by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Sep 1, 2022 |

A visit to the National Archaeological Museum of Taranto (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto, MArTA) reminded me why I love museums so much. It is an inspiring place, a valuable educational resource, and an underappreciated repository for art and heritage.

Taranto, Italy

Greek ruins (Temple of Poseidon)

MArTA is located in Taranto, a city located along the inside of the “heel” of Italy in the region of Puglia. It was founded by Spartans in 706 BC, and it became one of the most important cities in Magna Graecia (the Roman-given name for the coastal areas in the south of Italy — Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily — heavily populated by Greek settlers). Two centuries after its founding, it was one of the largest cities in the world with a population of around 300,000 people. Taranto (called Tarentum by the Ancient Romans) was subject to a series of wars, culminating in its fall to Rome in 272 BC. The city fell to Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but was recaptured (and subsequently plundered) by Rome in 209 BC. The following centuries marked the city’s decline.

Cathedral of San Cataldo

Taranto’s mix of architecture and rich cultural heritage is due, in part, to subsequent changes in leadership between the 6th and 10th centuries AD, during which time it was ruled by diverse groups: Goths, Byzantines, Lombards, and Arabs. Later, during the Napoleonic Wars in the 19th century AD, the city served as a French naval base, but it was ultimately returned to the Kingdom of Two Sicilies for a few decades before it officially became part of the Republic of Italy in 1861.

Due to its strategic location on the inlet of the Gulf of Taranto, the city has great naval importance. Taranto served the Italian navy during both World Wars. As a result, it was heavily bombed by British forces in 1940 (the bombing of Taranto and was even noted to have “set the stage for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor” the following year). The city was also briefly occupied by British forces during WWII.

Evidence of the city’s various iterations is evident throughout its streets with impressive cultural sites, including the Greek Temple of Poseidon, the Spanish Castello Aragonese (built in 1496 for the then-king of Naples, Ferdinand II of Aragon), and the 11th century Cathedral of San Cataldo (Taranto Cathedral), where the remains of the city’s patron saint, Saint Catald, lie (he is believed to have protected the city against the bubonic plague). More recent architectural gems include Palazzo Galeota and Palazzo Brasini.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Taranto (MArTA)

Like the city where it is located, MArTA is a rich institution full of incredible treasures. Last month, I had the opportunity to visit MArTA in person. Sadly, the museum, and the city itself, tend to fall under the radar of tourists. It is unfortunate that this site escapes attention, because both Taranto and its vaunted museum are incredible.

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

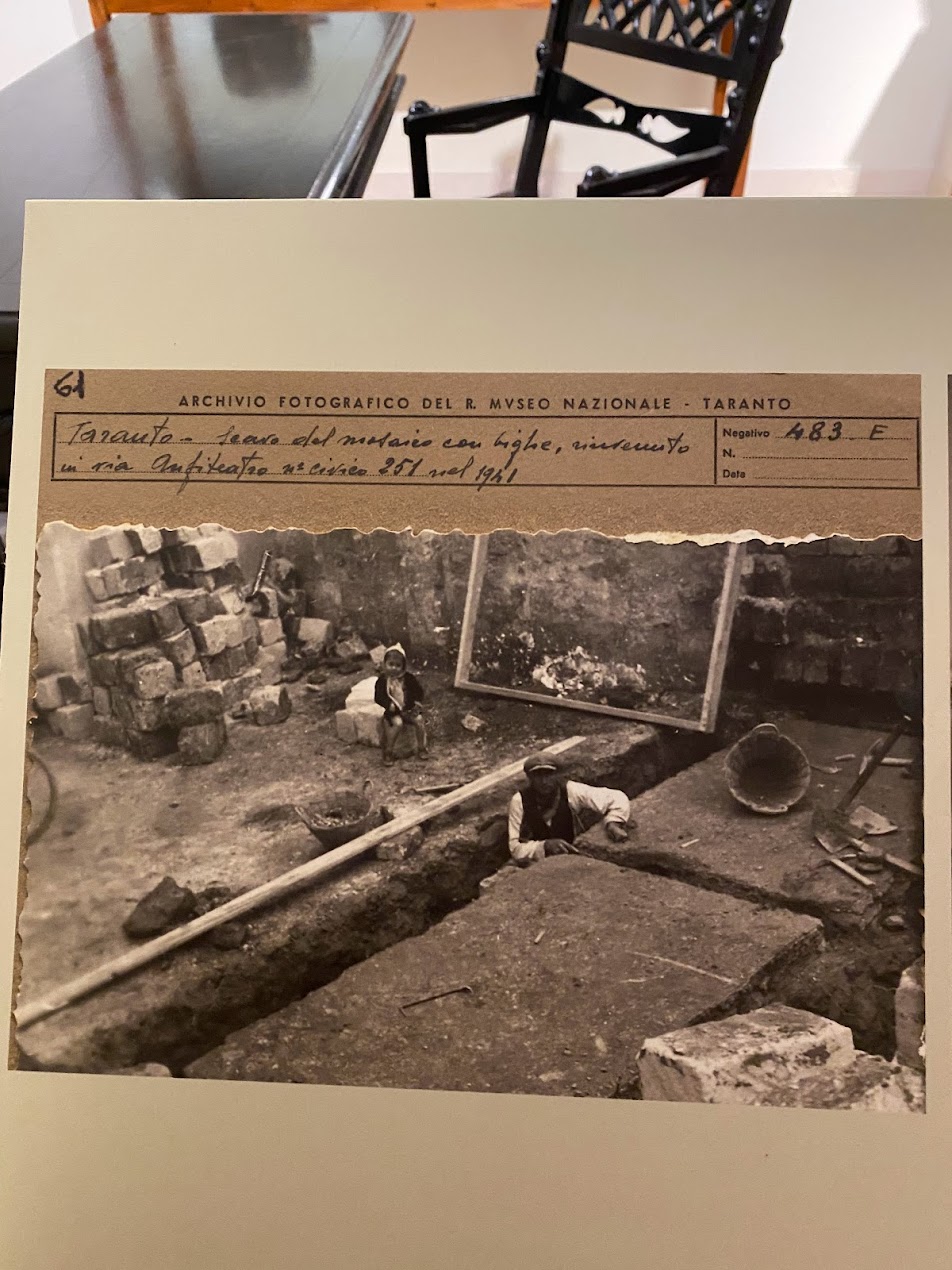

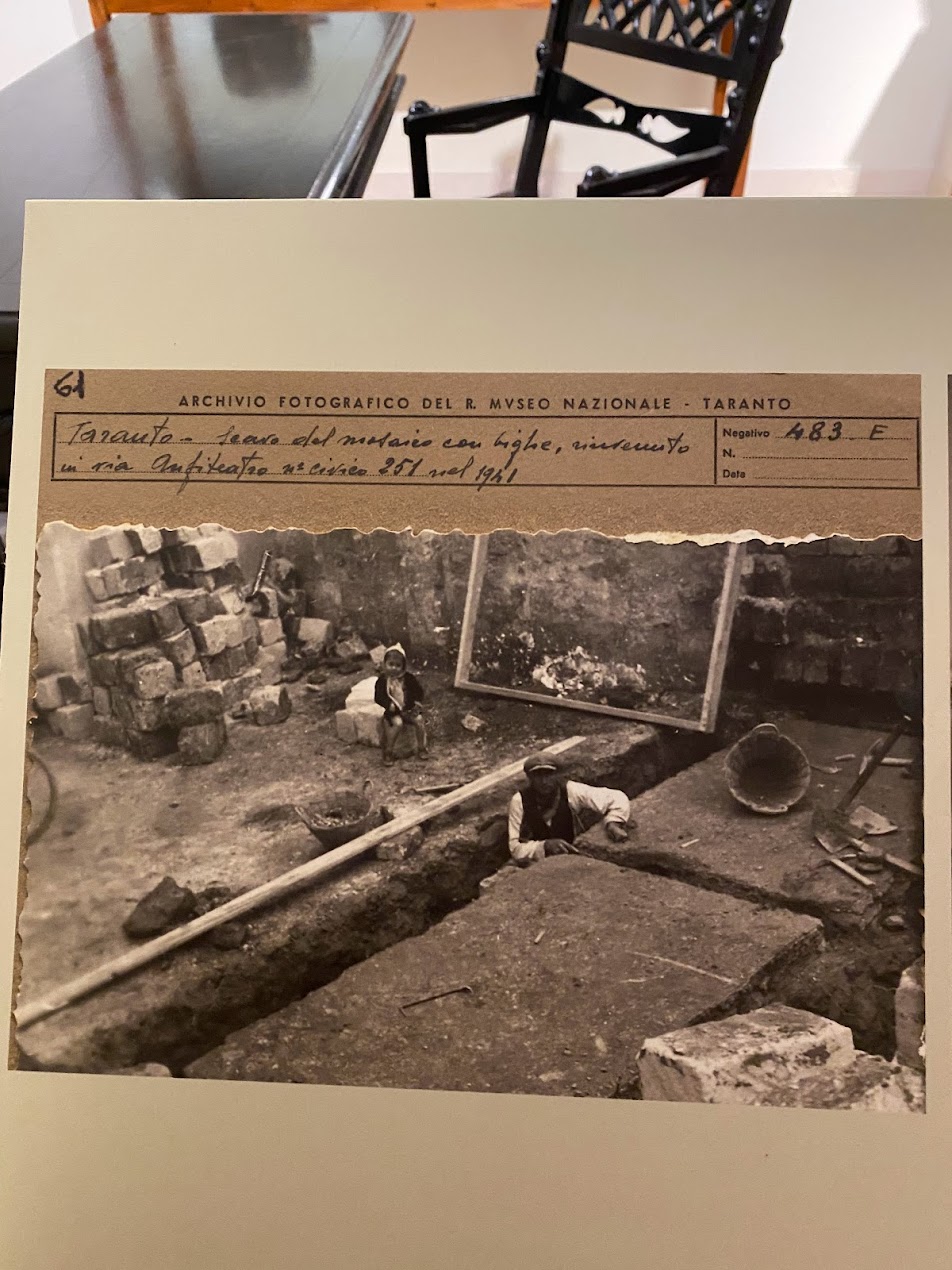

Amongst other treasures in MArTA are beautifully preserved mosaics, ornate golden jewelry, and ancient gold-covered snake skins. Another museum highlight are the informative displays positioning objects in creative contexts. For example, some objects are displayed along with photographic evidence and documentation about their excavation.

Tomb of the Athlete

The museum presents objects in beautiful vitrines. Some of the highlights on the first floor include thematic displays, such as a wall depicting Medusa’s face on antefixes found in Taranto. The curation includes information about the figure of Medusa in mythology and details on how her portrayal evolved over time. Another engaging display involves #italianmuseums4olympics, the Ministry of Culture’s campaign to support Italian sport and culture during the Olympic games. That particular display includes the sarcophagus of an athlete from Taranto, complete with amphorae found in his tomb that include images of athletic competitions, celebrating Italy’s long tradition of participating in the Olympics since antiquity.

An Apulian krater by the Darius painter returned from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2009

Looting of Objects on Display

As visitors enter the next floor of the museum’s route, they are confronted with a large restituted antiquity. A large Apulian krater by the Darius painter was returned to Italy in 2009 from the Cleveland Museum of Art after it was recovered by the Carabinieri’s TPC (the nation’s famed “Art Crime Squad”). The work was among fourteen artifacts returned from the Ohio museum after a two-year negotiation resulting from the investigation of a looting network run by Giacomo Medici and Gianfranco Becchina, two well-known dealers of looted materials who sold antiquities at auction and through dealers to supply coveted objects to collectors and museums around the world.

Loutrophoros restituted by the J. Paul Getty Villa in Malibu in California

MArTA also acknowledges some of the people responsible for the development of its exquisite collection, including past directors and donors. The displays note that the illicit or unknown sale of antiquities has led to the loss of knowledge about their historical and cultural value (when artifacts are illicitly excavated and divorced from their contexts, valuable information is lost in the process). However, the development of patrimony laws has allowed the Italian government to control more of the archaeological discoveries taking place, and other legislation has also encouraged collectors to donate their property to the museum and Italian State. The display also notes the important work by law enforcement and its success in having works repatriated to Italy, as well as its success in confiscating looted artifacts from private owners and collectors during the 20th and 21st centuries in Italy. Part of this display features works returned from major museums abroad, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Getty Museum in Malibu, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Labels and Information

The labels and information offered to visitors at the museum is exceptional, providing valuable information about the historic significance of items on display. Clearly, the museum places great importance on provenance, providing detailed information on where objects were excavated (this information includes exact find spots, with cross streets included for some of the objects), how they entered the museum’s collection, and ways in which the museum has evolved over the decades. Additional information is available to visitors about looting and criminal acts related to the objects, providing useful context.

Copy of the Goddess on Her Throne (the original is in Berlin)

One of the first objects to greet visitors upon their entry is a copy of a goddess on her throne. The original 5th century BC statue is “considered one of the greatest artworks from Magna Graecia.” It was found in 1912 in Taranto, but illegally exported out of Italy. It was then put on the Swiss art market, and finally purchased by the German government. It is currently on display at the Altes Museum in Berlin. Information like this is valuable, because it forces visitors to confront the political, societal, and cultural pressures facing museums, as well as the challenges and realities of the art and antiquities markets. It also provides a practical example of how works can wind up in international museums divorced from their original historical and cultural context.

As the museum’s website states, “The Museum also lends artefacts to other museums to allow global citizens to enjoy. We are aimed at providing first-hand information to all of our visitors so that they understand Europe’s prehistoric period.”

Castello Aragonese

A visit to this museum, and the gorgeous city of Taranto, with its sweeping coastal views, its rich cultural history, and its stunning architectural masterpieces, is essential for anyone visiting Puglia.

Copyrights in all photographs in this post belong to Leila Amineddoleh

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS

Objects from the museum’s early collection

Documentation of excavations

Vitrine (provenance information for each object is provided in a side panel)

Provenance on view

Beautiful entryways on each floor

Context with a photograph

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Oct 29, 2021 |

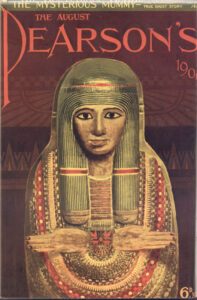

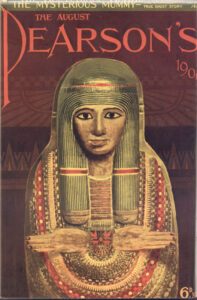

Cover of 1909 Pearson’s Magazine featuring the Unlucky Mummy

Just in time for Halloween, this spooky entry in our Provenance Series explores the strange case of the “Unlucky Mummy,” an ancient Egyptian artifact held by the British Museum since 1889 and rumored to have played a part in several tragic events during the last 150 years. The name of the object is misleading, as it is not an actual mummy, but rather a painted wooden “mummy board” or inner coffin lid depicting a woman of high rank. Mummy boards were placed on top of mummies, covered in plaster, and decorated elaborately with protective symbols of rebirth. The Unlucky Mummy was discovered in Thebes, an ancient hub for religious activity and the site of a renowned necropolis. It dates back to 950-900 B.C.E. While the lid does contain hieroglyphic inscriptions, these only refer to religious phrases; the identity of the deceased remains unknown. In the early 1900s, British Museum specialists believed that she may have been a temple priestess or a member of the royal family, but this was never confirmed by supporting evidence.

According to the museum’s records, the mummy board was originally acquired by an English traveler in Egypt during the 1860s-1870s. The mummy itself was most likely left in Egypt, since it has never formed part of the British Museum’s collection. The traveler was part of a group of Oxford graduates touring Luxor, who drew lots to haggle over the coffin lid. All four companions suffered unfortunate fates soon after this purchase. One of the men disappeared into the desert, one was accidentally shot by a servant and had his arm amputated, one lost his entire life’s savings, and one fell severely ill and was reduced to poverty. The mummy board then passed to the sister of one of the men, Mrs. Warwick Hunt, whose household became plagued by a series of misfortunes. When Mrs. Hunt attempted to have the coffin lid photographed in 1887, the photographer and porter both died, and the man hired to translate the hieroglyphs committed suicide. Clairvoyant Madame Helena Blavatsky allegedly detected an evil influence emanating from the mummy board, and convinced Mrs. Hunt to dispose of the object by donating it to the British Museum. Yet tales of the curse would follow. In 1904, journalist Bertram Fletcher Robinson published an article in the Daily Express titled “A Priestess of Death,” detailing the mummy board’s grisly exploits. When he died suddenly three years later, this was attributed to the Unlucky Mummy’s vengeance from beyond the grave. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and avowed spiritualist, claimed that the mummy’s spirit had used “elemental forces” to strike down Robinson.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and caused the ship to sink. However, this is only a rumor; the Unlucky Mummy has been on public display since the 1890s, except during WWI and WWII when it was placed in storage for safekeeping. It first left the British Museum in 1990 for a temporary exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia, and it made it back to London safe and sound. In fact, much of the mummy’s malevolent backstory was invented by English editor William T. Stead, who possessed a fascination with the supernatural. Ironically, Stead perished on the Titanic – but the Unlucky Mummy’s legacy lives on. It is allegedly responsible for multiple murders, illnesses, injuries, hauntings, eerie noises, flickering lights, and other suspicious activity.

For those who wish to see the Unlucky Mummy in person, it is currently located in Room 62 of the British Museum. Hopefully, its curse won’t follow you home…

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | May 3, 2018 |

Photo courtesy of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

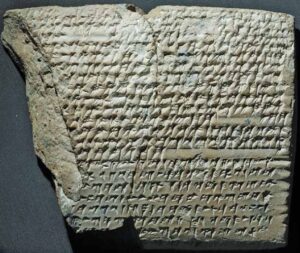

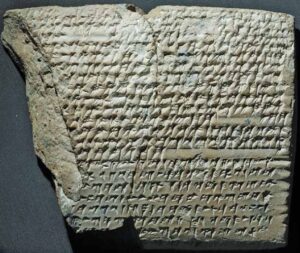

Our founder, Leila A. Amineddoleh, served as a cultural heritage law expert for the Eastern District of New York in its case against Hobby Lobby. The national retail chain, Hobby Lobby, purchased over 5,500 ancient artifacts from dealers in the Middle East, after one of the world’s legal heritage experts, Patty Gerstenblith, warned the company about acquiring objects lacking clear provenance. She warned the company that classes of objects from Iraq (including cuneiform tables) have a high probability of being looted from archaeological sites. Ignoring the advice, the company moved forward with the purchases anyway, and the plundered artifacts (bearing shipping labels with falsified information) entered the US illegally.

Yesterday, nearly 4,000 of the pieces were returned to Iraqi officials at the embassy. These objects will most likely be displayed at Iraq’s National Museum.

Our firm is honored to have played a role in such a momentous repatriation. For more information about the case, please read one of our prior blog posts.

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Feb 22, 2018 |

Photo: Courtesy of University of Chicago

After a legal battle spanning over a decade, the fate of the Persepolis Collection at the University of Chicago has been determined. In a unanimous decision, the United States Supreme Court affirmed a decision by the federal appeals court in Chicago, ruling in favor of Iran. In an opinion written by Justice Sotomayor, the court writes that the plaintiffs cannot collect on a judgment against Iran by transferring ownership of antiquities.

This judgment stems from a case in which victims of a terror attack in Israel sued Iran and received a $71.5 million judgment against the Middle Eastern nation. Iran did not pay the judgment, and so the plaintiffs attempted to seize assets located in the US under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). The items they attempted to seize include the Persepolis Collection, a collection of 30,000 thousand clay tablets, many with Elamite inscriptions, loaned from Iran to the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute in 1937. The rare and historically priceless artifacts were excavated by the university’s archeologists in the 1930s in the ancient city of Persepolis. The finds were then given as a long-term loan to the Oriental Institute for cataloging, researching, and translating.

The victims argued that the objects could be seized under the FSIA (the same law used to restitute Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, known as “The Woman in Gold,” to Maria Altmann). The FSIA grants immunity to foreign states, except for nations (like Iran) designated as state sponsors of terrorism. In addition, the FSIA also exempts certain foreign-owned property in commercial use in the US. In this case, the lower court found that the FSIA exemptions cover property used by the foreign state, but do not include property used by a third party, like the university.

In finding that an exception to the FSIA does not apply, the victims will be unable to seize these objects. A representative from the University of Chicago, Marielle Sainvilus, stated, “The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago is committed to preserving and protecting a collection of Persian artifacts on loan from the Iranian government, which are among the region’s most important historical documents…These ancient artifacts, along with the Oriental Institute’s own Persian collection, have unique historical and cultural value. Today’s ruling reaffirms the University’s continuing efforts to preserve and protect this cultural heritage.”

In 2006, the then-director of the Oriental Institute Gil Stein described his disbelief, “It’s a bizarre, almost surreal kind of thing… You’d have to imagine how we would feel if we loaned the Liberty Bell to Russia and a Russian court put it up for auction,” Stein said.

The significance of objects from Persepolis cannot be understated. Persepolis is considered by UNESCO to have “outstanding universal value.” UNESCO describes Persepolis as “magnificent ruins…among the world’s greatest archaeological sites… among the archaeological sites which have no equivalent and which bear unique witness to a most ancient civilization.”

by Amineddoleh & Associates LLC | Jul 7, 2017 |

Photo courtesy of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

The owners of Hobby Lobby, a devoutly Christian company, have been profiled during the past few years for their questionable acquisitions of historic artifacts and the lack of reputable provenance research related to those items. The problems related to their purchases were publicly aired years ago, with evidence that the company acquires looted items from the Middle East. However, earlier this year, Hobby Lobby came under government scrutiny, leading to a civil forfeiture of thousands of artifacts.

As an advocate for responsible acquisition practices, it was an honor to consult with the Eastern District of New York regarding national and international cultural heritage laws related to purchases made by Hobby Lobby. The substance of the consultation with the government is confidential, however the US Attorney’s Office has officially released some very interesting information about the case. The most distressing, and unusual, aspect of the case is the fact that Hobby Lobby actually consulted with a cultural heritage expert back in 2010. Not only did the company confer with an expert, but they chose one of the most well-respected heritage experts in the world, a woman who has devoted her career to the protection of heritage items, Prof. Patty Gerstenblith. Yet contrary to Gerstenblith’s advice, Hobby Lobby continued to acquire objects that she warned them against purchasing due to the high probability that the pieces were looted.

What is the purpose of consulting with an expert, if that expert’s advice is not followed? It isn’t simply willful ignorance, but it is willfully ignoring important information. Why were red flags disregarded? Hobby Lobby defended itself in their public statement, “The Company was new to the world of acquiring these items, and did not fully appreciate the complexities of the acquisitions process. This resulted in some regrettable mistakes. The Company imprudently relied on dealers and shippers who, in hindsight, did not understand the correct way to document and ship these items.” But that is not believable since the company had access to information from one of the world’s leading heritage experts.

Another troubling aspect of this case relates to the company’s misrepresentations related to the nature of the goods. Not only did Hobby Lobby lie about the origin of the objects on customs forms, but they also lied about the value of those pieces. Information about the value and origin of an object is “material.” 18 USC 542 deems it a crime to import goods into the US by means of false statements, while 18 USC 545 makes it a crime to smuggle objects into the US.

The circumstances in this case reveal a great deal about the greed and secrecy in the art and antiquities markets. And although the company has agreed to return the artifacts and pay a $3 million fine, the result can never reverse the negative effects from acquiring looted antiquities.

Please return to this blog in the coming weeks for an upcoming article about red flags in the art and antiquities collecting world and for information about the due diligence process for the acquisition of heritage items.

UPDATE: Leila’s piece for Artnet about some of the legal strategies behind the Hobby Lobby matter: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/why-hobby-lobby-verdict-1021247

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

MArTA is one of Italy’s national museums. It was founded in 1887, and is housed on the site of both the former Convent of Friars Alcantaran and a judicial prison. Although most architectural structures from the Greek era in Taranto did not stand the test of time, archaeological excavations have yielded a great number of objects from Magna Graecae. This is due to the fact that Taranto was an industrial center for Greek pottery during the 4th century BC. As such, MArTA’s collection is impressive, displaying one of the largest collections of artifacts from Magna Grecia. Besides its rich holdings, this museum is unforgettable because of the ways in which it fulfills its cultural and educational purpose. The museum is arranged and curated along an “exhibition trail” so as to present visitors with a timeline of the city’s history. The displays move through time from the city’s prehistoric era to its Greek and Roman past and its medieval and modern history, in addition to integrating objects from outside Taranto that exemplify its location as a center of trade (including an exquisite statue of Thoth, the Egyptian god of scribes and writing). Toward the end of the trail, visitors are also confronted with information about the modern-day looting of artifacts and the work done to protect the city’s cultural heritage (more on that below).

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and

One of the more sensational stories is that the mummy board was on the SS Titanic in 1912 and