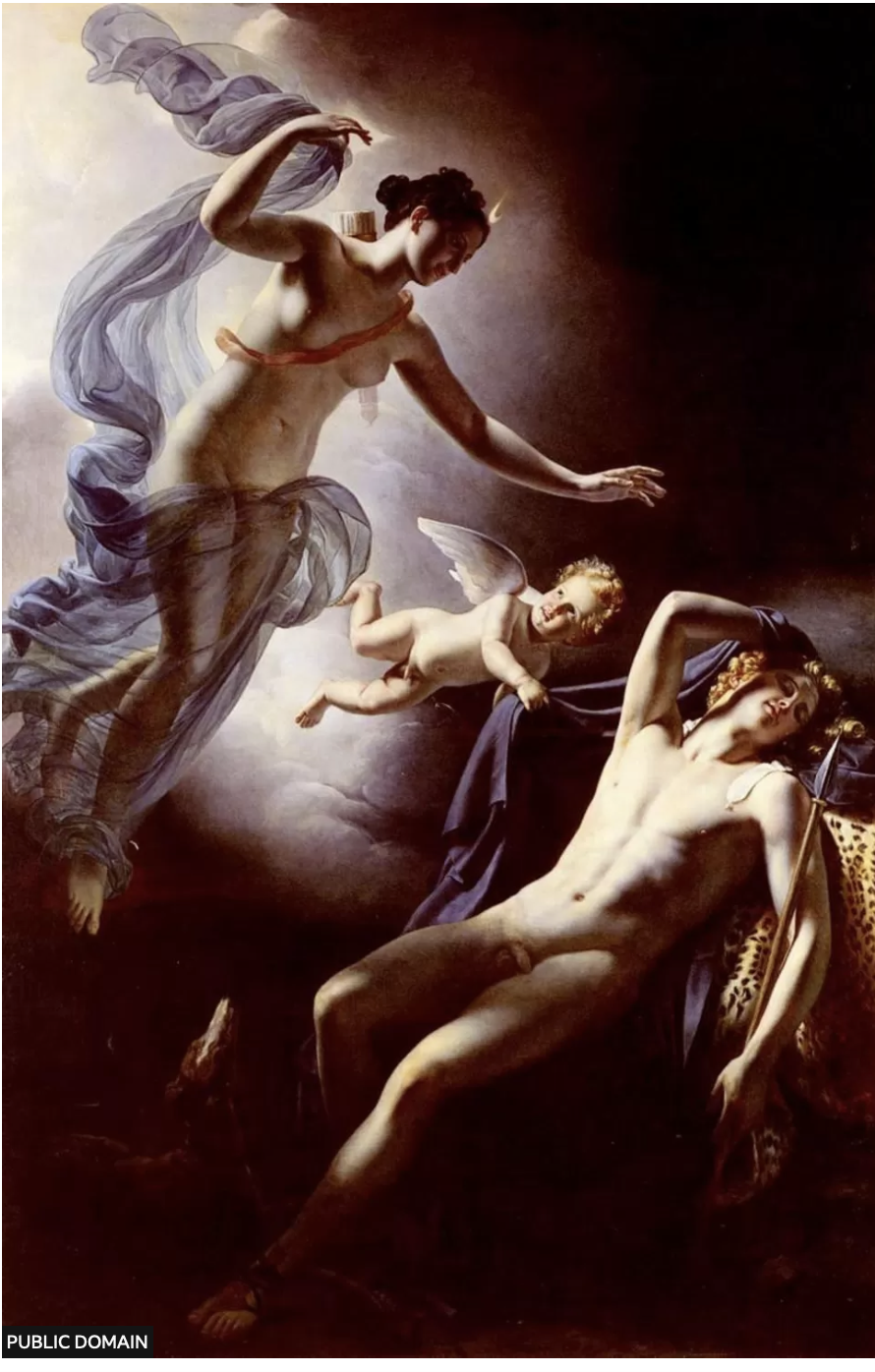

Madonna, singer of “Vogue” fame, has been asked to negotiate a loan of an 1822 Jerome-Martin Langlois painting from her personal art collection. The mayor of Amiens requested that the singer loan the work to the Musée de Picardie in the French city. The painting was purchased by Madonna in 1989 at auction, around the time that the singer’s fourth studio album was released. Decades later, in 2015, a museum curator recognized the painting after Madonna was featured in an issue of the weekly publication Paris Match Magazine. The article included a photograph of the “Material Girl” in her home, with the painting visible in the background.

When the curator examined the subject matter of the painting in the photo – a small Cupid in flight dashing between Roman mythological figures Diana and Endymion – a match was made. The painting looked remarkably similar to a work once owned by the Musée de Picardie and thought to have been destroyed by World War I bombings. Further inquiry revealed that the painting once thought lost is very likely the work hanging in Madonna’s home.

Notably, the city of Amiens has not accused Madonna of any wrongdoing, and it is not demanding the restitution of the work. Rather, the city has requested a loan. Such a deal could be fortuitous for both Madonna and the city of Amiens. Madonna would keep the painting in her private collection following the loan, and Amiens could display the painting in its original glory. Moreover, Amiens would no doubt benefit from the added publicity of a loan from such an A-list celebrity. This would be particularly timely for the city, coincidentally gunning to be named the Cultural Capital of Europe in 2028. (Amiens, among other cities such as Brovmov in the Czech Republic and Skopje in North Macedonia, are on the most recent short list for the recognition).

Diana and Endymion, Jérôme-Martin Langlois, 1822, Credit: Public Domain

Madonna has yet to respond to the loan request. Her decision whether to accept or reject the offer to negotiate might be influenced (hopefully, positively) by certain outcomes of other high-profile celebrities who have faced ownership claims against artwork held in their personal collections.

Other Celebrities With Problematic Art

One path for some has been to return the work outright. As we discussed previously, Nicolas Cage returned a dinosaur skull he bought at auction once it was established that it had been illegally excavated. Another 80s icon, Boy George, was keen to return a contested piece to its claimant owner. In 2011, the stylish singer returned an icon to Cyprus, to later be reinstalled in the Church of St. Charalambos. The church’s bishop saw the icon in the background of a video interview filmed in Boy George’s home. He recognized the piece as one stolen from the church following Turkish invasion in 1974. Boy George’s graciousness in returning the piece is heartening (he went on record as “happy [to see] the icon going back to its original home.”

Another path forward for celebrities with problematic artwork is to negotiate in good faith with the claimants, in lieu of lengthy and costly litigation. Take, for example, a piece put up for auction by the stewards of the late Gianni Versace’s private art collection. In 2010, a painting that once hung in Versace’s Lake Como villa was consigned for auction at Sotheby’s in London. The listing, a portrait by Johann Zoffany entitled Portrait of Major George Maule caught the eyes of the direct descendants of the painting’s owner. The descendants contacted the Art Loss Register, who negotiated with Sotheby’s. After what was reported as an amicable mediation, the piece was pulled from auction. The work was returned to its original owners, who were “overjoyed” to be able to hang the painting from their own walls.

Van Gogh’s Vue de l’Asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Remy, gracing the catalog cover for the sale of Elizabeth Taylor’s collection (Credit: Christie’s LLC)

Negotiating has also proven to be a feasible and mutually beneficial option for the Andrew Llyod Webber Art Foundation. After the Foundation put up a Picasso for auction at Sotheby’s in London, heirs of a Jewish family claimed that the work was sold under duress to the Nazi Party by their ancestor. In 2010, the parties reached an agreement of undisclosed terms (and, as the painting is valued at over $60 million, a substantial award was likely given to the family). Following the negotiations, the family willingly relinquished all ownership claims of the work, and seemingly walked away content with their end of the bargain.

However, some celebrities – either with the budget for litigation or incredibly personal ties to the contested work at issue (or both) – are willing to fight in court. Elizabeth Taylor is one example. She defended herself in litigation after she was contacted about a piece in her personal art collection in 2004. The 1889 work, a Van Gogh painting entitled View of the Asylum and Chapel at Saint Remy, was sold at auction to the actress at Sotheby’s in London in 1963. Decades later, descendants of a Jewish woman named Margarete Mauthner claimed that the painting was rightfully theirs. They asserted that it had been sold by their ancestor under duress by Nazis. The Orkin family sought redress under the 1998 U.S. Holocaust Victims Act, but was barred from recovery due to the statute of limitations. The 9th Circuit upheld the lower court ruling that the Orkin family had missed their chance to claim ownership, and Elizabeth Taylor kept her painting in her L.A. residence.

Amiens, France. Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collections, licensed via pingnews

Madonna’s Next Steps

Taylor’s unwillingness to relinquish ownership stands in contrast to the negotiations and settlement offers made by Versace and Andrew Llyod Webber’s Art Foundation. The potential for high-profile art buyers to avoid litigation and to instead reach amicable agreements presents a cooperative path forward and an overall more sustainable approach. These types of mediations, which may include the return of the work, give power and voice to claimants, without demonizing buyers who may have been unaware of the work’s problematic provenance. (This is particularly important in the case of celebrity buyers, who often work through intermediaries.) This ensures that justice is served, and that past traumas are recognized, while promoting the preservation and enjoyment of cultural heritage for generations to come.

The humanizing impact of high-profile celebrities who publicly acknowledge original ownership of a problematic work cannot be understated. When celebrities use their platform to give voice to people whose voices have been silenced, they set in motion healing work in the practicum of art and cultural heritage. What will Madonna do, moving forward? Perhaps she will be inspired to accept the loan offer and cooperate amicably with the City of Amiens.

After all, in the agreement put forth by Amiens, Madonna can still “keep her baby.”

.”

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 5, 2022 |

After the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. government began forcibly removing Japanese Americans from the West Coast and relocating them to isolated, inland areas. Around 120,000 people were detained in internment camps for the remainder of WWII. Among those interned were various artists – some were professional artists, some created works of art or crafts to occupy their time, and others used art to document their experiences during this uncertain time.

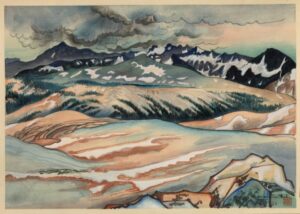

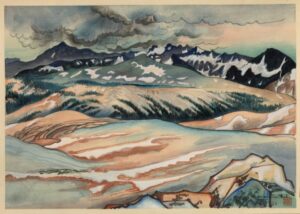

Chiura Obata, a notable artist and art teacher, was one such detained Japanese American artist. Last month, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) acquired thirty-five of Obata’s works created between 1934-1943, many of which were created during his internment in Utah.

Copyright: Archives of American Art, Chiura Obata Papers

Obata was a California-based artist who emigrated to the United States from Japan in 1903. After gaining notoriety early in his art career, Obata was named as a faculty member of the Art Department at the University of California, where he worked from 1932-1954. However, in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attacks, Obata and his family were relocated from their California home and interned. They were first sent to the Tanforan Detention Center (located in the Bay Area) and then to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah.

During his internment at each detention center, Obata served as a leader in creating art schools for detainees like himself. In addition to teaching, Obata created some 350 works during this period. These works included large-scale paintings of the landscapes surrounding the camps, drawings for the camp’s newspaper, and watercolors and sketches that documented life as a detainee (given that cameras were not permitted, artworks were used to create a record of daily life). Obata wished to show that he and his countrymen had not been defeated by the prejudice and humiliations they suffered.

Today, Obata is known for his brush and ink landscapes and portraits of America, in which he blends traditional Japanese brush styles with traditional Western techniques. Despite his time in the camps, Obata’s work shows a fascination with and focus on the rugged beauty of American landscapes, at odds with the ugliness of the detainment centers. He was able to find “the beauty that exists in enormous darkness.” The collection at the UMFA was donated by the Obata Estate. Representatives of the estate hope that “people will be inspired to learn the history of wartime incarceration and go visit the actual camp site in Delta as well as the Topaz Museum,” after viewing the pieces at the UMFA.

Chiura Obata, Great Nature, Storm on Mount Lyell from Johnson Peak, 1930, color woodcut on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Obata Family, 2000.76.8

Copyright: Lillian Yuri Kodani, 1989

In addition to this new collection, Obata has been featured in several exhibits and his works are in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, the Smithsonian, and other well-known institutions.

Art created during this period of internment, however, went beyond Obata’s contributions. Many Japanese Americans had been artists previously or found solace in art during this period. George Matsusaburo Hibi was another notable artist interned with Obata. The two men worked together while at the Tanforan Assembly Center to create an art school, which eventually enrolled 600 students.

Before internment, Hibi was a student at the California School of Fine Arts. Throughout the 1930s, Hibi’s work was exhibited in the San Francisco area, and was even exhibited at the Oakland Art Gallery in 1943 while he was still interned in the camps. Hibi is primarily known for his printmaking and oil paintings. Many of his works depict the bleak aspects of the camp, including the harsh winters.

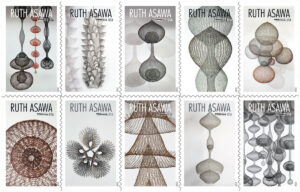

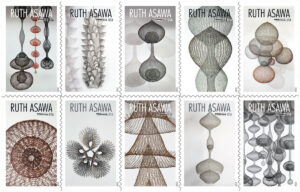

2020 Stamps honoring featuring Ruth Asawa’s art. Copyright: 2020 U.S. Postal Service.

Other notable interned artists were ones that worked as animators for Walt Disney Studios, including Tom Okamoto, Chris Ishii and James Tanaka. Like Hibi and Obata, these cartoonists also used their time at the internment camps to teach art. One of their students was Ruth Asawa, a young girl who had not previously explored art. While interned, however, she found free time to draw and explore her creative talents. Today, Asawa is a renowned artist with works in the Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum in New York. She is known for her wire sculptures and the fountains she was commissioned to create in San Francisco. In 2020, the U.S. Postal Service honored her by featuring her art on a series of stamps.

During WWII, American Japanese internment camps were not the only camps that detained artists. In Nazi Germany, millions of people were forcibly interned. The circumstances and treatment of the prisoners at these camps varied, but in some cases, they were significantly crueler and more repressive. Unlike the U.S. internment camps, many Nazi camps were a mechanism to kill people. However, like the U.S. internment camps, they provided an unlikely source of inspiration and solace.

One famous artist who emerged from the camps was Kurt Schwitters. Schwitters had had gained renown as an artist for his involvement in the Dada movement, but in 1940 he was placed in a camp on the Isle of Man. Like the interned Japanese American artists on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Schwitters created art in a studio and used his time to teach other prisoners, some of which became successful artists in their own right. However, creating and teaching art were not easy for Schwitters. Given the circumstances in the camps, art supplies were scarce. This forced Schwitters and other artists to become resourceful and find alternate tools to create art. People at the camp with Schwitters recall that he pulled up the linoleum flooring to paint on and even made a sculpture out of his porridge. Regardless of these obstacles, Schwitters produced over 200 works while at the camp. To honor these works and Schwitters’ legacy, a gallery near where he was interned exhibited his work. It attracted thousands of visitors in 2013.

Other works by imprisoned artists are honored at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum is located at the site of the site of the former concentration camp and has a gallery with over 2,000 works of art that were created by prisoners at the various Nazi camps. In some of the more restrictive Nazi camps, art and any tools needed to create art were forbidden. Rather, works created in these camps were prepared in secret and using whatever supplies detainees could find. Many of the works were created to defy the Nazis and expose and document the atrocities occurring in the camps.

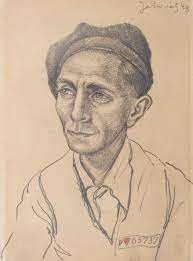

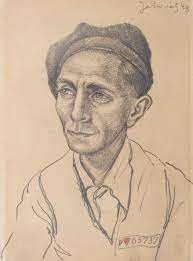

Drawing by Franciszek Jaźwiecki

Photo Credit: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Famously, Polish artist Franciszek Jaźwiecki secretly created a historical record through his portraits. An art historian at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum believes that he drew these portraits for the purpose of creating a historical record, given that he included the prisoners’ numbers in each of his portraits. This has allowed historians to attach a name to the portraits through the number. Jaźwiecki took a huge risk by creating these drawings, as it was strictly prohibited. Records reveal that he hid his portraits in his bed or in his clothes. The portraits survived and after his death, his family donated 100 of his works to the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in remembrance of his experience.

Many other such works and photographs have been uncovered. Historians believe that, like Jaźwiecki’s portraits, they were being used to document the people, conditions, and events in the camps. On display at the museum is a sketchbook with 22 pictures by an unknown artist. During his time at Auschwitz, he secretly drew the exterminations of detainees. His drawings were found in 1947 in a bottle that had been hidden in the foundations of a building near Birkenau’s crematoriums. This sketchbook is the only artwork uncovered that documents the extermination at Birkenau.

While internment camps are a difficult part of history, the art that was produced there reflects and documents this era. Art was both a practical tool for prisoners to occupy their time, but also contribute to newsletters and document the people and circumstances of the camps. It was additionally an emotional tool to help prisoners distract from their realities, retain their identity and purpose, and in many cases, to expose and cope with the bleak environments in which they were detained.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jan 14, 2017 |

The Art Newspaper recently reported that the long-held freeze on museum loans between Russian and U.S. museums could finally come to an end.

The Art Newspaper recently reported that the long-held freeze on museum loans between Russian and U.S. museums could finally come to an end.

In December, both the Senate and President Obama approved the Foreign Cultural Exchange Jurisdictional Immunity Clarification Act. The Act is intended to protect artworks and culturally significant objects on temporary loan to the United States from foreign institutions, by granting those artworks immunity from seizure.

Director of the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Mikhail Piotrovsky, openly praised the Act to The Art Newspaper, noting that the law could potentially provide new assurances that Russian-owned artworks would not be subject to seizure while in the United States. Piotrovsky’s statements came while visiting his long-time friend President-elect Donald J. Trump at his Florida home in December. Trump himself has been very vocal about his intent to warm US-Russian relations, so the possibility of seeing Russian-owned artworks once again in the U.S. could become very real after his January inauguration.

The new law has nevertheless faced heavy criticism from groups including the Holocaust Art Restitution Project. Although objects subject to Nazi-era restitution claims are not afforded protection under the Act, critics point out that the new Act could extinguish valid restitution claims, such as claims against the Russian and Cuban governments.

The Russian government suspended all artwork loans to US museums in 2011, fearing that any loaned artwork could be seized as part of an outstanding court order requiring Russia to turn over a vast library of religious texts to the Chabad-Lubavitch Orthodox Jewish community. In 2010, a federal judge in Washington had ordered that the Russian government turn over the “Schneerson Library,” a collection of more than 70,000 religious texts and documents to the Chabad organization. The organization has been trying to regain possession of the library for years, which was seized by the Bolsheviks during World War II, and Russia has yet to return the documents. In response to Russia’s cancellation of museum loans to the United States, US museums have also frozen lending artworks to museums run by the Russian government.