Exploring Women’s Unsung Contributions to Art

In honor of International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month, our firm is reposting one of our favorite blog posts. This post originally ran on our firm’s blog in 2021.

—

It is a bitter truth that women, who are so often depicted, admired and romanticized through art, have had to overcome herculean obstacles to participate in its creation. In honor of Women’s History Month, this entry in our Provenance Series examines the work of the Old Masters’ female counterparts – the Old Mistresses – and their contemporary successors.

Rediscovery of Female Artists

Renaissance and Baroque works by women have deservedly entered the public consciousness in recent years. In 2019, a depiction of the Last Supper by nun Plautilla Nelli was installed in the Santa Maria Novella Museum in Florence, after a painstaking 4-year restoration by the Advancing Women Artists Foundation (AWA). The project was made possible through the AWA’s “adopt an apostle” crowdsourcing program: private financiers were allowed to “adopt” one of the life-sized disciples at $10,000 each (ever-unpopular Judas was instead funded by 10 backers at only $1,000 each). The oil painting, measuring 21 feet across, is one of the largest Renaissance works by a female artist still in existence. It is also the only work created by a woman during the Renaissance depicting the Last Supper.

Last Supper by Plautilla Nelli (prior to restoration). Image via My Modern Met.

The Provenance and Restoration of Plautilla Nelli’s The Last Supper

The Last Supper was likely created for the benefit of Plautilla’s own convent, the convent of Santa Caterina di Cafaggio in Florence, where it hung in the refectory (dining hall) until the Napoleonic suppression in the 19th century, when the convent was dissolved. It was thereafter acquired by the Florentine Monastery of Santa Maria Novella in 1817. Again, it was housed in the refectory until being moved to a new location in 1865. Scholar Giovanna Pierattini reports it was moved to storage in 1911, where it remained until 1939. It then underwent significant restoration, and returned to the refectory. It would remain on display there for almost forty years, surviving the historic flood of the Arno in 1966 with little damage. The work was next taken down in 1982, when the refectory was reclassified as the Santa Maria Novella Museum, and transferred to the friars’ private rooms. This is how the monumental work, which remained out of the public eye for centuries, is now visible to the public for the first time in 450 years.

Rossella Lari, the restoration’s head conservator remarks, “We restored the canvas and, while doing so, rediscovered Nelli’s story and her personality. She had powerful brushstrokes and loaded her brushes with paint.” The painting features emotionally charged expressions, emphatic body language, and exquisite details, such as the inclusion of customary Tuscan cuisine (roasted lamb and fava beans).

Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy. Image courtesy of CAHKT/iStock.com.

Plautilla’s use of color and composition is even more impressive when one considers that women were barred from attending art schools and studying the male nude; instead, they were forced to rely on printed manuals and the works of other artists. Plautilla was not only a self-taught artist, but she also ran an all-woman workshop in her convent and received the ultimate praise for an Italian Renaissance painter: inclusion in Giorgio Vasari’s seminal book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Notably, in Plautilla’s time the convent was managed by Dominican friars previously under the leadership of fire-and-brimstone preacher Girolamo Savonarola. The nuns were encouraged to paint devotional pictures in order to ward off sloth.

Undeterred, “Plautilla knew what she wanted and had control enough of her craft to achieve it,” says Lari. The Last Supper is signed “Sister Plautilla – Orate pro pictora” (“pray for the paintress”). Plautilla thus confirmed her role as an artist while acknowledging her gender, understanding that the two were not mutually exclusive. Although only a handful of the works survive today, Plautilla and her disciples created dozens of large-scale paintings, wood lunettes, book illustrations, and drawings with great focus, determination, and discipline. She is considered the first true woman artist in Florence and in her heyday, “There were so many of her paintings in the houses of gentlemen in Florence, it would be tedious to mention them all.” Since AWA’s conservation work was initiated, the number of works attributed to Plautilla has risen from three to twenty, meaning that other undiscovered masterpieces could be lying in wait.

Female-Led Museum Exhibitions

The Prado Museum in Madrid has hosted an exhibition featuring two overlooked Baroque painters, Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana, in an exhibition entitled “A Tale of Two Women Painters.” Meanwhile, the National Gallery in London hosted a show dedicated to Artemisia Gentileschi. Notably, Sofonisba, Lavinia and Artemisia all achieved fame and renown during their lifetimes, including royal commissions, only to be eclipsed for centuries after their deaths. Sofonisba was particularly sought after for her ability to capture the expressiveness of children and adolescents in intimate portraits, while Lavinia’s commissions displayed a more formal Mannerist style. Artemisia, the subject of the National Gallery’s first major solo show dedicated to the artist, is recognized as much for the strength of her figures in chiaroscuro as for her life story involving sexual assault and trial by torture. Despite considerable difficulties, Artemisia was able to succeed in a male-dominated field and created over 60 works, most of which feature women in positions of power. Artemisia is now hailed as one of the most important painters of her generation and an established Old Mistress in her own right.

Female Artists at Auction

Despite their long slumber in the annals of history, these artists are not only receiving attention in museums, but in auctions as well. In 2019, a painting by Artemisia depicting Roman noblewoman Lucretia shattered records when it sold for more than six times its estimated price at Artcurial in Paris. While estimates originally placed the work at $770,000 to $1 million, the painting was ultimately acquired by a private collector for $6.1 million. Lucretia was discovered in a private art collection in Lyon after remaining unrecognized for 40 years. It was in an “exceptional” state of conservation according to Eric Turquin, an art expert specializing in Old Master paintings previously at Sotheby’s.

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Lucretia (ca. 1630-1640). Image via Getty Museum.

The earlier record for one of Artemisia’s works had been set in 2017, when a painting depicting Saint Catherine sold for $3.6 million. That painting, a self-portrait of the artist, was then acquired by the National Gallery in London for $4.7 million in 2018. This was the first painting by a female artist acquired by the National Gallery since 1991, and the 21st such item in its entire collection, which encompasses thousands of objects. Saint Catherine had been owned by a French family for decades, but its authorship was obscured prior to its rediscovery and sale by auctioneer Christophe Joron-Derem. The painting was acquired by the Boudeville family in the 1930s, but the exact circumstances of this acquisition and the painting’s prior whereabouts were unclear. At the time of the National Gallery’s purchase, museum trustees raised concerns that the work might have been looted during World War II, although there is no firm evidence to support this suspicion. Despite the gaps in the works’ provenance, it was ultimately determined that the painting had been with the family for several generations and Saint Catherine was welcomed to her new home in London.

Recent Attributions

More recently, a painting of David and Goliath was attributed to Artemisia after a conservation studio in London removed layers of dirt, varnish and overpainting to reveal her signature on David’s sword. While the work’s attribution occurred too late for inclusion in the National Gallery exhibition, the owner is apparently delighted to discover the work’s true author and is keen to loan it to an art institution so the public can enjoy the work. This painting was originally acquired at auction for $113,000 and may have been owned by King Charles I – quite an esteemed pedigree and sure to raise its value by a considerable amount.

Artemisia Gentileschi, David and Goliath. Image courtesy of Simon Gillespie Studio.

In contrast to Artemisia’s ascendance, a painting once attributed to her father Orazio Gentileschi is now embroiled in controversy. That painting, which also depicts David and Goliath and described as “stunning” by the Artemisia show curator, has links to notorious French dealer Giuliano Ruffini. Ruffini is the subject of an arrest warrant due to his connection with a high-profile Old Master forgery ring operating in Europe. It is believed that the forgery ring, uncovered in 2016, garnered $255 million in sales, including works represented as being by Lucas Cranach the Elder and Parmigianino.

Although these paintings were widely accepted as genuine masterpieces and fooled leading specialists, they did not have verifiable provenances. The paintings were said to belong to private collector André Borie, although that was not the case and Sotheby’s was forced to refund money to buyers once the fraud came to light. The Gentileschi in question had been “discovered” in 2012 and sold to a private collector, who loaned it to the National Gallery in London. At that time, the painting was praised for its “remarkable” lapis lazuli background, but the museum did not conduct a technical analysis before displaying the piece. Despite several warning signs – the painting’s recent entrance into the art market, its unusual material, its similarity to another Gentileschi painting held in Berlin, and the lack of published provenance – the museum stated that there were “no obvious reasons to doubt” the painting’s attribution.

The forgotten nature of some female artists demonstrates that their talents are not rare, but rather that they lack the opportunities and publicity that male artists often take for granted. Once their talent is amplified, female artists are capable of great things. This pattern continues today.

The Modern Struggles of Female Artists

As famous female artists lost to history capture the public eye, they are joined by female contemporaries who share a similar struggle against underrepresentation. Women’s contribution to modern and contemporary art is often exemplifiedby those with ties to established male artists: Mary Cassatt (who achieved recognition as an Impressionist in Paris through her relationship with Edgar Degas); Georgia O’Keeffe (who entered the public eye via her relationship to Alfred Stieglitz); and Frida Kahlo (introduced to the art world by her husband, Diego Rivera). This truncated view ignores the vast amount of creative output generated by women, and reinforces the notion that recognition must be made through a male lens, a view prevalent during Artemisia’s time. It is worth noting that Artemisia’s father Orazio Gentileschi was her teacher and facilitator in the Baroque art market. In fact, this attitude has denied countless female artists of their deserving places in the canon of art history. It has even enabled surreptitious artists to take credit for works by others.

Yayoi Kusama.

Image courtesy of Kirsty Wigglesworth.

Today, Yayoi Kusama is a household name. The world’s top-selling female artist, she is renowned for her peculiar polka-dotted paintings and sculptures, which command long lines at preeminent art institutions across the globe. Like many famous contemporary artists from the last century, she is strongly associated with a unique personal style, and recognized by her bright-red wig. Despite her phenomenal success, her position in the pantheon of notable contemporary artists was anything but assured. Born in the rural town of Matsumoto, Japan in 1929, Kusama was discouraged from pursuing a career; rather, she was encouraged to marry and start a family. Frustrated by the constant efforts to suppress her artistic aspirations, she wrote to the already famous Frida Kahlo for advice. Kahlo warned that she would not find an easy career in the US, but nevertheless urged Kusama to make the trip and present her work to as many interested parties as possible.

Unsurprisingly, Kahlo’s advice was accurate. After traveling to New York, Kusama’s early work received praise from notable artists Donald Judd and Frank Stella, but it failed to achieve commercial success. Her work also attracted the attention of other renowned artists, who were able to channel ‘inspiration’ from Kusama’s work right back into the male-dominated New York art market. Sculptor Claes Oldenburg followed a fabric phallic couch created by Kusama with his own soft sculpture, receiving world acclaim. Andy Warhol repurposed her idea of repetitious use of the same image in a single exhibit for his Cow Wallpaper. Most blatantly, after exhibiting the world’s first mirrored room at the Castellane Gallery, Lucas Samaras exhibited his own mirrored exhibition at the Pace Gallery only months later. Needless to say, these artists did not credit Kusama for her work and originality. This ultimately caused a despondent Kusama to abandon New York and return to Japan.

Kusama spent the next several decades largely in obscurity. The frustrations in her career resulted in multiple suicide attempts and long-term hospitalizations. However, Kusama always found a way to channel this energy back into her art, and she continued to create art in various formats as a way to heal. It was not until a 1989 retrospective of her work in New York and an exhibition at the 1993 Venice Biennale that the world truly tok notice of her work. This global reintroduction was enough to galvanize interest in her artistic creation, leading to the success she enjoys today. While it may seem just that such a talented artist would eventually receive recognition for her work, this is not always a given and Kusama’s near erasure from the art world should not be discounted.

The Gendered Art Market Divide

In today’s art market, artists, collectors, dealers, and museums are making a concerted effort to fight this type of erasure. Kusama stands as a beacon to others, demonstrating that female artists can reach the pinnacle of their profession. However, it remains an arduous career path for many. Statistical analysis confirms that female artists are underpaid and underrepresented in both the primary and secondary art markets. For example, compare the highest price paid for a work by a living artist by gender: Jeff Koons’ Rabbit sold for $91.1 million in 2019; while Jenny Saville’s Propped sold for $12.5 million that same year, a mere 14% of the Koons’ price. Some of this disparity can be explained by the difference between men and women’s treatment in the workplace generally, but the art world is also subject to a number of particularities. Attributed to a host of causes, perhaps none is more prominent than women’s almost total exclusion from studio art until the 1870s. The art world has existed in this environment for so long that its institutions and relationships now mechanically reinforce the disparity between genders: women are less likely to receive recognition and training, and buyers are less interested in art created by females. The interest in female-made art is also disproportionality concentrated on its biggest names; the top five best-selling women in art held 40% of the market for works by women auctioned between 2008 and 2019. It has become a self-sustaining cycle that can only be broken through deliberate and effective action.

Initiatives Supporting Female Artists

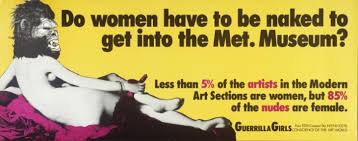

Artists and galleries have been working to shine a light on the current landscape of inequality in the market. Groups like the Guerilla Girls have used their cultural status and notoriety to vocalize issues regarding sexism, racism, and other types of discrimination still rampant today. This type of radical-meets-reformer message resonates with a newer generation that is more vocal about addressing discrimination, and frustrated by the seemingly lackluster efforts to minimize their impact on society. In honor of Women’s History Month, several galleries have announced shows dedicated to addressing some of these issues. The Equity Gallery is presenting “FemiNest,” a collection of works by female artists centered around the literal and metaphorical ideas conjured by the idea of a “nest.” The show explores in sculpture, textiles, painting and other media the new spaces that have opened for women in recent decades and their practical and spiritual impact for women. The Brooklyn Museum has announced a retrospective of Marilyn Minter’s work titled “Pretty/Dirty” aimed at challenging traditional notions of feminine beauty. Featuring more than three decades of work, the show will track Minter’s progress throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. The show is also part of a larger series of ten exhibitions by the Brooklyn Museum dedicated to the subject: “A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum.” Lastly, the Zimmerli Art Museum will feature an exhibition of works by the Guerilla Girls and other female artists who have worked to depict women’s unequal treatment in the art world, “Guerrilla (And Other) Girls: Art/Activism/Attitude.” (For more information about these shows and others addressing similar issues, see here.)

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? (1989), Guerrilla Girls. Image via the Met.

Although artists and art institutions have just begun the work of winding back centuries of discrimination, there is evidence that their work is already affecting the market. The percentage of female-generated artwork in the secondary market is increasing from year to year; from 2008 to 2018, the market more than doubled from $230 million to $595 million. Similarly, representation of women at major art shows is steadily, if inconsistently, increasing as well. This subtle shift in the market has been attributed at least in part to a new class of art purchaser: independently wealthy women, whose capital is self-made rather than inherited or shared via marriage. This novel source of demand is less sensitive to the traditional pressures of the market and is helping to fuel demand for works by female artists. Women’s History Month is an opportunity to reflect on the tremendous progress made by remarkable individuals in the art world, and to also contemplate the ripe opportunities that still lie ahead.

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has recently been featured in New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine, alongside other leaders in her field. Leila was chosen for the piece as a top-rated intellectual property, art, and cultural heritage lawyer well-known in the industry for getting the job done right. This means advocating both for her clients, and for the art and cultural heritage at issue.

Our founder, Leila Amineddoleh, has recently been featured in New York Metro Super Lawyers Magazine, alongside other leaders in her field. Leila was chosen for the piece as a top-rated intellectual property, art, and cultural heritage lawyer well-known in the industry for getting the job done right. This means advocating both for her clients, and for the art and cultural heritage at issue. As art fairs cautiously return and the auction season gears up, increased sales and acquisitions warrant a re-examining of due diligence in art transactions, both online and in real time. According to best practices suggested by non-profit initiative RAM (the Responsible Art Market initiative), “due diligence” is commonly defined as “action that is considered reasonable for people to be expected to take to keep themselves or others and their property safe”.

As art fairs cautiously return and the auction season gears up, increased sales and acquisitions warrant a re-examining of due diligence in art transactions, both online and in real time. According to best practices suggested by non-profit initiative RAM (the Responsible Art Market initiative), “due diligence” is commonly defined as “action that is considered reasonable for people to be expected to take to keep themselves or others and their property safe”. Depending on the collecting category, country of origin or materials may pose serious issues regarding the looting and illicit trafficking of cultural property. An artwork or object originating from known “source nations,” such as Greece or Italy, along with areas of increasing concern, such as Iraq and Syria, may be subject to trade restrictions. Items that were known to be in Europe between 1933 and 1948, in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union during the Communist era (between 1949 and 1990) or in Cuba during the revolutionary period (between 1953 and 1959), to name only a few, should be screened for potential title disputes. Also, some artworks incorporate restricted materials or material from endangered species, such as ivory or snakeskin, which may prohibit their legal trade.

Depending on the collecting category, country of origin or materials may pose serious issues regarding the looting and illicit trafficking of cultural property. An artwork or object originating from known “source nations,” such as Greece or Italy, along with areas of increasing concern, such as Iraq and Syria, may be subject to trade restrictions. Items that were known to be in Europe between 1933 and 1948, in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union during the Communist era (between 1949 and 1990) or in Cuba during the revolutionary period (between 1953 and 1959), to name only a few, should be screened for potential title disputes. Also, some artworks incorporate restricted materials or material from endangered species, such as ivory or snakeskin, which may prohibit their legal trade. A rarely seen painting by Vincent van Gogh will be auctioned at

A rarely seen painting by Vincent van Gogh will be auctioned at  Keeping pace with the artist’s rising popularity, the value of Vincent van Gogh’s art rose dramatically decades after his death. Sales of his works through auction have broken records numerous times in the 1980s and the 1990s. Lawsuits concerning his works have made the news for decades now. Five years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court

Keeping pace with the artist’s rising popularity, the value of Vincent van Gogh’s art rose dramatically decades after his death. Sales of his works through auction have broken records numerous times in the 1980s and the 1990s. Lawsuits concerning his works have made the news for decades now. Five years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court